calsfoundation@cals.org

Movies

aka: Film

aka: Motion Pictures

Even though most American motion picture production has focused on the East Coast or West Coast, Arkansas has made important contributions to cinematic history. Several successful movie stars and directors were born in Arkansas, and the state has hosted the production of several important motion pictures. Since the 1960s, Arkansas’s state government has participated in the promotion of motion picture production, and in the 1990s, Arkansas began hosting film festivals that have captured worldwide attention.

The connection between Arkansas and the motion picture business begins with the earliest of American movies. Most scholars consider Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery (1903) the first step in developing a Hollywood style of filmmaking. Featured in three roles in that short movie was Max Aronson of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), better known as Gilbert M. “Broncho Billy” Anderson. Anderson played Broncho Billy in several successful westerns, starting in 1907; the role made him the first western movie star. He co-founded Essanay Studios with his partner, George K. Spoor, to produce Broncho Billy pictures. The studio also produced one-reelers with Charlie Chaplin. Anderson received an honorary Oscar in 1958.

Anderson was only the first of several Arkansas-born motion picture actors to succeed in Hollywood. Dick Powell, who starred in musicals in the 1930s and took on tough-guy roles in the 1940s, was born in Mountain View (Stone County) in 1904. Alan Ladd, born in Hot Springs (Garland County) in 1913, was another tough guy, best known for his performance in the title role of the western Shane (1953). Arthur Hunnicutt, born in Gravelly (Yell County) in 1911, was a familiar face in many classic Hollywood movies, playing likeable yokels. Melinda Dillon, who had featured roles in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and the holiday classic A Christmas Story (1983), was born in Hope (Hempstead County) in 1939. Mary Steenburgen, who won an Academy Award for her supporting role in the 1980 comedy Melvin and Howard, was born in Newport (Jackson County) in 1953. Billy Bob Thornton, born in Hot Springs in 1955, has starred in many motion pictures, including the award-winning Sling Blade (1996), which he wrote and directed.

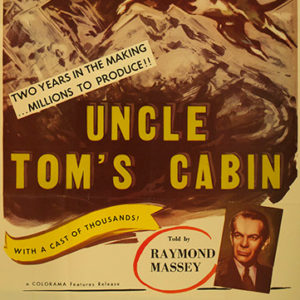

Hollywood also has made the occasional trip to Arkansas. Its first excursion to the state was made in the fall of 1926 aboard a steamboat anchored in the port of Helena (Phillips County). Universal Pictures chartered the boat to shoot scenes for a big-budget version of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Even though the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy protested the shooting of the picture, about 200 locals participated in the production. The first movie filmed mostly entirely in the state was 1928’s Souls Aflame, a silent film shot in Norfork (Baxter County) that centered upon a Reconstruction-era feud. The movie was a commercial failure, and no copy of it survives.

In 1928, award-winning silent-film director King Vidor shot his first talking picture in Arkansas and Tennessee. Hallelujah (1929) was the story of an African-American sharecropper-turned-preacher who must fight the temptations of a beautiful city girl. Vidor shot scenes of cotton picking and outdoor church revivals near the banks of the Mississippi River and shot the movie’s climax in a swamp near West Memphis (Crittenden County). While the musical with an all-black cast was only a moderate box office success, it received an Oscar nomination for Vidor’s direction.

More than a decade later, an Arkansas landmark was featured in one of the most popular movies of all time. The opening credits of Gone with the Wind (1939) include several short scenes of Southern locations, including the Old Mill in North Little Rock (Pulaski County). The shot lasts only a few seconds, but it placed Arkansas again into motion picture history.

Hollywood did not return to Arkansas until 1956, when director Elia Kazan took a film crew to Piggott (Clay County) to shoot scenes for A Face in the Crowd, starring Andy Griffith. Griffith, in his first motion picture role, portrays Lonesome Rhodes, a folksy Arkansas hobo who becomes a ruthless television star. Kazan’s crew shot for two weeks in Piggott and showed its appreciation for the community by funding the completion of a public pool. Terror at Black Falls, a short Western, was filled in Scotland (Van Buren County) in 1959 and released in 1962.

In the late 1960s, Governor Winthrop Rockefeller began promoting the state to filmmakers by offering help from his staff in scouting locations and from state troopers during production. In the next decade, Arkansas became a regular shooting site for independent films.

Director/producer Roger Corman made two movies in Arkansas, the first of which was Bloody Mama (1970), which Corman directed. Bloody Mama starred Shelley Winters as Ma Barker, the infamous matriarch of a Prohibition-era crime family. Corman, who gave many young filmmakers their first big break in the business, cast twenty-six-year-old Robert De Niro in one of his earliest film roles as one of Ma Barker’s sons. Bloody Mama was shot in and around Mountain Home (Baxter County) and Little Rock (Pulaski County). More than 150 Baxter County residents were hired as extras, including the county judge and the mayor of Mountain Home. The film featured violence and some nudity, which prompted a group of Batesville (Independence County) residents hired for bit parts to walk off the set in Little Rock when the filming “really started getting gross.”

Corman returned his film crew to the state two years later to shoot another exploitation film featuring violence and nudity, but with a fresh young director at the helm. Boxcar Bertha (1972) was Martin Scorsese’s first Hollywood assignment. The film was another crime film set in the 1930s, this time starring Barbara Hershey as the title character. The film was shot near Camden (Ouachita County) and included scenes aboard the steam locomotive on the Possum Trot line at Reader (Ouachita County). During the shooting of this movie, Hershey handed Scorsese a copy of The Last Temptation of Christ, a book the director would later turn into one of his most controversial films.

Another cult classic was shot partly in Arkansas between the two Corman films. Two Lane Blacktop (1971) was the story of two nameless drifters—played by singer James Taylor and Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson—who race a 1955 Chevy across the United States. Scenes were shot on several Arkansas highways and on a ride across the Arkansas River on Toad Suck Ferry in Faulkner County just days before ferry rides were suspended because of the opening of the new Toad Suck Bridge.

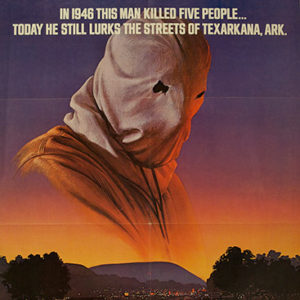

Arkansas native Charles B. Pierce made several films in Arkansas in the 1970s. His first movie was a docudrama about a Bigfoot-like creature rumored to live near Fouke (Miller County). The Legend of Boggy Creek (1973) was shot in Arkansas, using local residents who claimed to have seen or heard the monster, allowing them to tell their stories or reenact them for the camera. The movie, which cost only $160,000, grossed more than $22 million. Pierce used this success to fund additional movies, including two more shot in Arkansas: Bootleggers (1974), a comedy about moonshiners, with a cast that included Jaclyn Smith before she became famous as one of television’s Charlie’s Angels, and The Town that Dreaded Sundown (1977), based on the true story of the Phantom Killer, who stalked the residents of Texarkana (Miller County) in 1946.

Burt Reynolds, who had recently gained fame for his performance in Deliverance (1972) and his controversial centerfold in Cosmopolitan magazine, came to Arkansas to shoot the redneck action film White Lightning (1973). Cast as the female lead was Jennifer Billingsley, who had grown up in Arkansas. Locations included the Benton Speedbowl, the Tucker Unit of the Arkansas Department of Correction, and a scene of Reynolds driving his car onto a barge on the Arkansas River. About 100 Arkansans had secondary roles and parts as extras.

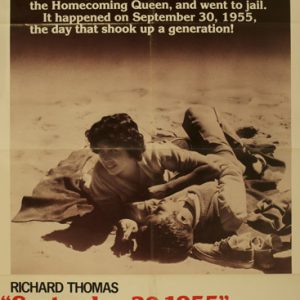

James Bridges, a successful Hollywood writer and director, returned to his home state to shoot a movie based on his life. September 30, 1955 (1978) was the story of a young man (played by Richard Thomas) and his response to the sudden death of his hero James Dean. Bridges was attending Arkansas State Teachers College, now the University of Central Arkansas (UCA), in Conway (Faulkner County) when Dean died, and he chose to shoot scenes at several Conway locations.

Another Arkansas native directed several low-budget horror and science fiction films in the state in the 1970s. Harry Thomason later became famous as the director of the television series Designing Women and Evening Shade, produced by his wife, Linda Bloodworth-Thomason. His Arkansas productions included Encounter with the Unknown (1973), The Great Lester Boggs (1975), and So Sad about Gloria (1975).

In 1979, the Arkansas Industrial Development Commission (now the Arkansas Economic Development Commission) formed the Arkansas Motion Picture Development Office (now the Arkansas Film Unit) to promote film production in the state. The film office would provide movie producers with administrative support and offer training opportunities for residents to learn about film production. Also, the legislature, spurred by Joe Glass, the first director of the state’s Office of Motion Picture Development, authorized a sales tax refund for film companies working in the state to encourage production.

In the 1980s, Arkansas became a popular location for several television movies, including the docudrama Crisis at Central High (1981) about the 1957 desegregation of Little Rock’s Central High School, the Civil War miniseries The Blue and the Gray (1982, produced by Thomason), and Under Siege (1986), in which the Arkansas State Capitol doubled for the U.S. Capitol in Washington DC during a terrorist attack.

Director Norman Jewison chose Arkansas for his production of A Soldier’s Story (1984) about the investigation of the death of a black soldier stationed in the South at the end of World War II. Fort Chaffee in Sebastian County doubled for the 1940s army base and Clarendon (Monroe County) for a nearby Louisiana town. Lamar Porter Field in Little Rock was the site of a baseball game between black and white players shot for the movie. The UCA baseball team portrayed the white players.

End of the Line (1987) was produced by Mary Steenburgen and written and directed by Jay Russell, who was born in North Little Rock. The cast featured Levon Helm, a native of Marvell (Phillips County), who was one of the lead vocalists and the drummer in the rock group The Band. Helm and Wilford Brimley played veteran railroad employees who rebel against plans to shut down the line by commandeering a train engine. The film was shot in Scott (Pulaski and Lonoke Counties), Benton (Saline County), Lonoke (Lonoke County), and the Union Pacific railroad yard in North Little Rock.

Fort Chaffee again played the part of a World War II army base in Biloxi Blues (1988), written by Neil Simon and directed by Mike Nichols. Van Buren (Crawford County) was transformed into Biloxi, Mississippi, in the 1940s, with local residents taking parts as extras. The 1995 movie The Tuskegee Airmen was also filmed in part at Fort Chaffee.

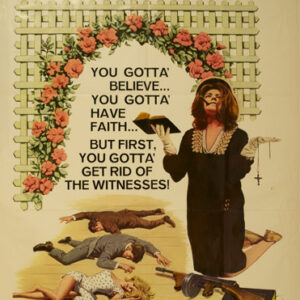

Other independent productions in the 1980s included Three for the Road (1987), shot in Hot Springs; Pass the Ammo (1988), shot in Eureka Springs (Carroll County); and Rosalie Goes Shopping (1989), shot in Stuttgart (Arkansas County).

While Arkansas continued to host documentaries and television productions in the 1990s, few theatrically released motion pictures were shot in the state, except films developed by Billy Bob Thornton. One False Move (1992), scripted by Thornton, was shot near Brinkley (Monroe County) and Cotton Plant (Woodruff County), and Sling Blade (1996), written and directed by Thornton, was shot in Saline County. Thornton received an Academy Award for his Sling Blade screenplay and a nomination for his performance in the film as Karl Childers, a simple-minded man who reenters society after spending most of his life in a mental institution. Arkansan Natalie Canerday had a featured role, and several other Arkansans appeared in supporting roles.

Another major motion picture shot on Arkansas soil in the 1990s was based on the work of an Arkansas native. The Firm (1993) was adapted from a novel by best-selling author John Grisham, a native of Jonesboro (Craighead County). Some scenes were shot in West Memphis. Hallmark Hall of Fame Productions filmed a television movie version of Grisham’s A Painted House, which aired on the CBS network in 2003. A major part of the movie was shot in Lepanto (Poinsett County) for the town settings and Clarkedale (Crittenden County) for the rural settings.

The state has hosted several motion picture productions since 2004, including two big budget pictures, Walk the Line (2005), about Arkansas native and country singer Johnny Cash, and Elizabethtown (2005). Chrystal (2004), shot in northeast Arkansas, starred Thornton and Arkansas native Lisa Blount, who co-produced the movie with her husband, Ray McKinnon. North Little Rock native Joey Lauren Adams made her directorial debut with Come Early Morning (2006), which she shot in and around her hometown. The two latter movies debuted at the Sundance Film Festival in Utah. Critically acclaimed independent writer/director Jeff Nichols of Little Rock has made four movies: Shotgun Stories (2007), which was filmed in Arkansas; Take Shelter (2011); Mud (2013), which was shot in the Arkansas Delta; and Loving (2016). Arkansas also landed films of the popular God’s Not Dead franchise of Christian movies; God’s Not Dead 2 and God’s Not Dead: A Light in Darkness were filmed in central Arkansas in 2015 and 2017, respectively. The 2023 short documentary The Barber of Little Rock was nominated for an Academy Award in 2024.

Motion picture production in Arkansas has suffered from competition with other states and with locations outside the nation’s borders. Arkansas law provides an incentive to filmmakers by rebating the state’s sales tax to production companies that spend a minimum of $500,000 in the state during a six-month period or a minimum of one million dollars on multiple projects during a twelve-month period. In 2009, the Arkansas General Assembly the Digital Product and Motion Picture Industry Development act, giving a twenty percent rebate for film projects in the state and an additional ten percent rebate for hiring Arkansas-based production crews. However, most surrounding states offered production companies additional tax incentives. Arkansas’s smaller incentives may explain why motion picture production in the state since the early 1990s was limited mostly to productions by filmmakers with Arkansas ties. Act 517 of 2021 raised the incentives for filmmakers, especially those filmmakers who spend money or hire crew from a county deemed “economically distressed” by the Arkansas Economic Development Commission.

The state has also been home to a number of significant film festivals. The Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival, which began in 1992, screens approximately 100 films, including productions by Arkansans. The Pine Bluff Film Festival, started in 1994 (but suspended in 2008), screened classic Hollywood films, including silent pictures, and highlighted a well-known Hollywood star each year as its special guest. The Ozark Foothills FilmFest began in 2001 and presents a variety of films, including productions by Arkansans, in venues in Batesville. The Little Rock Film Festival began in 2007 as an international festival that also focused on promoting film in Arkansas; it ended its run, however, in fall 2015. In 2015, the Bentonville Film Festival, co-founded by actress Geena Davis and sponsored by Walmart, held its first annual festival; the festival’s focus is diversity in film.

With the advent of digital technology and the reduced cost for narrative filmmaking, several Arkansans have started their own motion picture companies in the state. Thus far, they have met with limited success but hope to usher in a new era in the history of Arkansas-made motion pictures.

In 2011, the nonprofit Arkansas Motion Picture Institute (AMPI) was founded with the mission of fostering growth and excellence in movies, television, and digital media. Courtney Pledger was named the group’s first executive director in 2012. The AMPI serves as an umbrella organization for all the state’s major film festivals. In 2012, a public/private partnership called the Arkansas Production Alliance was launched, seeking to join the efforts of the Little Rock Regional Chamber of Commerce, the Northwest Arkansas Council, and the Arkansas Film Commission to attract film projects to the state.

In March 2017, it was announced that filmmaker Jeff Nichols would serve as chairperson of the newly formed Arkansas Cinema Society, an organization with the aim to build a film community in the state of Arkansas.

For additional information:

Alexander, Olivia. “Pull-Out of Movie Leads to Worries.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, July 7, 2022, pp. 1B, 3B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/jul/07/arkansas-film-workers-react-to-abortion-protest/ (accessed July 7, 2022).

arFilm: Arkansas Production Alliance. http://arkansasproduction.com/ (accessed September 3, 2021).

“Arkansas in the Movies: Monsters, Murder, and Moonshine.” Arkansas Times. February 1987, pp. 32–41, 62–64.

Cochran, Robert, and Suzanne McCray. Lights! Camera! Arkansas! From Broncho Billy to Billy Bob Thornton. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2015.

Franco, Cheree. “The Price of ‘Made in Arkansas’: A Look at Arkansas’s Film Incentive Package.” Arkansas Times, June 20, 2012. Online at http://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/the-price-of-made-in-arkansas/Content?oid=2301682 (accessed May 21, 2022).

Hot Springs Documentary Film Institute. http://www.hsdfi.org/ (accessed May 21, 2022).

Jackson, Robert. Fade In, Crossroads: A History of the Southern Cinema. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Lewis, Bill. “After Success of ‘Boggy Creek,’ ‘Bootleggers,’ Distributors Seeking Out Arkansas Filmmaker.” Arkansas Gazette, August 10, 1975, p. 22A.

Lights!Camera!Arkansas! Old State House Museum. https://www.oldstatehouse.com/traveling-exhibits-list/lights-camera-arkansas (accessed September 3, 2021).

Stanley, Tim. “Part of the Big Picture: Many Hollywood Heavyweights Enjoyed the Dawn of Stardom in Films Made in the Heart of Arkansas.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 14, 2000, p. 10W.

Ben Fry

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Adams, Julie

Adams, Julie American Made

American Made Andrews, Lloyd

Andrews, Lloyd Arkansas Judge

Arkansas Judge Arkansas Swing, The

Arkansas Swing, The Arts, Culture, and Entertainment

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment Besser, Matthew Gregory (Matt)

Besser, Matthew Gregory (Matt) Brubaker

Brubaker Come Next Spring

Come Next Spring Daddy and Them

Daddy and Them Davis, Gail

Davis, Gail Day It Came to Earth, The

Day It Came to Earth, The Devil's Knot

Devil's Knot Dial, Rick

Dial, Rick Die Goldsucher von Arkansas

Die Goldsucher von Arkansas Down in "Arkansaw"

Down in "Arkansaw" Epperson, Tom

Epperson, Tom Ernest Green Story, The

Ernest Green Story, The Evans, Dale

Evans, Dale Fighting Mad

Fighting Mad Flippen, Jay C.

Flippen, Jay C. Gerard, Gil

Gerard, Gil Gospel of Eureka, The

Gospel of Eureka, The Great Balls of Fire!

Great Balls of Fire! Greer, Stuart

Greer, Stuart I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

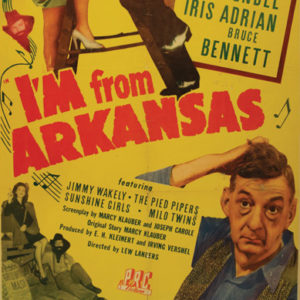

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings I'm from Arkansas

I'm from Arkansas Kettles in the Ozarks, The

Kettles in the Ozarks, The Lester, Ketty

Lester, Ketty Man Outside

Man Outside Marjoun and the Flying Headscarf

Marjoun and the Flying Headscarf Moore, Rudy Ray

Moore, Rudy Ray Ozark Sharks

Ozark Sharks Paradise Lost

Paradise Lost Primary Colors

Primary Colors Purcell, Lee

Purcell, Lee Sammon, Winona

Sammon, Winona Searcy (White County)

Searcy (White County) Sharkansas Women’s Prison Massacre

Sharkansas Women’s Prison Massacre She Couldn't Say No

She Couldn't Say No Shelter

Shelter Tom Sawyer, Detective

Tom Sawyer, Detective True Grit

True Grit Underwood, Sheryl

Underwood, Sheryl War Room, The

War Room, The Warfield, William Caesar

Warfield, William Caesar Wishbone Cutter

Wishbone Cutter Woman They Almost Lynched

Woman They Almost Lynched Joey Lauren Adams

Joey Lauren Adams  Broncho Billy Anderson

Broncho Billy Anderson  Lloyd "Arkansas Slim" Andrews with Tex Ritter

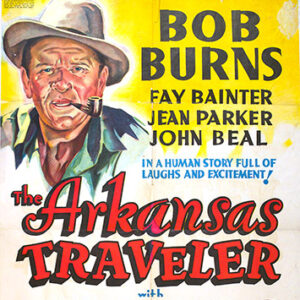

Lloyd "Arkansas Slim" Andrews with Tex Ritter  The Arkansas Traveler

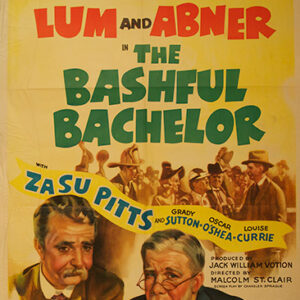

The Arkansas Traveler  The Bashful Bachelor

The Bashful Bachelor  Bloody Mama

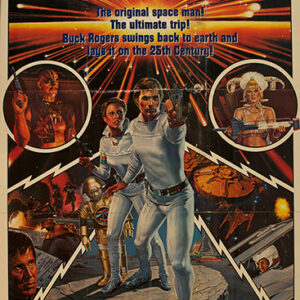

Bloody Mama  Buck Rogers

Buck Rogers  David Gordon Green

David Gordon Green  Arthur Hunnicutt

Arthur Hunnicutt  I'm from Arkansas

I'm from Arkansas  The Last Ride

The Last Ride  Melvin and Howard

Melvin and Howard  Old Mill

Old Mill  Dick Powell

Dick Powell  September 30, 1955

September 30, 1955  The Town that Dreaded Sundown

The Town that Dreaded Sundown  Uncle Tom's Cabin

Uncle Tom's Cabin  White Lightning Car

White Lightning Car

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.