calsfoundation@cals.org

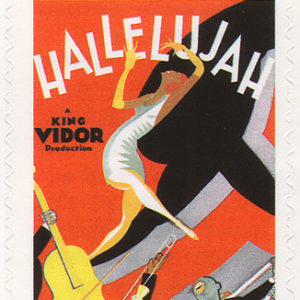

Hallelujah

Hallelujah (1929), one of the earliest Hollywood feature films shot on location in Arkansas, was innovative in several ways. It was the first talking picture made by popular director King Vidor and one of the first Hollywood pictures with an exclusively African American cast. It also introduced an early form of sound dubbing.

Vidor had wanted to make a movie with an all-Black cast for many years, but studio chiefs at Metro Goldwyn Mayer (MGM) rejected the idea until Vidor suggested making a musical. Even then, Vidor had to defer his usual $100,000 directing salary against any of the film’s profits.

Hallelujah tells the story of a young sharecropper-turned-preacher who must fight the temptations of a beautiful city girl. The musical score includes spirituals, field songs, blues numbers, and two songs by Irving Berlin. Vidor shot parts of the film on location in the South. He flew the cast and crew to Memphis, Tennessee, in October 1928. Scenes of cotton picking and outdoor church revivals were shot on both sides of the Mississippi River. The climactic scene was shot in Ten Mile Bayou near West Memphis (Crittenden County).

Vidor encountered technical problems while shooting in Arkansas and Tennessee. His sound recording equipment did not arrive, and he had to shoot scenes without sound, adding dialogue and music in the editing room. While some scenes suffer from Vidor’s primitive use of post-synchronized sound, the technique inspired him to add expressionistic effects to several sequences. The swamp scene shot in Arkansas was particularly enhanced by the addition of eerie-sounding birds and gurgling water.

Most critics praised the film, but many Black viewers found it full of stereotypes and cultural misrepresentations. Although the film was only a moderate box office success, Vidor received an Oscar nomination for his direction.

In 2008, a U.S. postage stamp was issued to commemorate the film as part of the United States Post Office Vintage Black Cinema stamp series.

For additional information:

Berry, S. Torriano, and Venise T. Berry. The 50 Most Influential Black Films: A Celebration of African-American Talent, Determination, and Creativity. New York: Kensington Publishing, 2001.

Cripps, Thomas. Slow Fade to Black: The Negro in American Film, 1900–1942. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Durgnat, Raymond. King Vidor, American. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.

Ben Fry

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment Movies

Movies Hallelujah Stamp

Hallelujah Stamp

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.