calsfoundation@cals.org

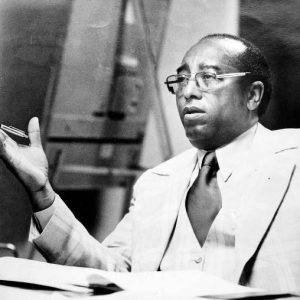

Charles E. Bussey Jr. (1918–1996)

Charles E. Bussey Jr. was the first African American elected to serve on the Little Rock (Pulaski County) City Board of Directors since Reconstruction, the first African-American deputy sheriff of Pulaski County, and the first African-American mayor of Little Rock. Charles Bussey Avenue in Little Rock was named for him in 2005, and he was posthumously inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame in 2006.

Charles Bussey—often called Charlie—was born in Stamps (Lafayette County) on December 18, 1918, the eldest child of Annie Bussey and Charles Bussey Sr. Acclaimed author Maya Angelou, who also grew up in Stamps, recalled that her uncle gave Bussey a job in his store and taught him his multiplication tables and a love of learning. Many years later, Angelou met Bussey, who told her, “I am the man I am today because of your Uncle Willie.”

Bussey graduated from Stamps public schools and attended Bishop College in Marshall, Texas, a historically black college. He served in the U.S. Army as a private during World War II. After the war, he settled in Little Rock and organized and led the Veterans’ Good Government Association to encourage other black World War II veterans to actively participate in government. In 1947, he was elected as Little Rock’s “bronze mayor,” an unofficial office designed to give the black community a feeling of participation in local government.

Bussey married Maggie B. Clark on October 6, 1945; they had two sons.

Long active in central Arkansas politics, especially in Little Rock, Bussey was a pioneering black leader in many areas of local and regional public and community service. He was a Mason and an active Shriner, obtaining the Thirty-third Degree. Professionally, he worked as a court investigator. In 1968, he was the first African American elected to serve on the Little Rock City Board of Directors since Reconstruction, serving from 1969 to 1976 and then again from 1979 to 1990. He became the first black deputy sheriff of Pulaski County, serving from 1950 to 1969, and then the first black mayor of Little Rock, serving from November 1981 through December 1982. He also served eight and a half years as vice mayor, longer than anyone else in that position in history. His local focus during these years was involvement of youth and disadvantaged young people in civic and community activities, focusing on leadership and active citizenship. His national focus was on presenting Arkansas—and especially Little Rock—in a positive light, reflecting the community healing that was required following the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School.

Bussey was elected to the board of directors of the Arkansas Municipal League and of the U.S. League of Cities. He was close to most members of the Arkansas congressional delegation, especially Congressman Wilbur D. Mills, and was active in all of Mills’s campaigns, including the “Draft Mills for President” initiative in 1971–1972. He was also close to the Kennedy family, especially Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts.

He organized and produced a television show, Center Stage, and was influential in negotiating the formation of the Black Access Channel 14 in Little Rock.

Bussey also served as president of the Arkansas Lung Association, West Little Rock Rotary Club, Arkansas Livestock Association, Shriners, and Elks. He organized the Junior Deputy Sheriffs, where he managed baseball teams and other activities to keep young people off the streets, and served on the board of directors at St. Vincent Infirmary Medical Center.

Bussey died on June 15, 1996. In addition to the city street in Little Rock, the Charles Bussey Child Development Center in Little Rock also bears his name.

For additional information:

Ault, Larry. “State’s First Black to Win Office Dies.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, June 16, 1996, pp. 1B, 5B.

“Charles Bussey, Jr.” Arkansas Black Hall of Fame. https://www.arblackhalloffame.org/honorees/2006/bussey-jr/ (accessed September 8, 2021).

“First Black Is Selected as Little Rock Mayor.” New York Times, November 28, 1981, p. 24.

Kirk, John A. Beyond Little Rock: The Origins and Legacies of the Central High Crisis. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2007.

———. Interview with Charles Bussey, December 4, 1992. David and Barbara Pryor Center for Arkansas Oral and Visual History. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

———. Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940–1970. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

Persistence of the Spirit Collection. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Kay C. Goss

Alexandria, Virginia

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Politics and Government

Politics and Government Charles Bussey

Charles Bussey

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.