calsfoundation@cals.org

Sundown Towns

aka: Racial Cleansing

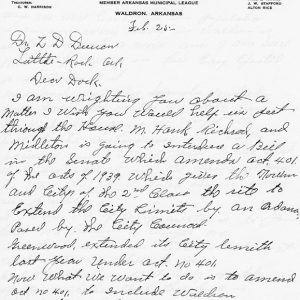

Between 1890 and 1968, thousands of towns across the United States drove out their Black populations or took steps to forbid African Americans from living in them. Thus were created “sundown towns,” so named because many reportedly marked their city limits with signs typically reading, “Nigger, Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On You In Alix”—an Arkansas town in Franklin County that allegedly had such a sign around 1970. By 1970, when sundown towns were at their peak, more than half of all incorporated communities outside the traditional South probably excluded African Americans, including probably more than a hundred towns in the northwestern two-thirds of Arkansas. White residents of the traditional South rarely engaged in the practice; they kept African Americans down but hardly drove them out. Accordingly, no sundown town has yet been confirmed in the southeastern third of Arkansas that lies east of a line from Brightstar (Miller County) to Blytheville (Mississippi County), and only three likely suspects have emerged.

Sundown towns in Arkansas range from hamlets like Alix to larger towns like Paragould (Greene County) and Springdale (Washington and Benton Counties). Entire counties went sundown, such as Boone, Clay, and Polk. Some multi-county areas also kept out African Americans. In Mississippi County, for example, according to historian Michael Dougan, a red line that was originally a road surveyor’s mark defined a “dead line” beyond which African Americans might not trespass to the west. That line apparently continued northeast into the Missouri Bootheel and southwest to Lepanto (Poinsett County), delineating more than 2,000 square miles.

Although there were not towns like these prior to the Civil War, precedents existed for the exclusion of free African Americans. As early as 1843, Arkansas denied free Blacks entry into the state, and in 1859, Arkansas required such persons to leave the state by January 1, 1860, or be sold into slavery. Moreover, in 1864, the loyalist Arkansas faction passed a new state constitution that abolished slavery but excluded African Americans from moving into the state. However, that constitution never went into effect, and during Reconstruction, African Americans participated politically across the state. In 1890, every county had at least six African Americans, and only one had fewer than ten.

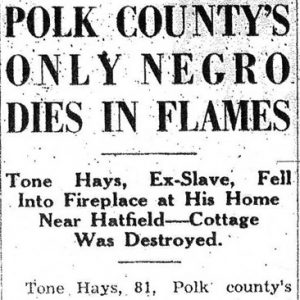

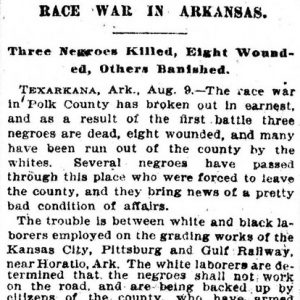

Then, between 1890 and 1940, white residents forced African Americans to make a “Great Retreat” in Arkansas and across the North. During this “Nadir of Race Relations,” lynchings peaked, and unions drove African Americans from such occupations as railroad fireman and meat cutter. Democrat Jeff Davis ran for Arkansas governor in 1900, 1902, and 1904, and then for the U.S. Senate in 1906; his language grew more Negrophobic with each campaign. “We have come to a parting of the way with the Negro,” he shouted. “If the brutal criminals of that race…. lay unholy hands upon our fair daughters, nature is so riven and shocked that the dire compact produces a social cataclysm.” White people responded with violence. By 1930, three Arkansas counties had no African Americans at all, and another eight had fewer than ten, all in the Arkansas Ozarks. By 1960, six counties had no African Americans (Baxter, Fulton, Polk, Searcy, Sharp, and Stone), seven more had one to three, and yet another county had six. All fourteen were probably sundown counties; eight have been confirmed.

Much of this area had been Unionist during the Civil War. Until 1890, white residents had maintained fairly good relations with their small African American populations, partly because African Americans and white non-Democrats were political allies. Then, election law changes and Democratic violence made interracial coalitions impractical. Now, it would not pay to be anything but a Democrat. Allied with this Democratic resurgence, a wave of neo-Confederate nationalism swept Arkansas: most Ozark county histories written after 1890 tell of the war exclusively from the Confederate point of view. More than ever, it was in the interest of white populations to distance themselves from African Americans. Precisely in counties where residents had been Unionists, white residents now often seemed impelled to prove themselves ultra-Confederate and manifested the most robust anti-Black fervor.

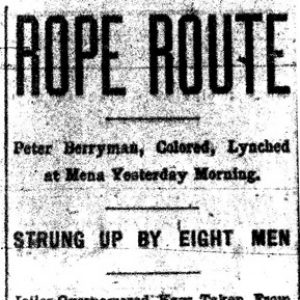

Often, the expulsion of African Americans was forced. Harrison (Boone County), for example, had been a reasonably peaceful biracial town in the early 1890s.”There was never a large Negro population,” according to Boone County historian Ralph Rea, “probably never more than three or four hundred, but they had their church, their social life, and in the main there was little friction between them and the whites.” Then, in late September of 1905, a white mob stormed the jail, carried several Black prisoners outside the town, whipped them, and ordered them to leave. The rioters then swept through Harrison’s black neighborhood, tying men to trees and whipping them, burning several homes, and warning all African Americans to leave that night. Most fled without any belongings. Three or four wealthy white families sheltered servants who stayed on, but in 1909, another mob tried to lynch a Black prisoner. Fearing for their lives, most remaining African Americans left. Harrison remained a sundown town at least until 2002. Similarly, Mena (Polk County) had a small Black population until February 20, 1901, when a mentally impaired African American badly injured a twelve-year-old white girl. A white mob then took him from jail, fractured his skull, shot him, and cut his throat. Many local histories trace the disappearance of the African American population to this event, although the decline of the railroad-based economy likely played a large role.

Some of these riots, in turn, spurred whites in nearby smaller towns to hold their own, thus provoking little waves of expulsions. The Boone County events probably led to ejections from neighboring counties. In the early 1920s, William Pickens reported seeing sundown signs across the Ozarks. By 1930, the region’s total Black population had shrunk to half its pre-Civil War total.

Sundown towns often allowed one or two African Americans to remain, even while posting signs warning others not to stay the night. In Harrison, for example, James Wilson met the 1909 mob at his door with a shotgun and protected his house servant, Alecta Smith. Later, she insisted that her name was Alecta Caledonia Melvina Smith, but she also let white people call her “Aunt Vine,” which played along with the inferior status connoted by “uncle” and “auntie” as applied to older African Americans and helped her survive in an otherwise all-white community. Several Arkansas counties and towns show a slowly diminishing number of African Americans between 1890 and 1940 because they did not allow new Black people in, and those who remained gradually died or left.

Sundown towns have shown astonishing tenacity. In the early 1900s, for example, pioneering archaeologist Clarence Moore “dared not proceed beyond Lepanto” on the Little River, for fear of endangering his Black crew members. Dan and Phyllis Morse note that “race relations remain strained in that region,” a polite way of saying that African Americans still do not and perhaps cannot live safely in that area a century later. Sundown towns have achieved this stability by a variety of means. Some townspeople painted black mules on barns or rock outcrops, signaling to all that no “black ass” was allowed to spend the night. In Mena, African Americans did not even have to stop to get in trouble. Shirley Manning, a high school student there in 1960–61, describes the scene: “The local boys would threaten with words and knives Negroes who would come through town, and follow them to the outskirts of town shouting ‘better not let the sun set on your black ass in Mena, Arkansas,’ and they often ‘bumped’ the car with their bumper from behind. I was along in a car which did this, once, and saw it done more than once.”

An undated newspaper clipping from Rogers (Benton County), probably between 1910 and 1920, tells of the terror that African Americans might encounter in sundown towns even during the day. A Bentonville (Benton County) contractor was building a brick building in Rogers and brought with him a Black hod carrier: “A group of young men were gathered in the Blue saloon when the Negro entered, probably looking for his employer. The group seized the Negro and began telling what they were going to do with him.” They threatened to drop him in an old well in the rear of the construction site after they had hanged him, “but others objected on the ground that the odor from the ones already planted there was becoming objectionable to the neighborhood.” Eventually, they let “the trembling Negro” slip, “and in a matter of seconds, he was just a blur on the horizon.” The incident was meant to be funny, for had the men been serious, they could easily have apprehended the runaway, yet was not entirely in jest, for it accomplished the man’s unemployment, surely one of its aims.

Economic boycott has kept many African Americans out of sundown towns. As motel owner Nick Khan said about Paragould in 2002, “If black people come in, they will find that they’re not welcome here. No one will hire them.” Whites who might defy the ban face reprisals. In 1969, a choir from Southern Baptist College performed in Harrison. One choir member was Black, and a couple put her up for the night, “but we worried lest our house get blown up,” remembered the wife. Despite being warned not to, Khan hired an African American to work at his motel in 1982; his transient clientele gave him a form of economic independence.

Sundown towns continued to form in Arkansas as late as 1954, when white residents of Sheridan (Grant County) rid themselves of their Black neighbors in response to Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. The owner of the local sawmill and the sawmill workers’ homes was principally responsible. He made his African American employees an extraordinary offer: he would give them their homes and move them to Malvern (Hot Spring County), twenty-five miles west, at no cost to them. If a family refused to move, he would evict them and burn down their home. Unsurprisingly, African Americans “chose” to leave. The few other African Americans in Sheridan—preachers, independent business operators—suddenly found themselves without a clientele. They left, too. Afterward, Sheridan developed a reputation for aggressively anti-Black behavior. Some smaller communities in Arkansas may also have gotten rid of their African Americans after Brown.

Hate groups have long been drawn to sundown towns. Harrison developed a large Ku Klux Klan (KKK) chapter that targeted striking railroad workers in the 1920s, hanging one from a railroad bridge in 1923 and escorting the rest to the Missouri line. KKK leaders still live in the Harrison area. Gerald L. K. Smith, a radio evangelist and leading anti-Semite in the 1930s and 1940s, moved his headquarters to Eureka Springs (Carroll County) partly because it was an all-white town.

Historian Patrick Huber calls the expulsions by which Ozark communities became sundown towns “defining events in the history of their communities.” Nevertheless, despite that importance, or rather because of it, most sundown towns have kept hidden the means by which they became and stayed white. Sociologist Gordon Morgan, trying in 1973 to uncover the history of African Americans in the Ozarks, wrote, “Some white towns have deliberately destroyed reminders of the blacks who lived there years ago.” To this day, other than by oral history, sundown towns are hard to research, because communities took pains to ensure that nothing about their policy was written. The Rogers Historical Museum has done an exemplary job of preserving an example of this suppression. In 1962, the Rogers Daily News upset the local Chamber of Commerce by using the following language in a front-page editorial lauding a successful Fats Domino concert: “The city which once had signs posted at the city limits and at the bus and rail terminals boasting ‘Nigger, You Better Not Let the Sun Set On You in Rogers,’ was hosting its first top name entertainer—a Negro—at night!” The chamber called the newspaper editor to task and asked its public relations committee to “keep a close watch on future news reporting and take any appropriate action should further detriment to the City of Rogers be detected.”

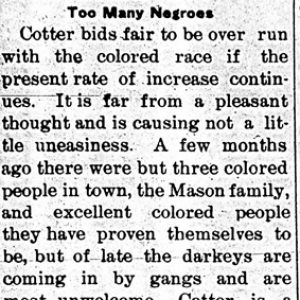

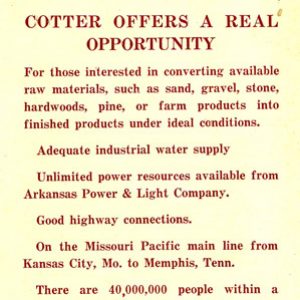

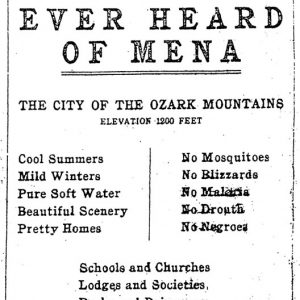

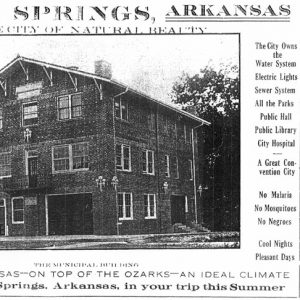

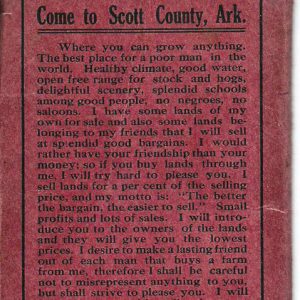

Some Arkansas towns long used their racial composition as a selling point to entice new residents. Mena advertised what it had—“Cool Summers, Mild Winters”—and did not have —“No Blizzards, No Negroes.” In its 1907 Guide and Directory, Rogers competed by bragging about its “seven churches, two public schools, one Academy, one sanitorium” and noted, “Rogers has no Negroes or saloons.” Not to be outdone, nearby Siloam Springs (Benton County) claimed “Healing Waters, Beautiful Parks, Many Springs, Public Library,” alongside “No Malaria, No Mosquitoes, and No Negroes.” The pitch worked: a 1972 survey of Mountain Home (Baxter County) residents found many retirees from Northern cities who chose Mountain Home partly because it was all-white. A reporter in Mena wrote in 1980, “It is not an uncommon experience in Polk County to hear a newcomer remark that he chose to move here because of ‘low taxes and no niggers.’”

For fifteen years after the 1964 Civil Rights Act, motels and restaurants in some sundown towns continued to exclude African Americans. Today, public accommodations are generally open. More than half of all Arkansas sundown towns have given up their exclusionary residential policies, mostly after 1990. Of fourteen suspected sundown counties in 1960, eight showed at least three African American households in the 2000 census. Additional “white” households now include “Black” children, especially interracial offspring of white mothers from the community and Black partners from elsewhere. The public schools of Sheridan desegregated around 1992, when students from two small nearby biracial communities were included in the new consolidated high school. In about 1995, a Black family moved into Sheridan, and before the decade ended, it was joined by three more—slow progress, but progress nevertheless.

Some towns likely still merited the term well into the twentieth century, if not beyond, however. Smokey Crabtree, longtime resident of Fouke (Miller County), wrote in 2001:

As far back as the late twenties colored people weren’t welcome in Fouke, Arkansas to live, or to work in town. The city put up an almost life sized chalk statue of a colored man at the city limit line, he had an iron bar in one hand and was pointing out of town with the other hand. The city kept the statue painted and dressed, really taking good care of it. Back in those days colored people were run out of Fouke, one was even hung from a large oak tree…. As of this date there are no colored people living within miles of Fouke, so the attention getter, the means to shake the little town up isn’t “the Russians are coming,” it’s someone is importing colored people into town.

Moreover, the reputation of sundown towns can be self-sustaining. “Never walk in Greenwood or you will die,” a Black Arkansas college student said in 2002. At the time, however, the 2000 census showed two African-American households in the community.

In 2025, news broke about a planned all-white intentional community located in Sharp County just outside Ravenden (Lawrence County). Called Return to the Land, the community was founded by Eric Orwoll, a classically trained French horn player who was a member of the Shen Yun orchestra and had previously earned money as a performer in pornographic videos, and Peter Csere, a jazz pianist accused of attempted murder and theft in Ecuador. The two men bought land in the area in 2023 with the goal of creating a private community restricted to people of ostensible European heritage and heterosexual orientation. Although most legal scholars predicted that such an enterprise could not withstand legal challenges, the planned community nonetheless indicates that the sundown town remains an ideal for some white Americans.

For additional information:

Anthony, Michael. “Otherwise, You Will Have to Suffer the Consequences: The Racial Cleansing of Catcher, Arkansas.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2023. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/4834/ (accessed October 23, 2023).

Crabtree, Smokey. Too Close to the Mirror. Fouke, AR: Days Creek Production, 2001.

Dougan, Michael. Arkansas Odyssey: The Saga of Arkansas from Prehistoric Times to Present. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1994.

Froelich, Jacqueline. “Race, History, and Memory in Harrison, Arkansas: An Ozarks Town Reckons with Its Past.” In Race and Ethnicity in Arkansas: New Perspectives, edited by John A. Kirk. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2014.

Froelich, Jacqueline, and David Zimmerman. “Total Eclipse: The Destruction of the African American Community of Harrison, Arkansas, in 1905 and 1909.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Summer 1999): 131–159.

Harper, Kimberly. White Man’s Heaven: The Lynching and Expulsion of Blacks in the Southern Ozarks, 1894–1909. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2010.

Jaspin, Elliot. Buried in the Bitter Waters: The Hidden History of Racial Cleansing in America. New York: Basic Books, 2007.

Jones, Catherine Ponder. “Terror at Night.” Lawrence County Historical Journal (2017, no. 2): 5–26.

Kamin, Debra. “The Founders of This New Development Say You Must Be White to Live There.” New York Times, August 19, 2025. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/08/19/realestate/arkansas-white-housing-return-to-land.html (accessed August 25, 2025).

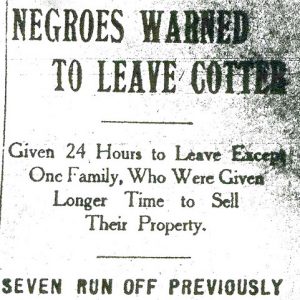

Lancaster, Guy. “The Cotter Expulsion of 1906 and Limitations on Historical Inquiry.” Baxter County History 38 (April, May, June 2012): 26–29.

———. “‘Negroes Are Leaving Paragould by Hundreds’: Racial Cleansing in a Northeast Arkansas Railroad Town.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 41 (April 2010): 3–15.

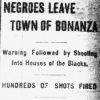

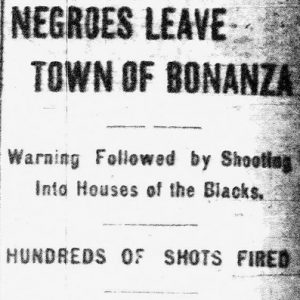

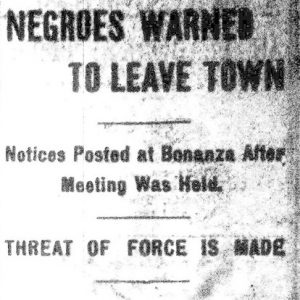

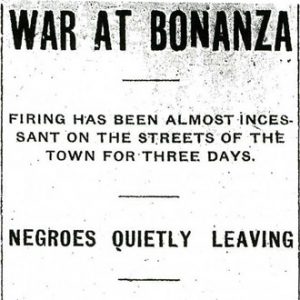

———. “‘Negroes Warned to Leave Town’: The Bonanza Race War of 1904.” Journal of the Fort Smith Historical Society 34 (April 2010): 24–29. Online at https://www.academia.edu/237967/_Negroes_Warned_to_Leave_Town_The_Bonanza_Race_War_of_1904_ (accessed May 10, 2022).

———. “Nightriding and Racial Cleansing in the Arkansas River Valley.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 72 (Autumn 2013): 242–264.

———. “‘…or Suffer the Consequences of Staying’: Terror and Racial Cleansing in Arkansas.” In Historicizing Fear: Ignorance, Vilification, and Othering, edited by Travis D. Boyce and Winsome Chunnu. Louisville: University Press of Colorado, 2019.

———. Racial Cleansing in Arkansas, 1883–1924: Politics, Land, Labor, and Criminality. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2014.

———. “‘There Are Not Many Negroes Here’: African Americans in Polk County, Arkansas, 1896–1937.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 70 (Winter 2011): 429–449.

———. “‘They Are Not Wanted’: The Extirpation of African Americans from Baxter County, Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 69 (Spring 2010): 28–44.

Loewen, James W. Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism. New York: The New Press, 2005.

———. “Sundown Towns and Counties: Racial Exclusion in the South.” Southern Cultures 15 (Spring 2009): 22–47.

Morgan, Gordon D. Black Hillbillies of the Arkansas Ozarks. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Department of Sociology, 1973.

Nichols, Cheryl Griffith. “Pulaski Heights: Early Suburban Development in Little Rock, Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 41 (Summer 1982): 129–145.

Pickens, William. “Arkansas—A Study in Suppression.” In These “Colored” United States: African American Essays from the 1920s, edited by Tom Lutz and Susanna Ashton. New Brunswick, CT: Rutgers University Press, 1996.

“Sundown Towns.” History and Social Justice. https://justice.tougaloo.edu/sundown-towns/ (accessed May 10, 2022).

Rea, Ralph R. Boone County and Its People. Van Buren, AR: Press-Argus, 1955.

“The Real Polk County.” The Looking Glass: Reflecting Life in the Ouachitas 5 (January 1980): 16.

Research Collection. Rogers Historical Museum, Rogers, Arkansas.

Robles, Josh. “Amity’s Lost Black Community.” Clark County Historical Journal 33 (2006): 8–16.

Shiloh Museum of Ozark History. Springdale, Arkansas.

James Loewen

Catholic University of America

My brother recently moved to Arkansas. He wanted to find a more conservative community. He tells me he’s not racist and that his community is not racist…even though the history and current stats would suggest they’re probably ignorant of the ways in which they are racist. I think what my brother means is more like bias, that he might believe there is nothing inherently wrong with people of color, and nothing inherently superior about white people, but he wouldn’t want his children to marry a person of color and he wouldn’t want to support the causes of people of color.

I’m hoping to visit him sometime and invite him to join me in attending a historically Black church on Sunday.

I was born in Rogers, Arkansas, in 1954. My dad graduated from Baylor Dental School in 1950 and started his practice in Rogers. He moved his practice to Texarkana, Arkansas, in 1963. I have so many questions I would like to ask my parents regarding race and about whether this was an underlying reason for living in Rogers, as to my knowledge, no blacks lived there at the time. But, I will say that I never witnessed black slander in our household. At the age of 70, I’m learning lots of concerning things about my beloved state of Arkansas that I’m not proud of. I have been a resident of NW Louisiana for 50 years, but I will always consider Arkansas home. The sundown towns listed were all eye-openers, except for Mena and Harrison. It’s very appalling and sad to me.

I lived in Columbia County during my childhood and most certainly felt the racism often. It may be 2023, but Magnolia feels like 1919!

(2010) I live in Sheridan; I am white and my husband is black. At the Wal-Mart in Sheridan, some customers will not let the black workers check them out. My husband and I get looked at, and I get called a Negro lover. A supervisor of mine at work also told me what they do to Negroes and how they get rid of their bodies. I just ignored him. My husband and I enjoy living in this town, but people still act like whites run the town. My husband doesn’t work because we don’t trust daycare just because of what we are told. We stay to ourselves and don’t eat out because we don’t trust what they would do to the food. At a local restaurant before my husband was handed his food, we watched as the cook put a mop on his head and started saying slangs. That was the first and last time we went out to eat.

We moved to Winslow, Arkansas, from Washington DC in 1977. I was a seventh-grade student, and the first thing I noticed was that we were all white. In fact, my Jewish/Native American mother was the closest thing to a minority they had in this small town. Our eighth-grade history project involved removing many layers of billboard ads off an old billboard to reveal a sundown-town sign. This was a chilling sign to a young girl who was raised around African Americans and truthfully educated with many black people. The “N word” was not used in my house. What was more chilling to me was that my study partner said to me that everyone not only knew about the sign, but just because it was covered didn’t mean it wasn’t still in place. The only reason my mom wasn’t chased out of town was that she was considered my dad’s “squaw.” This billboard stood covered, but people knew it was there until 2000 when it burned and was replaced by a sturdier billboard.

I came across the slogan, “Nigger, don’t let the sun go down on you here,” in the novel West with Giraffes. I was shocked by it – never heard it before. That tells about me: I’m eighty-two and fairly well read, yet never saw this slogan before. I am ashamed of my puny understanding of white supremacy, hatred, and and ignorance. Thank you for this research that broadened my perspective.