calsfoundation@cals.org

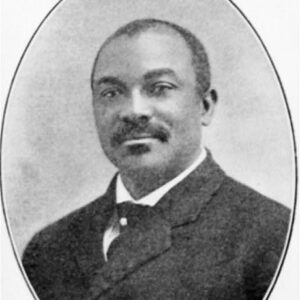

Joseph Albert Booker (1859–1926)

Joseph Albert Booker—noted editor, educator, and community leader—was for four decades a prominent leader in Arkansas racial relations and a pioneer in African American education in the state.

Joseph A. Booker was born into slavery on December 26, 1859, in Old Portland, east of modern Portland (Ashley County). He was the son of Albert and Mary (Punchardt) Booker, who were slaves on the large Bayou Bartholomew plantation of John P. Fisher. Booker’s mother died shortly after his birth. According to one source, when Booker was three, his father, a man with “some knowledge of books,” died when his slave master whipped him to death. His father’s crime was urging his fellow slaves to revolt by “teaching them to read.”

At the end of the Civil War, Booker, then a child, was placed in the care of his maternal grandmother, Emma Fisher, who nurtured him with “true motherly zeal.” Even at this early age, he showed a remarkable aptitude for learning. With the opening of public schools, Booker’s grandmother “saw that [he] was one of the first pupils enrolled.” Despite the difficulty Black Americans had at the time obtaining an education, the child “studied at every school within his reach” in Ashley County.

At the age of sixteen or seventeen, he became a teacher on the nearby Harris plantation, also in Ashley County. At about the same time, he began his life-long interest in religion and was licensed to preach as a Baptist minister. From 1878 until 1881, he attended Arkansas Agricultural, Mechanical, and Normal College, now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff (UAPB) in Jefferson County. Here, he came under the tutelage of Professor Joseph C. Corbin, who “created in him a thirst for deep and intricate learning.” In 1881, Booker moved to Nashville, Tennessee, to attend what would become Roger Williams University, enrolling in the “classic course.” He graduated from that institution with a bachelor’s degree in 1886.

Shortly afterward, Booker returned to his home in southern Arkansas and turned his attention to full-time preaching. He soon received an appointment as State Missionary for the Arkansas Negro Baptist Convention and the American Baptist Missionary Society and was ordained as a Baptist minister by the “No. 2” Baptist Church at Portland on August 22, 1886. Within the year, he was chosen as the first president of the newly established Arkansas Baptist College in Little Rock (Pulaski County), a position he would hold until his death. At the same time, he began a long tenure as editor of the state’s Black Baptist newspaper, the Baptist Vanguard, published in Little Rock. In June 1887, he married Mary Jane Caver. The couple had eight children, including Joseph Robert Booker, who would become a noted civil rights lawyer.

Booker undertook his new tasks with such spirit and determination that, before long, he became widely known for “his industry and culture” throughout the community. In 1891, he was one of the leaders in the Black community’s opposition to the “separate coach” law. Throughout his life, he was one of the state’s strongest advocates for Black citizens’ “self help” education. At the same time, he worked tirelessly to foster a “spirit of good will” within the Black community toward the white establishment. In furthering these goals, he worked with Booker T. Washington and often hosted him when he visited Little Rock. From 1911 to 1913, he served on the Little Rock “Colored Vice Commission,” which sought to clean up Little Rock’s notorious red light districts. In 1919, shortly after the outbreak of the Elaine Race Massacre in eastern Arkansas, Booker accepted an appointment by Governor Charles H. Brough to the Arkansas Commission on Race Relations. Although criticized by more militant Black leaders for his lack of activism, Booker used his position on the commission to promote “interracial justice” for all of the state’s citizens.

Early in September 1926, Booker, seemingly in good health, left Little Rock to attend the National Baptist Convention in Fort Worth, Texas. On the night of September 9, he was suddenly stricken with a heart attack and died within a few minutes. His body was returned to Little Rock, and he was buried in Haven of Rest Cemetery.

For additional information:

Dunaway, Louis Sharpe. What a Preacher saw Through a Keyhole in Arkansas. Little Rock: Parke-Harper Pub. Co., 1925.

Penn, I. Garland. The Afro-American Press and its Editors. New York: Arno Press, 1969.

Woods, Elias McSails. Blue Book of Little Rock and Argenta, Arkansas. Little Rock: Central Printing Co., 1907.

Russell P. Baker

Arkansas History Commission and State Archive

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Religion

Religion Joseph A. Booker

Joseph A. Booker  Joseph A. Booker

Joseph A. Booker  Mary Jane Booker

Mary Jane Booker

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.