calsfoundation@cals.org

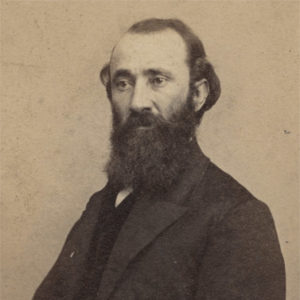

Edward W. Gantt (1829–1874)

Edward W. Gantt became one of southwestern Arkansas’s leading politicians in the Civil War era. He pushed for secession in 1860, led Confederate troops in 1861–1862, and then abruptly supported the Union from 1863 to 1865. He promoted radical social, economic, and political change during Reconstruction as he led the Freedmen’s Bureau and Radical Republicans in Arkansas.

Edward W. Gantt was born in 1829, the son of George Gantt, a teacher and Baptist preacher, and Mary Elizabeth Williams. He decided to become a lawyer and attended the 1850 Nashville Convention, which considered secession during the crisis over California statehood. Hoping to find opportunities in the booming Southwest, he moved to Washington (Hempstead County) in 1854.

The Sixth Judicial District elected Gantt prosecuting attorney in 1854 and reelected him in 1856 and 1858. He married a local wealthy planter’s daughter, Margaret Reid, in 1855; they had two sons and two daughters. By 1858, he had a voluminous library, three carriages, eight slaves valued at $7,000, and real estate assessed at $10,000.

Yearning for more power, Gantt sought election to Congress in 1860 from the Second Congressional District. Opposing “The Family,” the oligarchy that had controlled much of Arkansas politics since 1833, insurgent Thomas Hindman supported him, and he won election to the House of Representatives in August 1860.

But 1860 presidential politics interfered. Gantt, Hindman, and others favored secession after the election of Abraham Lincoln. Focusing on the mountainous northern and western parts of the state where Unionists flourished, Gantt gave fiery secessionist speeches. Arkansas joined the Confederacy on May 6, 1861.

Although Gantt was not given a commission as major general as he requested, the men of the Twelfth Arkansas Infantry Regiment, mustering around Arkadelphia (Clark County), elected him as their colonel. He procured arms for the soldiers and medicines when illnesses ravaged the camp. In late 1861, the regiment moved toward the Mississippi River, where they tried to maintain Confederate control of the river between St. Louis, Missouri, and Memphis, Tennessee.

Gantt’s first involvement in action occurred in November 1861 during the Battle of Belmont, an inconclusive foray against General Ulysses S. Grant. During the battle, his regiment was held in reserve opposite the river at Columbus, Kentucky; however, Gantt was wounded in an exchange of fire between Confederate batteries and Union gunboats supporting Grant’s attack. In December 1861, Gantt supervised another regiment and moved southward toward Island Number 10 in the Mississippi River near New Madrid, Missouri. Throughout the icy winter, his men built breastworks and prepared to repel the Northern invaders.

Beginning in March 1862, Gantt’s men clung on to their defensive positions as Yankee penetration failed. But during a fierce night-time thunderstorm on April 1, 1862, Colonel George Roberts and fifty hand-picked men surprised Confederates and disabled several guns on the island, allowing Union gunboats to go downstream and cut off the island. In response to this situation, Gantt, along with 7,000 other Rebel soldiers and three generals, officially surrendered on April 8, 1862. He and other Southern officers were imprisoned at Fort Warren, Massachusetts, where he stayed until his negotiated release in August 1862.

Returning to his home in Washington, Gantt awaited re-commissioning in the Confederate army. Whether it was because of his fondness for alcohol, his tendency to flirt with officers’ wives, or his role in the surrender at Island Number 10, Confederate leaders refused to offer him another leadership position. Brooding until the summer of 1863, Gantt finally believed the Confederacy offered him no hope of military or political glory. In June 1863, he slipped to Vicksburg, Mississippi, and surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant.

Grant recognized that Gantt and other Southern turncoats could boost Northern morale. Meeting with President Abraham Lincoln in July 1863, Gantt swore allegiance to the North and promised to help end the war and restore the Confederate states to the Union. Throughout 1863 and 1864, he toured the North and urged war-weary Northerners to persevere. He and other Arkansas Unionists hammered out the details with Lincoln for allowing Arkansas to return to the Union through the Ten Percent Plan, Abraham Lincoln’s lenient plan to let seceding Southern states back in the Union when ten percent of the eligible voters in 1860 swore allegiance to the Constitution and abolished slavery.

As the war ended in April 1865, Gantt actively pushed for black freedom as the general superintendent of the Southwest District of Arkansas of the Freedmen’s Bureau, a federal agency created at the end of the war to help former slaves become genuinely free. He encouraged African Americans to work hard, supervised contracts between slaves and planters, supervised marriage ceremonies between former slaves, adjudicated disputes between blacks and whites, provided healthcare formerly provided by planters, facilitated the establishment of black churches and schools, and encouraged black political activism.

Gantt moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1866 and became prosecuting attorney in 1868, pushing Radical Reconstruction. Throughout 1867 and 1868, he supported Union Clubs, which backed Republican Ulysses S. Grant for the presidency in 1868. Opposed by many unreconstructed Confederates, Gantt faced constant death threats and at times carried seven guns. Two Little Rock businessmen who opposed his radicalism severely beat him in 1869.

The strain and violence of Radical Reconstruction forced him to resign as prosecutor in 1870. Needing a respite, he turned his attention to codifying the laws of Arkansas in 1873.

On June 10, 1874, Gantt suffered a heart attack and died. He is buried in Tulip (Dallas County).

For additional information:

DeBlack, Thomas. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Finley, Randy. From Slavery to Uncertain Freedom: The Freedmen’s Bureau in Arkansas, 1865–1869. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1996.

———. “‘This Dreadful Whirlpool’ of Civil War: Edward W. Gantt and the Quest for Distinction.” In The Southern Elite and Social Change: Essays in Honor of Willard B. Gatewood, Jr., edited by Randy Finley and Thomas A. DeBlack. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2002.

Moneyhon, Carl. The Impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction in Arkansas: Persistence in the Midst of Ruin. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994.

Randy Finley

Georgia Perimeter College

Edward Gantt

Edward Gantt

The 12th was serving in the Garrison of Columbus, Kentucky, directly across the river from Belmont, but they were not part of the relief force dispatched under Brig. Gen. Pillow. The only Arkansas unit engaged at Belmont was the 13th Arkansas under Colonel Tappan. Gantt was apparently almost killed in an exchange of fire between the Confederate batteries at Columbus and the Union gunboats supporting Grant’s attack at Belmont, but the men of the 12th Arkansas were never directly engaged. Sources: Hughes, Nathaniel Cheairs. The Battle of Belmont: Grant Strikes South (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press), 1991.; Feis, William B. “Battle of Belmont.” In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000).