calsfoundation@cals.org

Knights of Labor

The largest American labor organization of its era, the Knights of Labor (KOL) recruited workers across boundaries of gender, race, and skill. The organization claimed more than 700,000 members at its peak in 1886, and actual membership at that time may have surpassed one million. In Arkansas, membership peaked at over 5,000 in 1887, and despite the KOL’s official view of strikes as a measure of last resort, the organization led strikes in Arkansas among railroad workers, coal miners, and African-American farmhands. During the 1890s, the KOL sank into oblivion, but the organization played a pioneering role in both the unionization and political mobilization of workers in factories, mines, and farms.

Origins

Formed as a secret organization in Philadelphia in 1869, the KOL grew slowly, making no efforts at national expansion until 1878. The KOL did not reach Arkansas until late 1882. On November 22, 1882, seven men met in a blacksmith shop in Hot Springs (Garland County) with the goal of forming a local assembly of the KOL. Since the organization’s constitution required a local assembly to have at least ten members, Hot Springs Assembly 2419 was not officially formed until December 30. All of its members were white men. One of the seven founders was Dan Fraser Tomson, who became the leading figure in the Arkansas KOL over the next decade, organizing many local assemblies and holding the office of State Master Workman from 1888 to 1890. Members of the Hot Springs Assembly apparently helped organize the state’s second local assembly, Freedom Assembly 2447 (also of Hot Springs), which consisted entirely of African Americans. The KOL grew slowly and unevenly in Arkansas, with only twenty local assemblies in the state as late as 1885.

Growth and Strikes

In Arkansas, the KOL grew exponentially between 1885 and 1886, through a series of much publicized strikes (particularly in the railroad industry). The number of local assemblies in Arkansas reached 111 in 1886, and the Arkansas KOL became involved in a number of strikes that year, most notably the second Southwest railroad strike. But whereas the first Southwest strike of 1885 resulted in an unprecedented victory for the KOL against the famed “robber baron” Jay Gould, the second strike ended in defeat for the union. In Arkansas, strikers succeeded in shutting down freight traffic on the Iron Mountain Railroad for several weeks, but after engaging in a gunfight with deputy marshals, hijacking locomotives, and allegedly burning several railroad trestles, they faced court injunctions and arrests. In Texarkana (Miller County), they also faced the state militia, sent by Democratic governor Simon P. Hughes to prevent any further disturbances. The KOL also waged a strike of thirty African-American farmhands in Pulaski County who demanded a wage increase from seventy-five cents to one dollar per day in the summer of 1886. Local authorities helped crush this strike without any fatalities, in sharp contrast to a cotton pickers’ strike led by the Colored Farmers’ Alliance in Lee County five years later that resulted in approximately twenty deaths.

Political Activity

As the KOL’s efforts at labor activism foundered in the face of governmental opposition, the organization moved into the political arena. In 1886, the supposedly nonpartisan organization joined forces with the much larger Agricultural Wheel in building a biracial coalition of farmers and laborers to oppose the state’s dominant Democratic Party. The limited available evidence suggests that many Knights supported Independent Labor candidate Isom P. Langley in his unsuccessful bid to represent west central Arkansas’s Fourth District in the U.S. House of Representatives, and an independent ticket jointly nominated by members of the KOL and the Agricultural Wheel won the county elections that year in Carroll County. The KOL gave unofficial support to Union Labor Party (ULP) candidates in Arkansas in 1888 and 1890, with some Knights running for (and occasionally winning) various offices under the ULP banner, although violence and fraud kept significant ULP victories in the state to a minimum. By 1892, the ULP gave way to the Populist Party, and many leaders of the Arkansas KOL became state Populist leaders. W. B. W. Heartsill of Greenwood (Sebastian County), who served as State Master Workman of the Arkansas KOL from 1893 to 1895, unsuccessfully ran for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives as a Populist in 1892. The Arkansas KOL remained involved in the Populist Party for about as long as the two organizations remained active; in fact, Polk County in rural western Arkansas held the distinction of being both the last Populist stronghold in the state, as the party controlled county offices there into the late 1890s, and one of the last centers of KOL activity in the state during the same period.

Demise and Legacy

The failures of the Union Labor and Populist parties and the repeated defeats of KOL strikes in Arkansas—the last of which was a coal miners’ strike at Huntington (Sebastian County) in 1895—ultimately destroyed the KOL in Arkansas. Most local assemblies had disbanded by the end of the 1890s, and the last known meeting of the KOL State Assembly occurred in Hot Springs in 1906. Nevertheless, the KOL played a pioneering role in organizing workers—urban and rural, skilled and unskilled, white and black, and male and female—in Arkansas, and the union’s efforts among coal miners in the western part of the state paved the way for the organization of those workers on a larger scale by the United Mine Workers of America.

For additional information:

Baskett, Thomas S., Jr. “Miners Stay Away!: W. B. W. Heartsill and the Last Years of the Arkansas Knights of Labor, 1892–1896.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 42 (Summer 1983): 107–133.

Case, Theresa A. The Great Southwest Railroad Strike and Free Labor. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2010.

———. “The Radical Potential of the Knights’ Biracialism: The 1885–1886 Gould System Strikes and Their Aftermath.” Labor: Studies in Working Class History 4 (Winter 2007): 83–107.

Hild, Matthew. Arkansas’s Gilded Age: The Rise, Decline, and Legacy of Populism and Working-Class Protest. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2018.

———. Greenbackers, Knights of Labor, and Populists: Farmer-Labor Insurgency in the Late-Nineteenth-Century South. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007.

———. “The Knights of Labor in Arkansas: A Research Note.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 79 (Spring 2020): 59–63.

———. “Labor, Third-Party Politics, and New South Democracy in Arkansas, 1884–1896.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 63 (Spring 2004): 24–43.

Phelan, Craig. Grand Master Workman: Terence Powderly and the Knights of Labor. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000.

Rogers, William Warren. “Negro Knights of Labor in Arkansas: A Case Study of the ‘Miscellaneous’ Strike.” Labor History 10 (Summer 1969): 498–505.

Turner, Ralph V., and William Warren Rogers. “Arkansas Labor in Revolt: Little Rock and the Great Southwestern Strike.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 24 (Spring 1965): 29–46.

Matthew Hild

Georgia Institute of Technology

National Farmers’ Alliance and Industrial Union of America

National Farmers’ Alliance and Industrial Union of America Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Sovereign, James Richard

Sovereign, James Richard Knights of Labor Founders

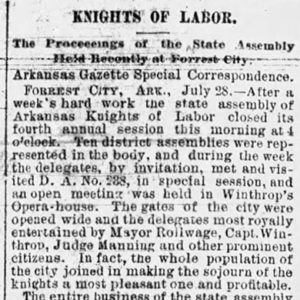

Knights of Labor Founders  Knights of Labor Story

Knights of Labor Story  Knights of Labor Story

Knights of Labor Story

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.