calsfoundation@cals.org

Sweet Home (Pulaski County)

The small, rural community of Sweet Home (Pulaski County) is a majority Black community in Pulaski County. Of more than two dozen communities in Arkansas named Sweet Home to have obtained a post office (done on May 29, 1877), this is the only community to have maintained it to the present. Its Hanger Cotton Gin is Arkansas’s oldest cotton gin on the National Register of Historic Places, dating back to at least the 1870s. From 1890 to 1955, Sweet Home housed Arkansas’s Confederate Soldiers’ Home until it moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County); only two entrance pillars and low parts of the front stone wall remain. Sweet Home had the state’s only Florence Crittenton Home for Black unwed mothers, begun by supporters of the white home in Little Rock, from 1950 to the early 1960s.

When the Union army freed Little Rock’s slaves in 1863, Little Rock’s Wesley Chapel transferred from the Methodist Episcopal, South (MES) to the Methodist Episcopal (ME) Church. The congregation had several local preachers, including Tarlton Hardin, who organized annual Sweet Home camp meetings, leading to the development of the Sweet Home Methodist Episcopal Church and community. By 1874, they had raised $40 and elected church trustees—Hardin, Alfred Saffo, and Samuel Davis—to buy an acre of ground south of the school grounds from a church member, Nelson Burton. They built a church using some of the lumber from cypress trees cut down to clear the land. Its first pastor was Ezra Roberts. A larger, stone church replaced it in 1906, followed by a smaller one in 1952 due to declining membership. At first, this church served all of Sweet Home, but in 1888, Allen Chapel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church began on Highway 365 to the north, and then Greater Zion Hill Baptist Church opened to the south.

For much of its history, Sweet Home consisted mostly of family farms such as those of the Cunninghams, Hangers, or Ratcliffes. W. C. Cunningham’s educated father came from Nashville, Tennessee, in the late 1800s and developed a large farm, which was run by his wife after his death in 1917 until her death in 1940, and then by their son until at least 1987. A community leader, the elder Cunningham became a justice of the peace, had a police force, and held court in his house. German immigrants settled in the area to the south in the late 1800s.

Many African Americans migrated away during the early twentieth century (part of an event now called the Great Migration), but this did not close the Black ME and AME churches in Sweet Home. The Great Depression forced some to return to the land to make a living. Bauxite strip mining (1940s–1960) ravaged much land and left large mounds of dirt and rainwater-filled “blue holes.” Some Black youngsters walked five miles from segregated Little Rock to swim, although a few children and at least one carload of people are known to have drowned in the dangerous open pits. White students were bused from the Central High School campus to a white high school west of Sweet Home on Dixon Road when the Little Rock schools closed for the 1958–59 school year.

In 1963, the Pulaski County School Board phased out Sweet Home’s eighty-year-old wooden-frame elementary school. The Sweet Home Economic Opportunity Center leased the building as a neighborhood study center until the school board decided to sell the building in 1968. Led by Webber Scales Jr., the Sweet Home Community Workers Organization (CWO) bought it for a community center, paying off the note with local fundraising by 1972. Zelma Miller ran the center eleven hours a day, aided by Neighborhood Youth Corps workers in the summers. The Economic Opportunity Agency helped provide classes for pre-school children, tutoring for school children, recreational equipment, and hot lunches to the elderly, while the U.S. Department of Agriculture gave hot meals to children in recreational activities. A weekly Bible class met at the center and helped fund it.

The CWO also developed a volunteer fire department and a water district with fire plugs. The CWO tore down the school to use the land for a fire station with trained volunteers, three trucks, and a new community center. (A subsidiary of Sweet Home’s McGeorge Contracting Co., Inc., the Granite Mountain Mining Company—with local ties since the Hanger Cotton Gin was built in the 1870s by a prominent Little Rock family with rock from the Granite Mountain Quarry—may have helped provide material for the nearby football stadium of the 1970 Wilbur D. Mills University High School.)

In 2006, Chief Elwin “Warhorse” Gillum, leader of a mainly Black Native American tribe from Saint Tammany Parish, Louisiana, bought eight acres near the Sweet Home Cemetery as a temporary home and future retreat center after Hurricane Katrina destroyed the tribe’s homes in 2005. They named the land Chahta Yakni Fallama (“God’s people retreating to the land”), marked by a street sign on Highway 365.

Since 2000, Sweet Home’s population has declined. Its 2010 census designated place population was 849, and the community had few establishments but several boarded up stores and homes. Several churches remained. The CWO had become mostly inactive by the twenty-first century. Elementary students attended either Daisy Bates or College Station schools, then Fuller Middle or Mills High schools on Dixon Road, located beside the Pulaski County Special School District building to the west.

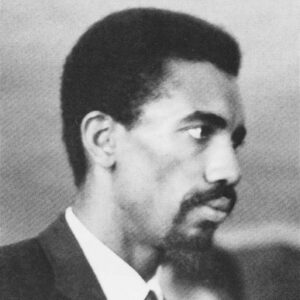

Sweet Home has been home to many notable people. Attorney Scipio Africanus Jones briefly taught school there. Writer Henry Dumas was born in Sweet Home. Sarah Elisabeth Chapline Herndon, Arkansas’s only Red Cross volunteer nurse in the Spanish-American War, was born near Sweet Home. Calvin Comins Bliss, Arkansas’s first lieutenant governor, retired there. Carla Coleman, who became chair of the Black History Commission of Arkansas, grew up near her grandparents and attended church in Sweet Home.

For additional information:

Allen Chapel AME Church Records, 1944–1983, Microfilm MG 00191-00192. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Britton, Nancy. Two Centuries of Methodism in Arkansas: 1800–2000. Little Rock: August House Publishers, 2000.

Gibbens, Byrd. “Some Men of Sweet Home.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 30 (April 1999): 66–73.

Lester, Woodie Daniel. The History of the Negro and Methodism in Arkansas and Oklahoma: The Little Rock–Southwest Conference, 1838–1972. Little Rock: University Press, 1979.

Silva, Rachel. “Pulaski County in the National Register of Historic Places: A History of the Hanger Cotton Gin.” Pulaski County Historical Review 57 (Summer 2009): 69–72.

“Sweet Home Center Fills Needs, Prompts Planning.” Arkansas Gazette, June 18, 1972, p. 12A.

Robert Sherer

Little Rock, Arkansas

Allen Chapel AME Church

Allen Chapel AME Church  Arkansas Confederate Home

Arkansas Confederate Home  Arkansas Confederate Home

Arkansas Confederate Home  Henry Dumas

Henry Dumas  Entering Sweet Home

Entering Sweet Home  First United Methodist Church

First United Methodist Church  Elisabeth Herndon

Elisabeth Herndon  Pulaski County Map

Pulaski County Map  Sweet Home Fire Department

Sweet Home Fire Department  Sweet Home Cemetery

Sweet Home Cemetery  Sweet Home Post Office

Sweet Home Post Office  Sweet Home Street Scene

Sweet Home Street Scene  Sweet Home Street Scene

Sweet Home Street Scene

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.