calsfoundation@cals.org

Health and Medicine

Arkansas long had a reputation for being sickly because much of the state supported large mosquito populations, carrying malaria, yellow fever, and other diseases. Modern medicine, a largely nineteenth-century creation, arrived late, and throughout the twentieth century, diseases eradicated elsewhere continued to flourish. Only after World War II did sharp improvements in health occur, but the Delta lagged far behind. Problems in health and medical programs were compounded in part because many Arkansans deliberately engaged in forms of risky behavior such as tobacco use and unhealthy diets.

Prehistoric Arkansas

The first settlers more than 10,000 years ago brought to the New World only a few major illnesses. One was tuberculosis, evidence of which is visible in bones from burial sites. Open-air living limited the impact of this potentially devastating disease. Modern research shows that the first Arkansans, the Paleoindians, were the healthiest, having a balanced diet of roots, fruits, and fresh meat or fish. Their migratory practices limited the gastrointestinal disorders that came with settled populations. By the Mississippian Period, agriculture flourished, imposing an unbalanced diet of corn and beans on the lower classes, sometimes resulting in pellagra, a disease that later affected lumber and mining communities in the nineteenth century. Evidence of iron deficiency (anemia) has been uncovered in eastern Arkansas.

Sickness was sufficient to produce a class of persons to treat it. Called jongleurs by the French (for they also practiced juggling and magic) and “medicine men” by the Anglo-Americans, these native shamans combined religious incantations with a sophisticated application of herbs and techniques such as sweat baths (vapors). Closely connected was the practice of visiting the springs in what is now Hot Springs (Garland County).

Prehistoric Indians were unequipped genetically with resistance to the Euro-African disease pool that first came to Arkansas with Hernando de Soto in 1541. The subsequent virtual abandonment of Arkansas that French explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet noted in 1673 could have come about through smallpox, but malaria had arrived as well, putting all Delta peoples at risk. Abandonment may have been gradual rather than dramatic.

The Colonial Period

French settlement began at Arkansas Post in 1686, and reports of sickness appeared constantly in official reports as well as travelers’ journals. There was supposed to be a post surgeon. At least one resident, François Menard, had studied medicine in France but was best known as a merchant, and the post’s garrison and population were too small to support a formally trained physician. The affluent went to New Orleans for medical services.

Sicknesses were common among the newcomers, but the various tribes fared far worse. The Quapaw were hit repeatedly by smallpox after 1698. From perhaps 20,000 in 1600, their numbers fell to 215 by the end of the nineteenth century. Through intermarriage with Europeans, some immunity could be obtained. Contact with Europeans undermined native cultures, predisposing many to alcoholism, which made tuberculosis worse. Respiratory diseases, notably influenza, affected both Europeans and tribes. The biggest and still unsettled controversy concerns syphilis, a venereal disease that became a massive public health problem soon after the discovery of the New World. Other disease include scurvy (vitamin C deficiency), yaws (a skin disease from Africa), diphtheria (sore throat), dysentery, and typhoid fever.

The Antebellum Period

At least one doctor may have arrived prior to the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. Charlatans, as French and Spanish authorities described non-degreed alleged doctors, grew in importance, in part because they were more willing to embrace Indian practices. In the new republic, medical licensing was viewed as aristocratic. Contending “schools” arose, with chiropractic and osteopathy being modern descendants of earlier divergent medical paths. Practitioners were family members, Native Americans, well-meaning tradesmen, slaves, woodsmen, and preachers. Many could handle broken bones, snakebites, gunshot wounds, or arrows embedded in bone or muscle. Fevers were often beyond them, and even the most experienced midwives could not cope with obstetrical complications. Maternal and infant deaths were frighteningly common.

The disease-ridden lowlands lured settlers due to their rich agricultural lands, but many fled from the Arkansas River bottoms to the highlands. One minor improvement came in 1821 when the seat of government moved from Arkansas Post (Arkansas County) to Little Rock (Pulaski County). Doctors, surprisingly, were plentiful. A few of them can be identified: Robert F. Slaughter of Arkansas Post, Peyton R. Pittman of Davidsonville (Lawrence County), Matthew Cunningham of Little Rock, Caleb S. Manley of Batesville (Independence County), N. D. Smith of Hempstead County, and Nimrod Menifee of Cadron (Faulkner County). In 1829, Little Rock had five doctors serving the 250 to 300 residents. Although the ratio fell to one doctor per seventy-eight people by 1836, many, such as Solon Borland, turned from medicine to seek their fortunes in agriculture, law, or politics.

Arkansas’s regular physicians made one major attempt to control admission to the profession. Their 1831 medical licensing bill, which admitted to practice medical school graduates and tested other applicants, was vetoed by Governor John Pope, who proclaimed that “the highest authority known in this land, public opinion,” was superior to diplomas. Unable to get state standards, doctors in Van Buren (Crawford County) established their own county body; others came after the Civil War.

Before the Civil War, three venues of medical training were available to young men. The first was apprenticeship. An established physician agreed to accept a student for a given period of time, during which the physician served as mentor and teacher. The student paid a fee and served as an assistant, borrowed books to “read” medicine, accompanied the doctor on house calls, and observed surgeries. At the end of the apprenticeship, the mentor wrote a testimonial letter, reviewing the areas of medicine mastered by the apprentice, and this letter served in many states as the only credential required for being licensed to practice medicine.

The second venue was the “proprietary school,” or a for-profit medical school, in which a group of doctors owned the school and served as faculty. Each doctor taught the subjects he knew best, and students were required to purchase tickets to a certain number of lectures for graduation. These students never saw a patient during training, and the curriculum was often inadequate, depending entirely on the professional knowledge of the owners. A diploma from a proprietary school was licensure. Although most were regular or “allopathic,” schools were established for competing disciplines.

The third venue was a university medical school. In 1830, twenty-two such institutions existed in the United States, all east of the Mississippi River and all allopathic. Allopathic physicians learned from books and lectures to take “heroic” measures of therapy, believing that any therapy that changed patients’ symptoms was working on the disease itself. Blood letting, blistering, drastic purging, and agents to induce vomiting were employed to excess. Among the medical school graduates in Arkansas in this early period were Matthew Cunningham from the University of Pennsylvania, Alden Sprague from Dartmouth College, and James A. Dibrell Sr. from the University of Pennsylvania. Benjamin F. Scull from Arkansas Post, also one of Arkansas’s first composers, studied at the Medical College of Philadelphia.

In the 1830s and 1840s, another theory of medicine, homeopathy, became widely popular in the region. A German physician with a university background, Samuel Hahnemann, taught that, if a remedy given to a healthy person could produce symptoms of disease, that remedy would cure a patient with those symptoms. Few homeopaths settled in Arkansas before the Civil War, but there were several in Little Rock at the turn of the twentieth century. All too typical was J. H. Gray at Rocky Comfort (Little River County), who doctored sick horses along with dosing out calomel, blue mass, and quinine with no medical education at all.

Doctors also competed to some extent with midwives. No organized midwifery body existed, but many women preferred the presence of female midwives during childbirth. Difficult pregnancies often led to doctors being called in at the last moment. The advantage of an obstetrics practice was that it led to a general family practice; hence, doctors bad-mouthed midwives on both general and financial principles.

Finally, people practiced self-help. One Southern medical book for the home widely used in Arkansas was Tennessean John G. Gunn’s Gunn’s Domestic Medicine, or Poor Man’s Friend (1830), which was revised and reprinted for at least ninety years. Gunn gave special attention to the needs of women. The Reverend D. L. Saunders, MD, of Little Rock authored Woman’s Own Book: Or, A Plain and Familiar Treatise on all Complaints and Diseases Peculiar to Females in 1858. Planters especially relied on books in treating their slaves, and plantations were sickly places, both for blacks and whites, largely due to their geographic location in the lowlands. A great source of misinformation came from patent medicine advertisements. Throughout the state, women—especially those with an Indian background—were called upon to supply herbal remedies.

Epidemics occasionally interrupted the normal life cycle. The Mississippi River was an artery from the disease-rich tropics to the heartland. Helena (Phillips County) was regularly threatened. Editor James M. Cleveland of the Democratic Star died in the yellow fever epidemic of 1855 as many of the town’s residents fled. Cholera accompanied the Cherokee and other tribes during their forced migrations west. Cholera and other diseases also affected parties heading to the California gold fields. This disease, which hit Fort Smith (Sebastian County) before the Civil War, was marked by extreme dehydration, but the standard textbook treatment was to deny the patient any liquids.

Civil War through Reconstruction

During the Civil War, Arkansas became part of the Confederate Department of the Trans-Mississippi, a sprawling, poorly organized area of 700,000 square miles, reaching to Arizona and New Mexico. After the frightful carnage at the Battle of Shiloh (April 6–7, 1862), a group of Confederate surgeons met in Little Rock to create an examining board to recruit physicians for the Southern army. Doctor Philo Oliver Hooper, a graduate of the Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia, practiced in Little Rock; later he would return to Little Rock, reestablish his practice, and help establish a medical school.

Medicines, especially quinine, were in short supply. Battle wounds were often compounded by fractures. Sanitary (antiseptic) practices had not yet been scientifically established, and the two forms of anesthesia, ether and chloroform, were used less than a fourth of the time. Many amputees died from shock. Nursing was only beginning to admit women; the first official female nurse, Mary Phelps, was the wife of John S. Phelps, the Union military governor of Arkansas. Post-operative care was lacking, and in towns, schools and churches were appropriated for hospitals.

The civilian population suffered malnourishment, especially in winter 1864. Cholera, which invariably followed armies, did not limit its damage to military personnel and arrived in force in 1866 and 1867. Nevertheless, the Civil War produced a medical revolution. Government studies documented medical treatment and photographed specimen patients. Organized female nursing followed, as did the building of hospitals. Two years after the war, Joseph Lister identified sepsis and brought in carbolic to fight infection.

The end of slavery had pronounced negative medical effects. The Freedmen’s Bureau found itself almost powerless while white authorities ignored the high death rate among African Americans. Left almost entirely to their own devices, most relied on “root doctors” or “conjurers.” One of the former, Patience Brooks Trotter of Monticello (Drew County), was highly regarded even by white physicians because of her successes in handling “female complaints” and cancers.

After Reconstruction, some graduates of black medical schools, notably Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, served a small part of the black population. Most located in towns, for while the needs were greater in the rural areas, patients there could not afford to pay. Little Rock, Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), Helena, Forrest City (St. Francis County), and Newport (Jackson County) were served by doctors and dentists. The customers’ poverty was reflected in the career of Dr. William D. Black, who relied on the income generated from the plantation lands of his father, Pickens Black. Dentistry was a particularly sore point, for while some white doctors would see black patients, white dentists usually refused to do so.

The Foundations of Modern Medicine, 1870–1920

The foundations for future progress started with organizing and establishing medical licensing. Shortly after the end of the war, Hooper and twelve medical colleagues organized the Medical Society of Little Rock and Pulaski County. Then, on November 21, 1870, a group of physicians from around Arkansas met at the Little Rock Pacific Hotel to establish a statewide medical society. The yellow fever panics of the 1870s spurred a state licensing law.

When yellow fever struck Memphis in 1873, Little Rock was flooded by refugees. Luckily, they did not bring the disease with them. In 1878, a Little Rock board of health sprang into operation when “yellow jack” was first reported in New Orleans. Other communities followed suit, with “shotgun” quarantines being common in small towns and rural areas. The chaos that followed prompted demands for a coordinated state policy to work with the Sanitary Council of the Mississippi River, a multi-state coordinating body. In the absence of legislative action, Governor William Read Miller appointed the Little Rock board as the de facto state body, which at least legitimized its existence and allowed it access to funds from the National Board of Health. With more than $7,500 in aid, the board in 1879 established quarantine stations to keep that year’s epidemic from expanding.

Quarantines operated both regionally and locally. As the nation’s transportation grid increased, it became increasingly difficult to block all human contact. Locally, communities set up pest houses, leaving sick people there to die. If that could not be used, a black flag outside a house warned those in not to leave and others not to come. In the case of smallpox, death was followed by the destruction of all clothing, bedding, and other property.

The existence of a temporary board of health in Arkansas dated back to 1832 in Little Rock, but the de facto board of 1879 led Arkansas into uncharted waters. Dr. Charles Nash, the 1879 president, for example, called attention to adulterated and impure foods. In 1881, the legislature did establish a state board of health, but lacking in the law were requirements for death, marriage, birth, and other statistics that had become routine elsewhere in the nation, and the funding was adequate only for a small staff.

In the absence of any outbreaks, the board became inactive until 1897, when smallpox surprised the state. Salem (Fulton County) was the center, and local doctors at first failed to recognize the disease that eventually spread across the state. Galloway College in Searcy (White County) and Beavoir College at Wilmar (Drew County) were both hit. Despite some 7,000 to 10,000 cases yearly, legislators rejected inoculations, with country doctor and long-time legislator W. H. Abington saying that they did not work.

Medical licensing legislation also dated to 1881, but this “Quack Law” grandfathered in all existing practitioners and required “doctors” only to appear before a county board, which not need even have a doctor on it, and register with the county clerk. Those utterly ignorant of medicine could go to Benton (Saline County) and appear before the Saline County Board, which between 1881 and 1891 certified 149 doctors although the entire county contained only eleven physicians.

Not only was the state overrun by incompetents, but fraud was rampant as well. Hot Springs, where the baths were a major medical drawing card, had a problem with physicians and boarding houses who hired “drummers” to steer in customers. Seriously ill persons, especially on arriving trains, were victims of these scams, and the national scandal prompted a state law in 1903 and federal legislation in 1904. A constitutional argument in favor of medical commercial freedom was rejected by the state Supreme Court in Thompson v. Van Leer (1906).

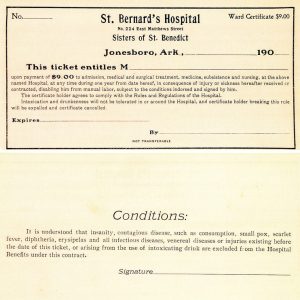

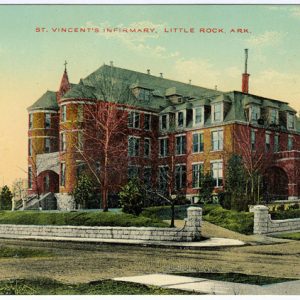

Closely connected to medical licensing was the rise of hospitals. Arkansas’s first hospital (today called Sparks Regional Medical Center) was founded in Fort Smith in 1887. The following year, the Sisters of Charity of Nazareth, a Roman Catholic order of nuns, opened Charity Hospital, now St. Vincent Infirmary in Little Rock. The Sisters of Mercy then established Saint Joseph’s Hospital—known as St. Joseph’s Mercy Health Center and then renamed Mercy Hot Springs in 2012—in Hot Springs. In 1892, Isaac Folsom of Lonoke (Lonoke County) made a bequest in his will to endow a free clinic bearing his name in Little Rock to be used for teaching. The widow of Colonel Logan H. Roots, furthering her husband’s dream of a city hospital, gave funds in 1895 to construct a city hospital on land purchased by the City of Little Rock. In 1896, the new hospital, under-funded and poorly equipped, opened its doors with seventy-five patient beds. In 1900, the Olivetan Benedictine sisters at Holy Angels Convent founded Saint Bernard’s Hospital, now St. Bernards Medical Center, in Jonesboro (Craighead County). Public support for improved standards of medical education and healthcare seemed to be building in Arkansas.

Corporate interests became involved as well. Railroads put doctors on retainer. The St. Louis and Iron Mountain Railroad (Missouri Pacific after 1917) opened an “emergency station” in 1917 in Little Rock and, in 1925, opened a large structure on Lincoln Avenue called the Missouri Pacific Employee Hospital Association Medical Facility. It became Riverview Medical Center in 1980 and closed in 1988.

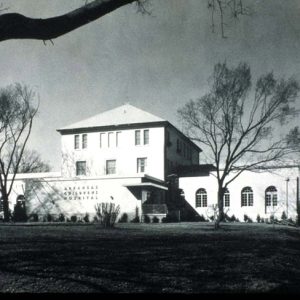

In 1912, the Arkansas Children’s Home opened as a facility for “orphaned, homeless and dependent children”; in 1926, the society established Arkansas Children’s Hospital in Little Rock.

Increasing professionalization of medicine led to the founding of the first medical school. The sponsors originally wanted to operate in conjunction with what turned out to be a failing institution, St. Johns’ College. Then they sought the imprimatur from Arkansas Industrial University, now the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County). The university trustees approved the charter on June 17, 1879. Dr. P. O. Hooper and seven associates incorporated this proprietary medical school, now the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS), which had no other official connection with the university whose name it used. By 1890, the first medical college boasted 113 matriculates. Divisions within the ranks led to a second school in 1906, the College of Physicians and Surgeons.

State institutions were created to deal with specific problems. Schools for the deaf and blind dated to 1850 and 1859, respectively, but a state mental health treatment center came much later. What is now the Arkansas State Hospital opened in 1883 as the Arkansas State Lunatic Asylum. Tuberculosis finally received state attention when the first sanatorium, for whites only, opened outside Booneville (Logan County) in 1910. Despite a greater incidence of tuberculosis among African Americans than whites, it was not until 1931 that a black sanatorium, subsequently named after Governor Thomas C. McRae, was established. One argument for its creation was that sick black servants would infect their white family charges. Dr. George W. S. Ish was instrumental in the institution’s founding, serving on its board from 1923 to 1967.

The Progressive Era inspired reforms. In 1901, the regular physicians cooperated with the other recognized schools to set up separate licensing boards. In 1909, the requirement of a diploma ended the apprenticeship system. The reform with the greatest long-term impact was a national survey of medical schools in the United States and Canada undertaken by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching under the auspices of the American Medical Association (AMA) and commonly named after the man who conducted it, Abraham Flexner. The only medical schools that Flexner thought deserved to survive were those affiliated with a university, those that had a teaching hospital, and those that taught science. Arkansas failed all counts, as was the case in much of the South.

In Arkansas, the Flexner Report forced the consolidation of the two schools, resulting in a UA takeover of the newly created school with separate legislative funding and eventually the building of a teaching hospital. In 1911, the state legislature agreed to assume fiscal responsibility for, and administrative control of, medical education in Arkansas. During the next year, new quarters for the consolidated school were established in the Old State House, with Dr. Morgan Smith as dean.

Meanwhile, the essential correlatives fell into place. The first nursing school had been started in 1895 in Fort Smith. By 1910, Arkansas had 354 trained nurses and 876 untrained ones. Training increased so that, in 1914, some fourteen hospitals in the state offered nursing courses. The Arkansas State Nurses’ Association organized in 1912, and, in 1913, the legislature set up a weak registration law that only prevented unqualified nurses from calling themselves “registered.” Almost all nurses were privately employed.

Public health took a giant leap forward when hookworms became the subject of a Rockefeller Sanitary Commission study. Hookworm infection in the state’s school children was very high. Dr. Smith, secretary to the Board of Health, managed not only the hookworm campaign but also the merger of the two medical schools. A vigorous apostle of public health, he got a bill creating a stronger board of health through both houses of the legislature, but opponents stole it. Smith blamed the National League for Medical Freedom, a patent-medicine-financed group that also included Christian Scientists and various “irregular” groups. Dr. Charles W. Garrison followed Smith and continued the hookworm campaign. In many rural counties where the problems were the greatest, the field physicians encountered open hostility. Garrison’s wife, Vinnie Middleton, used her talents in mobilizing the Arkansas Federation of Women’s Clubs, emphasizing the needs of children. A Health Train from Louisiana toured the state, loaded with exhibits. In 1913, the “lost” legislation was revived and became law. Act 96 of 1913 created vital statistics registration districts, but payment and hiring of registrars required remedial legislation in 1917 and 1923.

Work on eliminating mosquitoes followed. Dr. Zaphney Orto, then practicing at Walnut Ridge (Lawrence County) before moving to Pine Bluff, tried in 1882 to show a connection between malaria and mosquitoes. Dr. W. H. Deaderick of Marianna (Lee County) wrote A Practical Study of Malaria in 1909. A pilot federal program at Crossett (Ashley County) in 1916 stunned the world—between 1915 and 1916, there was a 72.23 percent reduction in malaria cases there. The U.S. surgeon general distributed nationwide a report of the experiment, “Public Health Bulletin No. 88,” that became the formula for sanitation workers around the world. The cleanup came at a cost of $1.26 per person, but Arkansas taxpayers were unwilling to fund such programs. Race played a role as well; Dr. W. H. Abington held that mosquitoes never bit black people.

Food and drug laws became important on the national scene. Arkansas had passed its first anti-adulteration law in 1893, but it was not until the early twentieth century that public attention became focused on the issues. The Hotel Inspection Act of 1917 required the State Board of Health to inspect hotels and restaurants as well as dairies, creameries, and schools, but without funds to hire an adequate number of inspectors, the law was largely ignored. Federal pure food and drug laws covered only interstate commerce, and prosecuted cases reveal that improperly canned or contaminated or mislabeled meats and vegetables did come out of Arkansas. Canners whose goods did not cross state lines were not inspected. Almost totally unregulated were patent medicines, despite the presence of alcohol and narcotics in their concoctions and their advertising claims to efficacy of the treatment.

One of the greatest challenges came with the influenza pandemic that reached Arkansas in 1918 and topped all twentieth-century killers. Federal officials at first minimized it by calling it “La Grippe,” a cold. But this viral infection hit hardest the seemingly most healthy young men and women. In a month, the state Board of Health put the entire state under quarantine because 1,800 cases had been reported in the first thirty days. At Camp Pike (now Camp Joseph T. Robinson) in North Little Rock (Pulaski County), where 52,000 soldiers were billeted, the men fell ill at the rate of 1,000 per day. Excluding the soldiers at Camp Pike, Arkansas reported 35,000 cases and 7,000 deaths. Although exact figures do not exist, approximately one of every four persons in central Arkansas contracted the disease. Some places escaped entirely. The tuberculosis sanatorium at Booneville quarantined itself immediately and escaped without a single case. The town, meanwhile, refused to act at all. Although the worst was over by November, the disease continued in and around the state for another year and spread to hogs.

Mid-Century Developments, 1920–1970

Medical education hoed a hard row for half a century. After the Arkansas Medical Department took up its new home in the Old State House, the legislature never appropriated enough money even to meet the minimum standards for accreditation by the American Medical Association’s Council on Medical Education. Enrollment in the rising freshman class fell to seven in 1919. The legislature refused to create the required charity hospital. A frustrated Dean Smith resigned in 1927. His replacement, Dr. Frank Vinsonhaler, fared no better. A 1931 federal survey called the institution a threat not just to Arkansas but to American health and called for its closure. Its Isaac Folsom Clinic bespoke “desolation, poverty and neglect,” while “makeshift” was the best that could be said of the Old State House site. Despite the facilities, Arkansas graduates found good jobs.

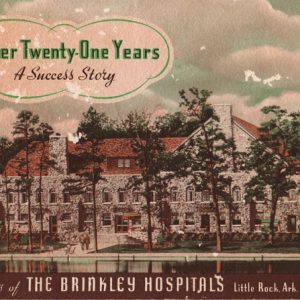

Arkansas’s climate of opinion hardly favored medical education. First, in 1928, voters banned the teaching of the theory of evolution from the state. Second, Arkansas became home to two of the most notorious quack physicians in America. John R. Brinkley, whose palatial hospitals were in Pulaski and Benton counties, attempted to save the sex lives of men by implanting goat gonads in them, while Norman Baker, ensconced in the Crescent Hotel and supported by the Eureka Springs Chamber of Commerce, purveyed false cancer treatments. Arkansas authorities looked the other way. Brinkley was brought down by civil suits; Baker fell afoul of federal authorities.

Meanwhile, medical professionals were uneasy with the new century. Most embraced the automobile, which allowed them to see more patients, and they often created hospitals in the state’s smaller towns so that patients could come to them. However, they took exception to Trinity Hospital’s prepayment plan. Founded in Little Rock in 1920, the hospital began to offer prepayment plans and group memberships. The Pulaski County Medical Society censured the participants, a move sustained by the state society. In 1946, Congress passed the Hospital Survey and Construction Act (Hill-Burton) that provided federal funds for hospital expansion.

Next, the AMA finally got revenge against the state’s public health officer, G. W. Garrison. Although an earlier generation of Arkansas doctors had created public health, nurturing and sustaining it against the opposition of the ignorant and patent medicine interests, the new leaders believed that public health, notably immunization, hurt them financially. County health nurses had done yeoman’s work during the Flood of 1927 and the Drought of 1930–1931, and were trying to raise the standards of midwives, but every immunized child was a patient lost. The newly elected governor in 1932, Junius Marion Futrell, was only too happy to replace the internationally recognized public health leader with a railroad physician, Dr. W. A. Grayson, whose main qualification was being from the governor’s home county.

Federal financial assistance, not any state commitment, kept programs partially alive during the Depression. Social Security, for instance, provided for maternal and children’s health, and public health nurses found plenty of work to do. In 1922, Fort Smith reported five cases of smallpox, while twenty-one persons died just west in Oklahoma. Outbreaks continued into the 1930s, although Arkansas’s requirement of vaccination for schoolchildren survived two judicial tests. The persistence of trachoma, a cause of blindness, had long been a disgrace. The diseased peaked in 1941, with 2,611 new cases. Prevention cost $4.80 per case and saved the state from paying the $120 per year allowance to the blind. Birth control came to Arkansas, both from private groups in Little Rock and from some county health units. Dr. Eva Dodge, a UAMS professor and obstetrical consultant to the State Health Department, worked with Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood.

The regulatory aspects of public health finally got attention in the 1930s. First, county health units finally were able to hire sanitarians, which the public called “privy inspectors.” Then, in 1939, the legislature authorized creating the Division of Food and Drug Control within the State Board of Health. When the agency finally began work in 1946, it concentrated on food, notably the shocking sanitary conditions prevailing in “shade-tree” canneries, eighty percent of which had no sanitary facilities for their workers. Tightened regulations reduced the number from more than 250 to 164. Federal regulators had more than 100 cases pending against Arkansas companies from interstate sales, but adoption of the new rules solved these problems. What was not solved was adulterated food—water added to tomatoes, for example. The division’s most challenging issue came in 1950 when the state’s canned spinach crop, normally nearly 3 million cases, was quarantined because of worm infestation. Between 1949 and 1954, the division brought criminal charges against 184 food processors, winning in all but five cases. The expenses of modernization drove most canneries out of business.

Milk inspections changed when the electrification of rural Arkansas made possible home refrigeration, electric milking machines, and other modern practices. Grade A pasteurized milk became the norm as private unpasteurized sales were banned. Virtually every sanitary improvement was in some way connected to the electric grid. Home septic tanks, for example, assumed the presence of an electrified well that supplied running water. Initially unregulated, septic tanks in low-lying areas failed to operate properly in wet weather, filling ditches with sewer water. Often builders constructed developments outside city limits in order to avoid having to pay for sewer connections. Improper septic tank installation threatened stream quality and contaminated wells. By 2001, both wells and septic tanks were subject to state regulation.

World War II furthered the war against malaria; Arkansas was one of twenty states given federal money to kill mosquitoes to keep military personnel healthy. The program was expanded in 1945 to cover nearby civilians. Widespread use of dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT) began after 1948 and led to a victory over malaria, though subsequent environmental problems led to its abandonment in the United States and spawned an environmental movement that took root even in Arkansas. Water quality was another issue addressed after World War II. The first “Water Supply Approved” signs went up outside seven Arkansas towns in 1953. Requirements included having a plumbing code and a licensed water operator.

One of the most controversial issues was midwifery. In 1940, Arkansas ranked third in the nation in deliveries attended by midwives, amounting to one-fourth of the state’s births. The state had three black board-certified obstetricians and a doctor shortage (one physician for every 1,382 persons). By 1945, even after federal assistance to the wives of service personnel, sixty percent of white women gave birth in hospitals, but only ten percent of black births occurred in hospitals. The maternal death rate for black women was two and a half times that of whites. The federal Sheppard-Towner Act had provided funds in the early 1920s. In 1945, a second midwife education campaign led by Mamie O. Hale also included granting state permits, and, by 1952, those working without a permit could be prosecuted. White doctors largely opposed midwives.

Crittenden Regional Hospital, then called Crittenden Memorial, was the first hospital in the state to be built with the aid of federal money from the Hill-Burton Act, treating whites and blacks since its completion in 1951. Local county societies excluded from membership the Delta’s few black doctors. Helena’s Dr. Robert D. Miller had to take his patients to Mound Bayou, Mississippi; others made covert arrangements for white doctors to get patients admitted. Changes came only after the passage of the Civil Rights Act (1964). A number of Delta hospitals were subsequently hit by lawsuits. Hill-Burton also required that hospitals accept a certain number of low-income/non-paying individuals, and later Medicare and Medicaid requirements were attached as well. Federal modernization forces doomed the old midwives, but the profession resurfaced in the 1970s.

By 1940, the medical school had become important enough to become a political pawn. Governor Homer Adkins organized the removal of the school’s new dean, Stuart P. Cromer, but problems remained under Cromer’s successor, Dr. Bryon Robinson, who, in 1942, refused to admit women. In 1943, negrophobe legislator W. H. Abington claimed the clinical facilities were only used by those from Pulaski County and that half of them were “Negro women having babies.” Some suggested that rural and small-town doctors were afraid of too much professionalism out of Little Rock.

After World War II, the medical center made great leaps forward. The first step was the admission of Edith Irby. The first African American to be admitted to a Southern medical school, she had to wait until racial liberal Sid McMath replaced segregationist Ben Laney as governor in 1949. The second step was the building of a modern medical center on West Markham in Little Rock. A $500,000 grant from the William Buchanan Foundation helped rally support, and, by 1955, the state at last had a modern teaching hospital and adequate classrooms. The school’s dean after 1950, Hayden Nicholson became a “super-salesman,” selling the institution to the state’s press and the AMA.

On October 5, 1951, ground was broken for University Hospital, the medical center of the University of Arkansas College of Medicine (now UAMS). Designed by Edward Stone, it was a nine-story, 450-bed facility with a seven-story educational building attached. Governor McMath and state Senator Ellis Fagan had introduced a cigarette tax to support the project; this eventually resulted in $6.4 million becoming available for the center. On June 18, 1956, the building was occupied by staff and patients. The center’s medical relevance was reinforced in 1976 when the Veterans Administration (VA) announced plans to move from Roosevelt Road to a site adjacent to the hospital.

Held together during the 1920s and early 1930s by its superintendent, Dr. Orlando P. Christian, Arkansas Children’s Home yearly teetered on the verse of collapse. A state-wide campaign in 1930 came just in time as more and more children, many suffering from malnutrition, came to the institution. An eleven-year-old boy suffering from pellagra and weighing just thirty-two pounds was one egregious case. Ruth Beall, a social worker from Benton County, took over in 1934. Financial problems continued, but home extension clubs sent their canned food (1,670 jars in 1941), and Beall got assistance from New Deal programs and a state law mandating county support. However, treating polio became a leading concern of the home since polio mostly affected children. The epidemic started in Arkansas in 1937 when 344 cases were reported. Numbers rose in 1946 to 408 cases and 992 in 1949. In 1950, the institution’s outpatient clinic was opened to African Americans, and, in 1955, it officially became the Arkansas Children’s Hospital. A one-mill Pulaski County tax gave it one steady source of income in 1978.

Helping children with severe disabilities was a special cause of Governor Orval Faubus, who finally got state money to create a model program, forty-seven other states having preceded Arkansas. First called the Arkansas Children’s Colony, it opened in Conway (Faulkner County) in 1959. Subsequent colonies were established at Arkadelphia (Clark County), in the old sanatorium at Booneville, and in Warren (Bradley County). These pioneering “non-institutional institutions” attracted nationwide attention and made the first Conway superintendent, David B. Ray, the leader in finding better ways of helping what heretofore had commonly been thought of as “idiots and imbeciles.” They were renamed “human development centers” in 1981.

The middle years of the century were full of other changes as well. Treatment for tuberculosis consisted in rest units (sanatoriums) away from other people. Leo E. Nyberg, a noted legislator from Phillips County, pushed successfully for more state aid in the late 1930s, making the Booneville sanatorium one of the best in the nation. However, in 1943, an antibiotic called streptomycin proved effective in destroying the tuberculosis bacilli in the human body. It took more than a decade for this discovery to make its way into therapies, and racism still permeated treatment. Dr. Paul Reagan, the director of the Division of Tuberculosis Control in 1961, called conditions at the McRae Sanatorium “appalling.” In 1960, the state expenditure per patient per day there was $2.82, compared to $8.66 at Booneville. Joycelyn Elders, later the surgeon general of the United States, volunteered along with others at McRae Memorial, physically examining patients. When McRae was closed by court order in 1966, its patients were to be transferred to Booneville, but that town’s remoteness from the state’s concentration of African Americans led Reagan to the then-controversial plan of using local hospitals and outpatient treatment. After that became the accepted method of treatment, the Booneville facility closed in 1973.

Changing medicine hit Hot Springs. While the belief died that drinking the water had medical benefits, the twentieth century’s polio outbreak created a new demand for hydrotherapy. After 1955, when the first polio vaccine appeared, the crisis atmosphere passed. Polio’s rapid decline was racially biased, however, since white children were much more likely to get immunizations. Smallpox inoculations stopped, but many other immunization programs followed. Betty Bumpers made immunization a major goal during the 1970s and continued campaigning in this field against inertia for more than thirty years.

The changing face of medicine meant that Arkansas Children’s Hospital had to refocus, adding occupational therapy, burn treatment, pediatric pharmacological research, clinical nutrition, eye care, and other specialties. The most publicized was the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). The burn center served adults as well, and helicopter service, represented in the state by Air Evac, superseded ground ambulances for urgent cases.

Another example of change could be found in treating venereal disease. Long a problem, syphilis in its tertiary stage resulted in mental collapse; infected females often suffered miscarriages, and the disease could be passed to children. At Hot Springs, a new Government Free Bath House opened in 1921. The Public Health Service established a treatment center for patients with venereal disease, the most common complaint of the poor who came for free thermal baths. In 1933, the federal government, as part of a nationwide program to house and feed indigent travelers, built a modern camp facility on the outskirts of Hot Springs. Of the 82,000 who applied for treatment at the center between 1921 and 1936, a total of 55,633 tested positive for venereal disease.

The World War II draft physicals revealed that ninety-three of every 1,000 Arkansans tested were infected, twice the national average; the black rate was nine times that of whites. The State Board of Health, which began creating clinics in 1937, now launched an extensive advertising and educational program during the war. Wartime dislocations sent the rates soaring, with Pine Bluff’s clinic treating 800 patients a week. Military bases were full of at-risk individuals, and federal programs tested prostitutes who worked the nearby towns. The state campaign continued after the war, with condoms for prevention and antibiotics for treatment. While syphilis declined, other sexually transmitted diseases, notably chlamydia and gonorrhea, took its place.

Continuing change was evidenced at the former insane asylum. The American Psychiatric Association’s diagnostic manual came into use in 1952. Early treatment consisted primarily of restraints; hydrotherapy was introduced in the 1930s, but a swimming pool was abandoned due to staff shortages. Photographs from the late 1920s show bedridden patients housed in the institution’s halls. A second unit was opened in 1936 at Benton to cope with the overcrowding. By 1956, the State Hospital had 5,086 patients, causing the legislature to replace the old building. The introduction of drug therapy made the new building obsolete almost as soon as it opened. A U.S. Supreme Court case on patients’ rights removed the senile to nursing homes. Decentralization followed, with fifteen regional health centers handling initial cases.

Finally, the relationship between doctor and patient changed in 1965 with the creation of Medicare. The debate over national medical care had been raging for decades, with President Harry Truman calling for a program in 1945. The AMA attacked “socialized medicine” as the worst threat doctors had ever encountered, but their repeated claim that no one in America had ever been denied medical care for financial reasons rang hollow, especially in Arkansas, particularly among African Americans.

Health in the Twenty-first Century

Late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century developments fall into two broad categories: public policy and disease history. Starting with the presidency of Ronald Reagan in 1980, Republican presidents were committed to privatizing Social Security and eliminating other New Deal–era programs. The adoption of Medicare/Medicaid led to an enormous increase in medical costs. Without direct market controls, the prices charged by doctors, hospitals, and pharmaceutical companies outran other inflation markers. Private insurance became increasingly expensive, and as unions lost ground, the plight of the uninsured became a major problem. States were forced to absorb and manage many of these programs. ARKids First, the state-run Medicaid program, covered some 77,000 children; its B plan provided lower-cost coverage for families with too much income to qualify for plan A.

A state campaign against tobacco use began in 2000 when Arkansas voters approved a comprehensive plan to use the state’s tobacco settlement funds for public health, medical education, and research. The Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids reported that twenty percent of Arkansas high school students smoked, compared to twenty-four percent of the general Arkansas population. In contrast to Arkansas’s usual poor rankings, the state ranked eighth in the nation on cessation spending.

Another problem surfaced in the 1990s as methamphetamines hit Arkansas. Arkansas ranked among the top states in usage. A state law restricting the sale of cold medications retarded local manufacture but not importations from Mexico. Violent crime, environmental damage, and abuse of children accompanied the drug’s use.

On the disease front, by the 1980s, tuberculosis cases in Arkansas dropped almost to zero, but in the twenty-first century, the disease has returned to the world in a more virulent strain known as multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis. Prisons in particular were at risk. Arkansas ranked twentieth among the states, and the foreign-born accounted for twenty-five percent of the total.

Environmental connections to diseases, especially cancer, became an issue in parts of the state since so many Arkansans relied on wells for water. Prairie Grove (Washington County) was the center for one “cancer cluster” that prompted state investigation. The Delta was particularly susceptible, since toxic dumps and other public health threats were often located in areas with large black populations.

The disease that attracted the most attention, HIV/AIDS, was first reported in Arkansas in 1983. From 1983 to 2003, 5,781 cases of HIV were reported. Of these, 3,558 turned into AIDS; forty-four percent of that number died by 2003. The disease was mostly found in urban settings, and Arkansas ranked thirty-second among the states in the number of cases. What made the disease particularly important in the Christian evangelical South was that it was spread primarily through sexual conduct. Christian leaders looked on it as God’s judgment on perverts, continuing to ignore any medical evidence to the contrary. Governor Mike Huckabee in 1992 declared that AIDS patients should be quarantined and opposed increasing funding research for this “gay disease,” comments that hurt him when he ran for president in 2008. Chris Beckham, an early sufferer from Camden (Ouachita County), founded the Arkansas AIDS Foundation in 1986 and campaigned tirelessly on behalf of victims.

Arkansas contributed to the problem of worldwide HIV and other diseases with its prisoner blood program. Begun in 1964 as a way for inmates to make money, the program actually enriched prison insiders. The plasma turned out to be contaminated with HIV and hepatitis C, leading to an international condemnation and a film documentary, Factor 8: The Arkansas Prison Blood Scandal.

Arkansas was affected by the U.S. Supreme Court’s abortion rights case Roe v. Wade (1973). This decision, more than any other, fueled one-issue politics (“I Vote Pro-Life”) that defined much of the state’s Republican Party. Since the states were left with regulatory powers during pregnancy’s last two trimesters, legislators threw every obstacle in the way of women obtaining abortions. Teen pregnancy remained a problem, but sex education based only on abstinence proved ineffective in addressing the problem.

Childhood obesity had doubled in two decades and tripled for adolescents. Arkansas ranked among the leading states in obesity in general. In 2003, 38.1 percent of Arkansas’s schoolchildren were either obese or at risk. A state law strongly supported by Governor Huckabee set in motion plans to remove soft-drink vending machines and other harmful food items from schools, and it instituted a yearly body mass index (BMI), the results of which would be mailed to parents. As a result, Arkansas became the only state to reverse the national trend, cutting the rate to 37.5 percent. However, led by Republican representative Kevin Anderson of Rogers, legislators modified the program in 2007, claiming that dealing with health issues was not a proper function of public schools.

On the other side of the age spectrum, the largest award ever granted by an Arkansas jury, $78 million, went to the family of Greta Sauer in 2001. This ninety-three-year-old woman died at Rich Mountain Nursing and Rehabilitation Center in Mena (Polk County) from dehydration, malnutrition, and Alzheimer’s. Congressman David Pryor had called attention to nursing home abuses in the 1970s, but problems continued, especially in the industry’s for-profit sector.

Recent developments show plainly a continuity with Arkansas’s past. Rural areas suffered from disparate Medicare reimbursements, causing small-town hospitals to close. In the bottom line–driven economy, insurance coverage vanished as jobs went overseas or never existed in the first place, as with adjunct employees in higher education and all other “independent contractors.”

However, some reprieve from a lack of health insurance was provided by the 2010 passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, commonly called the Affordable Care Act (ACA) or “Obamacare,” the latter after its main proponent, President Barack Obama. This act provided subsidies for uninsured people to help them obtain health insurance and eliminated the ability of insurance companies to use “pre-existing conditions” as an excuse for terminating benefits. States were allowed to set up their own health insurance exchanges, but many politically conservative states refused to do this. In Arkansas, Governor Mike Beebe, a Democrat, worked with a state legislature that was newly turned majority Republican to develop a compromise solution, and, in 2013, Arkansas became the first state in the United States to receive approval by the federal government to use Medicaid funds to establish the Health Care Independence Program (HCIP), popularly known as the “private option.” Under this system, the HCIP purchases private health insurance for eligible individuals whose income is up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. For the years 2014–2016, the program was 100 percent federally funded. This amount decreased each year after that period, with the state paying ten percent by 2021. This program made it possible for the state to modify a collection of Medicaid programs that provided benefits to the eligible population at seventy percent federal funding.

By January 2015, more than 250,000 Arkansas citizens who qualified for the private healthcare option had applied; counting Medicaid expansion, more than 300,000 Arkansans who had not been insured carried insurance. Hospitals and clinics saw a reduced rate of uncompensated care, leading to budget savings for state institutions. However, support for the private option decreased in the Arkansas legislature after the 2014 elections, with many of the legislators having opposed the program in their campaigns. Newly elected Republican governor Asa Hutchinson lobbied the legislature to fund the program as it currently stood through the end of 2016, resulting in Act 46 of 2015, which also established a task force to study the healthcare system and to suggest changes or revisions in 2017. However, the state legislature and the governor worked, in subsequent years, to limit the number of people on Medicaid, including instituting the nation’s first Medicaid work requirements, which, starting on June 5, 2018, required recipients to work or volunteer eighty hours a month, provided no exception was granted, or lose coverage and be unable to reapply until the following year. Healthcare groups complained that the work requirement would result in many losing their coverage and that the state’s online-only portal for reporting work hours was an onerous requirement in a state with poor Internet access. By the end of the year, more than 18,000 people had been removed from the Medicaid rolls due to the work requirement, but on March 27, 2019, a federal judge struck down work requirements in both Arkansas and Kentucky.

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) began sweeping the world beginning in late 2019. The virus created a large-scale public health crisis and cratered the economies of many nations throughout the world. The virus was first detected in Arkansas in March 2020. On February 15, 2023, Arkansas topped one million reported cases of COVID-19. By late March 2023, the Arkansas Department of Health had ceased to offer daily online updates on the disease and most considered the pandemic to be over, although cases were still seen.

Four years after the federal judge struck down the work requirements for Medicaid, hundreds of thousands of low-income Americans began losing Medicaid coverage as part of a far-reaching unwinding of a COVID-19–era policy that prohibited states from taking away the coverage. In Arkansas, more than 1.1 million people—over a third of its residents—were on Medicaid at the end of March 2023. In April, the first month that states could begin the removal process, about 73,000 people lost coverage, more than a third of them children seventeen and under. Some residents lost income because their income increased, but most were dropped due to procedural reasons, such as not turning in paperwork. Republican governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders argued that these measures were necessary to save money and allow Medicaid to stay within its intended scope. In an opinion essay in the Wall Street Journal in May 2023, she wrote, “We’re simply removing ineligible participants from the program to reserve resources for those who need them and follow the law,” adding that “some Democrats and activist reporters oppose Arkansas’s actions because they want to keep people dependent on the government.” Legislation passed in 2021 required Arkansas officials to complete the process in just six months, rather than the year that many other states were taking.

Medical education expanded in the twenty-first century. UAMS opened a campus in northwestern Arkansas in 2007. In the fall of 2016, Arkansas State University in Jonesboro opened the state’s first osteopathic medicine program in partnership with the New York Institute of Technology. A second osteopathic school, based in Fort Smith, opened in 2017.

Two powerful forces remain in Arkansas’s health climate. Professionally formatted plans invariably result in making political, economic, or religious enemies who often find the political process a useful tool to frustrate attaining some generally recognized good. A second force not as readily visible is inertia. In general, improvements have come from outside forces such as the federal government or sometimes even bureaucrats in Little Rock.

For additional information:

Abington, E. H. Back Roads and Bicarbonate: The Autobiography of an Arkansas County Doctor. New York: Vantage Press, 1955.

Arnold, Morris S. Colonial Arkansas, 1686–1804: A Social and Cultural History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

Bailey, Anne J., and Daniel E. Sutherland, eds. Civil War in Arkansas, Beyond Battles and Leaders. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Baird, W. David. Medical Education in Arkansas, 1879–1978. Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1979.

Baker, Max L., ed. Historical Perspectives: The College of Medicine at the Sesquicentennial. Little Rock: Arkansas Sesquicentennial Commission, 1986.

Bolton, Conevery A. “‘A Sister’s Consolation’: Women, Health, and Community in Early Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 50 (Autumn 1991): 271–291.

Bowen, Elliott. In Search of Sexual Health: Diagnosing and Treating Syphilis in Hot Springs, Arkansas, 1890–1940. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2020.

Brown, Pat Rhine. T. E. Rhine, M.D.: Recollections of an Arkansas Country Doctor. Little Rock: August House, 1985.

Carrigan, Jo Ann. “Nineteenth-Century Rural Self-Sufficiency.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 21 (Summer 1962): 132–145.

Dietrich, Fred W. The History of Dentistry in Arkansas: A Story of Progress. Camden, AR: Arkansas State Dental Association, 1957.

Finley, Randy. “In War’s Wake: Health Care and Arkansas Freedmen, 1863–1868.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 51 (Summer 1992): 135–163.

Floyd, Larry C., and Joseph H. Bates. Stalking the Great Killer: Arkansas’s Long War on Tuberculosis. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2023.

Hanley, Steven G. A Place of Care, Love and Hope: A History of Arkansas Children’s Hospital. 2nd ed. Little Rock: Arkansas Children’s Hospital, 2007.

Harris, Paul. “Formation of the Pulaski County Medical Society.” Pulaski County Historical Review 16 (March 1968): 1–9.

Henker, Fred O. “The Evolution of Mental Health Care in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 37 (Autumn 1978): 223–239.

Hosken, Simon Rosewall. “Conversations with West Memphis: A Sense of Place and Heritage.” PhD diss., Arkansas State University, 2011.

Hudgins, Mary D. “The Drumming Evil.” The Record 18 (1977): 89–96.

Jones, Creo A. Public Health in Montgomery County, Arkansas. N.p.: 1980.

Lancaster, Bob. “Malaria’s Mark.” Arkansas Times, January 1988, 34–37, 52–56.

Leveritt, Mara. “Bloody Awful.” Arkansas Times. August 16, 2007, pp. 12–14, 16. Online at https://arktimes.com/general/top-stories/2007/08/17/bloody-awful (accessed September 12, 2023).

Mann, Edwina Walls, ed. Contributions to Arkansas Medical History: History of Medicine Associates Research Awards Papers, 1988–1992. Kansas City, MO: Walsworth Printing Co., 1999.

Martin, Amelia W., ed. Physicians and Medicine in Crawford and Sebastian Counties, Arkansas, 1817–1976. N.p.: Sebastian County Medical Society, 1977.

Marvin, Horace N., ed. An Anthology of Arkansas Medicine. Fort Smith, AR: 1975.

Medicine in Arkansas Collection. Old State House Museum Online Collections. http://collections.oldstatehouse.com/collections/89/medicine-in-arkansas-collection;jsessionid=0D6E935A0B9F7C21252814978395A113/objects (accessed September 12, 2023).

Miller, Elissa L. “Arkansas Nurses, 1895–1920: A Profile.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 47 (Summer 1988): 154–170.

Moyers, David M. “From Quackery to Qualification: Arkansas Medical and Drug Legislation, 1881–1909.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 35 (Spring 1976): 3–26.

Nolan, Justin M., and Mary Jo Schneider. “Medical Tourism in the Backcountry: Alternative Health and Healing in the Arkansas Ozarks.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 35 (Winter 2011): 319–326.

Petersen, Svend. “Arkansas State Tuberculosis Sanitarium: The Nation’s Largest.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 5 (Winter 1946): 311–329.

Pitcock, Cynthia DeHaven, and Bill J. Gurley, eds. I Acted from Principle, the Civil War Diary of Dr. William M. McPheeters, Confederate Surgeon in the Trans-Mississippi. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2002.

Prewitt, Taylor. Before It Got Complicated: Medicine in Fort Smith and the Arkansas River Valley, 1817–1975. Fort Smith, AR: Red Engine Press, 2023.

Ross, Frances Mithell. “The New Woman as Club Woman and Social Activist in Turn of the Century Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 50 (Winter 1991): 317–351.

Scholle, Sarah Hudson. The Pain in Prevention: A History of Public Health in Arkansas. Little Rock: Arkansas Department of Health, 1990.

Shores, Elizabeth F. “The Arkansas Children’s Colony at Conway: A Springboard for Federal Policy on Special Education.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 57 (Winter 1998): 408–434.

Smith, C. Calvin. “Serving the Poorest of the Poor: Black Medical Practitioners in the Arkansas Delta, 1880–1960.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 57 (Autumn 1998): 287–308.

Taggart, Sam. Country Doctors of Arkansas. Little Rock: Arkansas Times, 2021.

———. The Public’s Health: A Narrative History of Health and Disease in Arkansas. Little Rock: Arkansas Times, 2014.

Valencius, Conevery Bolton. The Health of the Country: How American Settlers Understood Themselves and Their Land. New York: Basic Books, 2002.

Walls, Edwina, ed. Contributions to Arkansas Medical History: History of Medicine Associates Research Awards Papers, 1986–1987. Charlotte, NC: Delmar Printing Company, 1990.

Weiland, Noah. “Hundreds of Thousands Have Lost Medicaid Coverage Since Pandemic Protections Expired.” New York Times, May 26, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/26/us/politics/medicaid-coverage-pandemic-loss.html (accessed September 12, 2023).

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

ARKids First

ARKids First Adams, Elizabeth Lucille (Betty Lu) Hunter Sorensen

Adams, Elizabeth Lucille (Betty Lu) Hunter Sorensen Arkansas Country Doctor Museum (ACDM)

Arkansas Country Doctor Museum (ACDM) Arkansas Medical, Dental, and Pharmaceutical Association

Arkansas Medical, Dental, and Pharmaceutical Association Beauvoir College

Beauvoir College Bentley, Edwin

Bentley, Edwin Brooks, Ida Josephine

Brooks, Ida Josephine Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System

Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System Cestodes

Cestodes Civil War Medicine

Civil War Medicine Disease during the Civil War

Disease during the Civil War DuVal, Elias Rector

DuVal, Elias Rector Fort Logan H. Roots Military Post Historic District

Fort Logan H. Roots Military Post Historic District Garland, Mamie Odessa Hale

Garland, Mamie Odessa Hale Geophagy

Geophagy Harrison, William Floyd Nathaniel

Harrison, William Floyd Nathaniel Hot Springs Medical Journal

Hot Springs Medical Journal Human Dissection Monument

Human Dissection Monument Jones, Edith Irby

Jones, Edith Irby Jordan, Wilbert Cornelius

Jordan, Wilbert Cornelius Kaplan, Regina

Kaplan, Regina Kountz, Samuel Lee, Jr.

Kountz, Samuel Lee, Jr. Malaria Control Projects in Southeast Arkansas

Malaria Control Projects in Southeast Arkansas Medical Arts Building

Medical Arts Building Presbyterian Village

Presbyterian Village Rabies

Rabies Schoppach, Annie

Schoppach, Annie St. Vincent Hot Springs

St. Vincent Hot Springs Thomas C. McRae Memorial Sanatorium

Thomas C. McRae Memorial Sanatorium Welch, William Blackwell

Welch, William Blackwell Alexander George House

Alexander George House  Arkansas Children's Hospital

Arkansas Children's Hospital  Arkansas Children's Hospital

Arkansas Children's Hospital  Arkansas Children's Hospital

Arkansas Children's Hospital  Arkansas Children's Hospital

Arkansas Children's Hospital  Arkansas Children's Hospital Physical Therapy Equipment

Arkansas Children's Hospital Physical Therapy Equipment  Arkansas Country Doctor Museum

Arkansas Country Doctor Museum  Arkansas Pharmacist Association

Arkansas Pharmacist Association  Arkansas State Hospital

Arkansas State Hospital  Arkansas State Lunatic Asylum

Arkansas State Lunatic Asylum  Arkansas Tuberculosis Sanatorium

Arkansas Tuberculosis Sanatorium  Army-Navy Hospital Building

Army-Navy Hospital Building  Belle Point Hospital

Belle Point Hospital  Edwin Bentley

Edwin Bentley  Augustus L. Breysacher

Augustus L. Breysacher  Brinkley Hospital Brochure

Brinkley Hospital Brochure  John Brinkley

John Brinkley  Ida Joe Brooks

Ida Joe Brooks  Children's Drug Store Ad

Children's Drug Store Ad  Civil War Amputation Field Set

Civil War Amputation Field Set  Frank Coffin

Frank Coffin  Corn Hole Spring

Corn Hole Spring  Dermott Hospital

Dermott Hospital  Eva Dodge

Eva Dodge  Drug Treatment Center

Drug Treatment Center  Joycelyn Elders

Joycelyn Elders  Chastine Forbes

Chastine Forbes  Hale Bath House

Hale Bath House  Mamie Hale

Mamie Hale  Elisabeth Herndon

Elisabeth Herndon  Philo Hooper

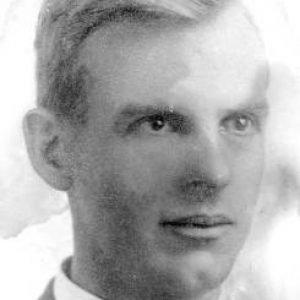

Philo Hooper  N. B. Houser

N. B. Houser  Human Dissection Monument

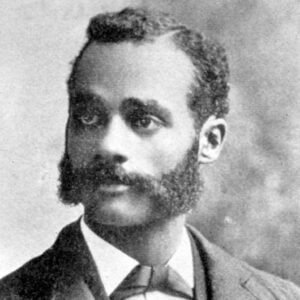

Human Dissection Monument  G. W. S. Ish

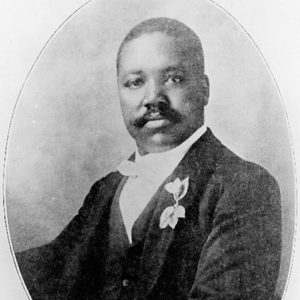

G. W. S. Ish  Roscoe Jennings

Roscoe Jennings  Jerome Relocation Center Hospital Crew

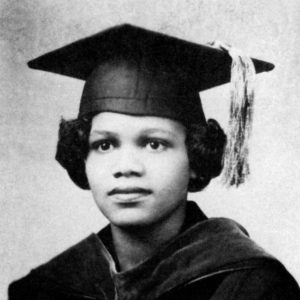

Jerome Relocation Center Hospital Crew  Edith Irby Jones

Edith Irby Jones  Lena Lowe Jordan

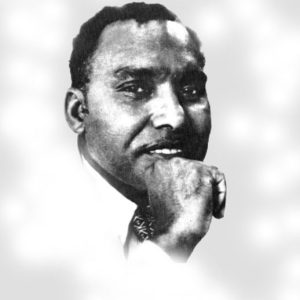

Lena Lowe Jordan  Samuel Kountz

Samuel Kountz  Little Rock Nurses

Little Rock Nurses  John McAlmont

John McAlmont  Midwives' Van

Midwives' Van  Missouri Pacific Hospital

Missouri Pacific Hospital  J. W. Morris

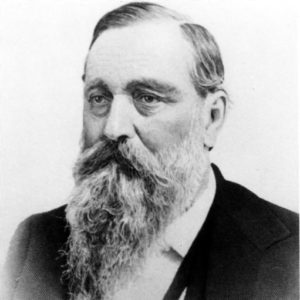

J. W. Morris  Dr. Charles E. Nash

Dr. Charles E. Nash  Zaphney Orto

Zaphney Orto  Paris Hospital

Paris Hospital  Parnell Springs Spring

Parnell Springs Spring  Tom Pinson

Tom Pinson  Margaret Pittman

Margaret Pittman  Prairie Grove Physicians

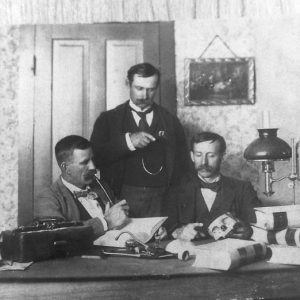

Prairie Grove Physicians  Annie Schoppach

Annie Schoppach  Betty Sorensen with Polio Patient

Betty Sorensen with Polio Patient  Sparks Regional Medical Center

Sparks Regional Medical Center  St. Bernards Medical Center

St. Bernards Medical Center  St. Bernards Medical Center Ticket

St. Bernards Medical Center Ticket  St. Bernards Medical Center

St. Bernards Medical Center  St. Vincent Infirmary

St. Vincent Infirmary  Henry Thibault

Henry Thibault  William Townsend

William Townsend  University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences  University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences  Frances L. Willoughby

Frances L. Willoughby  Wilson Clinic

Wilson Clinic

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.