calsfoundation@cals.org

Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America (PFHUA)

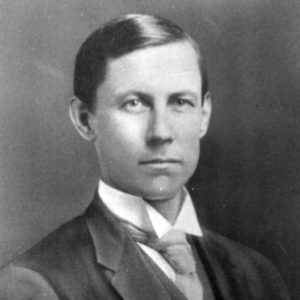

Robert L. Hill of Drew County, along with physician V. E. Powell, incorporated the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America (PFHUA) in Winchester (Drew County) in 1918. Hill, an African American, referred to himself as a “U.S. Detective” because he had taken a St. Louis, Missouri, correspondence course in detective training, but some people identified him as a farmer or farm hand. According to the articles of the constitution of the PFHUA, the group’s objective was “to advance the interests of the Negro, morally and intellectually, and to make him a better citizen and a better farmer.”

The organization had characteristics of a fraternal order, such as passwords, handshakes, and signs for members, and it also resembled a union. Members purchased shares for one dollar, resulting in a capital stock of $1,000 for the joint stock company of the PFHUA. This stock was designed to allow the organization to invest in real estate. An elected salaried deputy in charge of organizing clubs held office for six months. According to Hill, the history of the union began in 1865 in Washington DC, under an act of Congress. Then, it was known as the Colored Union Benevolent Association.

The PFHUA grew steadily during the spring of 1919 as sharecroppers and tenant farmers around Elaine (Phillips County) joined the order. Phillips County villages such as Ratio, Hoop Spur, Modoc, Old Town, Mellwood, and Ferguson were represented. The economic situation of the post–World War I Delta region of Arkansas explains the order’s growing membership. Black sharecroppers and tenants, some war veterans, sought to take advantage of the favorable economic conditions and sell the 1919 cotton crop for their own—not their landlords’—profit. For their part, planters wished to reverse the wartime gains of black laborers and reassert their control over labor and workers.

The PFHUA stood at the center of the Elaine Massacre of 1919. Members took preliminary steps toward economic independence by hiring Little Rock (Pulaski County) lawyer Ulysses S. Bratton to sue their landlords for their share of the large 1919 fall cotton crop. However, earlier nationwide strikes led planters in the area to believe that the organization represented a significant, and possibly violent, challenge to their economic and social hegemony. The violence began when black PFHUA guards exchanged gunshots with armed whites at a PFHUA meeting at a church in Hoop Spur on the night of September 30. The violence quickly escalated as white posses and federal troops scoured the region for several days, killing a number of African-American men, women, and children—some estimates put the number of those murdered in the hundreds.

Initially, 122 black men and women were indicted for charges such as murder and night riding as a result of a claim by the Committee of Seven (an investigating committee created by the county’s white power structure) that Hill manipulated PFHUA members into staging an insurrection. An investigation by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) characterized the violence as an extreme response by white landowners to black unionization. The “Elaine Twelve,” a dozen black prisoners who received the death sentence for their alleged role in killing several whites, were eventually released after Arkansas courts and the U.S. Supreme Court, in the landmark case of Moore v. Dempsey, found the rushed proceedings against them unsustainable.

In eastern Arkansas, it seems that the PFHUA dissolved quickly after the Elaine Massacre. The white residents, planters, and businessmen in the area heavily discouraged further black union activity, via intimidation and sometimes violence.

For additional information:

Cortner, Richard C. A Mob Intent of Death: The NAACP and the Arkansas Riot Cases. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1988.

Lancaster, Guy, ed. The Elaine Massacre and Arkansas: A Century of Atrocity and Resistance, 1819–1919. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

Stockley, Grif, Brian K. Mitchell, and Guy Lancaster. Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Massacre of 1919. Rev. ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Whayne, Jeannie M. “Low Villains and Wickedness in High Places: Race and Class in the Elaine Riots.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Autumn 1999): 285–313.

Woodruff, Nan Elizabeth. American Congo: The African American Freedom Struggle in the Delta. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003.

Jason McCollom

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Labor Movement

Labor Movement Ulysses S. Bratton

Ulysses S. Bratton  Robert L. Hill

Robert L. Hill

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.