calsfoundation@cals.org

Folklore and Folklife

When English antiquarian William J. Thoms introduced his new coinage “folk-lore” in 1846, he intended it as a “good Saxon substitute” for “popular antiquities,” a Latinate term that referred to the manners and customs of the “olden time.” Although subsequent folklore scholars have recognized that their subject is an ever-changing, modern phenomenon, the association of folklore with antiquity has often sent folklorists to people and places that seem to lie outside the mainstream of cultural development and where, they assume, a way of life untouched by modernization and globalization endures. In the United States, the “folk” were those who lived in isolation as a result especially of geography but sometimes of ethnicity or another distinguishing factor. Arkansas, especially its Ozark region, appeared to be a fertile field for folklore research, and the first publication on the state’s cultural heritage that used the term “folklore” was apparently an article in the Journal of American Folklore in 1892 by Alice French, writing as “Octave Thanet.” Although containing a hodgepodge of dialect uses, folk beliefs, African-American hymnody, and patent misstatements, the brief article anticipates a long, distinguished history of folklore collection, analysis, preservation, and promotion that includes such luminaries as Vance Randolph, John Quincy Wolf, and W. K. McNeil, as well as such institutions as the Ozark Folk Center in Mountain View (Stone County) and the Delta Cultural Center in Helena-West Helena (Phillips County).

The Concept of “Folklore”

Folklore represents what may be called a society’s “unofficial culture,” much of which is passed on through face-to-face contact with people in one’s immediate reference groups. As unofficial culture, folklore encompasses material culture such as vernacular architecture, arts, and crafts; belief systems; and customary behavior. Moreover, much folklore constitutes a kind of “oral literature” and may range from simple forms such as succinct figures of speech (“crooked as a ram’s horn”) and memorably phrased statements of commonsense wisdom (“Don’t put all your eggs in one basket”) to complex narratives in song (such as ballads and epics) or in the spoken word (myths, legends, and folktales, for example).

Most commentators identify verbal material as folklore on the basis of its oral dissemination, its performance taking place in situations where speaker or singer and audience are in immediate contact. Most folklore—verbal, customary, or material—also has an existence in tradition. This means some of its features are grounded in a continuing heritage of oral performance and customary example. Such features might include the plot outline of a story, aspects of its verbal style, the kinds of situations where it can be related, and body language that accompanies its performance. Because verbal folklore circulates among individuals in oral interactions, it lacks the permanence that writing or other communicative media might produce. Consequently, another trait associated with folklore is variability. Each performance of story, song, or proverb evinces some distinctive elements. Meanwhile, though, some performance features remain constant, and folklore often reflects considerable formularization in diction, style, and theme. Folklore is also sometimes distinguished from other kinds of verbal art by the anonymity of its creator, whose identity may not be known to the people who tell the story or sing the song.

Since Thoms’s coinage, the meaning of “folklore” has varied considerably. A notable indicator of this diversity in meaning is the twenty-one distinct definitions of the subject that appear in the Funk and Wagnalls Standard Dictionary of Folklore, Mythology, and Legend, originally published in 1949. The situation was complicated by the introduction of “folklife,” which came into English usage from the Swedish folkliv in the 1960s. For some people, the terms are synonymous; for others, folklore refers primarily to verbal forms, while folklife encompasses customary and material culture. Another perspective suggests that one term (either folklore or folklife) is more inclusive and subsumes the other.

Folklore in Arkansas

Arkansas’s earliest inhabitants had rich stores of orally disseminated mythology, legends, folktales, songs, and ritual texts—whose images may have survived in graphic and plastic art, including petroglyphs, pictographs, and ceramics such as the ones excavated at such archaeological sites as Casqui near Parkin (Cross County). Native Americans who still inhabited the territory and state when a significant Euro-American presence became apparent also possessed a wealth of traditional folklore and folklife. The first report of that wealth (and apparently the first folklore recorded in what became Arkansas) appears in the accounts of French explorer Jean Bernard Bossu, who spent the winters of 1751–52 and 1770–71 among the Akanças. (An earlier book treating explorations in Arkansas by Jean Francois Dumont includes some tall tales, but they are probably the author’s own inventions, not indigenous traditions.) Bossu described the ritual by which he was adopted into the tribe and various other festivities and games. He also translated the texts of an oration and a poem into the ornate literary style of his era. Subsequent reports and records of Indian folklore from groups whose traditional homeland was Arkansas—including Caddo, Quapaw, and Osage—appear in articles and books by folklorists and anthropologists, many of whom interviewed descendants of the native Arkansans after they had been moved farther west.

Early European and Euro-American impressions of Arkansas often drew upon folk traditions. Stories about the state’s remarkable fruitfulness, for example, incorporated elements from similar boasts and brags in Europe: crops that would grow up overnight and produce gargantuan yields, game and fish both plentiful and compliant, and an environment so healthy that the very water had medicinal properties. The antebellum humorist Thomas Bangs Thorpe drew upon this imagery in his short story “The Big Bear of Arkansas,” published in 1841. When Arkansas failed to live up to its billing, negative folklore developed that exaggerated its failings—again using traditional images and patterns. The song usually known as “The State of Arkansas,” which probably dates from the 1890s, articulates the state’s anti-image that developed. The song’s narrator arrives in Arkansas full of hope that fortune awaits him. He is soon disabused of this illusion when an unkempt, unhealthy-looking Arkansawyer offers him a job draining swampland. After weeks of hard labor on mean rations, the narrator laments, “I never knew what misery was till I came to Arkansas.” Similar negative images in American folksong have attached to the “dreary Black Hills” of the Dakotas, “Nebraska land,” and the abode of the “Lane County Bachelor.” In both positive and negative manifestations, Arkansas’s image is far from unique.

But Arkansas’s reputation as a backwoods state contributed to the attention that folklorists have paid to it. Arkansas’s rich folklore heritage can be sorted in several ways: by genre, ethnicity (Native American, African American, European American, and recently Asian American and Hispanic), or region (generally Delta flatlands and Ozark uplands). Ozark folklore has received the most attention because the mountains seemed to provide an environment for people like those among whom the pioneer folklorists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries expected to find folklore. In fact, several commentators in the early twentieth century—including Vance Randolph, Otto Ernest Rayburn, and Charles Morrow Wilson—argued that people in the Ozarks and their counterparts in the southern Appalachians should be considered America’s “peasantry.” The association of the Ozarks with folklore has been so strong that—largely through the work that Randolph began in the 1920s—the region’s folklore is among the most thoroughly surveyed of any place in the United States. Randolph’s many books and periodical articles—as well as those of other collectors—ensure that Ozark folklore is well represented in the published record.

Verbal Folklore in the Ozarks

Randolph was lured into the Ozarks, where he had vacationed as a child, by the appeal of ballads, particularly the narrative folksongs from England and Scotland that Harvard University professor Francis James Child had anthologized in the late nineteenth century and many of which dealt with knights and ladies in pseudo-medieval settings. Randolph was fascinated that Ozark “peasants” living in the early twentieth century as subsistence farmers in an isolated pocket of the United States were singing songs about British nobility and royalty that could be traced in a few cases to the late Middle Ages. These songs tell pithy, dramatic, often lurid stories of young women seduced by supernatural beings (“Lady Isabel and the Elf-Knight”), intra-family murder (“Edward”), cruel young women who drive rejected suitors to their graves (“Barbara Allen”), and a woman so mean that the devil cannot stand to have her in hell (“The Farmer’s Curst Wife”).

Ozark singers supplemented these old narrative folksongs from the British Isles (known as “Child ballads” for the Harvard professor who edited and numbered the collection) with more recent songs from Britain and Ireland; with indigenous ballads that told stories of Robin Hood-like outlaws, Civil War battles (including the Battle of Pea Ridge), railroad disasters, and other American themes; and with sacred and secular folk lyrics that did not tell stories but conveyed moods or emotions. Randolph worked primarily in the western Ozarks and produced one of the most comprehensive collections of American folksongs from a single American region: the four-volume Ozark Folksongs, which the State Historical Society of Missouri published between 1946 and 1950. A generation later, John Quincy Wolf was collecting ballads and other folksongs in the eastern Ozarks. Both collectors gathered substantial bodies of material and identified important performers of this material. One of Randolph’s most gifted performers of folksongs was Emma Dusenbury of Mena (Polk County). Wolf made contact with Almeda Riddle of Heber Springs (Cleburne County) and the Morris family of Timbo (Stone County). James Morris—as Jimmy Driftwood—became a well-known songwriter and popularizer of Ozark folksongs in the 1950s and 1960s.

Folksongs were the primary lure that drew early collectors to the Ozarks. Instrumental music did not receive as much attention, though several Ozark string bands, featuring skilled fiddlers such as Absie Morrison, made recordings in the late 1920s. Folklorists also found rich resources in other verbal genres in the hills of central and western Arkansas. Randolph collected and published a range of folk narratives. Märchen are long stories of wonder that the general public often calls “fairy tales.” Some of those recorded by Randolph have elements that suggest a tradition going back a millennium. He also recorded many ghost stories (which might localize internationally known themes), accounts of witchcraft (a subject often treated with extreme secrecy in the region), jokes (many of which were too ribald for publication in the 1950s when most of his volumes of stories came out), and tall tales (“lies” in local parlance). Other collectors have gathered historical legends—“folk history”—which preserve local versions of the escapades of figures such as the outlaw Jesse James and of Civil War feuds and skirmishes. Another important kind of folk story is the personal narrative. In the Ozarks, people often relate the adventures they have while hunting or fishing, their religious experiences, and any unusual event that befalls them. Sagas that recount a family’s history and celebrate its patriarchs and matriarchs represent another frequently narrated story type in the Ozarks, one frequently performed at family reunions.

Among other popular verbal folklore forms are riddles—questions usually involving a metaphor or other figure of speech that tests the audience’s verbal skills and knowledge of the farmyard, nature, or other aspects of everyday life. Proverbs—figurative statements that apply time-tested wisdom to particular situations—have been an important method of commenting indirectly on human frailties. Stories, riddles, and proverbs have been couched in a regional dialect that shares vocabulary, pronunciation, and grammatical features with the speech in other parts of the upland South but evinces distinctive traits especially in vocabulary.

Customary and Material Folklore in the Ozarks

Randolph and other students of Ozark folklore have not been interested only in orally disseminated forms. In fact, one of Randolph’s earliest books on the region, The Ozarks: An American Survival of Primitive Society (1931), was an attempt to produce something similar to the ethnographies that anthropologists write when they provide comprehensive overviews of the ways of life of societies at a particular point in their development. Useful documentation of customs in the Ozarks exists. Rites of passage—the customs that accompany an individual’s change in social status—include baptisms, weddings, childbirth, retirement parties, and funerals. Folk beliefs and practices cluster around these events to help the individual make the transition and the community adapt to his or her new identity. For example, wedding customs and beliefs prescribe ways to ensure that the marriage succeeds: a bride and groom must stand with their feet parallel to the planks in the floor; a bride must set off on her right foot after the ceremony; a bride should not cook her own wedding dinner; and a bride should not exhibit her wedding garments before her wedding day.

The annual cycle, based primarily on the agricultural year, is also the focus for much customary folklore. Traditional Ozark farmers have performed many agrarian tasks by the signs of the zodiac, usually expressed in terms of their relationship to parts of the human body (for example, the sign is said to be “in the heart” during the period in late July and August astrologically referred to as Leo). Scheduling tasks might also depend on the phase of the moon, whether waxing or waning. The Christian and national holiday calendars have provided a focus for Ozark folk customs such as “frolics” and “play parties”—the latter for people for whom dancing was religiously proscribed.

Collectors of Ozark folklore found that the customary belief system offered responses to most aspects of life in which humans might not feel fully in control. Illness and injury, for example, might elicit folk scientific responses when people used home remedies based on practical experience and traditional knowledge, especially of the medicinal properties of plants. They could also evoke supernaturally based cures, especially when illnesses were unresponsive to science or were particularly serious. Other situations that might encourage people to turn to folklore included weather prediction, for which Ozark residents developed an array of methods often grounded in experience. Other prognosticative practices were spouse selection (usually by girls eager to know who their future partners would be), an anticipated child’s sex, and a newborn child’s future. Unlike weather lore, which often reflected the results of observations over generations, other kinds of prediction might have a strong element of supernaturalism and might not be taken completely seriously.

Vernacular architecture in the Ozarks has used available materials to construct dwellings whose forms are traditional throughout the upland South. An example is a “dogtrot” house. Built of log or frame and consisting in its most basic form of two large rooms separated by a breezeway, a house of this type provided ample ventilation in the summer. As a family prospered, additional rooms could be added and the breezeway enclosed. Other material folklore in the Ozarks included arts and crafts, many of which had both utilitarian and aesthetic purposes. Specific arts might be gender specific (for example, smithing for men and quilting for women), while others (split-wood basketry) could be done by either. The early collectors of Ozark folklore paid less attention to material culture than to oral literature or customary folklore, but the lack of interest has been compensated by the central role of arts and crafts at venues, such as the Ozark Folk Center, that have preserved and revived many practices.

Folklore in the Delta

While the focus of much folklore attention in Arkansas has been on the Ozarks, the alluvial plain of the Mississippi River has produced an equally rich heritage and one that has perhaps been more varied because of ethnic diversity in the presence of African Americans, Asian Americans, and European Americans in addition to the descendants of Britons whose folklore has been the primary focus of attention in the Ozarks. The relative lack of attention to folklore in the region probably stems from its inhabitants’ not fitting as neatly into the preconceptions of who might constitute the “folk.” But students of folklore have become increasingly attracted by some traditional Delta art forms, especially the blues.

While black folklore in the Delta and elsewhere in Arkansas has analogues in Europe and Africa, it represents a distinct heritage that synthesizes traditions from the two continents with themes and forms that have emerged in the Americas. Black folk narrative encompasses many of the same genres as are found in the Ozarks but stresses somewhat different themes. For example, the trickster figure—a universal character in literature whose physical impotence forces him to rely on wit and strategy to survive and flourish—appears more frequently in tales related by black raconteurs than by their white Ozark counterparts. While occasionally the trickster assumes the guise of Brer Rabbit, more often he is the slave John (or Efan) who must outwit Old Master, a monkey who relies on verbal agility to overcome more powerful jungle beasts, or a nameless man or woman who must negotiate the remnants of Jim Crow discrimination that still characterize some communities. The trickster often takes on the identity of an entertainer, particularly a bluesman, or of a preacher.

Legends in the Delta have responded to traditional supernaturalism that produces ghost stories similar to those in the Ozarks. But the specific history of the Delta, particularly racial violence and natural disasters, has produced distinctive themes. The periodic, devastating floods of the Mississippi River and its tributaries, most famously the Flood of 1927 and flooding in 1937, have yielded a rich store of legendry, and the region’s experience with tornadoes has produced a heritage of tornado lore.

The blues—a lyric folksong form that developed in the Arkansas and Mississippi Delta regions in the late nineteenth century among the first generation of African Americans to come of age after slavery—may be the most widely known folklore form associated with the Arkansas flatlands. Influenced by the field hollers and worksongs that accompanied agricultural labor and by religious music—especially the gospel music that was emerging with it—the blues operates as a commentary on the everyday life of its performers and audience. Although its most frequent topic is the tensions associated with male-female relations, the blues may deal with virtually any concern in the community. It does so succinctly, usually in three-line stanzas in which the first two lines are virtually identical. Blues imagery is concrete and relies extensively on metaphors, which often have sexual connotations. Traditional performance settings for blues have included barbecues, fish fries, and other community celebrations; juke joints—unlicensed clubs run by black proprietors and usually located in rural situations; and street corners. A blues performance in one of these venues is an extemporaneous combination of stanzas. The song itself may not be traditional, but the stanzas that compose it usually come from the store of material that blues performers have been developing for a century. The performer accompanies himself on guitar or is supported by an ensemble that may include lead and rhythm guitars, keyboard, and percussion. Commercial recording of the blues began in the 1920s, and performers associated with Arkansas such as Peetie Wheatstraw (William Bunch), who grew up in Cotton Plant (Woodruff County), and Big Bill Broonzy (William Lee Conley), who lived in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), were appearing on recordings within the next decade.

The 1940s development of King Biscuit Time, a blues radio program broadcast in Helena, represented a watershed for the blues in Arkansas, and one of its founders, Mississippi-born Aleck Miller (who adopted the performance name “Sonny Boy Williamson II”), became an international blues celebrity in the 1950s. Blues continues to flourish and to be promoted at the Arkansas Blues and Heritage Festival (formerly the King Biscuit Blues Festival) in Helena and at other events in the state.

Religious music—including hymns from the late eighteenth century (called “Dr. Watts,” for composer Isaac Watts, in black folk speech), spirituals that developed during slavery times, and gospel music performed by ensembles using four-part harmony or by charismatic soloists such as Rosetta Tharpe (also from Cotton Plant)—added to the folk music soundscape of the Arkansas Delta. Blues and gospel also contributed to the development of commercial rock and roll, many of whose pioneers, including Johnny Cash, Billy Lee Riley, and Sonny Burgess, were Arkansans who recorded just across the Mississippi at the Sun Records studio in Memphis, Tennessee.

Black material culture has also been important in the Delta. Quilt-making has flourished there with at least as much vitality as it has in the Ozarks, and vernacular architectural forms such as the shotgun house mark the cultural landscape. This type of structure, which has antecedents in West Africa, has a floor plan in which rooms are aligned one after another. (One can fire a shotgun through the front door and have the shot emerge out the back door, according to traditional etymology for the name of this house type.) Shotgun houses have provided a principal residence for sharecroppers, black and white, in the Arkansas Delta.

Ethnic Folklore in Arkansas

The influx of Asians—primarily Chinese in the nineteenth century, Vietnamese and Cambodians in the twentieth century—added a new body of traditions to Arkansas folklore. But these populations have remained relatively small, and Italians and Germans have been more prominent. Many of the former came to eastern Arkansas to work at Sunnyside Plantation in Chicot County. Later, Italians formed communities in other parts of the state, including Little Italy in Pulaski County and Tontitown in Washington County. Their influential folklore has included calendar customs such as the erections of St. Joseph’s altars on that saint’s feast day (March 19) and food practices that have emerged from the domestic to the public sphere at parish spaghetti suppers and the annual Tontitown Grape Festival. The state’s growing Hispanic population will continue to add new traditions to the corpus of Ozark folklore. By the beginning of the new millennium, for example, the conjunto, a musical ensemble focusing on the accordion, could be heard performing musica norteña at Cinco de Mayo festivals in parts of the state where Hispanics had become a presence.

Folklore and folklife continue to figure in the lives of Arkansans. Reminders of the traditional heritage of both the Ozarks and the Delta abound as the state uses its image as a folklore-friendly region to attract cultural tourism. Moreover, new folklore continues to develop. While sites where ghostly lights are encountered—for example, in Crossett (Ashley County) and Gurdon (Clark County)—still attract curious thrill-seekers, urban legends (knowledge of which may be global) often have Arkansas settings. Stories of food contaminations, organ thefts, homicidal maniacs, and technology run amok circulate among Arkansans by word of mouth and the Internet. Stories with long histories—such as that of the ghostly hitchhiker who vanishes from the car of the person who has picked her up (a story frequently localized in Arkansas)—take on new identities. In some modern versions, the hitchhiker offers a warning about global warming or another threat to human existence before she vanishes.

Conceived by Thoms and his contemporaries as the focus of their antiquarian interest, folklore retains connections with the past and for some evokes nostalgia for a simpler life. But, in some form, folklore remains vital for all Arkansans.

For additional information:

Burnett, Abby. Gone to the Grave: Burial Customs of the Arkansas Ozarks, 1850–1950. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014.

Burns, Richard Allen. “A Folklife Survey of the Arkansas Delta.” Mid-America Folklore 25 (Spring 1997): 1–13.

Dorsey, J. Owen. “Kwapa Folk-Lore.” Journal of American Folklore 8 (1895): 130–131.

Dorson, Richard M. Negro Tales from Pine Bluff, Arkansas, and Calvin, Michigan. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1958.

Folklore Collection. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

John Quincy Wolf Folklore Collection. Regional Studies Center. Lyon College, Batesville, Arkansas.

LaPin, Deirdre (with Louis Guida and Lois Patillo). Hogs in the Bottom: Family Folklore in Arkansas. Little Rock: August House, 1982.

Masterson, James R. Tall Tales of Arkansaw. Boston: Chapman and Grimes, 1943.

McDonough, Nancy. Garden Sass: A Catalog of Arkansas Folkways. New York: Coward, McCann, and Geoghegan, 1975.

McNeil, W. K., ed. The Charm Is Broken: Readings in Arkansas and Missouri Folklore. Little Rock: August House, 1984.

———. Ghost Stories from the American South. Little Rock: August House, 1985.

McNeil, W. K., and William M. Clements, eds. An Arkansas Folklore Sourcebook. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

Moore, Ramey. “Returning to the ‘Natural State’: Trail Trees and Settler Colonial Conservation in the Arkansas Ozarks.” Human Organization 81 (Winter 2022): 338–347.

Nelson, Sarah Jane. Ballad Hunting with Max Hunter: Stories of an Ozark Folksong Collector. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2023.

“A Northeast Arkansas Ballet Book.” Annotated by W. K. McNeil. Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 30 (December 1999): 179–204.

Otto Ernest Rayburn Papers. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Ozark Folksong Collection. University of Arkansas Libraries Special Collections. http://digitalcollections.uark.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/OzarkFolkSong (accessed July 9, 2023).

Randolph, Vance. Ozark Folksongs. 4 vols. Columbia: State Historical Society of Missouri, 1946–1950.

Randolph, Vance. Who Blowed Up the Church House? and Other Ozark Folk Tales. New York: Columbia University Press.

Randolph, Vance (with George P. Wilson). Down in the Holler: A Gallery of Ozark Folk Speech. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953.

Randolph, Vance, and Gordon McCann. Ozark Folklore: An Annotated Bibliography. 2 volumes. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1987.

Rayburn, Otto Ernest. Ozark Country. New York: Duell, Sloan, and Pearce, 1941.

Tallman, Richard, and Laurna Tallman. Country Folks: A Handbook for Student Folklore Collectors. Batesville: Arkansas College Folklore Archive Publication.

Vance Randolph Collection. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

William M. Clements

Arkansas State University

"Arkansas Traveler"

"Arkansas Traveler"  "The Battle of New Orleans," Performed by Jimmy Driftwood

"The Battle of New Orleans," Performed by Jimmy Driftwood  Big Bear of Arkansas Illustration

Big Bear of Arkansas Illustration  "Big Bill Blues," Performed by "Big Bill" Broonzy

"Big Bill Blues," Performed by "Big Bill" Broonzy  Jimmy Driftwood

Jimmy Driftwood  Emma Dusenbury

Emma Dusenbury  "Fattening Frogs for Snakes," Performed by "Sonny Boy" Williamson

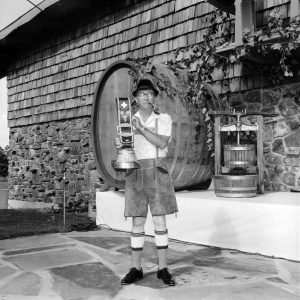

"Fattening Frogs for Snakes," Performed by "Sonny Boy" Williamson  Granata Winery

Granata Winery  Head Pot

Head Pot  Robert Lockwood Jr.

Robert Lockwood Jr.  Ozark Folk Center

Ozark Folk Center  Ozark Folk Center Blacksmith

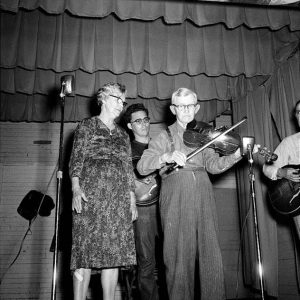

Ozark Folk Center Blacksmith  Vance Randolph with Musicians

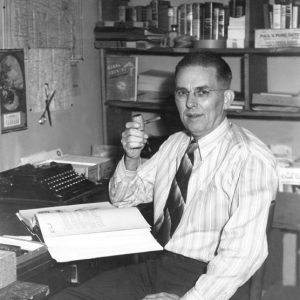

Vance Randolph with Musicians  Otto Ernest Rayburn

Otto Ernest Rayburn  Almeda Riddle

Almeda Riddle  "Rock Me," Performed by Sister Rosetta Tharpe

"Rock Me," Performed by Sister Rosetta Tharpe  Herman Wiederkehr

Herman Wiederkehr  Charles Morrow Wilson

Charles Morrow Wilson

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.