calsfoundation@cals.org

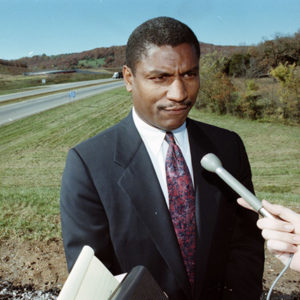

Rodney Earl Slater (1955–)

Rodney Earl Slater rose from poverty to become an Arkansas assistant attorney general and served in several positions under Arkansas governor (and later U.S. president) Bill Clinton. He was chairman of the Arkansas Highway Commission, director of governmental affairs for Arkansas State University (ASU) in Jonesboro (Craighead County), the first African-American director of the Federal Highway Administration, and U.S. secretary of transportation.

Rodney Slater was born on February 23, 1955, in Tallahatchie County, Mississippi. Soon after, Slater’s mother married Earl Brewer, a mechanic and maintenance man about whom Slater has said, “My stepfather was my father.” When Slater was a small child, the family moved across the Mississippi River to Marianna (Lee County), where, by age six, Slater was picking cotton in the fields with his mother. Slater picked cotton and peaches throughout his youth to supplement the family’s income despite his father working five or six jobs to provide for Slater, his two younger brothers, and two younger sisters.

Slater attended segregated schools in Marianna until the eleventh grade, when he attended the newly integrated Lee High School, where he was a class officer. In 1972, city officials charged him with inciting a riot during a student demonstration on Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday. He and other students were taken to the police station, booked, and charged. John Walker, a civil rights attorney from Little Rock (Pulaski County), helped to get the charges dropped, but Slater was prohibited from participating in extracurricular activities his senior year. This was significant because Slater was a star halfback on the school football team and had hoped to attend college on an athletic scholarship.

Despite the setback, he was offered academic and athletic scholarships to Eastern Michigan University in Ypsilanti, where he was a running back and was voted team co-captain. He was on the dean’s list each semester and graduated in 1977 with degrees in political science and speech communications.

Returning to Arkansas, Slater entered law school at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County). He was president of the UA chapter of the Black American Law Students Association and the Student Bar. While he was in law school, his future father-in-law, Arkansas state representative Henry Wilkins III, introduced him to Bill Clinton, then governor of the state. Slater also met George Haley, brother of Roots author Alex Haley and the second African American to graduate from the UA School of Law; Haley became a longtime mentor to Slater. Graduating with a juris doctorate in May 1980, Slater was admitted to the state bar in August.

From 1980 to 1982, he served as an assistant attorney general in the litigation division under Attorney General Steve Clark. In 1982, he left that office to join Clinton’s staff, also serving as his deputy campaign manager in 1984 and 1986. Clinton appointed Slater special assistant to the governor for community and minority affairs, followed by the position of executive assistant to the governor for economic and community programs. In 1987, Clinton named him to the Arkansas Highway Commission, where he was the youngest commissioner and the first African American to serve on that state board. Slater was elected chairman in December 1992.

From 1987 to 1992, Slater was also director of governmental relations for ASU in Jonesboro. Taking a leave of absence from ASU, Slater served as deputy campaign manager and senior travel adviser for the 1992 Clinton–Gore presidential campaign. After Clinton’s election, Slater served as an aide to Clinton’s transition director, Warren Christopher. Clinton named Slater director of the Federal Highway Administration in March 1993. The agency’s first African-American administrator in its century-long history, Slater developed an innovative financing program that resulted in the completion of hundreds of projects ahead of schedule with greater cost efficiencies. His agency provided major assistance in transportation infrastructure to California after the Northridge earthquake in 1994.

His wife, attorney Cassandra Wilkins-Slater, originally from Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), was appointed senior adviser to the Social Security commissioner in 1994. Their daughter, Bridgette Josette, had been born earlier that year.

Slater was popular with both political parties. President Clinton said, “I had Republican congressmen calling me, saying, ‘You ought to name Slater to be secretary of transportation.’” On February 14, 1997, Slater replaced Federico Pena as transportation secretary, overseeing the nation’s highways, airways, railways, and waterways. He held the post until the end of the Clinton administration in 2001.

As transportation secretary, Slater proved popular with the legislative and executive branches of government as well as industry officials. Only activist Ralph Nader was critical, saying Slater’s plans to improve national highways would allow people to go faster and thus increase fatalities. Slater secured bipartisan support in Congress for projects such as the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21), a record $200 billion investment in surface transportation; the Wendell H. Ford Aviation Investment Reform Act for the 21st Century (AIR-21), which provided a record $46 billion to provide for the safety and security of the nation’s aviation system; and the negotiation of forty Open Skies Agreements with other countries, expanding U.S. reach in aviation and promoting U.S. carrier access to international markets. Under his leadership, the first International Transportation Symposium was held, with representatives of more than ninety countries in attendance.

Slater lives with his wife and daughter in Washington DC. He is a partner in the law firm Patton Boggs LLP, where he heads the transportation and infrastructure practice group. Along with fellow Arkansan Wesley Clark, Slater is a partner with James Lee Witt Associates, a Washington consulting firm specializing in emergency management. Slater is a public speaker on topics including global transportation, critical infrastructure, international transportation negotiations, and labor-management issues for aviation, rail, highways, and maritime and transit systems.

His honors and recognitions include the 1994 Black Alumni Achievement Award from Eastern Michigan University (EMU) and an honorary doctorate from EMU in 1996. In 1998, Ebony magazine named him one of the 100 Most Influential Black Americans and the Arkansas Times named him an Arkansas Hero. That year, the National Bar Association gave him the President’s Award. In 1999, he received an honorary doctorate from Howard University in Washington DC and the Lamplighter Award for Public Service from the Black Leadership Forum. In April 2006, Slater was honored by the University of Arkansas as a recipient of the Silas Hunt Legacy Award, and at commencement the following month, Slater received an honorary doctorate of laws from UA. He has also served on the board of Philander Smith College in Little Rock, as well as the boards of Northwest Airlines, the Smithsonian Institution, Kansas Southern Industries, the Urban League, the United Way, the National Museum of American History, and Verizon and is a part owner of the Washington Nationals baseball team (formerly the Montreal Expos) as well as a partner in the Washington DC law firm Squire Patton Briggs.

At the time of Slater’s confirmation by the U.S. Senate as transportation secretary, Ernest Green, one of the Little Rock Nine, said Slater’s story offered a lesson for all young people regardless of race or class: “You, too, can make it and have an impact on this country.”

For additional information:

“Arkansas Memories: Interviews from the Pryor Center for Arkansas Oral and Visual History—Rodney E. Slater.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 70 (Spring 2011): 69–77.

Clinton, Bill. My Life. New York: Knopf, 2004.

Fullerton, Jane. “Slater Family Leads Cheers at Confirmation Hearing.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 30, 1997.

Lockwood, Frank E. “Baseball Team Owner Says Eye on Bigger Game.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 8, 2017, pp. 1A, 11A.

Lunsford, Scott. Interview with Rodney Slater, March 15, 2006. David and Barbara Pryor Center for Arkansas Oral and Visual History, University of Arkansas. http://pryorcenter.uark.edu/interview.php?thisProject=Arkansas%20Memories&thisProfileURL=SLATER-Rodney&displayName=Rodney%20Slater&thisInterviewee=429 (accessed August 26, 2023).

Randolph, Laura B. “Power Couples—High Profile Couples.” Ebony, January 1999, 34.

Sadler, Aaron. “Slater Stays Loyal to Arkansas while Making Splash in D.C.” Jonesboro Sun, August 13, 2006, pp. 1–2.

“Slater Will Take a Few Months to Consider Future.” Jonesboro Sun, January 22, 2001.

“Traveling in the Fast Lane: Transportation Secretary Rodney Slater.” Ebony, March 1998, 110.

Whitsett, Jack. “Slater Lands at Beltway Firm.” Arkansas Business. May 14, 2001, p. 10.

Nancy Hendricks

Arkansas State University

Mississippi Cruise

Mississippi Cruise  Rodney Slater

Rodney Slater  Rodney Slater

Rodney Slater

I would like to add to your narrative concerning Rodney Slater. My father, Judge Cecil C. Matthews, was the judge chosen from among his peers to preside over the Marianna Race Trials in 1972. I was a journalism student at the University of Arkansas at the time, when journalism department chair Jess Covington was teaching a course on current events. We were all discussing this case when I mentioned that my father, Stuttgart Municipal Judge Cecil Matthews, was traveling back and forth every day with a state police escort to preside over these trials. I cannot remember how long they lasted, but my family back home in Arkansas was receiving multiple death threats pertaining to this ordeal for which he never received any payment whatsoever. How strange to witness Rodney Slaters political star ascending in the years afterward. Life is stranger than fiction.