calsfoundation@cals.org

Rohwer Relocation Center

The Rohwer Relocation Center in Desha County was one of two World War II–era incarceration camps built in the state to house Japanese Americans from the West Coast, the other being the Jerome Relocation Center (in Chicot and Drew counties). The Rohwer relocation camp cemetery, the only part of the camp that remains, is now a National Historic Landmark. The camp housed, along with the Jerome camp, some 16,000 Japanese Americans from September 18, 1942, to November 30, 1945, and was one of the last of ten such camps nationwide to close. The Japanese American population, of which sixty-four percent were American citizens, had been forcibly removed from the west coast of America under the doctrine of “military necessity” and incarcerated in ten relocation camps in California and various states west of the Mississippi River. This marked the largest influx of any racial or ethnic group in the state’s history.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and America’s subsequent entry into the war, many Americans feared an eventual invasion of the West Coast by the empire of Japan. Many people viewed the Japanese American population—eighty-nine percent of which lived in Washington, Oregon, and California—as potential spies and saboteurs. Citing the “doctrine of military necessity,” President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, giving the secretary of war the power to designate military areas from which “any or all persons may be excluded” and authorizing military commanders to initiate orders they deemed advisable to enforce such action.

On March 18, 1942, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9102, which created the War Relocation Authority (WRA) for the relocation, maintenance, and supervision of the Japanese American population. The search for sites for America’s first Japanese “relocation centers,” as they were euphemistically labeled by the WRA, was limited to federally owned lands located “a safe distance from strategic works,” near railway lines for the easy transport of prisoners, and capable of adequately holding 5,000 to 8,000 people under supervision. By June 4, 1942, the WRA had selected ten sites, with the Arkansas camps being the easternmost of all those incarcerating the Japanese Americans.

The Arkansas sites, situated in the marshy delta of the Mississippi River’s floodplain, were acquired with the assistance of Arkansas’s Farm Security Administration (FSA) chief, Eli B. Whitaker, having originally been tax-delinquent lands in dire need of clearing, leveling, and drainage. Survey descriptions of these lands indicate that Kelso Farms, an Arkansas Corporation subject to a mortgage fee held by the federal government, owned 7,582 acres of the Rohwer site. Another 10,161 acres of land allotted to the Rohwer Center were located twelve miles northeast of McGehee (Desha County), of which 9,560 acres were obtained from the FSA.

Construction on the Arkansas centers began in late July 1942 and extended into January of the next year, almost three full months after most Japanese had arrived. Under the guidance of the Army Corps of Engineers, major building contracts were let to the Linebarger-Senne Construction Company of Little Rock (Pulaski County). Construction cost for the Rohwer camp was $4,800,558.00. The Rohwer site eventually became 500 acres of tarpapered, A-framed buildings arranged into specifically numbered blocks. Each block was designed to accommodate around 300 people in ten to fourteen residential barracks, with each barrack (20’x120′) divided into four to six apartments for Japanese American families. Each block also consisted of a mess hall building, a recreational barrack, a laundry, and a communal latrine. The residential buildings were without plumbing or running water, and the buildings were heated during the winter months by wood or coal stoves. The camp also had an administrative section or block of buildings to handle camp operations, a military police section, a hospital section, a warehouse and factory section, a residential section of barracks for WRA personnel, barracks for schools, and auxiliary buildings for such things as canteens, motion pictures, gymnasiums, auditoriums, motor pools, and fire stations. The camp itself was surrounded by barbed wire or heavily wooded areas with guard towers situated at strategic areas and guarded by a small military contingent.

The internment camp was officially declared open but not completed on September 18, 1942, and would operate under the direction of Project Director Ray D. Johnston. Its peak population reached 8,475 people. Generational divisions of the Japanese American population are as follows: first-generation Japanese nationals were called Issei were precluded from citizenship by federal immigration laws; second- and third-generation Japanese (Nisei and Sansei, respectively) were both American citizens by birth in the U.S. American citizens of Japanese descent who had received some formal education in Japan were referred to as Kibei.

Accurate population and age statistics were constantly changing due to the forced movement of the Japanese populations. Well over ninety percent of the adult Rohwer population of 8,475 had been involved in agriculture, commercial fishing, or businesses that centered on the distribution of agricultural products. Thirty-five percent of the camp’s population was Issei, ten percent of whom were over the age of sixty. Sixty-four percent were Nisei, with forty percent of those under the age of nineteen. There were 2,447 school age children in the camp—a full twenty-eight percent of the total population.

Effective on October 1, 1942, the WRA initiated a new, comprehensive “leave” or “resettlement” program for the incarcerated Japanese Americans in the ten relocation centers, allowing some to live in relative freedom just outside the camp. All classifications of leaves were subject to specific conditions, guidelines, and security checks that could be denied or revoked at any time. The WRA’s leave and resettlement program was met with limited success; each month less than 100 young, college-bound or well-educated, security free, and socially accepted Japanese Americans at Rohwer were able to clear the elaborate process and earn the privilege to leave the camp.

Rohwer was the last of all the WRA camps to close, except for Tule Lake in California. The WRA had a difficult time relocating Japanese Americans back to their old homes and jobs in California. Following their removal, the buildings left behind were used for local schools and by farmers for a variety of purposes before falling into ruin. The Rohwer National Historic Landmark, added to the National Register of Historic Places on July 30, 1974, contains several monuments made by inmates during their internment, including one that honors Japanese American youth who died fighting for America in World War II, a small cemetery, and the remnants of the hospital smokestack.

Among the noteworthy internees at Rowher were George Takei, who went on to become an actor on screen and stage; Nami Shingu, whose family attracted attention for their truck farming efforts; Ruth Asawa, an internationally known artist and advocate for arts education; and artist Henry Sugimoto, whose paintings explored internment and Japanese American identity. Joseph Boone Hunter, a former missionary to Japan, served as the Director of Human Services at the camp, while Nat Griswold was the superintendent of the Community Activities Section, and Jamie Vogel taught art to internees.

In 2012, students of the Arkansas State University Heritage Sites program completed the Rohwer Japanese-American Relocation Center Interpretive Project. Using funds from a National Park Service grant, students of the program developed a walking tour of Rohwer, which includes historical interpretive panels, kiosks, and an audio presentation narrated by George Takei. An informational brochure was also developed for the site. An internment camp museum opened in McGehee in 2013. The following year, the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UA Little Rock) received a grant from the National Park Service to restore and preserve headstones at the Rohwer site.

For additional information:

Anderson, William G. “Early Reaction in Arkansas to the Relocation of Japanese in the State.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 23 (Autumn 1964): 196–211

Bearden, Russell E. “The False Rumor of Tuesday: Arkansas’s Internment of Japanese-Americans.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 41 (Winter 1982): 327–339.

———. “Life Inside Arkansas’s Japanese American Relocation Centers.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 47 (Summer 1989): 170–196.

Daniels, Roger. Concentration Camps: North America. Malabar, FL: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Co. Inc., 1981.

Howard, John. Concentration Camps on the Home Front: Japanese Americans in the House of Jim Crow. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Imahara, Walter M, and David E. Meltzer, ed. Jerome and Rohwer: Memories of Japanese American Internment in World War II Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2022.

Life Interrupted: The Japanese American Experience in WWII Arkansas. https://ualr.edu/cahc/tag/life-interrupted/ (accessed July 6, 2023).

Moufdi, Ismail. “Comparing and Contrasting the Construction of Identity by Residents of Dyess Colony and the Rohwer Resettlement Camp.” PhD diss., Arkansas State University, 2021.

Rohwer Japanese American Relocation Center. http://rohwer.astate.edu/ (accessed July 6, 2023).

“Rohwer Relocation Center Site.” National Register of Historic Places nomination form. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Rohwer Restored: Documenting the Restoration of the Cemetery at Rohwer Relocation Center. University of Arkansas at Little Rock Center for Arkansas History and Culture. http://ualrexhibits.org/rohwer/ (accessed April 30, 2020).

Rohwer Reconstructed: Interpreting Place through Experience. Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. https://risingabove.cast.uark.edu/ (accessed July 6, 2023).

Rosalie Santine Gould–Mabel Jamison Vogel Collection. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Schiffer, Vivienne. “Legacies & Lunch: Camp Nine.” October 5, 2011. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas. Audio online at Butler Center AV/AR Audio Video Collection: Vivienne Schiffer Lecture (accessed July 6, 2023).

Schneider, Jane. “Ending the Silence.” Memphis Magazine, February 2003. http://memphismagazine.com/features/ending-the-silence/ (accessed July 6, 2023).

Steed, Stephen. “Return to Rowher [sic].” Spectrum Weekly, July 8–14, 1992, pp. 8–11.

Time of Fear. VHS, DVD. PBS Home Video, 2004.

Ziegler, Jan Fielder. “Listening to ‘Miss Jamison’: Lessons from the Schoolhouse at a Japanese Internment Camp, Rohwer Relocation Center.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 33 (August 2002): 137–146.

———. The Schooling of Japanese American Children at Relocation Centers During World War II: Miss Mabel Jamison and Her Teaching of Art at Rohwer, Arkansas. Lewiston, NY: The Mellen Press, 2005.

Russell E. Bearden

White Hall, Arkansas

Military

Military Politics and Government

Politics and Government Rohwer (Desha County)

Rohwer (Desha County) World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Camp Shelby Dance

Camp Shelby Dance  Joseph Hunter, portrait by Henry Sugimoto

Joseph Hunter, portrait by Henry Sugimoto  Japanese American Enlistees at Rohwer

Japanese American Enlistees at Rohwer  Japanese American Internment Museum

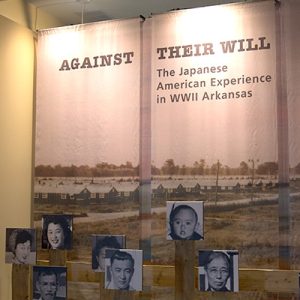

Japanese American Internment Museum  Japanese American Internment Museum Display

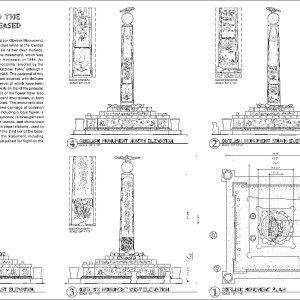

Japanese American Internment Museum Display  Rohwer Monument Plans

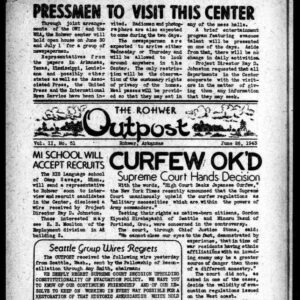

Rohwer Monument Plans  Rohwer Outpost

Rohwer Outpost  Rohwer Relocation Center

Rohwer Relocation Center  Rohwer Aerial View

Rohwer Aerial View  Rohwer School

Rohwer School  Rohwer Memorial

Rohwer Memorial  Rohwer Marker

Rohwer Marker  Rohwer Memorial

Rohwer Memorial  Rohwer Relocation Center

Rohwer Relocation Center  George Takei

George Takei  Jamie Vogel

Jamie Vogel

I’ve met a couple of people who were interned at Rohwer and Jerome. Although I am a Fayetteville native, I now live in San Francisco and am a minister’s assistant at the Buddhist Church of San Francisco, a Jodo Shinshu Buddhist temple and the national temple of the primarily Japanese-American Buddhist Churches of America. Many of our members spent part of their childhoods or their young adult years in the camps throughout the country. It’s not at all unusual to hear older members, meeting others for the first time, ask where their families were interned. From there, connections are made when they realize their uncle or their mother knew so-and-so’s sister or cousin at Tule Lake or Manzanar or Rohwer or Jerome. A few times now when people have asked where I’m from, they’ve told me about their experiences in Arkansas, or mentioned that friends of theirs had been interned there. In each case, I believe, they add that they’ve never been back. Thats not hard to imagine. As a ministers assistant, I conduct worship services in an assisted-living home for seniors, the vast majority of whom are Japanese American. Those who experienced the camps are old now and are dying off. Many of our temples members have told me about their experiences in the camps and about their struggles to rebuild their lives after they were freed. Im grateful they thought enough of me to share their stories.

My parents were Southern Baptist missionaries to Japan in 1934 and 1935. After my father’s repatriation from internment in Tokyo after Pearl Harbor (my mother and sister had returned earlier), my parents served with Japanese-speaking congregations, first in Houston and then in Arkansas, his home state. They lived in McGehee, between the centers at Rohwer and Jerome, until their landlady sold the house from under them. At this point, the U.S. government contacted my mother, asking if she would teach third grade at Rohwer. She demurred, first on the grounds that she was certified for secondary and not elementary teaching, and then because she was pregnant and would not be able to finish the year. They were desperate, so they got a teacher and my family got a home. I was born in the camp clinic on April 23, 1945contrary to some information I have seen saying the camp was closed prior to that date. [Editors note: The center closed in November 1945.] I have the Red Cross Yearbook for 1945, which includes a group picture of the Rohwer Federated Christian Church Congregation, with my father, W. Maxfield Garrott, fifth from the right on the front row. I have long wondered how many, if any, other Anglo babies were born in the camps.

My mother and her immediate family (Sagara) and my uncle, George Matsuoka, were internees of the Rohwer, Arkansas, Relocation Center. They related a story to us illustrating the humiliation they suffered in the center. One day, the men were organized into a work detail and sent out to gather wood and clear brush outside the wire fence surrounding the camp. At some point, they were gathered up and forced to march down the center of town, where they were taunted and pelted with rocks. This was a pivotal experience in my Uncle Georges life, as he decided from that point on to never allow people to be treated in that manner. He became a champion of human rights in his life and won the admiration of many. Also of note, the Issei farmers in Rohwer included many from the Stockton and Lodi California area. These farmers succeeded in farming the San Joaquin Delta. Many had tried before them and failed. A building is named after George Shima The Potato King on the San Joaquin Delta College campus.