calsfoundation@cals.org

Southern Tenant Farmers' Union

The Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU) was a federation of tenant farmers formed in July 1934 in Poinsett County with the immediate aim of reforming the crop-sharing system of sharecropping and tenant farming. The facts that the STFU was integrated, that women played a critical role in its organization and administration, and that fundamentalist church rituals and regional folkways were basic to the union’s operation dramatically foreshadowed the post-war civil rights era.

A series of natural disasters in the late 1920s and early 1930s, plus the unique circumstances present in Poinsett County, led to the formation of the STFU. The Flood of 1927 revealed the desperate plight of the Delta cropper to the outside world, sparking the interest of unionists and the Socialist Party; in Poinsett County, there was some sympathy for socialist ideas among area merchants. The stock market collapse of 1929, coupled with the Drought of 1930–1931, totally destroyed farm income. The Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA), as part of a New Deal attempt to raise the price of cotton, paid planters to plow up a percentage of the crop their tenants had already planted. Fifty percent of this payment was meant for the tenant or cropper, but planters devised means to keep almost all of the money. With increasing incentives not to grow cotton, many planters evicted their tenants, leaving them homeless. Indeed, the event that set into motion the creation of the STFU was planter Hiram Norcross removing twenty-three families from his plantation in late spring 1934. At the Sunnyside School on the boundary of Norcross land in July 1934, a group of seven black and eleven white men agreed to form a union of tenants and sharecroppers. After some discussion, they decided that the union should be fully integrated, recognizing that they shared similar needs and economic situations. This was a stunning break with the past, though in some areas there would be separate black and white locals as the union expanded.

Another critical factor in the formation of the STFU was the organization of an active socialist local in Tyronza (Poinsett County) by H. L. Mitchell and H. Clay East. Mitchell ran a dry cleaning shop in Tyronza and was a former sharecropper from Halls, Tennessee. He became a socialist in Tennessee and later converted East to the cause. The two of them went to meetings in Memphis together, organized the local in Tyronza, and helped to organize the Tyronza Unemployment League in the spring of 1934. The Unemployment League was an attempt to force the local agencies of the AAA to provide jobs for desperate tenants or croppers. At the instigation of Norman Thomas, the leader of the Socialist Party in the United States, the two men participated in the formation of the STFU.

Many opponents of the STFU considered it to be a communist plot, and attacks from planters, both physical and verbal, was the norm at early meetings. Ward Rodgers, the STFU’s most effective white organizer, was arrested and jailed in Marked Tree (Poinsett County) in January 1935. As a result, Mitchell called Lucien Koch, the director of Commonwealth College in Polk County, and asked for help in founding locals. Commonwealth had the reputation of being a communist institution; given Mitchell and East’s hatred of communists, this appeal was a sign of real desperation.

Koch and Bob Reed, a Commonwealth student, attempted to stage a rally at Gilmore (Crittenden County). Held at New Prosperity, a black church, the rally opened with the STFU hymn, “We Shall Not Be Moved.” As soon as Koch was introduced, four armed white men broke in and ordered the African Americans to leave, telling them that they would be lynched if they were caught at another union gathering. Many union members were beaten and threatened with guns, and Reed and others were forcibly taken to the county seat for questioning. There, the authorities threatened their lives if they continued their activities and ordered them removed from the county. This typified the violence that often confronted the organizers from 1934 to 1936 in eastern Arkansas. The Commonwealth presence seemed to confirm the “Red” nature of the union. Norman Thomas urged the STFU leadership to send the Commoners home; they did so in March 1935. On March 15, 1935, about 500 members of the STFU gathered at Birdsong (Mississippi County) to hear a speech by Thomas, but as Thomas rose to speak, about forty angry armed planters, their riding bosses, and lawmen broke up the crowd and then threatened the life of Thomas. Mom members later that month attacked the home of STFU lawyer Cornelius Tyree Carpenter.

Organizational and general meetings of the union took the form of revivals, complete with rituals, union songs, skits, and rousing addresses. Many rituals were drawn from local custom and folkways or from secret societies (such as the Freemasons), which had long been a part of the Southern rural milieu. Since numerous rallies were held in churches and supported by preachers, an aura of religious fervor often permeated the occasions and added to the evangelical character of the movement. The fundamentalist, primarily Baptist, churches that cropper families attended were frequently the cutting edge for union organization and administration. This is especially true of the black churches. Women’s involvement in these churches often translated into a deep involvement in union activities.

The union continued to expand throughout 1935 and 1936. Violence was common, and Mitchell and East moved the STFU headquarters to Memphis in late 1935 to escape intimidation. Union leaders also sought protection from the Agricultural Adjustment Administration. Getting no help there, they then turned to people who had left the AAA because of its tendency to support planters rather than tenants. Gardner Jackson, one of these displaced AAAs, initiated a campaign among New Dealers in Washington to focus attention on the plight of the croppers. The La Folette Committee investigation of free speech and the rights of labor sprang, in great part, from Jackson’s campaign to halt the violence prompted by the establishment of the STFU, and the union soon garnered some financial support from outside the South.

The 1936 election campaign saw rising national sympathy for the sharecropper; indeed, Senate Majority Leader Joseph T. Robinson of Arkansas, a close friend of Delta planters, met with Mitchell, Jackson, and other STFU leaders during the Democratic National Convention in June. The senator agreed to support union positions in legislation and in the Democratic Party platform and helped persuade Arkansas governor Junius Futrell to clamp down on violence against sharecroppers. Futrell quickly appointed a commission to study the problems of tenancy. Much of the violence that had threatened the union ebbed, and the STFU moved into neighboring states. By 1938, it had more than 35,000 members, mostly in eastern Arkansas.

Few open attacks occurred after the election of 1936. Instead, the STFU’s problems came from within the union. Movements to join the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), rebellious withdrawals of support, and communist infiltration all posed new threats. After long and strident debate, the union joined the CIO in 1937, only to withdraw a year later. Mitchell, Kester, and others had opposed amalgamation with the CIO because of its well-publicized communist ties. During the CIO debacle, The Reverend E. B. (Britt) McKinney—preacher, black nationalist, and one of the union’s most effective organizers and motivators—decided that the STFU was just another device to exploit and suppress black people and started a movement to persuade African Americans to leave the STFU and cooperate with the CIO. At the same time, Claude Williams, the director of Commonwealth College and one of the STFU’s best troubleshooters, approved a plan to seize the union for the Communist Party. These attempts to change the STFU’s course were overwhelmingly voted down at the convention, and both McKinney and Williams were expelled from the union at its fifth annual convention at Cotton Plant (Woodruff County). McKinney was subsequently restored as a member, but he no longer had a leadership role.

Later that same year, furor over dues, STFU autonomy, and communism drove Mitchell and his followers out of the STFU, after which it began to fall apart. National attention gravitated to the threat of war, which, combined with the advent of the mechanical cotton picker, tractors, and the Great Migration, rendered the STFU increasingly irrelevant. It soon survived in name only. Mitchell returned to the shadow STFU in 1941 as executive secretary and served as president from 1944 to 1960. During this time, the union became the National Farm Labor Union and later the National Agricultural Worker’s Union and participated in some important court cases highlighting the plight of African Americans and union members, such as Edmondson Home and Improvement Company v. Harold E. Weaver and State of Arkansas v. Tee Davis. The STFU really died when Mitchell died in 1989.

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of the STFU was its pre–Civil Rights Era example of the effectiveness of racial integration to achieve common goals. The STFU’s use of well-known rituals, songs, speech patterns, and evangelism became a model for the southern civil rights movements to draw upon. Though these techniques had been used in varying forms throughout the nineteenth century to mobilize public opinion, the STFU’s religious fervor was new. This combination of evangelism, practicality, and purpose would provide an operational example for later civil rights and women’s movements, setting the stage for the next half of twentieth-century American life. The history of the union is preserved at the Southern Tenant Farmers Museum in Tyronza.

For additional information:

Auerbach, Jerold S. “Southern Tenant Farmers: Socialist Critics of the New Deal.” Labor History 7 (Winter 1966): 3–74.

Chandler, Erin. “Howard Kester’s Prophetic Agrarian Rhetoric: The Social Gospel Roots of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, 1934–1940.” Southern Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal of the South 28 (Spring–Summer 2021): 69–93.

Fraser, John. “Pragmatism and Protest: New Deal Cotton Reform and the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, 1933–1936.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 52 (August 2021): 83–96.

Grisham, Cindy. “When Hope Grows Weary: An Arkansas Delta Town in Place and Space.” PhD diss., Arkansas State University, 2012.

Grubbs, Donald H. Cry from the Cotton: The Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union and the New Deal. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1971.

Hawkins, Van. Plowing the New Ground: The Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union and Its Place in Delta History. Virginia Beach, VA: Donning Co. Publishers, 2007.

Honey, Michael K. Sharecropper’s Troubadour: John L. Handcox, the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, and the African American Song Tradition. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Kern, Jamie. “State v. Rodgers: The 1935 Anarchy Trial of Ward Rodgers in Poinsett County.” In First Amendment Studies in Arkansas: The Richard S. Arnold Prize Essays, edited by Stephen A. Smith. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2016.

Kester, Howard. Revolt among the Sharecroppers (1936). Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 1997.

Manley, Patricia. “The Pursuit of Land: Southern Tenancy, Manly Independence and Mobility on the Agricultural Ladder.” MA thesis, California State University San Marcos, 2014. Online at https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/concern/theses/z603qx80x?locale=en (accessed July 6, 2023).

Manthorne, Jason. “The View from the Cotton: Reconsidering the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union.” Agricultural History 64 (Winter 2010): 20–45.

Mitchell, H. L. Mean Things Happening in This Land: The Life and Times of H.L. Mitchell, Cofounder of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008.

Ownbey, Samuel. “‘The Once Peaceful Little Town’: Edmondson, Arkansas, and the Decline of African American Landownership.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2020. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3702/ (accessed July 6, 2023).

Payne, Elizabeth Ann. “The Lady Was a Sharecropper: Myrtle Lawrence and the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union.” Southern Cultures 4.2 (1998): 5–27.

Ross, James D., Jr. “‘I ain’t got no home in this world’: The Rise and Fall of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union in Arkansas.” PhD diss., Auburn University, 2004.

———. The Rise and Fall of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union in Arkansas. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2017.

“Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union Presentations.” 1975. Audio online at Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Arkansas Studies Institute (ASI) Research Portal: STFU Presentations (accessed July 6, 2023).

Whayne, Jeannie M. A New Plantation South: Land, Labor, and Federal Favor in Twentieth Century Arkansas. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996.

William H. Cobb

East Carolina University

Agriculture

Agriculture Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Cotton Pickers

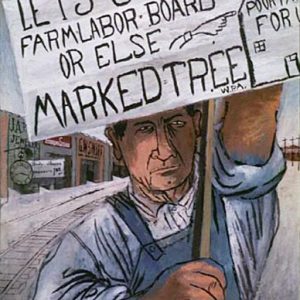

Cotton Pickers  Lest We Forget by Ben Shahn

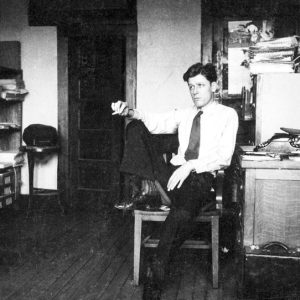

Lest We Forget by Ben Shahn  Harry Mitchell

Harry Mitchell  Southern Tenant Farmers Museum

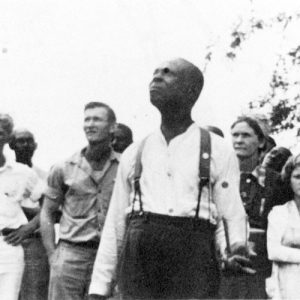

Southern Tenant Farmers Museum  Southern Tenant Farmers' Union

Southern Tenant Farmers' Union

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.