calsfoundation@cals.org

Elementary and Secondary Education

Education has been evolving since the first humans arrived in Arkansas. By the late nineteenth century, as Americans became enamored with modernization, active programs of state-funded schools were looked upon as vital necessities. Since many Arkansans did not share these modernizing values, a state commitment to education lagged significantly behind the rest of the nation. Largely agrarian Arkansans remained unconvinced that tax-supported education was worth the cost, and the end of racial segregation produced a cultural crisis witnessed across the nation. By the 1990s, some evangelical Christians began sending their children to church-related schools or practiced home-schooling in response to what they saw as the failure of Arkansas’s public schools.

Pre-European Exploration

Education started in Arkansas with the arrival of the first nomadic hunter-gatherers. These Paleoindians possessed a level of education by the time they reached Arkansas that allowed them to identify and use edible and medicinal plants, and enabled them to deploy their stone-age technology in hunting. These skills were passed down through forms of instruction that constituted educational systems.

European Exploration and Settlement

Hernando de Soto arrived in Arkansas in 1541 and brought soldiers, carpenters, and priests but no school teachers. By the time French explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet arrived in 1673, once populous eastern Arkansas had been mostly abandoned save for the Quapaw tribe located near the mouth of the Arkansas River.

French agricultural settlement began in the 1720s, but the population stayed too small to support formal European-style classroom education. The European population mostly consisted of hunters, and children learned hunting skills in the same ways the Native Americans had. Not all the hunters were illiterate, however. In their dealings with merchants, it was advantageous to be able to read and calculate sums. The first known survey indicative of literacy dated from 1796 to 1797. Parish priest Pierre Janin found only ten of forty-eight godparents who could sign their names to baptismal certificates. No formal schools seem to have operated at Arkansas Post (Arkansas County), although the occasional resident priests offered some instruction. Merchant François Ménard sent his illegitimate daughter, Constance, to the Ursuline Convent school in New Orleans, Louisiana, and at least one other Arkansas girl (Marie Felicité Vallière de Vaugine) was educated there.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

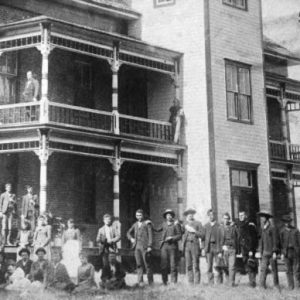

The United States’ control of the region following the 1803 Louisiana Purchase changed little, except that the Sisters of Loretto established a convent school at Pine Bluff (Jefferson County). Tradition assigns the role of the first American teacher in Arkansas to Caleb Lindsey, whose school in 1820 was located in a cave at what is now Ravenden Springs (Randolph County). Arkansas’s growth began in earnest when it became a separate territory in 1819. Members of the elite who secured government jobs were often highly educated themselves and sought education for their children. Hence, individual schoolteachers found work. Daniel Witter, a future judge and historian, opened a school in Hempstead County in 1822. Jesse Brown’s academy in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1825 was the most substantial and enduring. Allen M. Scott taught a “standing school” (one with a permanent location and teacher) at Cane Hill (Washington County). The other educational model was for a community to erect a building and then hire a teacher when demand and money became available. Sessions at many of these schools lasted only for a short time, for term length was very irregular. Often, classes started out large, but if students were needed for work or other matters, the term might end abruptly.

For many young men, teaching school was only something to dabble in before settling into a regular profession, usually the law. Albert Pike gave up teaching to become editor of the Arkansas Advocate and then became one of the nation’s leading authorities on Indian law. The practice of teachers looking for jobs was eventually replaced by local patrons looking for teachers. There was no prescribed system, and manner of instruction varied from “blab” schools, where everything was done verbally, to those that relied on at least a few graded books. Some that graduated from these unorganized forms of education went out of state for further study.

Two important factors emerged as the cotton frontier brought planters into the state. Those who settled along the Mississippi River often could afford to hire a private teacher, but really good men preferred the greater profits to be had from running their own schools. For instruction beyond the primary level, planters sent their children to quality schools at Louisville, Kentucky; St. Louis, Missouri; Memphis, Tennessee; or New Orleans. For boys, this meant a rigorous classical education; for girls, considerable instruction in the social graces figured prominently, although not necessarily to the exclusion of Latin and Greek, mathematics, history, English, and the sciences.

Some of these schools operated in Arkansas. Helena (Phillips County) boasted the services of Alexander G. Underwood, who promised education for both boys and girls in “the different branches of English education, Geography, Arithmetic, History, and such other branches of education as he thinks himself capable of teaching.” Round-earth geography was for a century highly controversial, and some schools advertised their radicalism by announcing the use of globes.

Elsewhere, local academies arose to fill the needs. One of the earliest in the southwest was at Spring Hill in Hempstead County; the Female Academy there, built at a cost of $5,000, went into operation in 1836 under the direction of Elizabeth Pratt, a professional teacher from New York. This area was home to an aristocratic planter class. In addition to fine arts and social skills, the Spring Hill school taught geography “with Globes” and the regular academic curriculum of rhetoric, composition, logic, and sciences. An academy for males soon arose next to it, but during the 1840s, hard times led to the schools’ abandonment. Health, or rather the lack of it (malaria was common at the time), seems to have played a role in Spring Hill’s decline, and Washington and Lewisville, both in Hempstead County and better situated on the Southwest Trail, took its place in the region.

Also located in southwest Arkansas was a school in Dallas County named for its first principal, Madame d’Estimauville de Beau Mouchel. She had come to Arkansas and attempted a finishing school in Little Rock before relocating farther southwest. However, her principal claim to fame was in being the castoff—and pregnant—mistress of Solon Borland, then a Little Rock editor and subsequently a Mexican War hero and U.S. senator. She left the state with her baby after Borland married in May 1845. Her school survived, and the village named for her then took the name of Tulip. During the 1850s, there arose next to it the short-lived Arkansas Military Institute.

Male teachers ran into difficulties as well. One Little Rock teacher, Ralph Goodrich, who had dared to discipline one of Governor Henry Massie Rector’s children, was physically assaulted by the irate parent. A common rule in rural districts throughout the nineteenth century was that the teacher got paid only after the session was firmly established. On the first day of classes, students would barricade themselves in the building, forcing the teacher to fight his way in. At that point, a session was said to have begun.

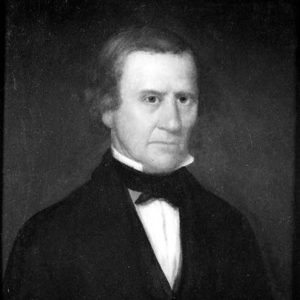

There were two educational centers in northern Arkansas. Both Fayetteville (Washington County) and Batesville (Independence County) were home to the most advanced academies. The most ambitious early antebellum attempt was the legislatively chartered Far West Seminary. The founder and chief promoter was the highly distinguished educator and Presbyterian minister, Reverend Cephas Washburn. Religious prejudice worked against the school, and political opponents helped undermine its financial support. A fire added to its woes. The final blow was the collapse of Arkansas’s banks that marked the beginning of a prolonged economic depression. Despite high hopes, the school never opened. In 1845, Robert M. Mecklin established the Ozark Institute on the site.

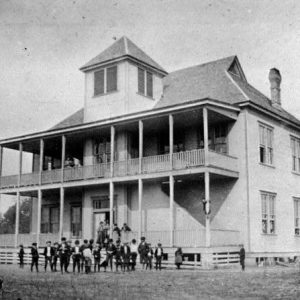

Washburn earlier had been associated with Dwight Mission, a school set up near the future site of Russellville (Pope County) in 1822 to serve the Arkansas Cherokee. In addition to the standard educational courses, the school also taught mechanical and domestic skills; the goal was to Americanize the students. It only remained in operation in Arkansas until the Treaty of 1828, when the Cherokee gave up their Arkansas lands and were pushed farther west.

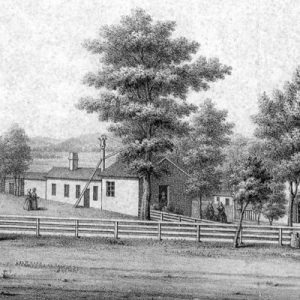

Sophia Sawyer was another early missionary to the Cherokees. Her instructional career took her from Georgia into Indian Territory. In 1839, she established the Fayetteville Female Seminary in Washington County. Sawyer was a contentious and difficult individual, but the school grew rapidly prior to her death in 1854. She acted in the face of local white hostility to Indians, whom she also educated at her school; she once received a letter with “pictures and language of impurity that I had supposed no human being capable of communicating.” Her students came not only from Indian Territory but also from Missouri and Arkansas.

Education did not improve when Arkansas became a state in 1836. The federal grant that accompanied statehood transferred to Arkansas what was styled the Sixteenth Section Lands. The sixteenth section (out of the thirty-six) from each township was set aside (withheld from public sale) to support education. These lands amounted to about one million acres. At first, federal law permitted state or local authorities only to rent or lease these lands. However, Congress later responded to the clamor of the speculators and modified the law so as to permit their sale. A number of states, including Mississippi and Wisconsin, held on to their lands, but Arkansas did not.

Enacting a state system did not engage legislators until 1843, and then with a law that, had it been implemented, would have resulted in 5,800 officials. Land was so plentiful that, at the then-current price of two dollars an acre, the result of a sale would have been $1,280, giving an annual interest of $128. After the federal government permitted the lands to be sold, most of the land was sold off in fractions of a section, often to school board members. Squatters claimed some of the land, and the population was too scattered to provide enough students to justify trying to build a building and hire a teacher. Hence, the subscription system dominated prior to the Civil War. When enough families promised money, a term of school would be held. The state purchased a collection of outdated textbooks and, in 1853, established a state commissioner of education, but the commissioner could not even get counties to file reports on their student populations and funding. Census data from 1860 revealed that a quarter of the state’s adults were illiterate and that only half the children were in school. Of these, half were in some form of public school, with the other half in private facilities. The most common arrangement was for the community to erect one building that served as both church and school. The leading Protestant denominations shared the building, resulting in the name “Union” being applied.

Another aspect of statehood was the Seminary Lands. At the onset of statehood, the federal government gave Arkansas seventy-two sections of land with which to start a seminary of higher education. The first governor, James Sevier Conway, told the state legislature that establishing a university was one of its important duties, but aside from some hot oratory about colleges nurturing an aristocracy, nothing was done until Reconstruction. The money from the sale of these lands went to other purposes. Governor John Selden Roane addressed these matters in 1853, observing that Arkansas did not have either the population to support common schools or an institution to train teachers for the time when they would be needed.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

The Civil War brought education at all levels to a virtual standstill. The academies closed as teachers and students went off to war. The Fayetteville Female Seminary was burned by Confederate general Ben McCulloch’s retreating troops. St. Johns’ College served as a hospital as well as the site for former student David O. Dodd’s hanging for spying on January 8, 1864. Virtually the only functioning institution was Reverend Samuel Stevenson’s Paraclifta Seminary located in the extreme southwest corner of the state. Home-schooling became the order of the day, and older children taught their younger siblings.

The end of slavery, starting with General Samuel Curtis’s invasion in the spring of 1862, created a major philanthropic challenge for groups wishing to aid the freed people. As the Union armies emptied the plantations of slaves, and camps of freed men and women arose near the garrison towns, Northern missionaries arrived, opening Sabbath schools and providing elementary education—sometimes in integrated settings. The American Missionary Association and the Indiana Yearly Meeting of Friends (“Quakers”) supported these efforts, which were later incorporated into the Freedmen’s Bureau, a federal program of relief and resettlement. By 1867, nineteen day and five night schools were in operation. Twenty-six of the teachers were white, three were African American, and a total of 1,296 students ranging from the very young to the very old were enrolled.

The Union government organized under the Constitution of 1864; while it abolished slavery, it did not enfranchise freed people. In education, state aid went only to white schools. This constitution proved to be short-lived, and a new constitution, written in part by black citizens and adopted by their votes, came into being in 1868. W. H. Gray, a black Phillips County delegate, blamed the existence of racism on lack of education and argued that if African Americans were given the franchise and educational opportunity, the obstacles to progress would vanish. However, the ex-Confederate paramilitary arm, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), targeted teachers, especially those in the former Freedmen’s Bureau schools, who were often active Republicans.

Legislation adopted in 1868 divided the state into ten districts, each administered by a superintendent who was responsible for licensing teachers and supervising the schools. The first meeting of the State Teachers Association (STA) took place on July 2, 1869, with Dr. Thomas Smith, the state superintendent of education, as president. Its Arkansas Journal of Education became the first in a series of state organs that hashed over the sorry state of Arkansas’s education. Most of these first teachers were from the North, and while there was professionalism at the tutorial level, some of the ten superintendents were political hacks. By 1870, the state had 88,585 white and 19,280 black students in classrooms, but the greatest problem was that teachers were being paid in much-depreciated warrants, a systemic problem that continued until about 1970. Since contracts were from and through the counties, warrants—pictorial promises to pay—were redeemed only when the county had collected taxes. Teachers either had to hold their paychecks for months or accept an offer, greatly discounted, to get ready money. Hence, for more than a century, the official salary given teachers, which usually ranked among the last three states in the nation, did not correspond at all to the amount they actually received.

The Constitution of 1874 that ended Republican Reconstruction contained a mandate for “a general, suitable, and efficient system of free schools, whereby all persons in the state between the ages of six and twenty-one may receive gratuitous education.” Local white opposition to property taxes and a collapsing economy in the wake of the Panic of 1873 contributed to an anti-tax movement that targeted education. Therefore, the constitution ordained that the state could devote no more than three mills of the property tax to schools. By 1876, two years after the Democrats regained control of the state, only 15,890 students were enrolled, and black schools in particular were hit by what one missionary called the “starvation plan.” Working to minimize these dislocations was the Peabody Education Fund, created by George Peabody.

The dark age period of public education from 1874 into the early twentieth century was lit only by the missionary work of a number of memorable individuals. James L. Denton, who served as state superintendent of education until his suicide in 1883, orated constantly to keep hope alive and education issues before the public. Rodney H. Parham, a former Confederate major, whose involvement lasted into the twentieth century, provided Southern legitimacy to what many considered a dangerous Northern innovation. Ida Joe Brooks, the daughter of Republican leader Joseph Brooks, was superintendent of Little Rock High School when she served as STA president in 1878, reportedly the first woman in America to head a state teachers’ organization. Josiah Hazen Shinn, who also wrote a state history and was an active journalist, promoted normal schools (schools to train teachers) and suggested that all teachers be required by law to be STA members. Junius Jordan, who had run his own academy and served as state superintendent in 1894, started summer normal school sessions in the absence of a state teacher training school.

Virtually every stage of progress depended first on Peabody money and then on reluctant support from the legislature. Academies, which had opened in the wake of the Civil War, dominated the educational scene during these years. Reverend A. R. Winfield, who inserted himself into politics, using total prohibition of alcohol as his benchmark, openly attacked public schools, which he would support only if the church (presumably his own Methodist Church, South) could control them.

Finally, the Deaf Mute Institute became a state institution after the Civil War, although it was shut down temporarily due to a lack of funds in 1875. The School for the Blind, chartered by the state in 1859 in Arkadelphia (Clark County) and then moved to Little Rock after the Civil War, suffered an equally tenuous existence.

Early Twentieth Century

One of the most troubled issues in the late nineteenth century was the lack of proper teacher training. Most states had normal schools, but Arkansas lacked such a school until 1907 when a two-year institution, Arkansas State Normal College (now the University of Central Arkansas), was established in Conway (Faulkner County).

In place of the centralized administration the Republicans had established, Arkansas education after 1874 operated in a near state of anarchy. Local patrons who decided they wanted a school carved out a district and set one up. “Chicken gizzard,” one of Craighead County’s seventy-seven districts, was so called because its appearance was the result of earlier districts taking all the best parts. Since indebtedness was not permitted and state support as late as 1903 amounted to $4.33 per pupil, erection of a building precluded having enough money to pay teachers. Arkansas’s salary rate, $34.46 a month, was far behind the nearly $60 paid in states to the west. Teachers often doubled as correspondents for county weekly newspapers. Male dominance in the profession, which had been reasserted after 1874, began to erode after 1900, because many men used teaching only as a part-time job while pursuing a regular college degree. Turnover was so great that one student recalled having had ten different teachers in thirty months. Often, the school building continued to double as a church, with the result that funerals sometimes closed the school. Denominational objections denied Jackson County’s Surrounded Hill school from having a piano or organ.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the extreme localism, school board elections were hotly contested. Nepotism and favoritism, combined with an almost total absence of professionalism, remained hallmarks of many local districts. One-room schools in the poorest districts remained of log construction, and high schools were limited to the larger towns. Parents who wished to see their children educated went to great sacrifices, including moving into progressive areas with strong schools, arranging for children to board with a relative or friend so that they could attend town schools, and even sending their children out of state to be educated.

The Progressive Era, a time of radical transformation in American education, began in Arkansas only after Governor Jeff Davis, a foe especially of black education, moved on to the U.S. Senate in 1907. The McFerrin Amendment in 1906 allowed voters to raise the millage rate, but opposition to taxes limited its effectiveness. The passage of the first compulsory school attendance law in 1909 meant little since it was optional for the counties; naturally, most rural counties (especially in the Delta) opted out of the law. In 1917, only 446,525 of the state’s 649,083 school-aged children were enrolled, and only 292,413 attended regularly. Nevertheless, high schools received state aid in 1911, vocational education funding from the federal government arrived in 1917, and membership in the Arkansas Teachers’ Association (the former STA) had risen from 150 in 1900 to 1,500 in 1915. Amendment 11 (the Eighteen-Mill District School Tax), adopted in 1926, allowed districts to tax up to the new limit. “Better Roads to Better Schools,” the political slogan of Governor John E. Martineau in 1926, reflected the ethos of the 1920s. Road construction came first, though, and by 1932, the state’s per capita debt was the highest in the nation.

In rural areas, the split term, whereby students attended only during the winter and in July and early August, remained the norm; seventeen counties had no high schools at all, and in no county were high schools available for all children. Advanced educational opportunities for black students were virtually nonexistent, and the entire educational system was infected with racism. In Mississippi County, a hardly mysterious fire claimed the new school that planter Robert E. Lee Wilson had built for his black tenants. Statewide, only 1.8 percent of school-aged black students attended high school. State money earmarked for black schools was regularly diverted to white schools, a practice that, by 1948, cost black schools more than one million dollars annually. Indeed, central to the creation and survival of black schools was outside money. The John L. Slater fund, the oldest, began distributing money in 1882; the General Education Fund, with Rockefeller support, started in 1902 and assisted with libraries and teacher training; the Anna T. Jeanes Fund supported industrial education after 1907; and the Julius Rosenwald Fund, from 1912 to 1932, aided in the construction of more than 320 black schools. The age of segregation led to the formation of the Arkansas Teachers Association, the segregated counterpart to the white body. James Carter Corbin, the principal at Branch Normal, was the first president.

One of the few positive features of the 1920s was funding for “Opportunity Schools” sponsored by the Arkansas Illiteracy Commission. Although Arkansas ranked thirty-seventh in literacy, the state was tenth in decreasing illiteracy. Anti-intellectualism, a persistent feature in Arkansas life, surfaced when Arkansas voters used the initiative process to ban any mention of Darwin or evolution from the state’s schools in 1928. Hendrix College fired evolutionist professor Edwin L. Shaver, and Baptist colleges required loyalty oaths. Even the state schools had mandatory chapel and required Sunday School attendance. What did flourish in the twentieth century was sports, first football and then basketball. For town schools, team success was used to define community prowess. While some critics insisted that academic values were being compromised, Mountain Home editor Tom Shiras argued that sports taught students how to get ahead in life.

The Great Depression paralyzed the agricultural economy and hence the property-tax base. Schools often closed, or they demanded tuition (in violation of the state constitution). Junius Marion Futrell, elected governor in 1932 on a platform of cutting government expenses, believed high schools were a waste of money. Fortunately, federal officials disagreed, and New Deal assistance stabilized the situation. In addition, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and other programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) supported both building schools and paying for teachers. Many rural schools got a WPA gymnasium/auditorium/cafeteria courtesy of the federal government, with the result that basketball games no longer had to be played on dirt floors, and gym shoes became an additional expense for parents. The expansion of the road system led to more school buses, and slowly the number of one-room school districts declined. However, no governor and few legislators would risk making education reform an issue.

World War II through the Faubus Era

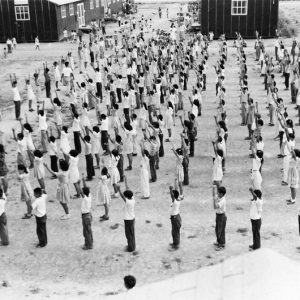

World War II created a crisis and an opportunity. Male teachers often left for the army, and many teachers took advantage of a national teacher shortage to find better-paying jobs elsewhere. Probably the best education in the state was at the relocation camps at Jerome (Drew County) and Rohwer (Chicot County), where those of Japanese ancestry had been interned during the war. Quality teachers were recruited and paid nationally competitive salaries. Not lost on the students was the irony of being taught American values of freedom and democracy while being confined behind barbed wire.

The evident weaknesses of Arkansas’s public schools after 1946 did not influence the legislature. It was voters who forced consolidation in Initiated Act No. 1 in 1948. In 1948, 424 districts were made from the 1,589 of a year earlier. However, non-compliance was widespread. A 1966 report later indicated thirty-one districts still did not offer twelve years of schooling, and in at least three cases, schools that had consolidated to meet the law de-consolidated shortly thereafter. Although the law set the number at 350 students as the standard per district, seventy-one districts had fewer than 100 students in grades seven to twelve, and none met North Central Association (NCA) standards.

Although Governor Sidney McMath acted to end the diversion of black school funds to white schools, readers of Life magazine read about and saw conditions in West Memphis (Crittenden County), where white residents had a new school but voters had rejected replacing the burned-out black school.

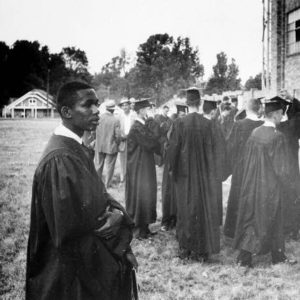

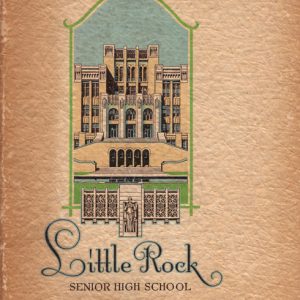

There was universal white opposition to the high court’s Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas ruling in 1954, and in 1957, Governor Orval Faubus became a hero to voters for standing up to the federal government during the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School. Thereafter, acting under one of the state’s anti-integration laws and in accordance with Amendment 44, which claimed to nullify Brown v. Board of Education, Little Rock voters shut down their schools for one school term. Although the state lost its cases in federal courts, little real integration took place until the early 1970s.

Desegregation invariably meant that African-American students now had to attend the white schools. In Jonesboro (Craighead County), the newest school building had housed the black students, but it stood abandoned because white parents refused to allow their children to go to a former black school for fear the students would catch syphilis. Other victims of desegregation were black administrators and teachers, who were rarely taken into the unified systems. In Delta regions with high black student enrollment, white residents put their children in private academies. Many had nominal Christian affiliations. At first, some of these schools would not accept black students, but faced with federal discrimination lawsuits, these restrictions were abandoned. White voters then often opposed any attempt to increase the public school millage rate, leaving the virtually all-black public schools starved. One of these poorly funded districts, Lake View in Phillips County, eventually filed an important lawsuit against the state’s educational funding formula.

Modern Era

Modernization of public education in the last quarter of the twentieth century was controversial. Stories of incompetence were widespread, including one of a teacher who mistakenly taught students about World War Eleven (II). Every governor faced the issue, but one, Bill Clinton, made it a dominating issue that served as a springboard to his presidency. Clinton began by making a thorough study of the problem—too many districts, too little pay. By the 1980s, some teachers were receiving food stamps, and their children were eligible for free lunches. A one-percent increase in the state’s sales tax financed the plan, the most controversial part of which was testing the teachers for their competency. What Clinton began was soon matched by other states, but Clinton had the benefit of being known both as the education governor and as one who stood for accountability even at the cost of teacher support.

The next phase came in response to the last of the repeated rulings by the state Supreme Court that the existing system violated the state constitution. In Lake View District No. 25 v. Huckabee (2002), the court ruled unequivocally that inequality was unconstitutional and that the legislature must fix the problems in accordance with the decision under court supervision. The state was badly divided over implementing this decision as smaller districts fought back legislatively to prevent consolidation. Adding to the controversy was the federal “No Child Left Behind” law. In Arkansas, twenty-nine percent of the schools failed the federally mandated test and thus were threatened with takeovers or being shut down.

Some parents—in response to forced integration, a desire for better educational quality, a fear of secularism, and other reasons—now turned to private and church-sponsored schools and home-schooling. Many religious schools promised rigorous education often explicitly free from secularism and implicitly free from race mixing. Home-schooling by 2005 was virtually unregulated. There was much enthusiasm for charter schools that would be free from bureaucratic control. A reinterpretation of the teaching profession had also taken place. The Arkansas Education Association, as the former STA was called after 1920, was by 2000 constantly referred to in the press as a “union,” a term intended to denigrate teachers both professionally and financially.

In March 2023, Republican governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed into law the LEARNS Act, which she described as “the most far-reaching, bold, conservative education reform in America.” The broad bill affects multiple aspects of the state’s education system, including teacher pay, per-student funding (in the form of vouchers for private schools), graduation requirements, and student testing. Critics argue that the law will drain money and resources from public schools, exacerbating economic inequality.

Conclusion

Arkansas had long possessed what by national standards consisted of a backward educational environment. One element was a lack of professionalism, a condition often apparent in high school social studies classes too often taught by uncaring and under-trained coaches. Science instruction, especially in biology, frequently yielded to community pressure, with the result that evolution information was often not taught. Ironically, it was Arkansas that provided in Epperson v. Arkansas (1968) the case in which the Supreme Court stuck down anti-evolution statutes. A legislative attempt to mandate teaching “creation science” came to grief in district court with the case McLean v. Arkansas Board of Education (1982).

A review of the addresses made by Arkansas’s governors since 1836 reveals that educational issues ranked along with economic development as the most consistently discussed topics. However, discussion has not led to solutions.

For additional information:

Arnold, Morris S. Colonial Arkansas: A Social and Cultural History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

Blevins, Brooks. “Mountain Mission Schools in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 70 (Winter 2011): 398–428.

Cantu, D. Antonio, and Roger Lambert. Early Education in the Arkansas Delta. Chicago: Arcadia, 2001.

Carter, Deane G. “Some Historical Notes on Far West Seminary.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 29 (Winter 1970): 345–360.

Clement, R. Davis, II. “Education Reform as Moral Disengagement: The Racist Subtext of the State Takeover of the Little Rock School District.” PhD diss., College of William and Mary, 2018.

Donato, Rubén, and Jarrod Hanson. The Other American Dilemma: Schools, Mexicans, and the Nature of Jim Crow, 1912–1953. New York: State University of New York Press, 2021.

Dwinal, Mallory A. “Teach for America and Rural Southern Teacher Labour Supply: An Exploratory Case Study of Teach for America as a Supplement to Teacher Labour Policies in the Mississippi-Arkansas Delta, 2008–2010.” DPhil diss., University of Oxford, 2012.

Finley, Randy. From Slavery to Uncertain Freedom: The Freedmen’s Bureau in Arkansas, 1865–1869. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1996.

Harding, Thomas. One-Room Schoolhouses of Arkansas as Seen through a Pinhole. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

Harwood, Bill, and Grace Hardwood. School Days: Contemporary Views on Arkansas Public Education. Little Rock: Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation, 1978.

Johnson III, Ben F. “‘All Thoughtful Citizens:’ The Arkansas School Reform Movement, 1921–1930.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 46 (Summer 1987): 105–132.

Jones, Jeanne E. “The First Forty Years of Education: Common Schools in Independence County, 1829–1869.” Independence County Chronicle 33 (April–June 1992): 37–51.

Kennedy, Thomas C. “Southland College: The Society of Friends and Black Education in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 42 (Autumn 1983): 207–238.

Ledbetter Jr., Cal. “The Anti-Evolution law: Church and State in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 38 (Winter 1979): 299–327.

Ledbetter Jr., Calvin R. “The Fight for School Consolidation in Arkansas, 1946–1948.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 65 (Spring 2006): 45–57.

Luck, H. D. Arkansas Higher Education, 1971–1995. San Antonio, TX: The Watercress Press, 1996.

McNamee, Heather. “The Road to Respect: African Americans and the Fight for Equal Education in Jonesboro, Arkansas since 1920.” PhD diss., University of Memphis, 2022.

Moffatt, Walter. “Arkansas Schools, 1819–1840.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 12 (Spring 1953): 91–105.

Patterson, Thomas E. History of the Arkansas Teachers Association. Washington DC: National Education Association, 1981.

Pearce, Larry Wesley. “The American Missionary Association and the Freedmen in Arkansas, 1863–1878.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 30 (Summer 1971): 123–144.

———. “The American Missionary Association and the Freedmen’s Bureau in Arkansas, 1866–1868.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 30 (Autumn 1971): 242–259.

———. “Enoch K. Miller and the Freedmen’s Schools.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 31 (Winter 1972): 305–327.

Penton, Emily. “Typical Women’s Schools in Arkansas before the War of 1861–1865.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 4 (Autumn 1945): 325–339.

Reynolds, J. D. “Seminary Land Grant.” Publications of the Arkansas Historical Association 3 (1911): 256–266.

Simpson, Roy. “Reminiscences of a Hill County School Teacher.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 27 (Summer 1968): 146–174.

Smith, C. Calvin, and Linda Walls Joshua, eds. Educating the Masses: The Unfolding History of Black School Administrators in Arkansas, 1900–2000. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Stinnett, T. M., and Clara B. Kennan. All This and Tomorrow Too: The Evolving and Continuing History of the Arkansas Education Association, a Century and Beyond. Little Rock: Arkansas Education Association, 1969.

Tieken, Mara Casey. Why Rural Schools Matter. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Weeks, Stephen B. History of Public School Education in Arkansas. United States Bureau of Education Bulletin 27. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1912. Online at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED543051.pdf (accessed September 9, 2020).

Wheeler, Elizabeth L. “Isaac Fisher: The Frustrations of a Negro Educator at Branch Normal College, 1902–1911.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 41 (Spring 1982): 3–50.

Wynn, Xavier Zinzeindolph. “The Development of African American Schools in Arkansas, 1868–1963: The Operation of Black and White Schools with Regards to Funding and the Quality of Education.” EdD diss., University of Mississippi, 1995.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Albert Pike School

Albert Pike School  Arkansas School for the Deaf

Arkansas School for the Deaf  Blackton School

Blackton School  Floyd Brown

Floyd Brown  Calico Rock Church and Oddfellows Hall

Calico Rock Church and Oddfellows Hall  Central High School

Central High School  Clarke's Academy

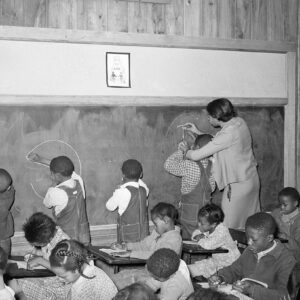

Clarke's Academy  Colored Industrial Institute

Colored Industrial Institute  Dunbar High School Postcard

Dunbar High School Postcard  Dwight Mission

Dwight Mission  Elizabeth Eckford Denied Entrance to Central High

Elizabeth Eckford Denied Entrance to Central High  El Dorado High School

El Dorado High School  Susan Epperson

Susan Epperson  Susan Epperson

Susan Epperson  Fargo Agricultural School

Fargo Agricultural School  Fargo Agricultural School

Fargo Agricultural School  Fayetteville Female Seminary

Fayetteville Female Seminary  Gravette High School

Gravette High School  Ernest Green

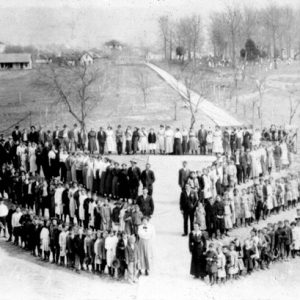

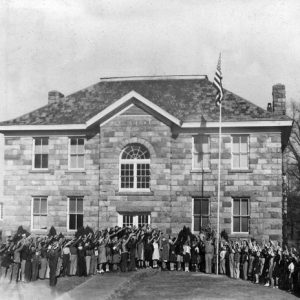

Ernest Green  Harrisburg School Children

Harrisburg School Children  Hoxie Glee Club

Hoxie Glee Club  Jerome Relocation Center School Children

Jerome Relocation Center School Children  Lakeview Students

Lakeview Students  Little Rock Nine Monument

Little Rock Nine Monument  Little Rock Senior High Yearbook

Little Rock Senior High Yearbook  Lost Year Student

Lost Year Student  Lowell School

Lowell School  Lutheran Schools Parade

Lutheran Schools Parade  Marshall School

Marshall School  Lillian McDermott

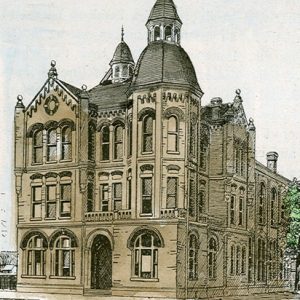

Lillian McDermott  Merrill Institute

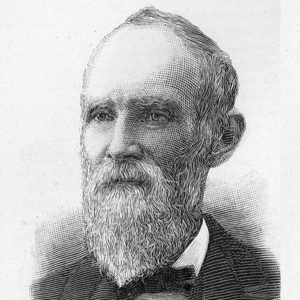

Merrill Institute  Joseph Merrill

Joseph Merrill  Monastery and Order of Our Lady of Charity

Monastery and Order of Our Lady of Charity  Mount Ida High School

Mount Ida High School  Pleasant Springs School

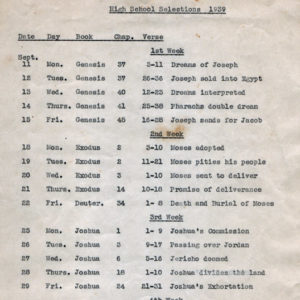

Pleasant Springs School  Public School Bible Verses List

Public School Bible Verses List  Carrie Shepperson

Carrie Shepperson  Stamps High School

Stamps High School  Charlotte Stephens

Charlotte Stephens  Subiaco Abbey

Subiaco Abbey  Surrounded Hill School

Surrounded Hill School  Minnijean Brown with Classmates

Minnijean Brown with Classmates  Vilonia High School

Vilonia High School  Cephas Washburn

Cephas Washburn  Woodruff School

Woodruff School

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.