calsfoundation@cals.org

Tulip (Dallas County)

The town of Tulip, which flourished between 1842 and 1862, at one time was regarded as a center of higher education. Destruction of property during the Civil War and the changed economy of Reconstruction brought a halt to the community, which today consists of a few houses, several churches, three abandoned commercial buildings, and the ruins of one plantation.

After Arkansas became a state in 1836, many people came from the eastern United States—especially Tennessee and North Carolina—to settle in the area. For a time, the settlement was called Brownsville, after Tyre Harris Brown; then it was known as Smithville, after Colonel Maurice Smith. The colonel reportedly said that the town should be called Tulip rather than Smithville because, “There are more tulip trees growing here than Smiths.” Others say that the name Tulip represents an initialism for the five points of Calvinism: Total Depravity, Unconditional Election, Limited Atonement, Irresistible Grace, and the Perseverance of the Saints. Tulip was described at the time as a cultured and wealthy community. The Bird brothers—Joseph, Nathaniel, and William—established a pottery business in the southern part of the settlement beginning in 1843, using the native clay. Their business was purchased by John C. Welch in 1861.

Dallas County was formed in 1845. Until this time, Tulip was part of Clark County. Though the community was never incorporated, it was a named stop on the Chidester stagecoach route, which ran from Camden (Ouachita County) to Little Rock (Pulaski County); mail was delivered two or three times a week in the 1840s and 1850s. The 1850 census recorded in Smith Township (which included Tulip) “381 white males, 319 white females, 538 male negroes, and 458 female negroes”; all of the African American residents listed in the census for Smith Township were slaves. At least eleven plantation owners possessed more than twenty slaves each.

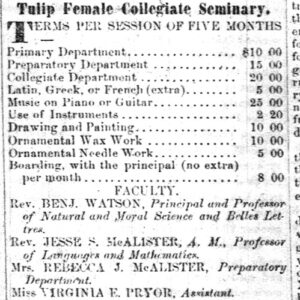

The first effort to establish a school was undertaken in 1845 by Madame d’Estimauville de Beau Mouchel. Community leaders at first planned to name the town d’Estimauville in her honor, but she left the town that same year. The residents considered her to be “of poor moral fiber” after Solon Borland, the father of her child, married a different woman in Little Rock. Four years later, George Douglass Alexander opened the Alexander Institute in Tulip. The following year, he brought in more teachers and divided the institute into two schools: the Arkansas Military Institute and the Tulip Female Collegiate Seminary. These schools attracted students from as far away as Little Rock and Camden and also drew attention from the state’s leaders. Albert Pike delivered the commencement address at the female seminary in 1852 and was invited to be an instructor at the military institute in 1861. The town earned the nickname “the Athens of Arkansas”—a nickname that has been shared by other towns in the state during other historical periods.

Arkansas’s first monthly magazine, called the Tulip, began publication in Tulip around 1850. Benjamin J. Borden was the editor. He had come to Tulip from Little Rock, where he had been an editor of the Arkansas Gazette.

The Methodist Church, South, began running the Tulip Female Collegiate Seminary in 1858, changing its name to the Ouachita Conference Female College. The military institute disbanded in 1861 when its faculty and student body were mustered into the Confederate army, and the female college was also closed during the course of the war.

Thomas Jefferson Reid, whose family lived in Tulip, was a physician and a colonel in the Confederate army during the Civil War. He led troops in the Twelfth Arkansas Infantry and the Second Arkansas Cavalry.

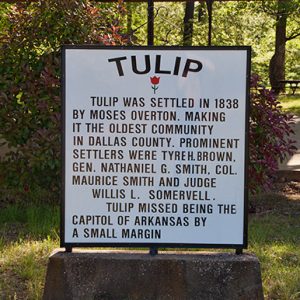

The Skirmish at Tulip occurred in 1863 while the Engagement at Jenkins’ Ferry was fought near Tulip in 1864; some homes and estates of the area were burned to the ground during the Union retreat toward Little Rock. Most of the war-related destruction, however, was caused by abandonment and neglect of the buildings rather than deliberate destruction. Almost the entire male population of the area was absent during the last stages of the war, and few families returned to rebuild. On the other hand, cotton continued to be cultivated in the region during Reconstruction. Future Little Rock attorney Scipio Jones attended school in the Tulip area in the 1870s. Tulip allegedly missed becoming the state capitol by just a few votes. The area has also remained known for pottery works: the Welch Pottery Works are listed on the National Register of Historic Places, as are the Tulip Cemetery and the Butler-Matthews Homestead.

For additional information:

Brown, Sarah. “Dallas County Multiple Resource Area.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form, 1983. Online at https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/a71672d8-b647-4f6b-a73b-cbf44aeb418e (accessed November 18, 2022).

The Goodspeed Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Southern Arkansas. Chicago: The Goodspeed Publishing Co., 1890.

Huckaby, Elizabeth Paisley, and Ethel C. Simpson, eds. Tulip Evermore: Emma Butler and William Paisley, Their Lives in Letters 1857–1887. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1985.

Smith, Herschel Kennon, Jr. “Tulip in Her Glory.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 17 (Spring 1958): 68–72.

Smith, Jonathan Kennon. The Romance of Tulip Ridge. Baltimore: Deford and Company, 1966.

Smith Family Papers. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Dixie Covington Howard

Maumelle, Arkansas

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Dallas County Map

Dallas County Map  Entering Tulip

Entering Tulip  Tulip Sign

Tulip Sign  Tulip Cemetery

Tulip Cemetery  Tulip Church

Tulip Church  Tulip Church

Tulip Church  Tulip Community Building

Tulip Community Building  Tulip Community Building

Tulip Community Building  Tulip Female Collegiate Seminary Ad

Tulip Female Collegiate Seminary Ad  Tulip-Princeton Fire Department

Tulip-Princeton Fire Department

The history says much about the way the community once was and could be again. Just a few votes short of being the capital of the state.

Churches in Tulip:

The Masonic Lodge was built before 1840, and it housed the Baptists and the Presbyterians until the Presbyterians built a church in 1851. That still housed both congregations until the Baptists built a church in 1957.

The United Methodist church was built in 1844; it was torn down in 1924 and rebuilt.

Tulip’s Presbyterian church was built in 1851; it blew down and was rebuilt in 1959.

Toones Chapel, an African Methodist Episcopal church, was built in 1914.

The 1850 census has a freed black family (a shoemaker) living next to white doctors and lawyers. The source is entry 611 from Tulip’s 1850 census. There are likely more freedmen and women. The area was very progressive and the slaves were uncommonly educated.