calsfoundation@cals.org

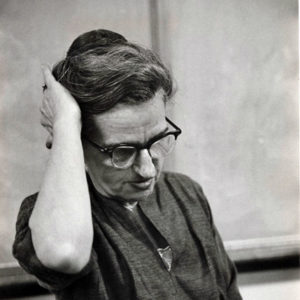

Mary Celestia Parler (1904–1981)

Mary Celestia Parler was responsible for developing and implementing the most extensive folklore research project in Arkansas history. She was a professor of English and folklore at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) and the wife of noted Ozark folklore collector Vance Randolph. Through her vast knowledge and appreciation of Arkansas culture, she enabled many future generations to glimpse the state’s cultural history, much of which remains only in the stories, songs, and images she collected with the help of her students and assistants.

Mary Parler was born on October 6, 1904, in Wedgefield, South Carolina, the daughter of a country doctor and farmer, Marvin Lamar Parler, and a local historian, writer, and teacher, Josie Platt Parler. Mary had one brother, Marvin Lamar Jr., and a sister, Francis Lott, who was actually a cousin adopted by the family at an early age. The family’s three farms grew mainly cotton.

Parler was schooled in Wedgefield until the tenth grade, when she took an early placement exam and was admitted to Winthrop College in Rock Hill, South Carolina. She graduated in 1924 with a BA in English literature and went on to the University of Wisconsin, where she began a lifelong study of Geoffrey Chaucer and earned an MA in English in 1925. She did more graduate work at the University of South Carolina, the University of North Carolina, and at Brown and Columbia universities.

Parler arrived at UA in 1948 while working on a dissertation for the University of Wisconsin on southern dialects, based on the works of William Gilmore Simms. She had a strong background in English literature and had begun dialect work as part of a graduate minor in comparative linguistics while at the University of Wisconsin. She began teaching folklore and Chaucer in the UA English department, where she became known to her students as “Miss Chaucer.” When asked how a Chaucer scholar came to be so interested in Arkansas folklore, Parler commented, “It is perhaps in exploring the intricacies of human behavior that Chaucer and Arkansas folklore are relatable,” and that “there’s a good deal of folklore in Chaucer.”

During her first year in Fayetteville, she was asked to help found the Arkansas Folklore Society, and she served as its secretary-treasurer from 1950 to 1960 and later as the society’s archivist and as a member of its Council of Members. She recommended the creation of a society newsletter, and much of the folklore collected and reported by the group appeared there, making up a large part of the University of Arkansas Folklore Collection.

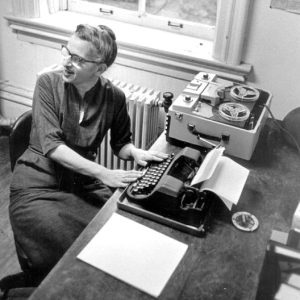

In 1949, she developed UA’s first folklore course, became director of the University of Arkansas Folklore Research Project, and began compiling the archival material with the help of her field assistant, Merlin Mitchell. The collection of folksongs includes 442 reels (137,400 feet) of audiotape with full transcriptions, making it one of the largest collections of its kind.

Collected over fifteen years, these recordings include many “event” ballads native to Arkansas, a Cherokee choir singing Baptist hymns, songs collected from immigrants, fiddle tunes, jokes, and tales. The collection of English language ballads includes both those written in this country as well as those that came over from the British Isles, the written forms of which can be traced to the thirteenth century.

As a folklorist, Parler understood the cyclical nature of folklore but also believed that traditional culture was threatened by the rapid expansion of towns and cities, and from developing technologies such as radio and television. She was unusual in having the foresight to look beyond strictly traditional forms and preserve “original” songs written by her informants (those who supplied cultural information to her), as well as Ozark versions of early commercial country music adapted from tradition by performers such as the Carter Family. This was innovative collecting, perhaps influenced by her future husband and collaborator, the preeminent Ozark folklorist Vance Randolph.

Many at the time believed she would have a hard time collecting anything, even suggesting she would come up empty handed. She just laughed. She returned from her first trip in September 1953 with eighteen songs recorded from Virgil Lance of Mountain Home (Baxter County). Ultimately, her collection comprised 3,640 songs.

She collected more than just folksongs. Stored in the University Libraries’ Special Collections department is an unprocessed collection of 60,000 handwritten note cards of “Ozark-isms” collected by Parler, her assistants, and her students. They include eighteen volumes of typescript citations composed of eleven volumes of folk beliefs and superstitions, four of proverbs, two of riddles, and one of ballads and songs.

In 1954, CBS television made Parler’s collecting the focus of an episode of the program The Search. The episode centered on her search for “the great-great-grandchild” of an Elizabethan ballad, “The Two Sisters.”

The first collaboration between Vance Randolph and Parler took place in 1953, when they worked together on Randolph’s dialect book, Down in the Holler: A Gallery of Ozark Folk Speech. She also assisted Randolph with his later books, The Talking Turtle (1957) and Hot Springs and Hell (1965). A flirtation that had begun at Arkansas Folklore Society meetings in 1950 led to their wedding in the spring of 1962. The marriage certificate is dated March 27, 1962, but there is no account of a ceremony. They had no children. Though Parler legally assumed the last name of her husband, she continued professionally under her maiden name.

In 1963, Parler published her only book, Arkansas Ballet Book, a compilation of Ozark ballads she had collected from informants over the years. In 1972, she was made professor emerita, and she retired from UA in 1975, having taught half-time for the previous three years. She returned to South Carolina shortly after Randolph died in 1980, and she died there less than a year later on September 15, 1981. She is buried at the Church of the Holy Cross in Stateburg, South Carolina, alongside her mother and father.

The work of Parler was revisited in 2005 when the University Libraries’ Special Collections department hosted a two-day conference, “A Collector in Her Own Right: Reassessing Mary Celestia Parler’s Contribution to Ozark Folklore.” The conference brought together collectors, scholars, and former students of Parler to discuss her life and work.

For additional information:

Mary Celestia Parler Research Materials. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Mary Celestia Parler Vertical File. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Nelson, Sarah Jane. Ballad Hunting with Max Hunter: Stories of an Ozark Folksong Collector. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2023.

Reynolds, Rachel. “Mary Celestia Parler (1904–1981): Folklorist and Teacher.” In Arkansas Women: Their Lives and Times, edited by Cherisse Jones-Branch and Gary T. Edwards. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018.

———. “Mary Celestia Parler Randolph: ‘Gladley Wolde She Lerne and Gladley Teche.’” Overland Review 31 (2003).

———. “Mary Celestia Parler Randolph, Collector of Arkansas Folklore and Dedicated U of A Teacher.” Flashback 72 (Spring 2022): 28–38.

Rachel Reynolds Luster

Coalition for Ozarks Living Traditions

Mary Parler

Mary Parler  Mary Parler

Mary Parler

I was fortunate enough to be her student, and fortunate enough to collect a song which told of the Berryville jail burning down with its occupants inside. I got it from the lawyer Melvin Anglin, the father of a college friend of mine. The problem was, I had to sing it in front of the class. I pretty much made a tuneless dirge of it and was seldom more embarrassed in my college career. And that’s saying a lot.