calsfoundation@cals.org

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment

Arkansas’s cultural record may begin on the state’s eastern edge, with a painted buffalo skin made by the Quapaw, nine figures in a line, the one at the left with a rattle. Or perhaps it begins still earlier, with fragments of cane flutes and whistles from ancient Indian tribes from the Ozarks. These offer only the briefest of hints, a mere glimpse of Arkansas’s earliest peoples, but enough to make it clear that they entertained themselves and that there were dancers, musicians, and artists among them. A millennium later, Arkansans were entertaining themselves at the King Biscuit Blues Festival in Helena-West Helena (Phillips County), or maybe the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival in Hot Springs (Garland County). They celebrated the successes of home-grown authors, architects, painters, film stars, athletes, and pop music icons. From before the frontier to after the new millennium, the story of the arts in Arkansas is a rich and varied tale.

Beginnings

The written record, once Europeans arrive, thickens a bit. René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, arriving at the Quapaw village of Kappa in the spring of 1682, was welcomed with the music of “gourds full of pebbles and two drums, which are earthen pots covered with dressed skin.” A very similar welcome greeted Henri Joutel five years later, in 1687, and an Osage musician encountered a century and a half later by Victor Tixier had somehow acquired “the body of a clarinet,” constructed his own reed and mouthpiece, and repeatedly serenaded his visitor with the single three-note song that made up his entire repertoire. Early settlers in the Ozarks told pioneer historian Silas Turnbo of “green corn dances” involving whole communities, including white visitors, though when the latter danced, “the Indians would make sport of their awkwardness.”

Further south, reports from Arkansas Post and the pioneer settlements along the Arkansas River reveal a similar devotion to entertainments. The Frenchman François Marie Perrin du Lac, writing at the beginning of the nineteenth century, noted that the inhabitants of Arkansas Post spent their leisure time “playing games, dancing, drinking, or doing nothing.” James Miller, the first territorial governor, described the Post’s musical culture in unflattering terms reminiscent of Tixier’s Osage clarinetist: “[T]hey have one fiddler who can play but one tune.” In 1819, English botanist Thomas Nuttall was no less dismayed with the upriver frontier, reporting that “love of amusements, particularly gambling and dancing parties or balls,” was “carried to extravagance.”

A higher culture, however, was on the way. By 1834, the geologist George W. Featherstonhaugh, traveling in the territory’s southwestern region, was astonished to find “a piano in the wilderness” at a home in Hempstead County. Just less than a decade later, the German traveler Friedrich Gerstäcker encountered sacred and secular music in isolated Ozark and Ouachita settlements. He was put off by the music at a Methodist meeting (the minister “thundered out a hymn with a voice that astounded me”) but was much impressed by the endurance of revelers at a July 4 frolic near the Fourche le Fave River. The first fiddler went down early in the evening after profanely expressing “a most disagreeable wish respecting the eyes of all the company, on account of the dryness of his throat, which had only had the contents of two bottles of whisky down it.” His replacement lasted until midnight, but then he also faltered and, like his predecessor, “was carried out and laid on the grass while a third was soon found to take his place.”

By the time Gerstäcker was hunting in what is today Madison County, settlement had been under way for fifty years or more, and a pattern had been set. Arkansas would be a rural state; for most of its history, an overwhelming majority of the population would be engaged directly or indirectly in agricultural occupations. Towns like Little Rock (Pulaski County) and Batesville (Independence County) developed along navigable rivers, as commerce in the days before railroads depended heavily upon steamboat transport. The settlers arrived from many places and from varied ethnic, class, and religious backgrounds, but most came from other Southern states. Few brought with them aristocratic backgrounds or enormous wealth, and when they claimed a church affiliation, it was most often Baptist or Methodist.

Early Authors and the State’s Enduring Image

The name of Arkansas had, by this time, been carried to the nation’s notice through the accounts of travelers like Nuttall, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Featherstonhaugh, and Gerstäcker, and by the sketches of the state’s first fiction writers. Whether drawn by the ostensible fact of the traveler’s report or by the admitted fiction of the humorous tale or local color story, the picture was equally unlovely and strikingly similar. Even before statehood (Arkansas Territory was established in 1819; statehood came in 1836), the very name of Arkansas was notorious. According to James Masterson’s pioneering 1942 Tall Tales of Arkansaw, the state was, “more than any other State in the Union… a target for reproach and ridicule.” Two qualities, especially, were at the center of this “ill fame.” The settlers and new citizens were, in the first place, unlettered and uncouth and, in the second place, astonishingly fond of violence. Henry Rowe Schoolcraft stresses both characteristics in describing his Christmas holiday visit with pioneer settlers on the White River in 1818 and 1819. “Schools are unknown,” he wrote, “and no species of learning cultivated.” Schoolcraft was especially appalled by two stabbings resulting from the “childish disputes” of boys during his stay: “No correction was administered in either case, the act being rather looked upon as a promising trait of character.”

Very similar traits are highlighted in the famous “Pete Whetstone” letters of Charles F. M. Noland, a Batesville attorney who has as good a claim as any to being Arkansas’s first literary figure. Along with Thomas Bangs Thorpe (a New Yorker transplanted to Louisiana whose “The Big Bear of Arkansas” is still widely anthologized), he was the most prolific contributor of Arkansas sketches to The Spirit of the Times, the New York sporting periodical that was the primary publication outlet for Southwestern humor. In “Pete Whetstone’s Last Frolic,” the narrator needs help in identifying a piano (“pe-anny”), while “Dan Looney’s Big Fight in Illinois” features a protagonist who finishes off a fallen opponent by jabbing his thumbs into his eyes: “I played my thumbs into his eyes, and he sung out; but before they got me off, I reckon my right thumb got mighty near to the fust jint.” The use of the piano as a badge of cultured sensibility, in such stories as the former, is recurrent, as in Featherstonhaugh’s surprise at its presence in Hempstead County. Thorpe’s “A Piano in ‘Arkansaw’” chronicles the sudden loss of prestige visited upon a small community’s cultural standard bearer when he confidently identifies as a piano what is, in fact, a washing machine. There is also a strong gendering of musical instruments—fiddles are played by men at public dances, but pianos are played by women in private homes. Instruction in piano was not infrequently a curricular offering of the “female academies” that were a feature of early education in the state. Humorists like Noland and Thorpe set in motion a comic tradition that was dominant in early Arkansas writing—Marcus Lafayette Byrn’s The Life and Adventures of an Arkansaw Doctor by David Rattlehead, M. D. (1851) was another pioneering entry—and remains strong even in contemporary Arkansas writers. Charles Portis’s several novels, especially The Dog of the South (1979), are outstanding modern examples of this tradition.

Before the century was out, the infamy of Arkansas as a sink of ignorance, violence, and squalor had been immortalized in the nation’s most enduring literature. For violence, there is the passage in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick comparing Captain Ahab to an “Arkansas duellist” for his insane assault with a six-inch knife upon the “fathom-deep” heart of the whale; for ignorance and gullibility there is the scene in Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, in which the Duke and the King, posting a billboard advertising the Royal Nonesuch, lure “Arkansaw lunkheads” by adding the line, “Ladies and Children Not Admitted.” “There,” says the Duke, surveying his design, “if that line don’t fetch them, I don’t know Arkansaw.”

Alice French is mostly forgotten now, but in 1900, she was much better known than Melville, and her widely read sketches and stories set in northeastern Arkansas contributed to the sorry image of Arkansas. Her 1891 “Plantation Life in Arkansas,” published in the Atlantic Monthly, was especially grim, with a plantation manager’s bloody travelogue during a nine-mile wagon ride to town so appalling his visiting New England sister that she finally orders a stop: “He stopped so often to relate how ‘a man was killed just here’ that his sister finally exclaimed: ‘If Frank stops everywhere somebody was killed we sha’nt get to Portia until dark! I never was in such a gory country.’” The violence of the Arkansas frontier is also stressed in Alfred Arrington’s luridly titled collection of 1847, Desperadoes of the South-West: Containing an Account of the Cane-Hill Murders, Together With the Lives of Several of the Most Notorious Regulators and Moderators of that Region. As late as the 1870s, an Osceola (Mississippi County) newspaper reported on picnic amusements that would seem shockingly barbaric to many today: “After eats, gander pulling was engaged in. W. P. Hale succeeded in pulling in twain the gander’s breathing apparatus, after which dancing was resumed.”

The “Arkansas Traveler”

Things get a bit more complex, however, with “The Arkansas Traveler,” the combination fiddle tune, comic dialogue, and painting (two paintings, actually) that quickly became the most widely known piece of Arkansiana. Its origins are shrouded in mystery, but by 1845, it was known as a fiddle tune, and by 1849, it had been reported as the name of a race horse and as the most popular dance tune in Hot Springs. The dialogue (most often credited to Arkansas planter Sanford C. Faulkner) was in print before 1860, and in 1869, a stage play titled Kit, the Arkansas Traveler opened in Buffalo, New York, and held the stage through the end of the century. Arkansas artist Edward Payson Washbourne undertook two paintings of the scene in the 1850s (he completed The Arkansas Traveler but apparently left The Turn of the Tune unfinished). Both were widely distributed as lithographs. By 1902, the tune was on record, and a 1922 version featuring fiddlers Henry Gilliland and Arkansas-born “Eck” Robertson performing “Sally Goodin’” and “The Arkansas Traveler” is often cited as the first country music record.

The story at the heart of all these productions is a simple tale offering at least a partial rejoinder to the calumnies of the emerging image of Arkansas. A solitary horseman of elevated station approaches an isolated mountain cabin, in the doorway of which a homesteader plays the first part of a jig called “The Arkansas Traveler” over and over. The encounter gets off to a poor start. The settler responds rudely to several inquiries (this constitutes the humorous dialogue) and offers no welcome, but when the traveler offers to play the jig’s second part (the “turn of the tune”), he is suddenly accorded the warmest of hospitality. The “notorious” stereotypes are certainly available here—the homesteader’s cabin is an ill-maintained shack, his home clearly doubles as a saloon, and he cannot even form the letters on his “whisky” sign correctly—but the mountaineer is not entirely a figure of fun. He holds his own in the verbal duel with the traveler, and in the friendly ending, he reveals himself as capable of a generous hospitality.

Education and Frontier Social Life

Such accounts, along with other, less sensational portraits of Arkansas life (an especially good example would be the stories of Ruth McEnery Stuart, popular in the 1890s, whose “Simpkinsville” is modeled on Hempstead County’s Washington community), make clear that Arkansas in its frontier period was a place where settlers entertained themselves, often by turning routine activities into social events, and procured a wide range of household articles and luxury items from local artisans. Female quilters did most of their work in family, church, and community groups. Like their piano-playing sisters, they practiced their art in a domestic setting and were rarely paid. Potters, basketmakers, gunsmiths, cabinetmakers, silversmiths, painters, and daguerreotypists (all overwhelmingly male) were often either itinerant workers, marketing their wares over a larger region. Henry Byrd, the state’s best-known nineteenth-century painter, is known to have worked in Little Rock, Fort Smith (Sebastian County), Camden (Ouachita County), El Dorado (Union County), and Batesville.

John Quincy Wolf, born on the upper White River in 1864, was old enough to remember log rollings and house raisings as “big social occasions… that drew people from miles around.” Harvest gatherings (“reapings”) and summer religious revivals (“brush arbor meetings”) also served as social occasions and were appreciated by young people as courting opportunities. Public executions (and lynchings) were too infrequent to be routine, but they often drew enormous crowds. An 1839 hanging in northwest Arkansas reportedly attracted nearly 1,000, a group described in an early Benton County history as “a surging mass of humanity, white, black and red, all impatient for the exciting event, and fearful lest it be postponed.” Shooting matches were also popular and drew large crowds. When Albert Pike broached the idea of establishing a school to a Van Buren (Crawford County) settler in 1833, he was advised to “write it out as fine as you can” and make a direct pitch: “[I]n the morning there’s to be a shooting match here for beef, nearly all the settlement. . . will be here, and you’ll get signers enough.” Wolf also makes clear, despite Gerstäcker’s unflattering portrayal, that fiddlers were much respected in the pioneer settlements: “The country fiddler was an important personage, looked upon with almost as much reverence as the country parson.”

Not all entertainments were rooted in practical matters. The abysmal educational conditions deplored by Schoolcraft were gradually ameliorated, first by a wide range of private academies and, later, by the establishment of public schools. From their inception, the rural and small town schools especially were centers of social and educational life, offering a wide range of debates, dramatic presentations, spelling bees, orations, recitations, and various holiday programs for the edification and entertainment of scattered communities. A festive program at the end of the school term developed as a traditional occasion for the young scholars to exhibit newly acquired skills to proud parents and townspeople. Women’s clubs also played an important role in the developing social and cultural life of many Arkansas communities—by 1897, a statewide Arkansas Federation of Women’s Clubs had been organized. Many, like the Osceola Pansy Book Club, were devoted to reading, but others concerned themselves with a wide range of educational and service activities, in addition to providing an important element of community social life.

Arkansans on Radio and Record

Comic sketches of rustic life continued to dominate in the literature devoted to Arkansas, at least in the early decades of the twentieth century. Perhaps the most famous single volume from the period is Thomas W. Jackson’s 1903 big seller, On a Slow Train Through Arkansas, but surely the best known of the state’s turn of the century humorists was Opie Read, whose Little Rock newspaper, The Arkansaw Traveler, launched his prolific career as a lecturer, short story writer, and novelist. Read also held vitriolic opinions about African Americans, and he had plenty of company among the state’s pioneer authors. Though Alice French was more of an equal opportunity bigot, reserving her strongest dislikes for immigrants generally, even the most sympathetic portraits of Native Americans and African Americans in this period are crudely stereotypical and patronizing. Ruth McEnery Stuart’s stories provide good examples, though “An Arkansas Prophet” pushes the envelope a bit by featuring a Black man who not only rescues the village belle but also shoots the Yankee cad who seduces her. The tradition of the comic sketch was carried to the new medium of radio in 1931, when Chester Lauck and Norris Goff, two childhood friends from Mena (Polk County), made their first Lum and Abner radio broadcast on NBC. Their show was hugely and enduringly popular—the rustic philosophers held forth from their “Jot ‘Em Down Store” for nearly twenty five years and also made several Hollywood films in the 1940s. Just slightly later on the scene was Bob Burns of Greenwood (Sebastian County), who got his start as a radio comic in 1935 and was best known for his Arkansas Traveler show in the 1940s.

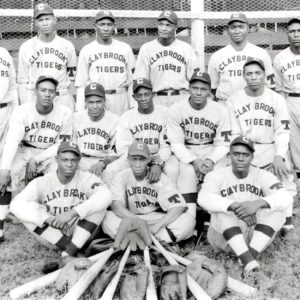

Log rollings, barn raisings, and shooting matches for beef were things of the past by this time, but schools continued to serve as focal points of community entertainment, spelling bees and debates gradually giving way to school plays, band and orchestra concerts, and especially athletic contests. Community baseball teams were avidly supported (see Arkansas novelist Myra McLarey’s Water from the Well for a fine portrayal of a south Arkansas team from the early twentieth century), and over the years, a number of minor-league and semi-professional teams have represented several Arkansas towns. But any reasonable account of Arkansas entertainments would surely accord the top spot on the state’s hit parade to the football teams (and more recently the basketball squads as well) of the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County). Since the 1920s, at least, Razorback football and basketball teams have enjoyed the enthusiastic, not to say fanatical, support of a statewide network of fans.

The rise of radio and phonograph recordings made it possible for Arkansas musicians to dream of fully professional careers. Osceola’s Essie Whitman, a turn-of-the-century vaudeville star who was making records by 1921, may be the state’s first fully professional singer/dancer, but the 1920s and 1930s saw an impressive cast of Arkansas musicians establishing national reputations. They ranged across all genres—the blues of Bill Broonzy, the country and western of Patsy Montana, the ragtime and big band jazz of Scott Joplin and Alphonso Trent, the classical music of Florence Price and William Grant Still, the gospel of Rosetta Tharpe, and the opera of Mary Lewis. By the 1940s and 1950s, the list was larger still, with stars like Elton Britt, Johnny Cash, Louis Jordan, and Roberta Martin gaining fame, and Helena radio station KFFA’s “King Biscuit” show opening the door for a wider professional careers for such stars as Robert Lockwood and Sonny Boy Williamson. The rise of rock and roll sent Ronnie Hawkins, Conway Twitty, Glen Campbell, and Black Oak Arkansas to the notice of a puzzled nation, and before the end of the century, the state could boast an impressive list of stars across the whole range of musical genres, from folk revival singer composer Jimmy Driftwood and country piano man Charlie Rich, to opera singer Mignon Dunn and bass/baritone William Warfield, to bluesman Son Seals, gospel group Point of Grace, and teen Goth stars Evanescence.

Arkansans in Literature, Art, Architecture, Photography, and Cinema

A similar professionalization occurred in other areas. The state’s earliest poets—Pike, Little Rock historian Fay Hempstead, and Fayetteville newspaper editor William Quesenbury, who was also a cartoonist and graphic artist—were avocational producers of verse; they were succeeded by men and women who made poetry a primary vocational choice: most famously John Gould Fletcher, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1939, and more recently Frank Stanford, Miller Williams, and C. D. Wright. The same is true of fiction writers, with gentleman scribblers like Noland succeeded by thoroughly professional writers like Opie Read and Little Rock’s Julia B. “Bernie” Babcock, whose several Abraham Lincoln novels (especially The Soul of Ann Rutledge, published in 1919) were widely popular. Other notable successes would include Maya Angelou (best known for a memoir, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, 1970), Dee Brown (best known for a history, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, 1970), Ellen Gilchrist (best known for a short story collection, Victory Over Japan, 1984), Donald Harington (best known for a novel, The Architecture of the Arkansas Ozarks, 1975), and Douglas C. Jones (probably best known for The Court Martial of George Armstrong Custer, 1976).

Not many Arkansas painters and graphic artists have achieved wide renown, though even the earliest ones (Quesenbury excepted) saw themselves as professional artists. Some Arkansas painters found success in Hollywood, New York, and Chicago—Louis Betts, for example, and, somewhat later, DeWitt Jordan. But others, like Carrol Cloar and Louis and Elsie Freund, managed successful careers within the state. Arkansas’s most successful contemporary painter is probably Donald Roller Wilson, whose meticulously executed fantasies have been widely collected—three Frank Zappa albums featured his artwork on their covers..

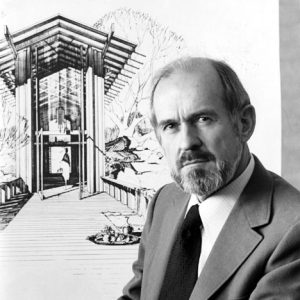

The first architect to advertise his services in Arkansas, according to Ralph Hudson’s 1944 study, “Art in Arkansas,” seems to have been a man named Larrimore, who, in 1844, announced himself as ready to design structures “done in any of the five orders of architecture.” Several of his successors have enjoyed great success—most notably Charles L. Thompson (the Rector Bath House in Hot Springs, Little Rock’s 1907 City Hall), Edward Durrell Stone (the U.S. embassy in New Delhi), and Fay Jones (Thorncrown Chapel in Eureka Springs).

Photographers and daguerreotypists were also active in the early years of statehood, beginning with the arrival in Little Rock of Philadelphia native C. P. Moore in 1842. By 1900, commercial photographers had established themselves in many Arkansas towns—the work of Joseph Shrader, for example, who opened his business in Little Rock in 1910, has been preserved at the Arkansas State Archives, and a selection of the portraits of Heber Springs (Cleburne County) photographer Mike Disfarmer were published to great acclaim in 1976. The work of several African American photographers has been accorded recent attention, with studies and exhibits devoted to the work of Geleve Grice of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), Helena’s Rogerline Johnson, and Little Rock’s Ralph Armstrong.

A number of Arkansans have made reputations on the big screen. Billy Bob Thornton and Mary Steenburgen are among the most recognized, but the first Arkansan to make it big in Hollywood was the versatile Dick Powell. Born in Mountain View (Stone County) in 1904, Powell broke into films in the 1930s as a crooner but moved into hard-boiled roles in the 1940s, most memorably as Phillip Marlowe in the 1944 Murder, My Sweet. The 1950s saw Powell move into television, where he was spectacularly successful both as an actor and a producer, starring in his own Dick Powell Show in the early sixties. Country singer Jimmy Wakely, a native of Mineola (Howard County), also enjoyed a long career as a movie cowboy, as did Elton Britt, best known for World War II’s biggest hit song, “There’s a Star-Spangled Banner Waving Somewhere.”

Today—An Abiding Mix of Old and New

Though Arkansas entered the twenty-first century with increasingly impressive high-culture institutions—fine regional and local art and history museums, a distinguished Arkansas Repertory Theatre (established in 1976), a university press, several symphony orchestras, the enormously successful (but now defunct) Riverfest music festival in Little Rock, the internationally renowned Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival, and the famous Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art—the state retains deep ties to the traditional culture of its original settlers. Thorncrown Chapel matches up nicely with the Jacob Wolf House; Historic Washington State Park, with its lovingly restored antebellum homes and commercial buildings, finds its counterpart in the Ozark Folk Center State Park, with its old-time music programs and traditional arts demonstrations. Arkansas people no longer amuse themselves by strangling geese, but their favorite entertainments are often comic and can still have an edge that rattles the sensibilities of the politically and socially correct.

As recently as the 1980s, the citizens of Yellville (Marion County) were releasing turkeys from low-flying planes as a part of their annual Turkey Trot Festival. Outrage resulting from various “plummeting poultry” stories (in the National Enquirer, among other publications) eventually grounded the birds. The community of Warren (Bradley County), however, still includes tomato eating contests in their town’s annual Tomato Festival; toads are raced in the Toad Suck Daze gala in Conway (Faulkner County); watermelon eating contests are a featured part of the Hope Watermelon Festival; turtles have been racing in Lepanto (Poinsett County) since 1930; caber tossing and bagpipe music enthusiasts (usually about 8,000 of them) assemble in Batesville each year for the Arkansas Scottish Festival, Stuttgart (Arkansas County) now draws more than 60,000 people each year to its World Championship Duck Calling Contest (first held in 1936), and Juneteenth celebrations are held throughout the state.

The same rich mix is found in Arkansas sports. Thanks to federal Title IX legislation, Arkansans cheer their daughters’ high school and college volleyball, gymnastics, and softball games, and soccer has at last started to gain something of the same popularity it enjoys elsewhere. But it remains true that school and college baseball, basketball, and most of all football teams retain their central place in Arkansas community life. From Thursday (junior high) through Friday (high school) and Saturday (college), from the smallest towns to the state’s biggest cities, it is understood that fall evenings are devoted to families gathering at the local stadium to applaud the bands and cheerleaders and root for the victory of local squads.

Underneath all the changes, its gender associations scrambled, the old contrast of the fiddle and piano, popular entertainment and highbrow culture, still holds. It is almost fair to say that Arkansas started with only the former—that, in the beginning, emissaries of the latter arrived only rarely, and for short stays. It has been a long and sometimes difficult climb from the time when schools were “unknown” and state legislators went after each other with Bowie knives to today’s universities and museums and symphonies.

But the drive was always there. It is important to notice (though nobody does), that the settlers mocked in those southwestern humor sketches for their ignorance of pianos were eager to learn. Whole towns gathered at the announcement of the new instrument’s demonstration. And they did learn—Arkansas people imported and made their own, at great cost and enormous effort, the piano and all it stood for, even as they held on tenaciously to the fiddle and all it signified. Today, they still cherish both as their own uniquely mixed heritage.

For additional information:

Bennett, Swannee, and William B. Worthen. Arkansas Made: A Survey of the Decorative, Mechanical, and Fine Arts Produced in Arkansas, 1819–1870. 2 vols. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990–1991.

Brown, Sarah. “The Arkansas Traveler: Southwest Humor on Canvas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 46 (Autumn 1987): 348–375.

Cochran, Robert. “‘All the Songs in the World’: The Story of Emma Dusenbury.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 44 (Spring 1985): 3–15.

———. “‘Low, Degrading Scoundrels’: George W. Featherstonhaugh’s Contribution to the Bad Name of Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 48 (Spring 1989): 3–16.

———. Our Own Sweet Sounds: A Celebration of Popular Music in Arkansas. 2d ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2005.

———. A Photographer of Note: Arkansas Artist Geleve Grice. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

———. “Ride It Like You’re Flyin’: The Story of ‘The Rock Island Line.’” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 56 (Summer 1997): 201–229.

Curtis, Dorris. Come Walk With Me: The Art of Dorris Curtis. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2004.

Dougan, Michael B. “Bumpkins and Bigots: The Arkansas Image in Fiction.” Publications of the Arkansas Philological Association 1 (1975): 5–14.

Guilds, John, ed. Arkansas, Arkansas: Writers and Writings from the Delta to the Ozarks, 1541–1969. 2 vols. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

Horse Capture, George, Anne Vitart, and Michael Waldberg. Robes of Splendor: Native American Painted Buffalo Hides. New York: New Press, 1993.

Hudson, Ralph. “Art In Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 3 (Winter 1944): 299–350.

Jackson, Jerma A. Singing in My Soul: Black Gospel Music In a Secular Age. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Lankford, George E. Bearing Witness: Memories of Arkansas Slavery Narratives from the 1930s WPA Collections. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Marren, Susan. “Black Life in Postwar Little Rock: The Photography of Ralph Armstrong.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 63 (Autumn 2004): 233–260.

Masterson, James. Arkansas Folklore. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1974.

Miller, James W., ed. In the Arkansas Backwoods: Tales and Sketches by Friedrich Gerstäcker. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1991.

Patterson, Ruth Polk. The Seed of Sally Good’n: A Black Family of Arkansas, 1833–1953. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1985.

Randolph, Vance. Ozark Folksongs. 4 vols. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1980.

Rafferty, Milton, ed. Rude Pursuits and Rugged Peaks: Schoolcraft’s Ozark Journal, 1818–1819. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1996.

Roy, F. Hampton, Charles L. Thompson and Associates: Arkansas Architects, 1885–1938. Little Rock: August House, 1983.

Stuart, Ruth McEntery. Simpkinsville and Vicinity: The Arkansas Stories of Ruth McEnery Stuart. Edited by Ethel C. Simpson. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1983.

Thanet, Octave. By the Cypress Swamp: The Arkansas Stories of Octive Thanet. Edited by Michael B. and Carol W. Dougan. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1980.

Welky, Ali, and Mike Keckhaver, eds. Encyclopedia of Arkansas Music. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2013.

Williams, C. Fred. “The Bear State Image: Arkansas in the Nineteenth Century.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 39 (Summer 1980): 99–111.

Williams, Leonard, ed. Cavorting On the Devil’s Fork: The Pete Whetstone Letters of C. F. M. Noland. Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1979.

Wolf, John Quincy. Life in the Leatherwoods. Little Rock: August House, 1988.

Robert B. Cochran

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Maya Angelou

Maya Angelou  Arkansas Repertory Theatre

Arkansas Repertory Theatre  Arkansas Traveler by Edward Washbourne

Arkansas Traveler by Edward Washbourne  "Arkansas Traveler"

"Arkansas Traveler"  Bernie Babcock

Bernie Babcock  "The Battle of New Orleans," Performed by Jimmy Driftwood

"The Battle of New Orleans," Performed by Jimmy Driftwood  "Big Bill Blues," Performed by "Big Bill" Broonzy

"Big Bill Blues," Performed by "Big Bill" Broonzy  "Bring Me to Life," Performed by Evanescence

"Bring Me to Life," Performed by Evanescence  Dee Brown

Dee Brown  Bob Burns with Bazooka

Bob Burns with Bazooka  Caddo Dancers

Caddo Dancers  Claybrook Tigers

Claybrook Tigers  "Fattening Frogs for Snakes," Performed by "Sonny Boy" Williamson

"Fattening Frogs for Snakes," Performed by "Sonny Boy" Williamson  John Gould Fletcher

John Gould Fletcher  "Folsom Prison Blues," Performed by Johnny Cash

"Folsom Prison Blues," Performed by Johnny Cash  Alice French

Alice French  Louis Freund

Louis Freund  "The Great Divide," Performed by Point of Grace

"The Great Divide," Performed by Point of Grace  "I Want to Be a Cowboy's Sweetheart," Performed by Patsy Montana

"I Want to Be a Cowboy's Sweetheart," Performed by Patsy Montana  Jacob Wolf House

Jacob Wolf House  "Jim Dandy," Performed by Black Oak Arkansas, Featuring Ruby Starr.

"Jim Dandy," Performed by Black Oak Arkansas, Featuring Ruby Starr.  Fay Jones

Fay Jones  Scott Joplin

Scott Joplin  Mary Lewis

Mary Lewis  Niehues Basket

Niehues Basket  "Night," Performed by Florence Price

"Night," Performed by Florence Price  Fent Noland

Fent Noland  "Ol' Man River," Performed by William Warfield

"Ol' Man River," Performed by William Warfield  Ozark Folk Center

Ozark Folk Center  Dick Powell

Dick Powell  "The Most Beautiful Girl in the World," Performed by Charlie Rich

"The Most Beautiful Girl in the World," Performed by Charlie Rich  "Rock Me," Performed by Sister Rosetta Tharpe

"Rock Me," Performed by Sister Rosetta Tharpe  "Your Love is Like a Cancer," Performed by Son Seals

"Your Love is Like a Cancer," Performed by Son Seals  Soldier with Two Girls in Polka Dot Dresses

Soldier with Two Girls in Polka Dot Dresses  William Grant Still

William Grant Still  Edward Stone

Edward Stone  "Sweet Home Chicago," Performed by Robert Lockwood Jr.

"Sweet Home Chicago," Performed by Robert Lockwood Jr.  There's a Star Spangled Banner Waving Somewhere

There's a Star Spangled Banner Waving Somewhere  Charles Thompson

Charles Thompson  Thorncrown Chapel

Thorncrown Chapel  Phonnie Trent

Phonnie Trent  Jimmy Wakely

Jimmy Wakely  Watermelon Girls

Watermelon Girls

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.