calsfoundation@cals.org

Baitfish Industry

Arkansas leads the nation in the farming of bait and feeder fish, providing sixty-one percent of the value of all cultured baitfish in the country. Baitfish are small minnows used as fishing bait to catch predatory game fish such as crappie, catfish, walleye, and largemouth bass. Feeder fish are small fish sold as live food for fish and animals in aquariums and zoos. Six billion bait minnows—predominantly golden shiners, fathead minnows, and goldfish—are raised in Arkansas each year and shipped throughout the country. In 1998, the Census of Aquaculture recorded sixty-two baitfish farms in Arkansas. The annual farm-gate value of Arkansas baitfish production was $23 million; with an economic impact of six to seven times this amount, baitfish production contributes significantly to the economies of Lonoke, Prairie, Monroe, and Greene counties, where most of these fish are raised. The vast majority of baitfish cultured in Arkansas are shipped to other states for retail sale.

In the 1930s, before the advent of baitfish farming, essentially all the minnows used for bait were captured from the wild. Even today, it is estimated that forty to fifty percent of baitfish sold in the United States are wild fish removed from natural ecosystems. Along with taking fish for bait, harvesters may accidentally remove other fishes or even exotic species and unintentionally spread them to new water bodies. Bait-bucket transfer has been implicated as the source of over 100 introductions of fish species to new environments. In contrast, baitfish farming provides a renewable supply of healthy, quality minnows of a few select species that are already widely distributed.

The demand for live fish as bait increased in the decades after World War II as fishing became an increasingly popular form of recreation and as new reservoirs created for flood control, irrigation, and hydroelectric power provided additional fishing opportunities. The first baitfish farms appeared in Arkansas in the mid-1940s; in 1952, there were 536 acres in baitfish production. By 1972, the state had 29,061 acres of production ponds. Acreage declined after the 1970s as farmers intensified production on fewer acres. In the early twenty-first century, Arkansas had an estimated 24,000 acres of baitfish ponds. Many are visible to air travelers as they approach Little Rock (Pulaski County) from the east. All baitfish farms in Arkansas are family operations or partnerships, and the vast majority are small businesses.

Arkansas’s role

Arkansas became the center of baitfish production through the juxtaposition of appropriate physical factors—such as abundant land with water-holding soils, sufficient water, favorable climate, and transportation facilities—and innovative fish farmers. Early pioneers such as I. F. (Fay) Anderson, Harry Saul, Tony Carruth, Euell Nixon, Bob Treadway, Ralph Norris, Malcolm Johnson, Ruben Pool, Roy Prewitt, and others developed the culture methods and the markets for farm-raised baitfish. The golden shiner occurred naturally in the waters of Bayou Meto, and this species was found to adapt well to pond culture techniques.Through trial and error, these early producers developed the basis for the current industry. In the early years, the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife (now the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) Fish Farming Experimental Station in Stuttgart (Arkansas County) provided technical support to fish farmers. This station was developed as a result of the 1958 Fish-Rice Rotation Farming Program Act.

Technological advances

A major technological revolution occurred in baitfish farming in the late 1990s with the adoption of tank hatching of baitfish eggs. Previously, farmers had moved mats with eggs directly to grow-out ponds for incubation and culture. Resulting production was often low and variable as most eggs were lost to fungus infestations, and research showed that in some cases eggs were exposed to suboptimal dissolved oxygen conditions. Dr. Eric Park, an industry consultant, worked with Danny Pool of Pool Fisheries and James Neal Anderson of Anderson Minnow Farm to develop the first commercial hatcheries. Tank hatching had been proposed first by University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff (UAPB) researchers in 1989, and over time conditions in the industry had changed sufficiently to make this feasible. Today, most baitfish eggs are hatched in indoor hatcheries.

Production cycle

The baitfish farming production cycle begins in the spring as adult brood fish are spawned. In nature, golden shiners and goldfish spawn in groups and lay adhesive eggs on vegetation, so farmers substitute mats made from coconut fibers to serve as egg collectors. The egg-laden mats are transferred to indoor hatcheries, where the eggs are incubated in clean, oxygenated water. After they hatch, the baby fish (fry) are moved to earthen ponds. Ponds for golden shiners are usually five to twenty acres, while goldfish are often raised in smaller ponds, typically two acres. Fry are stocked at rates from 100,000 to two million per acre, depending on the size of fish desired. Fathead minnows reproduce differently. The male fathead selects and defends a nest site on the underside of a submerged object, and the eggs are laid on the “ceiling.” Resulting fry are raised together with the adult fish, at least until they become large enough to transfer to other ponds.

During the summer, fish farmers care for their growing crops. Fish are fed daily with prepared diets, typically in the form of extruded floating pellets containing twenty-eight or higher percent crude protein and made mostly from soybean meal, cottonseed meal, and other plant products. The form of the feed is varied according to the size of the fish; fry are fed a fine powder (meal), young fish are fed “crumbles” (feed pellets broken into bits), and larger fish are fed intact pellets. Fish also consume natural foods available in ponds, such as zooplankton and insect larvae. Pond water quality is checked regularly, and many farmers use aerators to ensure that the fish have sufficient nighttime concentrations of dissolved oxygen. Aquatic weeds must be controlled, levees mowed, and predatory birds scared away. Wading birds in particular are a major source of fish loss. Farmers also monitor fish health; if problems are suspected, a sample of fish and water is taken to the UAPB fish health laboratory in Lonoke (Lonoke County). Many farmers also participate in a voluntary farm-level fish health certification program.

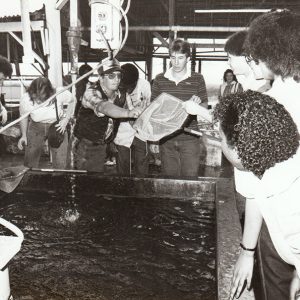

As fish reach market size, farmers harvest them over time by placing sinking feed into a corner of the pond as bait. When fish gather to feed, they are surrounded with a fine mesh net (seine) and captured. Buckets of fish and water are loaded into a hauling tank and taken to a minnow shed. At the shed, fish are unloaded into holding vats—shallow concrete tanks with clean, aerated water. Salt is added to reduce fish stress, and fish are left undisturbed for about twenty-four hours to allow them to “harden” or acclimate to vat conditions. Farmers then separate the fish into size categories by pulling various graders through the vats. The graders contain panels with evenly spaced parallel bars; the distance between the bars is in units of one-sixty-fourth of an inch. After grading, fish are ready for market. Baitfish are usually shipped to market by truck, in special hauling rigs equipped with tanks supplied with oxygen. Feeder fish often are shipped by air, in plastic bags with oxygen, protected by insulated boxes.

Economic impact

Marketing is critical to a baitfish farm. Farmers provide baitfish of different sizes year-round to meet angler demands. Large minnows are used for bass and hybrid striped bass fishing, while small minnows are popular as crappie bait. The retail demand for baitfish fluctuates and depends on many factors outside the producer’s control, such as the weather. A warm winter will mean a short ice fishing season and reduced baitfish sales; similarly, a rainy July 4 weekend will hurt business. Astute producers monitor weather forecasts for their market regions to estimate potential orders so they can have an adequate supply of minnows harvested and ready for sale. It has been estimated that retail sales of baitfish in the United States and Canada total about one billion dollars a year. As is the case with many agricultural products, the producer sees only a fraction of the value. Retail prices are ten to fifteen times higher than those obtained by farms, and cultured baitfish face continued competition from relatively inexpensive wild baitfish, even though the farmed product is widely acknowledged to be superior.

The baitfish industry provides employment and generates economic activity in Arkansas. Feeds for baitfish are made with Arkansas-grown soybean meal, rice bran, and cottonseed meal. Feed mills in Dumas (Desha County) and North Little Rock (Pulaski County) are major suppliers to the industry. Live-hauling companies that transport baitfish have grown with the industry, and aquaculture supply houses provide everything from spawning material to waders. Investment capital has gone into building new hatcheries and holding sheds. Labor requirements are higher in baitfish farming than for catfish production, and skilled labor is in demand given the current technical sophistication of the hatcheries.

Management practices

Over the years, baitfish farmers have sought to reduce water use and minimize effluent from ponds. Farmers will recycle water when emptying a pond by pumping it into another pond rather than opening the drain. The new hatchery systems have reduced the number of required nursery ponds (ponds that must be drained before stocking) so that an increased percentage of the ponds on a farm can remain in production for years without draining. In 2002, the Arkansas Bait and Ornamental Fish Growers Association published “Best Management Practices for Bait and Ornamental Fish Farms” for members to further minimize potential negative environmental effects from their farms. Similarly, the association developed a publication on fish farm biosecurity to help farmers avoid fish disease or aquatic nuisance species hazards. By 2006, the association was working with the Arkansas Department of Agriculture to develop a voluntary quality assurance program for farm-raised baitfish so that Arkansas baitfish farmers can continue to supply the nation with “Quality Bait from the Natural State.”

For additional information:

Aquaculture/Fisheries Center at University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Online at http://www.uapb.edu/academics/school_of_agriculture_fisheries_and_human_sciences/aquaculture_fisheries/aquaculture_fisheries.aspx (accessed August 10, 2023).

Bell, Robert. “History of U.S. Aquaculture Has Roots in Arkansas.” Arkansas Business. August 30, 2010–September 5, 2010, pp. 1, 14, 16.

Clements, Stephen. “Foraging Ecology and Depredation Impact of Scaup on Commercial Baitfish and Sportfish Farms in Eastern Arkansas.” MS thesis, Mississippi State University, 2019. Online at https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td/2319/ (accessed August 10, 2023).

Dorman, Larry W. “Baitfish Production in Arkansas: a Historical Review.” Proceedings of the North Central Aquaculture Conference 91 (1991): 231–236.

Lochmann, Rebecca T., Nathan Stone, and Eric Park. “Baitfish Feeds and Feeding Practices.” Southern Regional Aquaculture Center 121 (2002). Online at https://freshwater-aquaculture.extension.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Baitfish_feeds_and_feeding_practices.pdf (accessed August 10, 2023).

Stone, Nathan. “Baitfish Culture.” In The Encyclopedia of Aquaculture. Edited by R.R. Stickney. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2000.

Nathan Stone, Larry Dorman, and Hugh Thomforde

Aquaculture/Fisheries Center

University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff

Agriculture

Agriculture Aquaculture

Aquaculture Business, Commerce, and Industry

Business, Commerce, and Industry Anderson Farms Tank

Anderson Farms Tank  Baitfish Vat

Baitfish Vat  Fan-tailed Goldfish

Fan-tailed Goldfish  Joe Hogan Fish Hatchery

Joe Hogan Fish Hatchery  Minnow Brochure

Minnow Brochure  Minnow Harvest

Minnow Harvest  Minnow Harvest

Minnow Harvest  Minnows

Minnows

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.