calsfoundation@cals.org

American Civil Liberties Union of Arkansas

aka: ACLU of Arkansas

aka: Arkansas ACLU

The American Civil Liberties Union of Arkansas (ACLU of Arkansas) is an affiliate of the American Civil Liberties Union, which is devoted to protecting the personal liberties guaranteed by the Bill of Rights as well as later amendments to the U.S. Constitution.

The national organization, which like the Arkansas affiliate is nonprofit and nonpartisan, was formed in 1920. The Arkansas affiliate was organized in 1969 and subsequently established its headquarters in Little Rock (Pulaski County). Both organizations lobby the legislative branches of government on civil liberties issues and supply legal counsel to people who believe their freedoms have been violated by some level of government or by individuals or businesses acting under the protection of government. The state organization also engages in educational activities on the importance and meaning of the Bill of Rights.

Civil cases prosecuted by the ACLU or in which the ACLU intervened and supplied briefs have formed important judicial law at the state and federal levels. For instance, the national ACLU intervened in an Arkansas lawsuit brought by Susan Epperson, a biology teacher at Central High School in Little Rock, challenging a 1928 Arkansas law barring schools from teaching “that mankind ascended or descended from a lower order of animals.” The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Epperson v. Arkansas in 1968 that the Arkansas law violated the First Amendment, which forbids the establishment of official religion.

In 1968, the national office of the ACLU in New York furnished the names of Arkansas contributors to the ACLU and offered to send a staff member to Arkansas to help form a state affiliate. At that time, there were a handful of states that did not have a formal affiliate. A planning meeting was held at the Little Rock home of Fred K. Darragh, a businessman and philanthropist. The meeting was attended by several labor lawyers and a Little Rock advertising executive, Ted Lamb, who was a member of the Little Rock School Board. Herbert Bingaman of the United Auto Workers (UAW) arranged a wider organizational meeting of about thirty people who were members of the national ACLU at the UAW hall (attended by a representative from the national ACLU headquarters). After the national ACLU staff member explained how ACLU membership dues would be shared between the national organization and the state affiliate, a motion to incorporate ACLU of Arkansas was passed. The affiliate was incorporated on January 12, 1969. The first officers were elected: Morton Gitelman, a law professor at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville (UA), was elected chair; Betty Siegel, vice-chair; and Otto “Bud” Zinke (a physics professor at UA), secretary. Gitelman also agreed to serve as chair of a legal panel. In 1970, Gitelman resigned as chair because of his acceptance of a visiting professorship at the University of Illinois. Zinke agreed to take over the chairmanship, although Gitelman continued to chair the legal panel, long distance. The group did not have an office or a staff at first. In 1975, the board of directors hired Nan Selz of Little Rock as the first paid executive director.

In February 1969, the affiliate’s first case followed the arrest and jailing at Arkadelphia (Clark County) of Joe Neal and his wife of Fayetteville (Washington County), who were “state travelers” for the Southern Student Organizing Committee. They were talking to students about civil rights and the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) at the student union of Henderson State College (later Henderson State University) when the dean of students and police arrived. The couple refused an order to leave the campus and the city. Jim Guy Tucker, a young Little Rock lawyer who was one of the Arkansas ACLU founders and who later served as governor, posted their bond and defended them for the ACLU. They were charged with disobeying an officer and violating an Arkansas statute prohibiting “offensive talk” on school property. Municipal Judge J. E. Still fined them $500 each and sentenced them to six months in prison, which was suspended on the condition that they agree not to return to Arkadelphia. The Arkansas Supreme Court, in the case of Neal v. Still, reversed their convictions and invalidated the speech statute under which they were charged.

In 1973, the ACLU of Arkansas came to the defense of Grant Cooper III, an assistant professor of history at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR) who was not rehired after a tempest caused by disclosures that he was a member of the leftist Progressive Labor Party and that he taught history from a Marxist perspective. The controversy spawned multiple lawsuits, one (Cooper v. Henslee, et al.) by a group of state legislators demanding that he be fired under a state law barring employment of people with subversive allegiances. The Arkansas Supreme Court invalidated the law, and in another suit against the university, a federal judge ruled that Cooper had been fired not because of poor classroom performance but because of his political conduct. The court concluded that “at least in the context of a university classroom, Cooper had a constitutionally protected right simply to inform his students of his personal political and philosophical views.” The opinion observed that the teacher had “encouraged students to challenge and dispute his views.” Gitelman, who was chair of the ACLU Legal Panel, Philip E. Kaplan and John Bilheimer of Little Rock represented Cooper for the ACLU.

The ACLU of Arkansas’s biggest case came in 1981 after the state legislature enacted legislation requiring that whenever evolution was taught, schools had to give “balanced treatment” to the Bible’s account of the creation of the universe. Governor Frank White signed the bill into law. The trial in December 1981 attracted international attention similar to the famous “Scopes Monkey Trial” (State of Tennessee v. John T. Scopes). Kaplan was the lead attorney for the ACLU and for several Arkansas clerics who were plaintiffs in the case, McLean v. Arkansas Board of Education. U.S. District Judge William R. Overton of the Eastern District of Arkansas invalidated the law, Act 590 of 1981, because the requirement that schools teach the divine creation of the universe amounted to the establishment of a religion, which was forbidden by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The state did not appeal Overton’s ruling.

Much of the work of the ACLU of Arkansas has dealt with infringements of the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of speech, press, religion, and assembly. Its lobbying and litigation frequently were aimed at protecting the right of women to obtain abortions and at discriminatory restrictions on gay and lesbian people. In 2006, in a lawsuit brought by the ACLU, the Arkansas Supreme Court invalidated a state regulation that prohibited gay and lesbian couples from serving as foster parents for neglected and abused children.

Numerous ACLU cases in the 1990s and the first decade of the new century dealt with the free-speech, religious, and privacy rights of students in the public schools. Most of the cases were resolved before trial. One of its most significant legal triumphs was a 1994 order by the Arkansas Supreme Court invalidating a statute barring deaf and hearing-impaired people from serving on juries.

The ACLU of Arkansas hired Rita Sklar as the executive director in 1993, and as the organization’s spokesperson, she became a prominent voice in public affairs. The affiliate hired its first full-time staff attorney in 2003, but it continued to rely on what it called “cooperating attorneys” around the state to handle most of its litigation. In 2006, it had about 3,500 members. Sklar announced her retirement in 2019, and Holly Dickson took over as executive director the following year.

For additional information:

ACLU of Arkansas. http://www.acluarkansas.org/ (accessed August 26, 2023).

Herzog, Rachel. “ACLU’s State Director Retires.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, July 16, 2019, pp. 1B, 6B.

Kellams, Laura. “Standing on Her Principles.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 2, 2005, p. 1.

Ernest Dumas

Little Rock, Arkansas

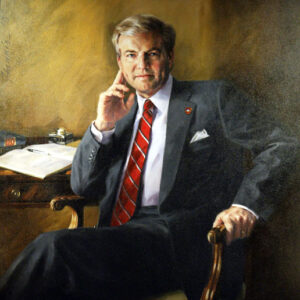

Fred Darragh

Fred Darragh  Susan Epperson

Susan Epperson  Jim Guy Tucker

Jim Guy Tucker

The first organization meeting of the ACLU was held in 1969 in the AFL/CIO union hall in Little Rock. Among those present were Ted Lamb, John Sizemore, Fred Darragh, Herb Bingamin, Bill Becker, Mort Gitelman, Betty Siegel (I think), and myself. At that time there were about 70 members of the national ACLU scattered around Arkansas with a small concentration in Little Rock and a larger one in Fayetteville. Mort Gitelman was elected the first chair, Betty Siegel the vice chair, and I the first secretary. I took over as the second chair after Mort served a year. Mort served as head of the legal panel for the first six or seven years. He had the uncanny ability of getting good lawyers (members and non-members) to represent us. We didn’t have a state telephone, so I had one with a Little Rock number installed in my home in Fayetteville. I came to believe that the number was scrawled on the walls of every drunk tank of every small town in Arkansas for use only between 11:00 p.m. and 5:00 a.m. The callers could only rarely remember whether their rights had been read them or not. Seriously, the affiliate was formed because the national ACLU had its hands full with national issues and the results were not filtering down to the courts in Arkansas very efficiently. People brought before the courts on these issues were not being represented properly. We were entering a period where civil rights and women’s rights issues needed more local representation.