calsfoundation@cals.org

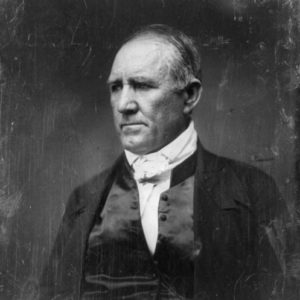

Sam Houston (1793–1863)

Sam Houston was the governor of Tennessee, twice president of the Republic of Texas, and later senator and governor of the state of Texas. From May 1829 until November 1832, Houston lived in Arkansas Territory among the Cherokee.

Sam Houston was born to Samuel Houston and Elizabeth Paxton Houston on March 2, 1793, at Timber Ridge Plantation in Rockbridge County, Virginia. Moving to Maryville, Tennessee, in 1807, Houston cleared land and clerked in a mercantile establishment. As he “preferred measuring deer tracks in the forest to tape and calico in a country store,” Houston went to live with John Jolly’s band of Cherokee and was given the name Colonneh (“Raven”). Subsequently, he taught school and volunteered in the War of 1812, distinguishing himself at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend against the Creek (Muscogee) Indians.

From 1817 to 1818, Houston served as an Indian subagent to the Cherokee and helped several bands resettle in Arkansas and present-day Oklahoma. He subsequently read for the bar and was an early supporter of General Andrew Jackson’s presidential bid. After serving in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1823 to 1827, Houston was elected governor of Tennessee. He planned to run for reelection; however, his marriage to eighteen-year-old Eliza Allen fell apart under mysterious circumstances, and Houston resigned his office on April 16, 1829, as a result of this domestic turbulence.

A few days later, Houston left Tennessee for “the wigwam of his adopted father, the chief of the Cherokees, in Arkansas.” Traveling in disguise by the steam packet Red Rover, by flatboat, and by steamboat to Arkansas Territory, Houston arrived in Little Rock (Pulaski County) on May 8, 1829. Houston had apparently heard rumors that he was contemplating a filibustering expedition (an unauthorized military incursion to foment or support a revolution) to Texas and obliquely denied them in a letter; he was, however, in good enough spirits to try to mend bridges between Andrew Jackson and Colonel Robert Crittenden, the acting governor, and to report that he intended to engage in a summer buffalo hunt.

Houston then took passage upriver aboard the Facility and landed at Tahlontuskee, near Webbers Falls (now in Oklahoma), where he was allegedly told by Jolly, “My wigwam is yours—my home is yours—my people are yours—rest with us.” (Jolly’s “wigwam” was in fact a plantation house.) During June and July, Houston visited in the region, served as Jolly’s representative at a conclave (where he was unsuccessful in preventing a declaration of war between the Cherokee and the Pawnee and Comanche), and wrote Jackson and others in the government on behalf of several of the tribes. In August and September 1829, when Houston was prostrated with malaria, it seems clear that he at least briefly considered going to Natchez, Mississippi. He wrote Jackson: “Your suggestion on the subject of my location in Arkansas has received my serious attention, and I have concluded, that it would not be best for me to adopt the course. In that Territory there is no field for distinction—it is fraught with factions; and if my object were to obtain wealth, it must be done by fraud, and peculation upon the Government, and many perjuries would be necessary to its effectuation!”

The following month, on October 31, 1829, Houston received his citizenship in the Cherokee Nation. While among the Cherokee, Houston wore native dress and allegedly refused to speak English. Houston’s attempt to use his Cherokee citizenship to avoid licensing as a trader, however, was rejected by the U.S. government.

In December 1829, Houston traveled to Washington DC as a representative of the Cherokee. It was at this time that Dr. Robert Mayo later claimed that Houston was organizing an expedition against Texas, having settled among the Indians in order to cloak his true intentions. Whatever the truth of this, Houston failed to get the contracts on which he bid, and he returned to Arkansas Territory in June 1830. He built a log house, “Wigwam Neosho,” took an influential Indian wife, “Talihina” (Diana Rogers Gentry), and set up as a trader. Between June 22 and December 8, Houston wrote a series of five articles for the Arkansas Gazette dealing with the status of the removed tribes and attacking the activities of their Indian agents, using the pen names “Tah-Lohn-Tus-Ky” and “Standing Bear.” These constitute the first defense of Native American rights and exposure of government corruption written by a well-known Westerner.

Houston also apparently overindulged in liquor (earning another Indian name that translated as “Big Drunk”) and even engaged in an altercation with Jolly, for which he was subsequently forced to apologize publicly. Possibly due to this, his foray into Native American politics—running for membership on the Cherokee’s National Council in the spring of 1831—ended in defeat.

In December, Houston accompanied a second Cherokee delegation to Washington, meeting Alexis de Tocqueville on the way and becoming caught up in the speculation on Texas lands. His caning of Congressman William Stanbery for slanderous remarks concerning Houston and Indian contracts led to legal proceedings in Congress. Jackson asked Houston to treat with the Comanche, leading to Houston’s arrival in Texas in December 1832. It has been claimed that when Talihina refused to accompany him, Houston left her with the title to their house, property, and two slaves. He did, however, return again to the territory in May 1833 for a meeting between the Comanche and U.S. commissioners at Fort Gibson. After this fell through, Houston obtained a power of attorney from Talihina on June 27 and spent most of the rest of his summer in Hot Springs (Garland County) recuperating from an old shoulder wound.

Jack Gregory and Rennard Strickland have argued that many of Houston’s basic attitudes were formulated during his sojourn in Arkansas Territory: “Houston’s contributions to the Indian administration are…among his most significant achievements. Reforms instituted in the Agency system…were basic and long-lasting. Treaties and agreements negotiated with Houston’s assistance provided a stable basis for Indian-White relations along the Southwestern frontier.” There is also recurring evidence for the premise that Houston’s accomplishments in Texas grew out of his initial plans for an Indian-backed empire.

Houston was active in the Texas Revolution of 1835–36 and, as commander-in-chief of the Texan army, was responsible for the stinging Mexican defeat at San Jacinto and the capture of Santa Anna. As a result, Houston was elected president of the Republic of Texas in 1836 and reelected in 1841 after a constitutionally required hiatus. When the republic was annexed to the Union in 1845, Houston served as one of the state’s first U.S. senators from 1846 to 1859. Defeated in a run for governor in 1857, he was elected to that office in 1859, and his name was even bruited about for president of the United States in 1860.

In 1861, following Texas’s secession from the Union, Houston and other officials were ordered to pledge their loyalty to the Confederacy. He wrote his “fellow citizens” that “in the name of your rights and liberties, which I believe have been trampled on” and “[i]n the name of my own conscience and my own manhood…I refuse to take this oath.” Houston was peacefully removed from the governorship and died of pneumonia in Huntsville, Texas, on July 26, 1863.

For additional information:

Burrough, Bryan, Chris Tomlinson, and Jason Stanford. Forget the Alamo: The Rise and Fall of an American Myth. New York: Penguin Press, 2021.

Campbell, Randolph B. Sam Houston and the American Southwest. 2d ed. New York: Longman, 2002.

De Bruhl, Marshall, Sword of San Jacinto: A Life of Sam Houston. New York: Random House, 1993.

Friend, Llerena. Sam Houston: The Great Designer. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1954.

Gregory, Jack, and Rennard Strickland. Sam Houston with the Cherokees, 1829–1833. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1967.

Haley, James L. Sam Houston. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002.

James, Marquis. The Raven: The Story of Sam Houston. Indianapolis, IN: The Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1929.

Williams, Amelia, and Eugene C. Barker. The Writings of Sam Houston, 1813–1863. vol. 1. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1938.

Williams, John Hoyt. Sam Houston: A Biography of the Father of Texas. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993.

Samuel Pyeatt Menefee

Charlottesville, Virginia

Sam Houston

Sam Houston

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.