calsfoundation@cals.org

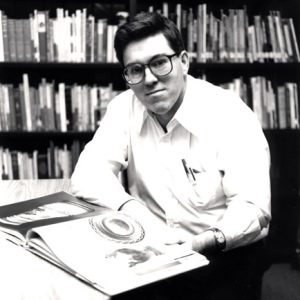

W. K. McNeil (1940–2005)

aka: William Kinneth McNeil

William Kinneth (W. K.) McNeil was a prominent folklorist and historian of Arkansas and Ozark regional folk traditions, especially their folk music and songs, speech, tales, and legends. He published books and articles in both popular and scholarly outlets and produced widely disseminated recordings. Most of his research was conducted while he held the post of folklorist from 1976 to 2005 at the Ozark Folk Center in Mountain View (Stone County), from which he drew materials for his public programming as well as writing.

W. K. (or Bill) McNeil was born near the town of Canton, North Carolina, on August 13, 1940, to William McKinley McNeil, a sales manager, and Margaret Winifred (Rigdon) McNeil, an office worker; he had one sister. He received a BA in history at Carson-Newman College in Jefferson City, Tennessee, in 1962, before moving on to Oklahoma State University (OSU) to continue his historical studies and earn a master’s degree in history in 1963. He moved on to doctoral work in history at OSU, but he was frustrated by the lack of attention to fieldwork and cultural material in historical studies. In 1966, after serving with the Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA) in Kentucky, he enrolled in the State University of New York’s newly formed Cooperstown Graduate Program in American folk culture, combining historical and ethnological perspectives on American culture. He earned his master’s degree in 1967 and stayed in New York to work as a public historian for the New York Office of State History in Albany, before taking up doctoral study in folklore at Indiana University in 1970; he received a PhD from the university in 1980.

In 1975, he became administrator for the Regional America Program of the Smithsonian Institution’s Festival of American Folklife, and, in 1976, he settled into the job he held the rest of his life as folklorist at the Ozark Folk Center. At the center, he organized folklore education programs, established one of the country’s largest regional folklore libraries and archives, and engaged in fieldwork in the region. He built on the legacy of renowned Ozark folklore collector Vance Randolph and expanded the range of traditional materials documented, as well as giving them more analysis. He received major grant funding for oral history projects in Arkansas (1980), compiling a history of Arkansas country music (1982), and a survey of Arkansas folk singers and storytellers (1996). Beginning in 1977, he regularly contributed columns on Ozark folksongs to the magazine Ozarks Mountaineer, as well as “Arkansas Dance Tunes” for The Arkansas Country Dancer, and “An Ozark States Discography” in issues of Mid-America Folklore. Beyond these regional publications, he held the national post of book review editor of the Journal of American Folklore from 1980 to 1993 and joined the executive board of the National Council for the Traditional Arts in 1979. In 1980, he was elected president of the Mid-America Folklore Society, and later in the 1980s, he became editor of the music magazines Old Time Country and Rejoice: The Gospel Music Magazine. He was frequently called upon as a consultant for folklore projects, including guiding the choice of ballads sung in the popular movie Songcatcher (2000), about folk song collecting in early-twentieth-century Appalachia.

He began issuing collections of regional folklore as books during the 1980s while editing the American Folklore series for August House publishers in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and a reprint series of classic books in folklore studies for the Clearfield Company. He received popular recognition for his work with the publication of Ghost Stories from the American South (1985) by August House, which became a mass market paperback. The subjects of his other books focused on the folk regions of the Ozarks and Appalachian Mountains, as well as folk songs and humor in the South, including Ozark Country (1995), Southern Folk Ballads (1987, 2 volumes), Southern Mountain Folksongs (1993), Appalachian Images in Folk and Popular Culture (1989), and Ozark Mountain Humor (1989). A large editorial project that had occupied him for many years was issued after his death as the Encyclopedia of American Gospel Music (2005).

McNeil was also active in producing recordings and writing liner notes. He received acclaim for his box sets such as The Blues: A Smithsonian Collection of Classic Blues Singers (1993) for the Smithsonian Institution and Somewhere in Arkansas: Early Country Music: Recordings from Arkansas, 1928–1932 (1997) for the Center for Arkansas and Regional Studies at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County). He also put folk narratives on recordings such as Not Far from Here: Traditional Narratives and Songs Collected in the Arkansas Ozarks (1981) and produced a recording of the religious songs of renowned ballad singer Almeda Riddle, How Firm a Foundation (1985).

In 1994, he married Grace Joy Taucan Morandarte, an immigrant from the Philippines, in Arkansas; they did not have any children and later divorced.

McNeil’s analytical concern was to show, contrary to popular perceptions, that Ozark folk culture is complex and constantly evolving and adapting. Another point that he emphasized in his writing is that while the Ozarks has for much of its history been geographically remote, it has not been culturally isolated. With his vast comparative knowledge of folk traditions, he showed how Ozarkers had been influenced by the culture of other areas, particularly by that of southern Appalachia. Yet he also underscored, particularly in Ozark Country, the distinction of many Ozark traditions from Appalachia in style and content and resisted the regional characterization of Arkansas and the Ozarks as “Appalachia West.” Looking into origins and development of traditions, people, and regions throughout history was essential to him. He worried that, without the foundation of history, folklorists would be “careless explorers, they know where they are but not how they got there.”

McNeil died of a heart attack on April 19, 2005, in Mountain View.

For additional information:

Baker, Ronald L. “In Memoriam: W. K. McNeil (1940–2005).” Journal of Folklore Research 42.2 (2005): 361–63.

Bronner, Simon J. “Remembering Bill McNeil (1940–2005).” Folklore Historian 22 (2005): 5–12.

———. “W. K. McNeil (1940–2005).” Journal of American Folklore 119 (Summer 2006): 356–361.

Woodworth, Hillary. “William Kinneth McNeil: Folklore Historian.” Arkansas Democrat Gazette, April 22, 2005, p. 8B.

Simon J. Bronner

Pennsylvania State University

W. K. McNeil

W. K. McNeil  W. K. McNeil

W. K. McNeil

I corresponded with Bill for probably ten years, and we exchanged records, tapes, books, and CDs. His magazine Old Time Country did a lot for Australian country music, as he published articles on Australian country music and encouraged me to write articles. I was always grateful for his encouragement, and for the genuine interest he had in the Australian Bush Ballad. He was very helpful to me in giving his folklorist’s opinion of the bush ballad. Knowing I was a fan of Grandpa Jones, he sent me an autographed picture signed by Grandpa and Ramona when they were living in Mountain View. I was saddened by his death, which came as a surprise to me. He made a big impact on me. He was an expert on old-time country music.

I corresponded with Bill, swapped music with him, and wrote some articles for Old Time Country. He was very encouraging and highly knowledgeable, although I suspect he would have liked more money to buy albums. He said he was working on a book about Elton Britt.

Doctor McNeil was a great friend to all those interested in the folklore of the Ozarks. He helped me many times with lyrics and Ozark ideas. I’ll be forever grateful to him. RIP, my friend. You left us way too soon.