calsfoundation@cals.org

Politics and Government

“Arkansas,” its leading newspaper once lamented, “has too much politics.” But while the state has seen plenty of noisy contention, healthy two-party competition has occurred only fitfully throughout its history. And the hoopla and hair-pulling of campaigns have typically been out of proportion to what state and local government actually did for—or required of—Arkansans.

Pre-European Exploration

Relatively little is known about how Arkansans were governed through the larger part of their past, there being no written records dating from before the era of European exploration. Archaeological evidence indicates that, by the Mississippian Period (AD 900–1600), the region harbored large settlements and intensive agriculture, its residents living in hierarchical societies governed by hereditary leaders exercising both political and religious authority. This authority sometimes extended beyond individual communities, but none of these chiefdoms seem ever to have united all of what would become Arkansas under a single government.

European Exploration and Settlement

European accounts give a clearer sense of how Native Americans governed themselves after the sixteenth century. Community life organized itself differently among various Indian groups. The Caddo lived in dispersed but hierarchical rural communities that allied with one another, forming confederacies. The Quapaw were also governed by hereditary chiefs and councils of male elders. But consensus as much as command seems to have structured Quapaw government, decisions for the tribe being made collectively by various town chiefs.

Indians supplied much of what government Arkansans enjoyed during that period, during which France and then Spain claimed the Mississippi River’s west bank. Theoretically, French and Spanish commandants at Arkansas Post enjoyed considerable political, military, and juridical authority. They presumed to regulate trade, commercial hunting, and Indian relations. But the settler population was too small, scattered, and obstreperous, and soldiers too few, for this power to be very meaningful. Moreover, the Quapaw and Osage refused to be governed by European law. The Quapaw had made themselves too essential to French survival—and the Osage were simply too powerful—for either to be bullied into submission.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

In the fifteen years after the Louisiana Purchase, Arkansas remained merely a district within a larger trans-Mississippi jurisdiction—dubbed Louisiana Territory in 1805 and renamed Missouri Territory in 1812—that comprised the whole of the purchase north of the thirty-third parallel. If anything, Arkansans complained that they were not governed enough under this arrangement. They could elect a delegate to Missouri’s legislature but, given their distance from the territorial capital of St. Louis, frequently had to do without basic public services. Important offices like judge and sheriff went vacant; court proceedings were erratic.

Services improved after Arkansas Territory came into existence in 1819. But until it had sufficient population to become a state, Arkansans enjoyed only limited opportunities for self-government. They could elect a territorial legislature, yet federal authorities appointed the territory’s governor and its top echelon of political and judicial officers, and Arkansas’s interests in Washington DC were represented by a single nonvoting member of the U.S. House of Representatives. If the federal government exercised the greater share of authority, it also paid many of Arkansas’s expenses, such as those incurred in building roads. The territorial period thus did little to lay the groundwork for government beyond whetting Arkansans’ appetites for federal largesse in preference to taxing themselves.

It also set enduring patterns in Arkansas politics.A loud, sometimes vicious factionalism emerged among politicians—one that typically centered less on policy or principle than personal reputation and the rewards of office. Robert Crittenden, Arkansas’s first territorial secretary, became the figure that other ambitious men rallied around or organized against. He gunned down the territory’s congressional delegate, Henry Conway, in a duel in 1827, highlighting the emergence of a rival faction that came to be known as “The Family” or “The Dynasty” and would include Conway’s surviving brothers, James and Elias Conway, their cousins Ambrose Sevier and Elias and Wharton Rector, and Sevier’s in-laws, Benjamin and Robert W. Johnson. Identifying themselves eventually with the Democratic Party, the Family held sway over Arkansas politics between statehood in 1836 and secession in 1861.

Nonetheless, the state never became a well-oiled political machine operated from the top down. By the standards of the day (which, of course, excluded women and nonwhites), the state possessed a broad electorate. The 1836 constitution placed no restrictions on adult white males’ right to vote. Citizens made the most of this, turnout in state elections being impressively high as compared to later eras. Accordingly, although state government was dominated by the elite, no politician could expect deference. Instead, campaigns were back-slapping, baby-kissing, whisky-drinking affairs. Moreover, the Family hardly ruled without challenge. Some prominent politicians—such as Archibald Yell, Chester Ashley, and Solon Borland—eventually put some distance between themselves and the Family, as did the state’s most important newspaper, the Arkansas Gazette. Family candidates increasingly faced opposition from other Democrats.

Interparty competition, though, was not so vigorous. The differing interests of the upland northwestern half of the state and the lowland southeast could be detected in the rivalry between Democrats and Whigs. While both parties garnered votes all over the state, the Whigs got a disproportionate share from slaveholding planters in the south and east and merchants and professional men in towns such as Little Rock (Pulaski County), Batesville (Independence County), and Van Buren (Crawford County). Whigs generally espoused the notion that it was government’s job to promote commerce and economic growth—by helping to build roads, canals, and railroads, and establishing banks to generate credit and capital. Democrats claimed they believed the public interest would be best served if government did relatively little, thus keeping taxes and public debt low—a stance bound to appeal to small farmers of the northern and western portions of the state, many of whom raised crops and livestock chiefly for their own consumption and for local exchange and rarely had much cash money to pay in taxes. Many more white yeomen than planters or businessmen lived in Arkansas, so Democratic presidential candidates consistentlycarried the state, and local Democrats won the important statewide elections and all but one congressional race in the antebellum years and always enjoyed healthy majorities in the state legislature. Still, class, regional, and policy divisions between the parties were far from stark. Democratic leaders were often slaveholding planters or otherwise tied to the lowland elite. More generally, politicians and officeholders, even in the uplands, tended to own slaves in greater proportions than the population at large. This gave southern and eastern Arkansas, and slaveholding interests generally, a purchase in politics far greater than might be suggested by Arkansas’s large nonslaveowning majority and the fact that representation in the state legislature was distributed according to white, rather than total, population (thus favoring the northwest).

From its inception, Arkansas government had to address what would remain its chief concerns in the twenty-first century: transportation, education, and economic development. The 1836 state constitution created comparatively vigorous executive and legislative branches, with governors serving four-year terms and legislators appointing the judiciary. Yet antebellum government achieved relatively little, leaving the state with neither a system of decent roads nor schools open to all willing children.

Regrettably, these failures highlighted what would prove to be enduring patterns in state government. The problem was not simply poverty, though many yeomen owned little taxable property.Rather, those most able to bear the expenses of government—in this era, slaveholding planters—saw to it that the lawmakers who answered to them kept their taxes low. Decentralization, furthermore, prevented the state from making the most of what resources it did have. Money raised for schools or roads, such as by selling public land donated by the federal government, was divided among localities, with the state doing little to ensure that effective use was made of it in cases of local indifference. The signal effort by which state government sought to accelerate economic growth—the bipartisan establishment in 1836 of the Arkansas State Bank and Real Estate Bank—fell victim not simply to a sour national economy but also to a phenomenon that would repeatedly mar the state’s developmental initiatives—prominent men’s eagerness to profit off of essential public work. Politically influential bank officials lent and borrowed recklessly, favored cronies, and earned hefty commissions. The banks’ failure left Arkansas with a multimillion-dollar debt that confounded state finance and politics for decades and prompted an early example of another recurring phenomenon in state government—the quick fix with enduring consequences. Disillusioned with banks generally, Arkansans amended their constitution in 1846 to forbid their establishment in the state, starving Arkansas of currency, credit, and capital.

Antebellum Arkansas government did one thing with skill, however: distribute land. The state parted with public land on generous terms. This is surely one of the reasons Arkansas attracted so many slaveholding settlers to its southeastern half in the 1850s, and these cotton-growing migrants reconfigured state politics. When politicians like Robert Johnson had first broached the idea of secession in 1850, they found many Arkansans decidedly unenthusiastic. But by the end of the 1850s, many more white Arkansans had reason to see their future as bound up with the future of slavery (though even then no more than one in five of them owned slaves). These newcomers, furthermore, had no built-in loyalty to the Family clique that had long dominated Arkansas. Accordingly, while the Whigs and a successor party, the Know-Nothings, disintegrated in the course of the 1850s, Family Democrats faced bigger trouble than they ever had before. Congressman Thomas Hindman, for instance, made hay out of the intense pro-slavery sentiments of the newcomers but also their lack of loyalty to the Family. In 1860, Henry Massie Rector turned his Family cousins out of power by being elected governor.

Civil War through Reconstruction

After Abraham Lincoln’s election, the geographical divide again surfaced in state politics, with majorities in northern and western Arkansas generally opposing immediate secession, while those supporting it were concentrated in the cotton regions of the south and east. But after Lincoln called up troops in April 1861, Arkansas quickly left the Union. Conservative former Whigs teamed up with old Family figures against Rector, but the fortunes of both factions were undone by warfare and emancipation. Government went to pieces. Mass enlistment, Union occupation, and guerrilla violence left the secessionist state government and local governments without the personnel or resources to carry out their duties. By early 1864, a second, Unionist state government had been established, but Federal troops did little to extend its authority beyond Little Rock.

The establishment of this loyal regime nevertheless represented a significant juncture in state politics and government. Longstanding Unionists, disillusioned secessionists, and loyal newcomers wrote a new state constitution in 1864. They officially abolished slavery but also tried more directly to reconstruct politics. They did not give former slaves the vote, but they did require voters to swear they had not voluntarily supported the Confederacy, thus disfranchising Arkansas’s Rebel elite. Shortly after the war ended in 1865, the Arkansas Supreme Court overturned these voting restrictions, and elections in 1866 packed the legislature with Democrats and erstwhile Whigs now united in the determination that Confederate defeat yield nothing more than the formal abolition of slavery. But a new order arrived all the same. Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts of 1867, requiring former Confederate states to write new constitutions that allowed black men to vote.

The Reconstruction Acts utterly changed who ran Arkansas and neatly reversed patterns set in antebellum politics and government. Instead of Democrats holding every significant office, Arkansas was governed by a newly hatched Republican Party supported by former slaves, many upland Unionists, and newcomers from the North called “carpetbaggers.” A very different electorate and class of officeholders emerged. Arkansas’s constitution of 1868 allowed black males to vote, while going farther than most other reconstructed states in preventing many old Confederates from voting. Many whites who technically could have qualified refused to swear the oath that required them to accept black equality. Probably a majority of Arkansans remained Democrats of some sort, but the party could not muster its full strength with these restrictions. African Americans never held office in proportion to their number in the population, yet they nevertheless exercised real power within a few years of slavery’s end, serving in the legislature and, in cities and Delta counties, occupying crucial local positions such as sheriff or alderman, as well as sitting on juries.

Reconstruction government also reversed antebellum precedent by making significant strides in education and transportation. Republicans hoped they could broaden their appeal beyond the black and white Unionist minority by fostering economic development. The Reconstruction legislature founded a genuine public education system, in the sense of establishing tax-supported schools in communities across the state. Another program rewarded railroad companies with state bonds for every mile of track constructed. Arkansas had only a few stunted lines going into Reconstruction but came out of it linked by rail to the nation and the world.

Yet these successes did not make Republicans more popular but instead convinced many white Arkansans that they were governed too much. Building a school system and subsidizing railroad construction cost a lot of money. Tax rates skyrocketed just as bad harvests and falling cotton prices made taxes harder to pay. As in other eras, essential public work, most notably the railroad program, was attended by profiteering, cronyism, graft, and ballooning debt. Governor Powell Clayton had used martial law and a bare-knuckled militia to stamp out racial and political violence, most notably that perpetrated by the hooded Democrats of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). That, combined with the obstacles many ex-Confederates faced in voting, allowed opponents to portray Reconstruction as undemocratic, though it had brought citizenship to the quarter of the state’s population that was African American.

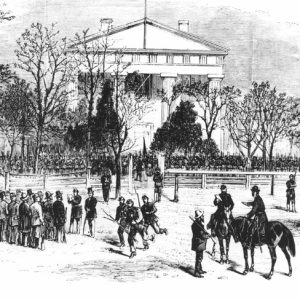

Republicans were their own worst enemies in another, more literal way. They divided over spending, corruption, and Clayton’s heavy-handedness. Scalawags resented the influence carpetbaggers wielded in the party. Republican infighting came to a confused climax with the Brooks-Baxter War of 1874. At some point during the stand-off, both Republican claimants to the governorship endorsed full restoration of voting rights to ex-Confederates, which almost certainly would put Democrats back into power. As Democrats began to vote at full strength, they indeed took the legislature and, by the end of 1874, the governorship.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

The Democrats’ revival did not make for healthy two-party politics as much as restore the lopsided hegemony of the antebellum era. Moreover, “Redeemer” Democrats’ quick fix to the “problem” of Reconstruction had enduring consequences. The constitution they wrote in 1874 remains in effect—though extensively amended—more than 130 years later. Democrats believed Reconstruction government had been too expensive and centralized. Accordingly, their constitution made the office of governor weaker. Most state officials (including the secretary of state and attorney general) and judges would no longer be appointed by the governor but instead elected. The 1874 constitution set governors’ terms at two rather than four years. Vetoes could be overridden by a simple majority. But the constitution also weakened the legislature, which thereafter met in regular session only once every two years. By the end of the twentieth century, governors were again serving four-year terms; legislatures were meeting frequently in special session. But Arkansas’s antiquated constitution still saddled the state with a comparatively weak executive and legislature.

In weakening the power of the governor and legislature, the constitution dispersed government authority to local hands. Officials elected at the county level—county judges, sheriffs, assessors, justices of the peace—had the most immediate influence over public life. For the next hundred years, an Arkansas county judge was, political scientist Diane Blair observed, “the closest thing to an uncrowned king that the American political system had to offer.”

The Democrats’ constitution clearly limited government’s ability to meet its responsibilities to education, transportation, and economic development. The constitution set maximum tax rates at low levels and restricted subsidization of railroads and other developmental initiatives. Since state and local government raised a good deal of its money through property taxes on rural real estate, Democrats’ retrenchment served the interests of the planters and landowning farmers who had long been the party’s core constituency. As in the antebellum era, the state did little to secure adequate revenue from those most able to bear the expense, and decentralization prevented the state from efficiently managing what resources it did have. Democrats destroyed the expensive and centrally administered educational system of Reconstruction, leaving much of the management and financing of schools in the hands of local districts, which numbered in the thousands by the 1880s and varied wildly in the resources they could apply to schooling. Democrats crippled even willing districts’ ability to support schools by sharply restricting local tax rates. Arkansas ended up spending a fraction of what many other states did on education.

However, if Democrats reshaped government and won all the big elections, the post-Reconstruction decades were not a period of political peace. Beyond a rudimentary consensus on lower taxes, smaller government, and white supremacy (which did not bar some Democrats from soliciting black votes), Democrats found plenty to disagree over, such as the state’s obligation to pay debts incurred by the antebellum banks and during Reconstruction. Ultimately, voters and the courts repudiated much of the debt. Arkansas’s reputation among investors, already badly tarnished, suffered all the more.

Besides internal divisions, other things kept Gilded Age Democrats’ power from being complete. Reconstruction’s expanded franchise was not immediately narrowed. About fifteen counties had black majorities; some others had large black minorities. For all the coercion and fraud Democrats might practice, many such places continued to produce large numbers of black votes. In some Delta communities, Democrats used their economic leverage to control black voters, such as by running uncooperative sharecroppers off their land. But in places where an effective Republican leadership survived, white Democrats had to share power or live under Republican rule. From the 1870s to the early 1890s, “fusion” prevailed in places like Crittenden, Jefferson, and Lee counties as Republicans and Democrats divvied up local offices. Black men thus continued to hold office in certain communities—and under the Arkansas constitution of 1874, local officials possessed considerable power. Dozens of African Americans also served in the state legislature in the twenty years after Reconstruction.

Other things created trouble for the Democrats by the 1880s. Many white farmers of modest circumstance, long a key element of the party’s constituency, were shifting their posture toward government as falling cotton prices mired them in debt or even forced them into tenancy. Some began demanding that the federal government circulate paper money and silver dollars to raise crop prices and lower interest rates, and that state government do more to regulate railroads and credit. By 1884, independent candidates had begun to challenge Democrats unwilling to embrace such demands. The threat that agrarian protest and continued black voting posed to Democratic supremacy became clear in 1888 with the gubernatorial campaign of the Union Labor Party, supported by members of the Agricultural Wheel, workingmen organized by the Knights of Labor, and many African Americans, as well as by white Republicans eager to topple Democrats by striking alliances with farm dissidents. Though a meaningful number of Democrats proved willing to meet farmers’ demandsto the extent of endorsing railroad regulation or the circulation of silver, ultimately, Democratic victories in 1888 and 1890 may well have hinged on the willingness of party members to employ fraud, coercion, and even violence against such opponents as John Clayton.

Democrats, however, hoped for a better fix both to the third-party challenge and African Americans’ lingering influence in local government. The Fifteenth Amendment prohibited denial of the right to vote on racial grounds, but election laws that Arkansas Democrats began to pass in 1891 disproportionately affected African Americans in making it more difficult for the poor and uneducated to vote. In a notable exception to their penchant for decentralization, Democrats provided that the state would appoint county election judges who, in turn, appointed precinct judges. With their control of state government, Democrats could thus ensure that even in counties where their opponents were numerous, Democrats might still run elections. This became vitally important because the same law mandated that ballots have no markings or symbols that might aid illiterates—only election judges could assist such voters in marking their ballot. Many chose not to vote at all rather than honor such arrangements, likely aiding passage in 1892 of a constitutional amendment requiring adult males to pay a poll tax before voting—a considerable burden for the many Arkansans, black and white, who were sharecroppers, tenant farmers, or hardscrabble landowners and rarely saw much cash. In the years that followed, Democrats limited the political participation of even those black voters who could pay a poll tax by straightforwardly banning them from voting in Democratic primaries—on the pretense that such elections were functions of a private organization and thus not subject to the Fifteenth Amendment. With opposition parties rendered noncompetitive by disfranchisement, Democratic “white primaries” became the elections that actually decided who held office. Such putatively legal efforts to render African Americans powerless went hand in hand with plainly extralegal devices—the forcible expulsion of black leaders, such as in Crittenden County, or of entire black populations, as in Harrison (Boone County), and rising numbers of lynchings.

Disfranchisement transformed Arkansas. The vigorous political participation that had distinguished the state since 1836 faded. After the mid-1890s, considerably less than half of adult males voted in gubernatorial elections. Indeed, it was another thirty years before as many people voted in Arkansas as had voted in 1890—and that was only after the electorate was doubled by women’s suffrage. Many poor Arkansans had their poll taxes paid and their political choices made by local bosses, but no longer would African Americans hold local office in the Delta. None were elected to the state legislature for another eighty years. Since black voters have typically by large majorities supported vigorous and generous government, disfranchisement almost certainly skewed Arkansas politics in a conservative direction.

With disfranchisement, Arkansas became a more thoroughly one-party state than ever before. There remained a residual Republicanism in several Ozark counties that had been citadels of Unionism during the Civil War and Reconstruction, but elsewhere the party found few supporters beyond aspirants to federal appointments. Instead, Democrats fought with other Democrats, though their factionalism seems in many cases not to have been the product of meaningful differences over policy or of popular enthusiasm for rival leaders, as much as representing transitory alliances among officeholders and politicos. This ultra-Democratic state, in fact, possessed an unusually weak state party organization. Some counties developed a species of machine politics, with bosses sculpting large majorities for favored candidates by creative ballot counting or the strategic deployment of poll tax receipts. Often, winning statewide or district elections was more a matter of arranging for a sufficient number of town or county grandees to deliver their votes, rather than candidates mobilizing their own loyal followings.

Oddly, though, at the same time political participation was being stifled, state government grew significantly more vigorous. The same legislature that initiated disfranchisement in 1891 passed a pioneering Jim Crow law, the Separate Coach Law, requiring segregated railroad coaches. By using law to manage a racial order that since emancipation had been propped up largely by informal means, Democrats anticipated Arkansans’ greater enthusiasm by the early twentieth century for using the powers of state to order economic and social life, a trend also exemplified by the prohibition movement.

Early Twentieth Century

This “progressive” impulse to regulate business more actively and attend to the public’s welfare had a number of sources. By the late 1890s, many Arkansas Democrats had embraced the rethinking of party doctrine associated most prominently with presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan, which looked to more positive action on the part of government to promote the well-being of the party’s target audiences of farmers and labor. Arkansas’s farmers and workers themselves, through groups like the Farmers’ Union and the United Mine Workers, pressed the state to act by regulating the cotton trade, limiting the work day, and ensuring safe working conditions. But the reform impulse also emerged out of the commercial and professional classes of Arkansas’s growing cities and towns. State agencies came to regulate railroads and utilities. Tentative efforts were made to have those most able to pay bear a larger portion of the tax burden. An inheritance tax passed in 1901 and a corporate franchise tax in 1907. The state restricted child labor, regulated the hours of women workers, and made a start on a welfare system, offering small pensions to needy mothers with dependent children. A new state board of health promoted safe food and water.

In addition to embracing new responsibilities, Arkansas government better served existing ones. After a new state highway commission was established, 2,500 miles of road were built during Governor Charles Brough’s term. Educational spending per student soared, and illiteracy fell. But the decentralization that had long hemmed in state initiatives continued to ensure that progress was decidedly uneven. By 1920, there were hundreds of highway districts and over 5,000 school districts in the state, each largely managing and financing its own extremely localized efforts, ensuring some Arkansans were far better served than others.

The movement to prohibit alcohol enlisted progressive reformers as well as religious conservatives. Most counties had already banned alcohol by 1916, when statewide prohibition on its manufacture and sale went into effect. The following year, the state banned importation. This fight against liquor advanced in tandem with a movement that reconfigured Arkansas’s electorate, many prohibitionists believing women’s suffrage would advance their cause. A 1917 law allowed Arkansas women to vote in party primaries. Since Democrats’ white primaries determined who won elections in one-party Arkansas, this gave white women real power even before women’s suffrage was enforced nationally in 1920.

Other reforms similarly placed more power in the hands of a citizenry simultaneously being diminished by the poll tax and the white primary. Arkansas’s initiative and referendum system, adopted in 1910, allowed citizens to pass laws or propose constitutional amendments by popular vote, rather than having to rely on a sometimes unresponsive legislature. Through it all, black citizens got less of what the state was doing more of, receiving a disproportionately small amount of what the state spent on citizens’ welfare.

Arkansas participated in the more conservative national mood of the 1920s. As was the case elsewhere, a new Ku Klux Klan briefly became important in state politics. In 1928, Arkansans used the initiative procedure to ban the teaching of evolution in public schools. Yet Arkansas government in the 1920s continued along its expansive trajectory, expressing what some have termed a “business progressivism,” as much oriented toward economic growth as social justice. Arkansas lawmakers in the 1920s spent more on education and, especially, transportation; in doing so, they started to reshape a tax system still heavily reliant on property taxes though many landowners were poor. The state began to levy taxes (albeit modest) on incomes and natural resources extracted in Arkansas, as well as on cigarettes and gasoline. However, as with earlier state initiatives, highway building saddled the state with a huge debt deepened by cronyism and corruption.

The crisis of the Great Depression required quick and enormous fixes that had their own enduring consequences for how Arkansans were governed. Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal made for a far more immediate governmental presence in Arkansans’ daily lives. The Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) inaugurated a federal system of subsidies that remained central to Arkansas farming long after the Depression ended, while also encouraging many landowners to rid themselves of sharecroppers and tenants and switch to day labor. Social Security significantly expanded upon Arkansas’s meager welfare system. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) built thousands of miles of roads and hundreds of public buildings in the state. The Rural Electrification Administration (REA) promoted dramatic changes in how Arkansans lived and worked. One reason that Arkansas could get a healthy share of New Deal spending was that U.S. Senator Joseph T. Robinson was Senate majority leader and a crucial ally of Roosevelt.

Arkansas’s own fixes for its Depression-era problems had similarly enduring consequences for state government spending and the burdens it placed on citizens. With the state unable to pay its huge debt or collect taxes from impoverished citizens, Arkansans amended their constitution in 1934 to hem in future spending. The amendments made it more difficult for the state to issue bonds and required a nearly impossible three-fourths vote of the legislature, or a popular vote, to increase state taxes then in effect—most notably income and property taxes. The sales tax, instituted the following year, did not fall under this requirement. Thereafter, when the state needed more revenue, it most often hiked sales taxes. By the late twentieth century, the state’s (and localities’) fondness for the sales tax, together with an income tax that enforced the same rates for billionaires and those with modest incomes, left Arkansas with a decidedly regressive tax system that placed a disproportionate burden on poorer citizens.

World War II through the Faubus Era

After World War II, state government continued to dwell on its perennial concerns. Efforts to promote economic development now centered on an ongoing campaign to lure out-of-state industry to Arkansas. Arkansans increased the tax revenue that could be directed to schools, and they voted in 1948 to reduce the state’s huge number of school districts significantly, so that each was big enough to support a high school. Under Governor Sid McMath, Arkansas built more roads than under any earlier governor—though charges surfaced that, once again, essential public work had been marred by corruption and political backscratching.

The postwar era also saw a comprehensive reordering of the personnel of Arkansas politics and attendant shifts in the constituencies, principles, and relative strength of the Democratic and Republican parties. A new generation of political leaders emerged in the 1940s. Young veterans like McMath, determined to make their mark in politics, began challenging entrenched local political machines, creating what would be labeled the GI Revolt. But things more fundamental undermined those machines. Increasingly, Arkansas politics was conducted on a statewide basis rather than being a ramshackle accumulation of influence exercised locally and voters mobilized locally. As the twentieth century proceeded, corporations such as Arkansas Power and Light (AP&L), Arkansas Louisiana Gas Company, and Stephens, Inc., being regulated by or doing business with state government, cultivated a broader influence, courting legislators and governors. With the spread of radio and then television, campaigning was increasingly conducted via mass media, rather than by button-holing voters. By the 1970s, the significance of local government diminished somewhat as federal and state funds accounted for a larger share of public spending.

Important shifts were occurring among the electorate as well. Hundreds of thousands of Arkansans left the state during the Depression, World War II, and postwar decades to pursue greater opportunity elsewhere. Accordingly, Arkansas’s representation in the U.S. House of Representatives dropped from a high of seven seats (1902–1950) to only four by the 1960s. Migration, which flowed chiefly from rural areas, also shifted power within the state. The U.S. Supreme Court required in 1964 that state legislative districts be drawn in such a way as to accord each community representation in proportion to its population, diminishing rural counties’ influence in state government and increasing that of growing cities and suburbs.

In the meantime, the postwar renaissance of black politics reconstituted the electorate and realigned the parties. With the New Deal, the Democratic Party nationally had more straightforwardly embraced energetic and expansive government and organized labor and, by the late 1940s, began to endorse its growing black constituency’s demands for civil rights. This created a distinct tension between the national organization and the Democratic Party of Arkansas, which included many members who hewed to the old doctrines of states’ rights and small government, as well as others who welcomed a federal government generous enough to build dams, promote rural electrification, and subsidize agriculture but not one that promoted black equality or union representation. At the same time, black Arkansans by 1950 had secured court decisions guaranteeing their right to run and vote in Democratic primaries. Some white moderates, such as McMath, proved willing to accommodate this growing electorate by making room for them in the party and on state boards and commissions. But in Arkansas, as in much of the South, grassroots pressure against federal mandates for desegregation resulted in a powerful politics of “massive resistance.” Governor Orval Faubus most conspicuously reaped the rewards of the massive resistance, being reelected repeatedly after his flagrant obstruction of the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School in 1957—though his popularity surely also had to do with his administration’s more constructive legacy, such as increased funding for education and improved care for the mentally handicapped.

Modern Era

Yet massive resistance could not preserve the political status quo. The work of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Voter Education Project helped ensure that about half of eligible black voters had been registered by 1964. The poll tax had been the chief instrument of disfranchisement (as well as election fraud), but by 1964, an amended U.S. Constitution banned it as a prerequisite for voting in federal elections, and Arkansas surrendered its use in state elections. With African Americans voting freely in far greater number, officeholding was transformed. By the 1970s, black legislators were being elected from urban counties like Pulaski and Jefferson. It would require further federal legislation, notably a new voting rights act in 1982, and a 1989 court decision before black officeholding returned to the Delta in a meaningful way.

Party competition was necessarily transformed. African Americans proved willing to vote for Democratic presidential candidates who embraced civil rights and anti-poverty programs, but they initially proved more tentative about Arkansas Democrats, given the state organization’s bleak record on race. Many white moderates had decided by the mid-1960s that civil rights was a trend that had to be accommodated and that it would be to Democrats’ advantage to secure those growing numbers of black voters. But white conservatives remained bent on retaining a hold on the state’s Democratic Party, though in many respects they were more ideologically in tune with Republicans who, by 1964, had become, at the national level, the party less friendly to expensive and intrusive government. Enough of these conservative Democrats remained that the gubernatorial nomination in 1966 went to the central architect of massive resistance, Jim Johnson. His opponent, Winthrop Rockefeller, on the other hand, embraced a liberal Republicanism more comfortable with the idea of civil rights and generous government. As a result, many moderate Democrats and some ninety percent of black voters backed Rockefeller. Arkansas thus had its first Republican governor (as well as its first Republican congressman, John Paul Hammerschmidt) since Reconstruction. But political realignment initially went no deeper than that. Arkansas was considerably slower than other Southern states to vote for a Republican presidential candidate, and Rockefeller faced a legislature still overwhelmingly Democratic.

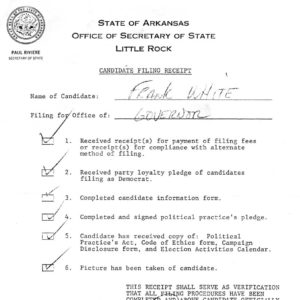

While Arkansas in 1966 saw real party competition for the first time since the squelching of the Union Labor Party, the two parties had not yet assumed their contemporary forms. Things began to sort themselves out by 1970. After another contentious primary, Democrats nominated a moderate, Dale Bumpers, for governor, bringing back progressive whites who had voted for Rockefeller. Bumpers, like Faubus, embraced generous government but, unlike Faubus, shunned segregationism, a combination that won him more black support. The Democratic governors who immediately succeeded Bumpers—David Pryor and Bill Clinton—were also in the moderate rather than the Faubus mold. This new generation of Democratic moderates got most of the black vote and got along reasonably well with Democrats in Washington DC. For their part, Republicans took another path after Rockefeller lost in 1970. The next Republican governor, Frank White, elected in 1980, was not a liberal Rockefeller Republican but instead a former Democrat who found that party no longer sufficiently conservative. This was increasingly the source of Republican strength in Arkansas—people who continued to believe in states’ rights, small government, low taxes, and social conservatism but now found the GOP to be the better standard bearer for those values. Though Arkansas Democrats often positioned themselves to the right of Democrats elsewhere on “social” issues such as gun control, abortion, and gay rights, a fundamental political realignment had occurred by the late twentieth century, with black voters now a central element in the Democratic coalition, while many conservative whites voted Republican.

Republicans gained ground not just because they had become the spokesmen for the low-tax, morally conservative philosophy that many Arkansans had long favored, but because by the 1990s, the party was especially strong in the most rapidly growing regions—the spreading suburbs of Little Rock and northwest Arkansas. By 2000, Arkansas had a well-liked Republican governor, had sent a Republican to the U.S. Senate for the first time since Reconstruction, saw the number of Republicans in its legislature multiply several times over since 1980, and was routinely voting Republican in presidential elections, except when Clinton was on the ticket. Still, Arkansas, for a Southern state, continued to sport a congressional delegation, legislature, and local governments top-heavy with Democrats, at least until the 2010 election, when Republicans saw big gains at all levels. But it was only in 2012 that Arkansas really caught up with the rest of the South in the extent of its Republicanization, with the GOP capturing a majority in the Arkansas General Assembly for the first time since Reconstruction, as well as sweeping the state’s four spots in the U.S. House of Representatives and both U.S. Senate seats. The political flux of the early twenty-first century, however, was the product not just of see-saw party competition but of an unusually rigorous term-limits measure imposed in the 1990s. It ultimately sent even the most popular and talented legislators packing after several terms (three two-year terms for House members and two four-year terms for senators), likely contributing to governors’ increased influence over budget and policy making.

Governor Mike Huckabee, who served more than ten years, embodied (in wildly varying shapes) the changes the state had seen in party politics, but his career also suggested certain continuities in Arkansas government in that he embraced the business progressivism of a number of his predecessors, justifying more generous government initiatives in education, transportation, and healthcare in the name of economic development as much as social well-being. Indeed, Huckabee seemed to follow carefully what political scientist Jay Barth has identified as the prescription for political success in Arkansas—promoting government services that might aid Arkansans’ material circumstances while hewing to a noisy conservatism on “social” issues. Arkansas government under Clinton and Huckabee made admirable strides in meeting its longstanding responsibilities: distinct enhancements in educational funding and quality, better healthcare (particularly for children), and an improved road system. But though portions of the state were booming, Arkansas remained in the twenty-first century a comparatively poor, unhealthy, and poorly educated state. Certainly, government alone was not responsible for this situation, but as late as 2002, courts were taking the state to task for a school system whose inadequacy and inequity had plain roots in the decentralization enforced by Democrats in the 1870s, showing how Arkansas remained hobbled by its politicians’ history of quick fixes.

For additional information:

Arnold, Morris. Unequal Laws unto a Savage Race: European Legal Traditions in Arkansas, 1686–1836. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1985.

Arsenault, Raymond. The Wild Ass of the Ozarks: Jeff Davis and the Social Bases of Southern Politics. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1984.

Barnes, Kenneth C. The Ku Klux Klan in 1920s Arkansas: How Protestant White Nationalism Came to Rule a State. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2021.

———. Who Killed John Clayton? Political Violence and the Emergence of the New South, 1861–1893. Durham: Duke University Press, 1998.

Barth, Jay, and Janine A. Parry. “Arkansas: Trump Is a Natural for the Natural State.” In The Future Ain’t What It Used to Be: The 2016 Presidential Election in the South, edited by Branwell Dubose Kapeluck and Scott E. Buchanan. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018.

Blair, Diane, and Jay Barth. Arkansas Politics and Government. 2nd ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Bolton, S. Charles. Arkansas, 1800–1860: Remote and Restless. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1998.

Branam, Chris W. “‘The African Have Taken Arkansas’: Political Activities of African Americans in the Reconstruction Legislature.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 73 (Autumn 2014): 233–267.

Boyett, Gene. “Quantitative Differences between the Arkansas Whig and Democratic Parties, 1836–1850.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 34 (Autumn 1975): 214–226.

Brown, Walter L. A Life of Albert Pike. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Clinton, Bill. My Life. New York: Knopf, 2004.

Davis, John C. From Blue to Red: The Rise of the GOP in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2024.

Davis, John C., Andrew J. Dowdle, and Joseph G. Giammo. “Arkansas: Should We Color the State Red with a Permanent Marker?” In The New Politics of the Old South: An Introduction to Southern Politics, 7th ed., edited by Charles S. Bullock III and Mark J. Rozell. Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield, 2022.

DeBlack, Thomas. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Donovan, Timothy, Willard Gatewood, and Jeannie Whayne, eds. The Governors of Arkansas: Essays in Political Biography. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Dumas, Ernie. The Education of Ernie Dumas: Chronicles of the Arkansas Political Mind. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2019.

Glaze, Tom, with Ernie Dumas. Waiting for the Cemetery Vote: The Fight to Stop Election Fraud in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2011.

Graves, John. “Negro Disfranchisement in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 26 (Autumn 1967): 199–225.

Hill, Kennedy Lynn. “Representative Government: An Evaluation of Single-Party Dominance in the State of Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2022. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/4425/ (accessed December 1, 2023).

Hoffman, Kim U., Janine A. Parry, and Catherine C. Reese. Readings in Arkansas Politics and Government. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Johnson, Ben F. Arkansas in Modern America since 1930. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

———. John Barleycorn Must Die: The War Against Drink in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2005.

Key, V. O. Southern Politics in State and Nation. New York: Knopf, 1949.

Ledbetter, Calvin, Jr. “Arkansas Amendment for Voter Registration without Poll Tax Payment.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 54 (Summer 1995): 134–162.

———. Carpenter from Conway: George Washington Donaghey as Governor of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

McMath, Sidney S. Promises Kept: A Memoir. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Moneyhon, Carl. Arkansas and the New South, 1874–1929. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

———. “Black Politics in Arkansas during the Gilded Age, 1876–1900.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 44 (Autumn 1985): 222–245.

———. The Impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction on Arkansas: Persistence in the Midst of Ruin. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994.

Niswonger, Richard. Arkansas Democratic Politics, 1896–1920. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

Parry, Janine A., and Jay Barth. “Arkansas: Another Anti-Obama Aftershock.” In Second Verse, Same as the First: The 2012 Presidential Election in the South. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2014.

Parry, Janine A., and Dusty Higgins. “Arkansas’s Cartoon Campaign Advertisements, 1942–1970.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 77 (Autumn 2018): 208–249.

Parry, Janine A., and William H. Miller. “‘The Great Negro State of the County?’ Black Legislators in Arkansas, 1973–2000.” Journal of Black Studies 36 (July 2006): 833–872.

Perkins, J. Blake. “Dynamics of Defiance: Government Power and Rural Resistance in the Arkansas Ozarks.” PhD diss., West Virginia University, 2014.

Pierce, Michael. “How to Win a Seat in the U.S. Senate: Carl Bailey to Bill Fulbright, October 20, 1943.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 76 (Winter 2017): 334–361.

Pruden, William H., III. “Holding the Line: The Arkansas Congressional Delegation and the Fight over a Federal Antilynching Law.” In Bullets and Fire: Lynching and Authority in Arkansas, 1840–1950, edited by Guy Lancaster. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2018.

———. “Politics, Partisanship, and Peace: The Arkansas Congressional Delegation and World War I.” In To Can the Kaiser: Arkansas and the Great War, edited by Michael D. Polston and Guy Lancaster. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2015.

Reed, Roy. Faubus: The Life and Times of an American Prodigal. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Smith, Lindsey Armstrong, and Stephen A. Smith. Stateswomen: A Centennial History of Arkansas Women Legislators, 1922–2022. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2022.

Urwin, Cathy Kunzinger. Agenda for Reform: Winthrop Rockefeller as Governor of Arkansas, 1967–71. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

Walton, Brian. “How Many Voted in Arkansas Elections before the Civil War?” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 39 (Spring 1980): 66–75.

———. “The Second Party System in Arkansas, 1836–1848.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 28 (Summer 1969): 120–155.

White, Lonnie. Politics on the Southwestern Frontier: Arkansas Territory, 1819–1836. Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1964.

Woods, James. Rebellion and Realignment: Arkansas’s Road to Secession. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1987.

Woods, Randall. Fulbright: A Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Patrick G. Williams

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Adkins, Homer Martin

Adkins, Homer Martin Agricultural Adjustment Act

Agricultural Adjustment Act Alexander, Henry McMillan

Alexander, Henry McMillan Arkansas Council of Defense

Arkansas Council of Defense Arkansas Libertarian Party

Arkansas Libertarian Party Arkansas Plan

Arkansas Plan Beebe, Mike

Beebe, Mike Boodle Prosecutions

Boodle Prosecutions Boozman, John

Boozman, John Breckinridge, Clifton Rodes

Breckinridge, Clifton Rodes Constitutional Conventions

Constitutional Conventions Davis, Jeff

Davis, Jeff Dueling

Dueling Equal Rights Amendment (ERA)

Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) Farkleberry Follies

Farkleberry Follies Featherstone v. Cate

Featherstone v. Cate Grand Gulf Affair

Grand Gulf Affair Greenwood, Alfred Burton

Greenwood, Alfred Burton Hadley, Ozro Amander

Hadley, Ozro Amander Hartman, Alexis Karl

Hartman, Alexis Karl Populist Movement

Populist Movement Revenue Stabilization Act

Revenue Stabilization Act Rhoton, Lewis Nathan

Rhoton, Lewis Nathan Searcy, Richard

Searcy, Richard Socialist Party

Socialist Party Webb, Doyle

Webb, Doyle Homer Adkins with FDR

Homer Adkins with FDR  Homer Adkins

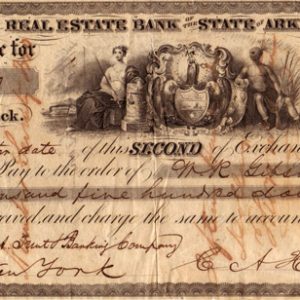

Homer Adkins  Arkansas Real Estate Bank Draft

Arkansas Real Estate Bank Draft  Arkansas State Seal

Arkansas State Seal  Carl Bailey Sticker

Carl Bailey Sticker  Battle of Palarm

Battle of Palarm  Brooks-Baxter War

Brooks-Baxter War  Charles Brough at Elaine

Charles Brough at Elaine  Bumpers, Bumpers, Parker, and Ferguson

Bumpers, Bumpers, Parker, and Ferguson  Dale Bumpers Inauguration

Dale Bumpers Inauguration  Ben Butler with Orval Faubus

Ben Butler with Orval Faubus  Hattie and Thaddeus Caraway

Hattie and Thaddeus Caraway  Hattie Caraway Appointment Certificate

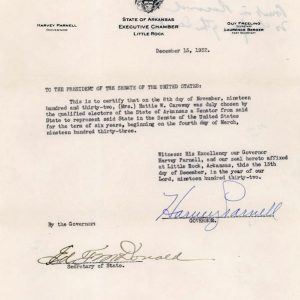

Hattie Caraway Appointment Certificate  Centennial Celebration

Centennial Celebration  Francis Cherry

Francis Cherry  Francis Cherry

Francis Cherry  Francis Cherry Campaign Postcard

Francis Cherry Campaign Postcard  Hillary Clinton

Hillary Clinton  Jeff Davis

Jeff Davis  Donaghey Mock Funeral

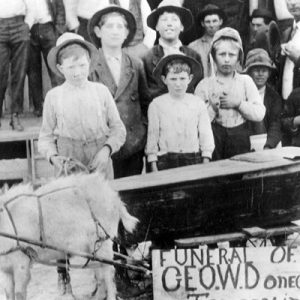

Donaghey Mock Funeral  James Eagle Campaign Arch

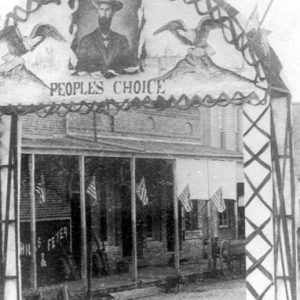

James Eagle Campaign Arch  Dwight Eisenhower's Diary

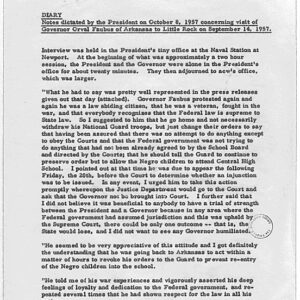

Dwight Eisenhower's Diary  Faubus Campaign Brochure

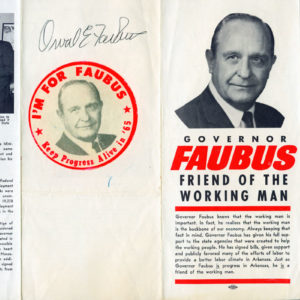

Faubus Campaign Brochure  Five Arkansas Governors

Five Arkansas Governors  John Paul Hammerschmidt

John Paul Hammerschmidt  Janet Huckabee

Janet Huckabee  Asa Hutchinson at CSA Arrest

Asa Hutchinson at CSA Arrest  Hutchinson, Hutchinson, and White

Hutchinson, Hutchinson, and White  Jerome Relocation Center

Jerome Relocation Center  Virginia and Jim Johnson

Virginia and Jim Johnson  Ben Laney with Congressional Delegation

Ben Laney with Congressional Delegation  Benjamin Laney

Benjamin Laney  John McClellan

John McClellan  Sid McMath with Truman

Sid McMath with Truman  Wilbur Mills Brochure

Wilbur Mills Brochure  Official State Flag

Official State Flag  Old Guard Home Parody

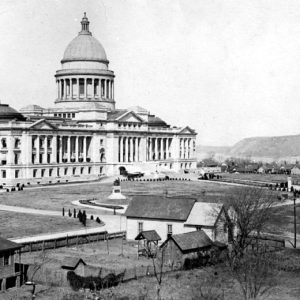

Old Guard Home Parody  Old State House

Old State House  Old State House

Old State House  Old State House

Old State House  Old State House, Union Occupation

Old State House, Union Occupation  Ozark Frontier Trail Festival

Ozark Frontier Trail Festival  Quapaw Treaty of 1824

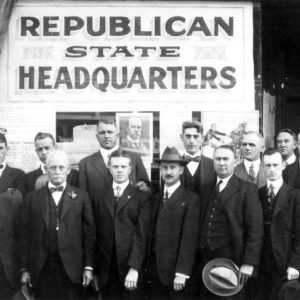

Quapaw Treaty of 1824  Republican Party Leaders

Republican Party Leaders  Joseph J. Reynolds

Joseph J. Reynolds  Joe T. Robinson

Joe T. Robinson  Joseph Taylor Robinson House

Joseph Taylor Robinson House  Winthrop Rockefeller on Victory Train

Winthrop Rockefeller on Victory Train  Winthrop Rockefeller Campaign Sticker

Winthrop Rockefeller Campaign Sticker  Sesquicentennial Seal

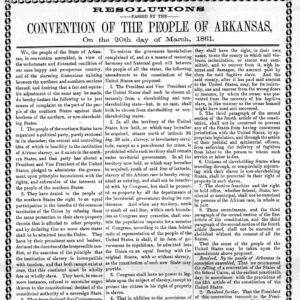

Sesquicentennial Seal  Slavery Resolution

Slavery Resolution  Betty Sorensen

Betty Sorensen  State Capitol Building

State Capitol Building  George Bush with Gay and Frank White

George Bush with Gay and Frank White  Frank White's Gubernatorial Candidate Form

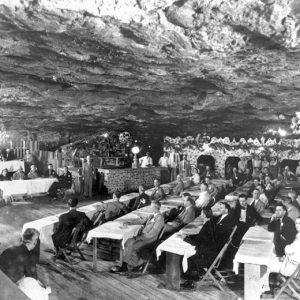

Frank White's Gubernatorial Candidate Form  Wonderland Cave

Wonderland Cave

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.