calsfoundation@cals.org

Southland College

Southland College emerged out of a Civil War–era mission by Indiana Quakers who came to Helena (Phillips County) in 1864 to care for lost and abandoned black children. Its founders, Alida and Calvin Clark, were abolitionist members of the Religious Society of Friends who arrived in Arkansas to render temporary relief to displaced orphans. They stayed for the remainder of their working lives, establishing the school that became the first institution of higher education for African Americans west of the Mississippi River. The school survived six decades of economic adversity and social strife.

After operating an orphanage and school in Helena for two years, in 1866, the Clarks, with the vital assistance of the officers and men of the Fifty-sixth Colored Regiment (U.S. Army), moved their charges to a rural location in Phillips County, nine miles northwest of Helena. Here, they established the school and its associated Quaker meeting under the auspices of the Indiana Yearly Meeting. In the beginning, Southland, housed in rough plank buildings erected through the voluntary labor of black soldiers, remained a school for orphans. But given the near-obsession of freed slaves to acquire literacy coupled with the paucity of educational opportunities available for black citizens in the Arkansas Delta, Southland quickly began to attract the children of local black farmers as well as a smattering of boarding students from throughout the Mississippi River Valley, including the “mulatto” children of white planters.

For over twenty years Alida Clark was, in the words of a fellow Quaker, “the moving spirit of the place,” caring for children, supervising the school, soliciting funds, and proselytizing on behalf of the Society of Friends. Calvin kept the books and oversaw farming operations both on Quaker-owned land that helped support the school and on hundreds of acres gradually acquired by the Clarks. As the school’s reputation began to spread throughout the Arkansas Delta during the 1870s, enrollment grew from a few dozen to as many as 200, always depending on the success or failure of the cotton crop upon which the livelihood of rural blacks was based. Contributing to a steady growth of student population was the practice by black farmers of leasing or purchasing land near the school to secure an otherwise unavailable education for their children. Eventually, a rural community grew up, taking its name from the school it surrounded.

In 1876, the Missionary Board of Indiana Yearly Meeting, impressed by the number of badly needed black teachers already produced by their school and feeling compelled “to advance… educational… interests in… Arkansas and especially to qualify teachers,” took the necessary steps to have Southland College designated a diploma-granting institution. Fittingly, the first three graduates were all orphans raised from childhood by the Clarks. Given the simple course of study required for graduation, “college” was probably always a misnomer. Still, those trained at Southland were undoubtedly better prepared than the vast majority of individuals teaching in what passed for a black educational system in Arkansas.

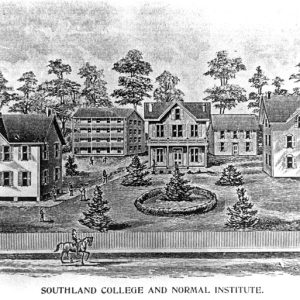

By the mid-1880s, five permanent buildings on the Southland campus provided educational possibilities for upwards of 300 students. However, dissatisfaction among a second generation of Southland patrons, disloyalty from dissident faculty, and difficulties with some members of the controlling Missionary Board all contributed to the Clarks’ decision to resign as superintendent and matron in 1886, ending an era in Southland’s history.

For a generation after the departure of Calvin and Alida Clark, Southland was troubled by intermittent strife and instability. For a variety of reasons, none of the school’s half dozen leaders between 1886 and 1903 fit comfortably into the job or the community. Enrollment fluctuated, but in 1902, it fell to a dismal low of 100. Southland was lifted out of this nadir with the arrival of Harry C. and Anna B. Wolford, a Quaker couple from Ohio, whose tenure in office and standing in the local black community came to rival even that of the Clarks. At the end of Harry Wolford’s first decade in office, Southland’s student population had increased to more than 400, while per capita expenditure was reduced by half. More importantly, Wolford enhanced his standing among black people in Phillips County not only by accepting every child who applied into Southland’s overcrowded classrooms and dormitories but also by acting as a financial consultant, real estate broker, and banker for local farmers. At the same time, Southland’s director managed to accommodate himself to Helena’s white business community, who viewed the school as a non-threatening force for harmony and stability in black-white relations.

Except for a single year’s hiatus, the Wolfords guided Southland from 1903 through the social and economic upheavals of the World War I era, the dangerous postwar racial tensions surrounding the Elaine Massacre, and into the 1920s. In the meantime, the Indiana Yearly Meeting, in hopes of shoring up the always fragile financial circumstances of its Arkansas mission school, transferred control of Southland to a national Quaker body, the Home Missions Board of Five Years Meeting of Friends. This organization, in turn, determined that the school, re-christened Southland Institute in 1917, should cease to serve only a local clientele and strive to become a Quaker academy of national standing along the lines of the Tuskegee and Hampton institutes.

While the Friends Home Missions Board (HMB), working in conjunction with the Rockefeller General Education Board and other national bodies supporting black education, conceived a noble vision, their high-minded reach far outstretched their financial grasp. Furthermore, Wolford had no interest in seeing “his” school turned into a semi-elite national academy. When the HMB appointed a new principal, F. Raymond Jenkins, an idealistic young Friend who had embraced the “Negro problem” during a year at Hampton Institute, as the man who would oversee Southland’s transition, Wolford resigned in opposition.

Southland’s final years witnessed the unfortunate juxtaposition of high hopes for a revived and rehabilitated school of national standing and the reality of increasing fiscal inadequacy and growing local alienation. Jenkins was dedicated and energetic, but he had little sense of the cultural factors that caused serious resentment among local people to the “improvements” he introduced. This opposition was exacerbated by Wolford’s efforts to undermine Jenkins’s status among the school’s potential patrons. After a troubled year during which enrollment slipped to less than 100, Jenkins left Arkansas to head up a national fundraising effort with a view to building an entirely new school in a new location. Despite moments of elation when it seemed as if the HMB’s exalted expectations could be met, it proved impossible to secure the financial resources necessary to keep the school open. At the end of the school year in 1925, the HMB admitted defeat and, in Quaker parlance, “laid down” the school.

The closing of Southland inevitably brought an end to Quaker connections in the Arkansas Delta. In the 1930s, the land was sold to the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which operated a school called Walters-Southland Institute that never flourished and closed after World War II. A tiny rural community called Southland still exists in Phillips County, but no physical evidence of the school remains. Nonetheless, Southland College is remembered for the educational and spiritual possibilities it provided and for the determination and sacrifices of a small body of black Arkansans who joined with their Northern Quaker brethren to sustain an institution that offered dignity and hope through a time when these were rare commodities for black Arkansans.

For additional information:

Kennedy, Thomas C. “Another Kind of Emigrant: Quakers in the Arkansas Delta, 1864–1925.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 55 (Summer 1996): 199–220.

———. A History of Southland College: The Society of Friends and Black Education in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2009.

———. “The Last Days at Southland.” The Southern Friend 8 (Spring 1986): 3–19.

———. “Rise and Decline of a Black Monthly Meeting: Southland, Arkansas, 1864–1925.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 50 (Summer 1991): 115–139.

———. “Southland College: The Society of Friends and Black Education in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 42 (Autumn 1983): 207–238.

Kirkman, Dale P. “Southland College.” Phillips County Historical Quarterly 3 (September 1964): 30–33.

Lives Transformed: The People of Southland College. Digital Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries. http://digitalcollections.uark.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/Southland (accessed January 25, 2023).

Southland College Papers. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Thomas C. Kennedy

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Alida Clawson Clark

Alida Clawson Clark  Calvin Clark

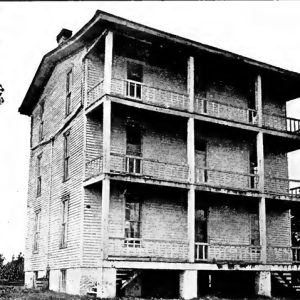

Calvin Clark  Hazard Hall

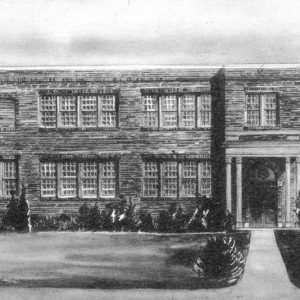

Hazard Hall  Matthews Hall

Matthews Hall  Southland College

Southland College

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.