calsfoundation@cals.org

Law

Law develops out of the customs practiced by groups of people. In Arkansas, as in other places, the law has evolved over time with different cultures and interest groups within them. In the early eighteenth century, French colonizers replaced the familial and village-wide chiefdom systems of law developed by the natives with legal rules and regulations developed in France. These new rules appeared more sophisticated and complex than those developed by small groups of native hunter-gatherers. However, in many respects, they reflected a similar hierarchical structure with a hereditary ruler at the top.

Given the geographical distance from which these laws were applied, they had to be adapted to fit the circumstances of frontier living. As had the natives, local communities of settlers developed dispute mechanisms that provided more immediate resolutions than were available from territorial governors or courts.

When France sold its territory in North America to the United States in 1803, the land became subject to laws developed by the U.S. Congress and territorial and (later) state legislatures. Lesser law comes from county and city governments and applies to smaller groups of people and geographic entities. The framework on which all current laws are based came from the English common law (itself consisting of rules not too different from those developed by the native peoples), which provided for self-rule through representational bodies whose members were selected by local residents. As the country and the population grew, lawmaking became more complex, although its form remains recognizable. For over 200 years, the law-making systems adopted by the United States have worked well. New experiences and shifting attitudes about life affect the content of law, changing it constantly.

Pre-European Exploration through Louisiana Purchase

During the period from AD 900 to1541, agricultural economies flourished in the land that would become Arkansas. Bands of native peoples lived in numerous small communities governed by multi-member councils and participated in a regional commerce. Conduct and dispute resolution were handled by the community through the cooperative councils. As some communities prospered over others, individual leaders began to replace the cooperative councils. These leaders developed a hierarchical structure of governance.

These bands of native peoples, including the Quapaw, Osage, and Caddo, developed customs of conduct and penalties for the breach of custom. For example, Quapaw society was organized in terms of inherited status and relationships gained through marriage. Each village was ruled by a hereditary chief determined through the male line. He was assisted in village governance and war by various councils. The Caddo’s political organization was similar but included a priest with authority in both civil and religious affairs whose power extended across several allied communities. When Hernando de Soto’s Spanish expedition explored the land and fought with tribes resident in the area during the sixteenth century, its members established no law for the area.

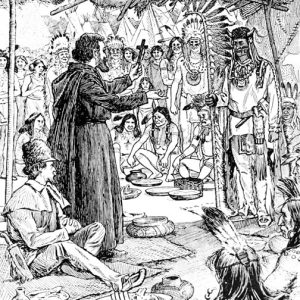

Nearly a century later, in July 1673, French explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet attempted to create a trade relationship with the Quapaw, but attacks from other tribes caused them to retreat north. About ten years later, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, along with Henry de Tonti and their soldiers, arrived among the Quapaw villages near the mouth of the Arkansas River at the Mississippi River and took formal possession of Arkansas for the king of France. In exchange, the French pledged on behalf of their king to protect the natives from their enemies.

De Tonti established and settled Arkansas Post (Arkansas County) in 1686, which served as a trading post and an intermediate station between French settlements in Illinois and on the Gulf of Mexico. Other than establishing rules of trade, the French probably had little impact on the native laws that operated among the Quapaw and other tribes. Lack of trade and a shortage of supplies caused the few citizens who settled the post to withdraw. By 1699, there was no trace of the French at Arkansas Post.

The land claimed for the French king by La Salle and de Tonti was considered part of the colony of Louisiana and included the present states of Alabama (western part), Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana (eastern part), Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Tennessee. The Louisiana Colony was divided into nine districts; Arkansas was one of them. In 1712, the colony adopted the “Coutume,” a set of French legal codes, which provided for governance by a Superior Council consisting of seven people: a lieutenant general, the governor of Louisiana, a first councilor of the king, two other councilors, the attorney general, and a clerk. This body had original and exclusive jurisdiction to rule on civil and criminal disputes arising anywhere in the colony.

In 1721, John Law, a Scottish banker residing in Paris, secured a monopoly on Louisiana trade and was granted land and a charter by the king of France. The charter allowed Law to appoint his own Superior Council, to name governors and military commanders, and to appoint and remove judges. Law recruited colonists and settled at the site of de Tonti’s abandoned trading post. A few years later, lower courts were created in various regions of the colony to apply law in places too far from the Superior Council for cases to be heard easily. These sessions were divided between civil and criminal matters and were presided over by appointed judges. The Superior Council heard all appeals.

Spain briefly obtained control over the Louisiana Colony area between 1762 and 1800. However, Spanish law had little effect during that thirty-eight-year period and none thereafter, when the French regained control. As the century passed, Arkansas Post became the economic and social center for a population of approximately 500 whites of French descent and an unknown number of Native Americans.

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase ended French possession and legal control over the territory that would become Arkansas. Over the next thirty years, Arkansas came under the control of various federal government structures. Initially, it was included in a large part of the purchase as the District of Louisiana and placed temporarily under the control of the governor and judges of the pre-existing Indiana Territory of the United States (established in 1800).

The Constitutional Convention of 1787 developed a legal template for the development of law in land claimed by the fledgling United States and into which the country intended to expand. The Northwest Ordinance providing for freedom of religion, right to trial by jury, and public education, as well as banning slavery, was administered by territorial officers appointed by the Congress. The ordinance worked similarly to a constitution and provided for limited self-rule through a territorial legislature. Once a territory’s population reached 60,000, it was eligible to petition Congress for admission to the Union as a state.

In 1806, the District of Arkansas was organized from the southern portion of the Louisiana Territory. A Court of Common Pleas was established for the district, which convened at Arkansas Post in December 1808. Divided into criminal and civil divisions, the courts were presided over by non-lawyer judges. A Superior Court, consisting of three judges, heard appeals and acted as the highest court in the District of Arkansas. License to practice law in the territorial courts could be granted by any two judges of the Superior Court. Applicants had to be at least twenty years old, of honest demeanor, and licensed to practice in either the U.S. Federal or District Courts located in their state of residence. A written certification attesting to these facts by the federal court was required.

In 1812, the Missouri Territory was created, and Arkansas became one of its counties. The creation of Arkansas County prompted the reorganization of a Court of Common Pleas in September 1814. It was renamed the General Court of Arkansas, and George Bullitt, the first lawyer-judge, replaced several local judges. The General Court met twice a year, enforcing laws created by Congress. Over the next five years, Arkansas County citizens began working to organize an independent territorial government. In 1819, Arkansas County was renamed the Arkansas Territory by Congress.

President James Monroe appointed a new territorial government, which held its first meeting as a territorial legislature to establish a foundation for the territory’s laws and governmental system in 1819. General laws of operation were adopted from those of the Missouri Territory, and two judicial circuits and other government offices were created.

At this point, Arkansas began to look like the modern state. In November 1819, an election was held to choose a delegate to the U.S. Congress, five members of the Legislative Council, and nine members of the lower house for the Arkansas Territory. The Superior Court was reorganized by the Arkansas Territorial government and assembled in January 1820 at Arkansas Post. The 1820 census documented a population of 14,273 people.

The first elected Arkansas territorial legislature met in February 1820, soon after the new governor arrived at Arkansas Post. The first session passed regulations for collecting taxes, created two new counties, and elected a public printer. The second session passed several acts that created additional counties and methods for census data collection and ordered the capital to be moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County). When the capitol was moved to Little Rock, the court followed. In 1821, two additional judges were appointed by the U.S. Senate.

The Arkansas Territory now had a court system that would look familiar to modern-day citizens. Each county had courts presided over by justices of the peace, with appeals handled by a county circuit court or court of common pleas. Three circuit court judges traveled around the territory, hearing cases in several different counties. Decedents’ estates were handled by separate probate courts. Appeals from the circuit or probate courts were heard by the Superior Court, which was the court of highest jurisdiction in the territory. The three circuit court judges sat as a panel for the Superior Court. In 1828, Congress added a fourth judge.

For a period, these courts operated primarily for white settlers, while Indian tribes, such as the Western Cherokee and the Osage, maintained separate governments and laws applicable to their own people. Indians became subject to the white courts only when they had interaction with white settlers. “Manifest destiny” was at work, however, and a series of treaties instigated by the federal government led to the removal of the Indian tribes from Arkansas to the Indian Territory to the west in 1828.

Early Statehood

Due to its rapid population growth, Arkansas quickly met the eligibility requirement for statehood, with 52,240 citizens. Consequently, in January 1836, Arkansas residents held a constitutional convention for the purpose of forming a constitution and state government. Since the number of delegates depended on total population, disputes arose in various regions of the state concerning who would be counted. In the end, only white men represented Arkansas’s population. Eight delegates were elected from the southeast and northwest geographic areas, and one delegate was elected from the middle of the state. After nearly four weeks in session, the delegates drafted Arkansas’s first state constitution, which closely resembled the U.S. Constitution, except that it prohibited enactment of emancipation laws without the permission of slaveholders. With constitution in hand, Arkansas Territory petitioned for admission to the Union. Congress ratified the proposed constitution on June 15, 1836, and Arkansas was admitted as the twenty-fifth state by President Andrew Jackson.

Voting in the new state was limited to any free, white, adult male. There were no property qualifications for voting or for holding office, and poll taxes were prohibited. In the first state election, voters elected the first governor, James S. Conway, and a U.S. representative, Archibald Yell. The old territorial legislature remained intact for the purpose of choosing the rest of Arkansas’s governmental officials. Ambrose Sevier and William Fulton were elected U.S. senators, and Benjamin Johnson became the first federal district judge for Arkansas. The territorial court system was replaced by a dual set of state and federal court systems.

The Arkansas Constitution vested the judicial power of the state “in one Supreme Court, in Circuit Courts, in County Courts and in Justices of the Peace.” The Supreme Court consisted of three judges, including a chief justice, and had only appellate jurisdiction. Statehood marked another period of rapid growth for Arkansas. By 1850, there was political stability and growth in a population of nearly 210,000 people, of whom 47,000 were slaves.

The Whig and Democratic political parties had dominated Arkansas politics during the territorial period. The Whig Party represented the wealthier, educated population in Arkansas (merchants and slaveholding planters) and was committed to economic growth and conservative social behavior. The Democratic Party appealed to small farmers and working men throughout the state. Shifts in political dominance led to shifts in the types of laws passed by the legislature. This self-interest was balanced by the state constitution, which promulgated certain basic principles of governance and could be changed only by the votes of a super-majority of the population. The courts, too, slowly shifted in position as they responded to changes in law and the judges were appointed by different political parties. This shift is seen clearly with regard to the treatment of African Americans during the slavery and Reconstruction periods.

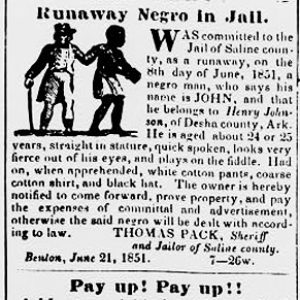

Slavery had become essential to Arkansas’s economic growth, which depended on cotton. In 1860, the state produced 150,000,000 pounds of the crop. Slavery became critical in the political sense, as well, particularly as new lands became available for settlement and their status as slave or free states became an issue in Congress. Passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 required every state to aid in the recapture of runaway slaves. As a slave state, Arkansas became concerned about the immigration of freedmen (ex-slaves) to the state. While their labor was welcome in some areas, there was no extraordinary legal control over them. As the agitation over slavery increased on the national scene, the Arkansas legislature attempted to resolve its problem by passing a law, Act 151 of 1859, ordering all freedmen to leave the state or risk being enslaved. Arkansas’s free black population dropped from 682 in 1858 to 144 in 1860.

Civil War through Reconstruction

Despite the Compromise of 1850, which attempted to maintain a balance in the admission of slave and non-slave states to the Union, slavery continued to be a divisive issue for the United States. When Abraham Lincoln, who opposed slavery, was elected president in November 1860, seven Southern states declared secession from the Union, creating the Confederate States of America (CSA) in February 1861. In Arkansas, although there were efforts to push the state into secession, the movement did not progress until voters approved the Secession Convention in February 1861 to consider the question. Delegates convened in March.

Initially, Union sympathizers had the strongest presence, resulting in a vote to remain with the Union. On April 12, however, Confederate president Jefferson Davis began the Civil War by giving orders to fire on the Union forces at Fort Sumter, South Carolina. When President Lincoln called for 75,000 men, including 780 men from Arkansas, to counter the rebellion, Governor Henry Massie Rector, a Confederate sympathizer, refused to provide troops. Convinced that the states bordering the Confederacy would soon secede, David Walker, an influential lawyer from Fayetteville (Washington County) and a prominent Whig, called for the reassembly of the convention. The second session of the Secession Convention resulted in a 69–1 vote to join the Confederacy. Arkansas was one of the last states to leave the Union.

Along with its secession vote, the convention approved a new state constitution, which replaced references to the United States with references to the Confederacy. The 1861 Constitution also removed a judicial provision requiring jury trials for slaves accused of crimes, made emancipation illegal, reduced the governor’s term from four to two years, and created a military board that was granted the power of governor during the war.

Despite the overwhelming vote to secede, Union sympathizers continued to resort to pre-secession judges, and the court system during the war was confusing. The Arkansas legislature also continued to meet despite the military board’s existence, also creating some confusion in lawmaking. After four years, on June 2, 1865, the war ended, and Confederate forces formally surrendered.

During the war, Arkansans’ loyalties were divided between the Confederacy and the Union. Neither side governed much beyond their army camps and the immediately surrounding land, which made law enforcement dependent on local sheriffs and citizens. Thus, enforcement was inconsistent throughout the state. The Union army took control of northwest Arkansas in the beginning stages of the war. By 1863, Union forces occupied Little Rock, in the center of the state, and the Confederate government was forced to move its capital to the town of Washington (Hempstead County). Although the Union forces did not control the entire state throughout the war, toward its end they began to form a new state government that conformed to guidelines set by President Lincoln, anticipating the Confederates’ defeat.

A need for law and order permeated the Reconstruction period as released soldiers roamed the land, heading home or trying to find a home. President Lincoln proposed a lenient policy that would pardon former Confederate states and allow them to rejoin the Union under certain conditions. Some Arkansans attempted to comply by adopting a new Arkansas Constitution in 1864 that abolished slavery. Although the proposed constitution was ratified by a public vote of 12,177 to 226, the Democratic Arkansas legislature rebelled against the president’s conditions. It refused to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which required due process and equal protection rights for former slaves. Instead, it enacted statutes regulating the behavior of the freedmen. As a result, Arkansas’s three congressional representatives and two U.S. senators were denied their seats and any representative capacity in Congress.

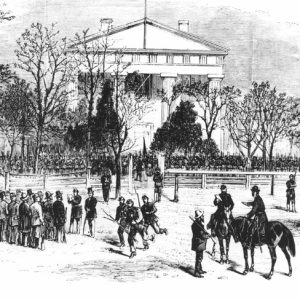

In March 1867, Congress passed the first of three Reconstruction Acts, dividing the former Confederate states into five military districts controlled by federal officers and requiring that new state constitutions provide for universal male suffrage. Arkansas and Mississippi made up the fourth military district. The Acts gave plenary powers to the district commander and substituted military tribunals for state courts. Men who had fought for the Confederacy were disfranchised until they swore an oath to support the United States.

Powell Clayton, a former Union officer, established the Republican Party in Arkansas in the same year. To consolidate its power, the party reached out to black citizens by promoting programs that would protect their civil and political rights. Almost 20,000 black voters were registered, most as members of the Republican Party. The November 1867 election ballot contained a referendum on a new constitutional convention. Some voters boycotted the election; others could not vote because they refused to take the oath. The referendum passed with the support of black voters. Seventy-five delegates were elected, eight of them black.

A constitutional convention assembled in Little Rock in January 1868. Among its many provisions were clauses giving black citizens the right to vote, serve on juries, hold office, and serve in the militia. The constitution was ratified in March, and on June 22, 1868, Arkansas was readmitted to the Union.

Powell Clayton, governor between 1868 and 1871, used the power granted in the constitution to strengthen the Republican Party’s position by providing new government services, such as police protection. A Republican legislature passed state civil rights acts that imposed severe penalties for discrimination against black citizens in voting, public transportation, and the use of facilities. Although resisted by Democrats, the Republicans were able to carry out an agenda that called for attracting immigrants to the state and expanding public education. The court system benefited by the adoption of the Code of Practice in Civil and Criminal Cases, which ended the old common law pleading system and allowed the courts to operate more efficiently.

Support for the Democratic Party grew as disfranchised voters regained their rights. The Republican Party lost a significant number of legislative seats in the 1870 elections. Election fraud was rampant on both sides during this period. A contested outcome in the 1872 election between Republicans Elisha Baxter and Joseph Brooks led to pitched battles in the street and was known as the Brooks-Baxter War. It ended only when President Ulysses S. Grant issued a proclamation recognizing Baxter as governor. Baxter worked to re-enfranchise white voters disenfranchised by the Reconstruction Acts. This was the beginning of the end of Reconstruction in Arkansas, as new laws began to restrict black civil rights.

The Post–Civil War Rise of Discrimination and Jim Crow

In 1874, with the Democratic Party now ascendant, citizens voted in favor of another constitutional convention that focused on again limiting the powers of the governor, restoring authority to county and municipal government, and introducing a county-based system for determining the number of representatives for most elective offices. County courts, consisting of an elected judge and an elected justice of the peace, had exclusive jurisdiction in local matters. These justices also had original jurisdiction in contract disputes, suits to recover personal property, and misdemeanor cases. They had concurrent jurisdiction with the circuit courts in other contract matters.

Because of this emphasis on local control, the state’s economy never recovered fully from the depredations of the war. The policies reflected the interest of the wealthy in low taxes and property assessments, resulting in limited operating funds for state government. In an effort to increase its economic security, the state adopted a convict lease system with the idea of financing a portion of the costs of the state’s government. Convicts were required to work for private industry, which paid compensation to the state for their labor. This was possible because of a growth in the prison population due to excessive punishments, the incarceration of children and the mentally insane, and the enforcement of agricultural laws that discriminated against African Americans, who made up two-thirds of the prison population. Application of the law weighed heavily on the poor and black.

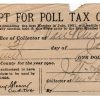

Between 1876 and 1892, interracial tension grew. The federal government withdrew its attention from the plight of former slaves, and discriminatory laws began to emerge in Arkansas. The Separate Coach Law of 1891, which segregated public transportation, was the first of these laws. Next came a reform of election laws, ostensibly to eliminate fraud, which resulted in the disfranchisement of poor white and black citizens alike. African Americans were prohibited from joining the Democratic Party, which developed total control over candidates and elections.

Slowly, Arkansas began to experience economic growth under the Democrats. The government worked to attract private investment capital to the state for railroad construction and to promote growth in lumbering, factories, and mining industries. A population expansion also created an increasingly diverse ethnic community and a developing class system. A growing population of professionals in Arkansas supported a more active and progressive state government. One result was expansion of the state’s regulatory functions, creating licensing requirements for individual occupations, regulating educational standards, ensuring healthcare to citizens, and a variety of other issues.

Although unable to vote, middle-class Arkansas women organized for governmental reform in the areas of women’s property rights and educational opportunity, support for children, and social regulation of alcohol and gambling. The Arkansas legislature granted the right to vote in the Democratic primary to women in 1917, with full voting rights coming with final ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920.

All this movement and change affected the law to which Arkansans were subject. Railroads brought communities closer together and led to interdependence between them. The state was no longer a frontier, where law primarily depended on local community custom for support. The state government became an important and cohesive force for the first time.

Prosperity did not last. Arkansas was hit hard by the Depression that began in the 1920s. The state’s farming and manufacturing industries were devastated, leading to social instability. The federal government now became an important regulating force as it provided aid to the state in the form of national welfare programs and New Deal legislation. This help came with conditions that grated against some sensibilities. In the mid-1940s, Governor Homer Adkins reacted against the growing strength and influence of the federal government in state and local affairs and urged enactment of laws limiting federal power.

Black Arkansans suffered the most from the Depression. Not only were they confined by segregation, but they also had to endure discrimination in the state and federal relief programs. As a result, education and healthcare suffered in black communities. In Robinson v. Holman (1930), the state Supreme Court rejected the efforts of a black political organization, the Arkansas Negro Democratic Association headed by Dr. John Marshall Robinson, to vote in the Democratic primary (from which black voters were barred) and to exert influence over elections.

Legal Movement toward Equality in the Modern Era

Robinson’s suit, despite its failure, was part of a growing movement among black Arkansans for more equal treatment under the law that mirrored a national effort spearheaded by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). After several unsuccessful attempts beginning in 1901, prominent black attorney Scipio A. Jones finally prevailed with the state Supreme Court in Bone v. State (1939), arguing that excluding black citizens from state court juries violated the constitutional rights of defendants, leading the court to overturn the conviction of two men charged with murder.

In Morris v. Williams (1945), Jones and lawyers with the NAACP obtained court rulings that the Little Rock School District discriminated against black public school teachers by paying them at lower levels than white teachers. In other action, Robinson’s 1930 suit was vindicated when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Smith v. Allwright (1944) that the Democratic Party’s practice of limiting its primaries to white voters was unconstitutional, although it was not until the early 1950s that the practice was ended in Arkansas.

Specific events can cause changes in the law and its application to citizens. The rise of workers’ unions seeking better wages and conditions in the 1930s and 1940s led to an Anti-Violence Bill, ostensibly against communist and un-American activity, that negatively affected the rights of working people in favor of employers. Patriotic fervor during World War II led to the misdemeanor conviction, in Johnson v. State (1942), of a man named Joe Johnson for exhibiting “contempt” concerning the American flag. The conscientious objector position taken by some citizens, including members of the Jehovah’s Witness religion, led to prosecution for sedition and disaffection.

The mid-1950s saw the rise in concern about the suppression of civil rights, partly due to the efforts of the NAACP. Challenges to restrictions on these rights led the federal courts to make decisions enforcing application of those laws in the country. For example, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954), overruled the “separate but equal” doctrine established by an earlier Supreme Court and required the integration of public schools. Arkansas’s governor, Orval Faubus, and the state legislature fought implementation of school integration all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, in Cooper v. Aaron (1958), arguing that state sovereignty made the decision unconstitutional.

The civil rights movement, with the help of federal acts and judicial rulings, expanded beyond the black community to include the rights of other groups—women, the handicapped, gays and lesbians, and students. These led, and continue to lead, to social transformation and changes in the law of Arkansas. For example, the state initiated a child abuse and neglect prevention board, passed a law mandating that African-American history be incorporated in the public school curriculum, and defeated a bill that would have banned gay people from becoming foster parents.

After a period of relative liberalization, federal and state law have swung toward a more conservative stance, as religious groups and others reacted to changes in the law they did not support. Some examples of the swing are the passage of a marriage amendment to the Arkansas constitution, defining marriage as between one man and one woman, and opposition to proposed regularization procedures for undocumented migrants, hate crime bills, gun control laws, and a state-sponsored lottery.

As these examples demonstrate, Arkansas law constantly evolves as society changes in response to the inflow of new people and ideas and the increased exposure of its citizens to the world outside Arkansas. Shifts in public opinion are likely to occur with more frequency as the speed and availability of communication increases. The creation of laws that provide for regulation and operation of the economy, and of lives, will continue, changing along the way.

For additional information:

Arkansas Judiciary Reporter of Decisions. https://www.arcourts.gov/courts/supreme-court/reporter (accessed August 19, 2023).

Arnold, Morris S. “The Arkansas Colonial Legal System, 1686–1766.” UALR Law Review 6 (1984): 391–423.

———. Unequal Laws Unto A Savage Race: European Legal Traditions In Arkansas, 1686–1836. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1985.

Bolton, Charles S. Arkansas Becomes a State. Little Rock: Center for Arkansas Studies, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 1985.

Donovan, Timothy P., Willard B. Gatewood Jr., and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Foster, Lynn. “Courts and Lawyers on the Arkansas Frontier.” UALR Law Review 26 (Spring 2004): 543–572.

Goss, Kay C. The Arkansas Constitution: A Reference Guide. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1993.

Kirk, John A., Kathleen Burrell, Brittany Fugate, Christy Hendricks, Ellis Eugene Thompson, Michael White, Logan H. Yancey. “Criminal Justice in the Age of Segregation: The Arkansas Cases of Robert Bell and Grady Swain.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 81 (Spring 2022): 19–45.

Law & Justice Collection. Old State House Museum Online Collections. Law & Justice Collection (accessed August 19, 2023).

Ledbetter, Cal, Jr. “The Constitution of 1836: A New Perspective.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 41 (Autumn 1982): 215–252.

———. “The Constitution of 1868: Conqueror’s Constitution or Constitutional Continuity?” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 44 (Spring 1985): 16–41.

Ledbetter, Calvin R., Jr. “The Constitutional Convention of 1917–1918.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 24 (Spring 1975): 3–40.

———. “The Proposed Arkansas Constitution of 1980.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 60 (Spring 2001): 53–74.

Nunn, Walter. “The Constitutional Convention of 1874.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 27 (Autumn 1968): 177–204.

Ross, Frances Mitchell, ed. United States District Courts and Judges of Arkansas, 1835–1960. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2016.

Smith, Stephen A., ed. First Amendment Studies in Arkansas: The Richard S. Arnold Prize Essays. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2016.

Williams, C. Fred, ed. A Documentary History of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1984.

Willis, James F. “Arkansas’s Gun Regulation Laws: Suppressing the ‘Pistol Toter,’ 1838–1925.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 81 (Summer 2022): 103–126.

Judith Kilpatrick and Samantha Fields

University of Arkansas School of Law

Adverse Possession

Adverse Possession Amendment 44

Amendment 44 Amendments 19 and 20

Amendments 19 and 20 Arkansas Bar Association

Arkansas Bar Association Arkansas Cannon, Seizure of

Arkansas Cannon, Seizure of Arkansas Civil Rights Act of 1993

Arkansas Civil Rights Act of 1993 Arkansas Court of Appeals

Arkansas Court of Appeals Arkansas General Assembly

Arkansas General Assembly Bennett, Bruce

Bennett, Bruce Bonnie and Clyde

Bonnie and Clyde Bunn, Henry Gaston

Bunn, Henry Gaston Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Disability Issues

Disability Issues Election Fraud

Election Fraud Election Law of 1891

Election Law of 1891 Equal Rights Amendment (ERA)

Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) Fort Smith Sedition Trial of 1988

Fort Smith Sedition Trial of 1988 Hammond Packing Company v. Arkansas

Hammond Packing Company v. Arkansas Jim Crow Laws

Jim Crow Laws Jim DuPree v. Alma School District No. 30

Jim DuPree v. Alma School District No. 30 Kimbrough, Wilson Whitaker, Jr.

Kimbrough, Wilson Whitaker, Jr. Leflar, Robert Allen

Leflar, Robert Allen Mitchell v. United States

Mitchell v. United States Overton, William Ray

Overton, William Ray Prohibition

Prohibition Right to Work Law

Right to Work Law Rose Law Firm

Rose Law Firm Skipper v. Union Central Life Insurance Company

Skipper v. Union Central Life Insurance Company Slave Codes

Slave Codes Supreme Court of Arkansas

Supreme Court of Arkansas United States v. Waddell et al.

United States v. Waddell et al. University of Arkansas School of Law

University of Arkansas School of Law University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law

University of Arkansas at Little Rock William H. Bowen School of Law Voting and Voting Rights

Voting and Voting Rights Warren, Joyce Elise Williams

Warren, Joyce Elise Williams Women's Suffrage Movement

Women's Suffrage Movement Homer Adkins

Homer Adkins  Elisha Baxter

Elisha Baxter  Brooks-Baxter War

Brooks-Baxter War  Joseph Brooks

Joseph Brooks  Powell Clayton

Powell Clayton  James Conway

James Conway  Henri de Tonti

Henri de Tonti  Doran Trial Story

Doran Trial Story  Orval Faubus

Orval Faubus  William Fulton

William Fulton  Gay and Lesbian Movement Press Conference

Gay and Lesbian Movement Press Conference  Hempstead County Courthouse

Hempstead County Courthouse  Benjamin Johnson

Benjamin Johnson  Scipio Jones

Scipio Jones  Judicial Districts

Judicial Districts  René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle  Marquette-Joliet Expedition

Marquette-Joliet Expedition  Henry Rector

Henry Rector  Runaway Slave Article

Runaway Slave Article  Segregated Waiting Room

Segregated Waiting Room  Segregationist Rally

Segregationist Rally  Ambrose Sevier

Ambrose Sevier  David Walker

David Walker  Archibald Yell

Archibald Yell

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.