calsfoundation@cals.org

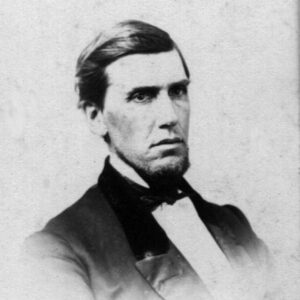

Calvin Comins Bliss (1823–1891)

Calvin Comins Bliss was in search of challenges when he and his new wife Caroline came to Arkansas from New England in 1854. He was involved in many business and other ventures including real estate, publishing, and politics. During the Civil War, he served for a time in the Union army, became the first lieutenant governor of Arkansas, and participated in establishing the new constitution that abolished slavery. His resourceful wife taught school and took care of the family, even traveling back across the front lines to New England in wartime.

Calvin Bliss was born on December 22, 1823, in Calais, Vermont, the son of farmers William and Martha Bliss. He was the first of their four children. He attended Hamilton Literary and Theological Institution (now Colgate University) in Hamilton, New York, entering with the class of 1849 although he left in 1847, most likely with others who left when faculty forbade abolitionist activities. He worked at a variety of jobs in New York, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.

Bliss married Caroline “Carrie” Eastman on September 5, 1854, in Bradford, Maine. Carrie was then a teacher who had attended Mount Holyoke Female Seminary (now Mount Holyoke College). They set out for the Helena (Phillips County) area the next day. There, they established a school for “misses,” with Bliss as principal and his wife as teacher. Bliss also worked as a purchasing agent and became involved in real estate. After a few years, they moved to Batesville (Independence County), where Bliss worked as a land agent. They owned a fifty-six-acre farm and eventually had three children.

Despite the onset of the Civil War and the stress of being one of the few Union families in the county, they remained in the Batesville area. On May 3, 1862, Union forces under General Samuel Curtis appeared in Batesville; by the end of June, the troops had moved on, leaving the area under Confederate control. About this time, Bliss joined what became known as the First Battalion, Arkansas Union Infantry. He was commissioned a first lieutenant in Company A. The unit was established at Helena. Its members were always in ill health—due to poor food, medical care, and sanitation—and thus saw no combat. By the time they were mustered out in St. Louis, Missouri, at the end of 1862, about 150 of the original 365 men and fourteen officers had died of disease.

By the spring of 1863, conditions in Independence County were becoming dangerous for Union men. Bliss was away when his wife decided it was no longer safe for the family to live in Batesville. She, her two children, her sister Abby, and several other families started north across enemy lines on June 20. Early on, Carrie and daughter Julia became ill, and the party was delayed about ten days. Their route went over the Ozark Mountains and into Missouri, and they eventually reached Rolla, where the railroad began. From there, they went to St. Louis where Carrie and the children stayed about two weeks before continuing on. They finally arrived in Bradford, Maine, where Carrie’s parents lived.

Bliss, meanwhile, was selected as Independence County delegate to the constitutional convention to be held in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in early 1864. Julia died on November 20, 1863, in Maine. Bliss did not get the news for more than a month.

At the convention, the state’s Confederate Constitution of 1861 was rejected and replaced by the 1836 constitution with modifications that made slavery illegal in the state. In the subsequent election in March, Bliss was elected lieutenant governor. President Abraham Lincoln sent several supportive letters to Governor Isaac Murphy’s administration. In 1864, Bliss wrote back about the problems that existed for Union supporters surrounded by so many Confederate supporters, and he assured Lincoln that “the Union element is truly loyal and not in sympathy with the rebels even on the subject of slavery.”

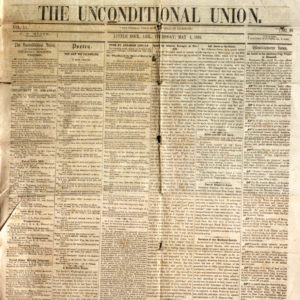

In April 1864, Bliss ventured into publishing, buying an interest in a Little Rock paper, The True Democrat. By early 1865, he was signing correspondences as publisher of the Unconditional Union, replacing the first editors and publishers of the paper.

With the surrender of General Robert E. Lee’s army in April 1865, reuniting his family became a priority for Bliss. In August, he returned to Maine to bring his family back to Little Rock.

In 1866, Bliss went to Washington DC on state business, planning to arrive in time for the “sitting of Congress.” He intended to be gone at least two months, but while he was in Washington, there was a fire at the Unconditional Union that he suspected was arson. He continued as lieutenant governor until the ratification of the 1868 state constitution.

As Arkansas recovered from the war, Bliss strove to improve conditions for former slaves; he wrote to the American & Foreign Bible Society to ask for Bibles and psalm books for them. He continued his real estate and publishing efforts, and the family took in boarders to make ends meet. Bliss’s third daughter, Addie, was born in Little Rock on August 29, 1869.

The family continued to have serious financial problems that were caused primarily by real estate speculation errors, and Carrie’s health started to decline. She died on September 4, 1881, in Little Rock. Within a few years of Carrie’s death, Bliss and the children moved to Sweet Home (Pulaski County), where he grew strawberries and taught school. He died of an apparent heart attack on December 13, 1891, and is buried in Oakland and Fraternal Cemetery in Little Rock.

For additional information:

C. C. Bliss Papers. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

James V. Boone

Fairfax, Virginia

Melissa A. Gibbs

DeLand, Florida

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874

Civil War through Reconstruction, 1861 through 1874 Newspapers during the Civil War

Newspapers during the Civil War Calvin Bliss

Calvin Bliss  Carrie Bliss

Carrie Bliss  Unconditional Union

Unconditional Union

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.