calsfoundation@cals.org

Natalie Smith Henry (1907–1992)

An artist of national significance, Natalie Smith Henry made her reputation as an easel painter and muralist during the Depression era. At the height of her career in 1939, the U.S. Treasury Department commissioned her to paint post office art in Springdale (Washington and Benton counties). In later years, Henry combined her interest in art with her business acumen, managing the Art Institute of Chicago School Store for twenty-three years.

Natalie Henry was born on January 4, 1907, in Malvern (Hot Spring County). She was the eldest of five children born to Samuel Ewell Henry, circuit clerk and Hot Spring County judge, and homemaker Natalie Smith. After his wife died, Samuel Henry married Minerva Ann Harrison. They had two children.

Left motherless at age twelve, Henry channeled her grief into creative activity, first by building an elaborate tree house, and, at age fifteen, by enrolling in the Magazine and Book Illustration program through the International Correspondence Schools of Scranton, Pennsylvania. Noting Henry’s precocious artistic skills and optimistic outlook, her Malvern High School classmates voted her “most original and class giggler” upon graduation in 1925. Her passion for art, fueled by her love of life, was the defining force throughout her life.

In 1925–26, Henry attended Galloway College in Searcy (White County), one of the state’s largest and most prestigious women’s colleges. After moving to Chicago, Illinois, in 1928, she attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, the largest of its kind in the United States, where she studied painting and drawing from September 1929 to December 1932. Henry achieved the equivalent of a four-year art degree in 1937 by attending the Hubert Ropp School of Art in Chicago on a part-time basis. An astute businesswoman, Henry did recordkeeping for Ropp in exchange for tuition and worked part time as a typist from 1931 to 1942 at the Ryerson Library, housed in the Art Institute of Chicago.

Choosing not to marry, Henry struggled financially. Like many unmarried female artists of her era, she found it necessary to work part time in secretarial positions, but this compromise determined that she was neither a full-time artist nor a career businesswoman. That she was not a full-time artist also meant she was ineligible later to work for the federal Works Progress Administration (WPA).

Inspired by the premier collections at the Art Institute of Chicago, including the blockbuster “A Century of Progress” exhibitions held there in 1933 and 1934 as part of the Chicago World’s Fair, Henry sought recognition in the art world by exhibiting at the national level. In 1935, she exhibited Picnic at the prestigious Annual Exhibition of Artists of Chicago and Vicinity. In 1936, she exhibited Man with Shells at the International Water Color Exhibition, alongside works by notable European and American artists, including Kandinsky, Hopper, and Wood. Henry also exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1937, 1941, and 1944. In 1944, she joined the Chicago Society of Artists, the oldest continuous art association in the United States, and submitted works annually thereafter until 1987.

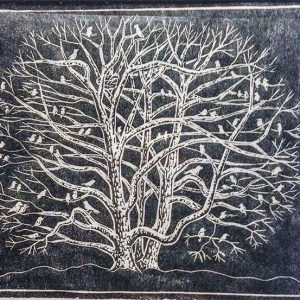

Like many American artists who received their training during the Depression era, Henry worked in the realist style, emphasizing firm contour lines, clearly described volumes, and recognizable narrative imagery. Over the course of her sixty-year career, she treated a wide range of themes using figural scenes, portraits, landscapes, and still life. In addition to oil and watercolor, Henry also worked in the medium of block printing. Instead of creating fine art prints, however, she applied her printmaking skills to more commercial applications. From 1948 to 1992, she supplemented her income by making woodblock designs for calendars published by the Chicago Society of Artists, as well as making block-printed greeting cards to sell to department stores in Chicago.

In 1939, Henry returned to Arkansas to create a mural for the Springdale post office, undoubtedly the most important painting of her career. The mural, titled “Local Industries,” was commissioned by the Treasury Department’s Section of Fine Arts, the U.S. government’s largest public art program ever. In May 1939, she traveled to Springdale to interview residents and collect data about the area. She concluded that a panoramic landscape, featuring poultry and fruit farmers, would be appropriate. (Tyson Foods and Welch Foods Inc. were in their infancies in Springdale.) When the mural was installed on November 14, 1940, the Springdale News praised the artist. At the end of the Depression and with World War II on the horizon, Henry’s idyllic image offered Arkansans a reassuring vision of peace and prosperity.

World War II caused Henry to think seriously about her financial future. In 1942–43, she worked for the Office of Price Administration–Rent Division, the federal agency established to prevent wartime inflation. Between 1943 and 1948, she worked full time in commercial art until she became manager of the Art Institute of Chicago School Store (1949–1972).

Henry left Chicago to retire in Malvern in 1985. She continued to exhibit her paintings in local exhibitions until 1991. She died in Malvern on February 20, 1992, and is buried in Oak Ridge/Shadowlawn Cemetery in Malvern. Henry’s works are in the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington DC, in the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History in Springdale, and in numerous private collections.

For additional information:

Arkansas Post Office Mural Project. University of Central Arkansas. https://uca.edu/postofficemurals/home/ (accessed March 20, 2021).

Gill, John Purifoy. Post Masters: Arkansas Post Office Art in the New Deal. Jonesboro: Arkansas State University Foundation, 2002.

Park, Marlene, and Gerald E. Markowitz. Democratic Vistas: Post Offices and Public Art in the New Deal. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1984.

Gayle M. Seymour

University of Central Arkansas

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment Business, Commerce, and Industry

Business, Commerce, and Industry Birds in Tree in the Winter by Natalie Henry

Birds in Tree in the Winter by Natalie Henry  Natalie Henry

Natalie Henry  Local Industries by Natalie Henry

Local Industries by Natalie Henry

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.