calsfoundation@cals.org

University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff (UAPB)

The University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff (UAPB) began as Branch Normal College, which sought to accommodate the higher-educational needs of Arkansas’s African American population. UAPB is the alma mater of such notable figures as attorney Wiley Branton Sr., Dr. Samuel Kountz, and attorney John W. Walker. It is part of the University of Arkansas System.

State senator John Middleton Clayton sponsored a legislative act calling for the establishment of Branch Normal College, but it was not until 1875 that the state’s economic situation was secure enough to proceed with it. That year, Branch Normal was established as a branch of Arkansas Industrial University, now the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County). Its primary objective was educating Black students to become teachers for the state’s Black schools. Governor Augustus Hill Garland, Arkansas Industrial University board chairman D. E. Jones, and Professor Wood Thompson hired Joseph Carter Corbin in July 1875 to make a determination about locating Branch Normal in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) because of the town’s large Black population and its place as the major economic center in south-central Arkansas. Corbin was subsequently elected as principal at a salary of $1,000 a year. The first class consisted of seven students. During the year, seventy-five to eighty students were enrolled, but the average attendance was forty-five to fifty the last three months of the school year.

Rumors about high fees and the school being a political experiment made recruitment of students difficult. Therefore, a policy was developed that allowed two types of students to enroll and attend: beneficiaries and pay students. The policy provided for each county to send one to fourteen beneficiaries to Branch Normal, and students were appointed by the county judge. Admission required a commitment from each student that he/she would teach in Arkansas for two years after graduation. Pay students were charged a one-time tuition fee for admission.

Several setbacks occurred that delayed the actual opening of the school. The first building was an old frame house in need of much repair, but repairs were delayed because of illness among the workers. Lumber and furniture were ordered for the new building, but the boat carrying them sank in the river.

Because Corbin saw that the need for basic education was crucial, he set up a preparatory department for those who were academically unprepared for college studies. He was the only faculty for several years, but the enrollment grew to 145 in 1881. Realizing that he could only do so much, he utilized the more advanced students as teaching assistants. His annual request for a full-time paid assistant was not granted until 1883.

In 1889, the Branch Normal Committee granted $500 for a library and $500 for one assistant teacher, Rufus C. Childress, who was the first graduate of Philander Smith College. In January 1882, the school was moved into a permanent building with four classrooms. In 1889, Corbin recommended to the governor that vocational and industrial courses be added to the curriculum. The recommendation was approved, and the agricultural and mechanical departments emerged. During the first sixteen years, dormitories for men and women were built, and the faculty was expanded.

The Morrill Act of 1890 made the school a land grant institution for Black students. Although the act specified equitable division of monies among the white and African American schools, Arkansas was allowed to give eight-elevenths to Arkansas Industrial University and three-tenths to Branch Normal.

Corbin spent twenty-seven years as principal of the only tax supported institution of higher education for African Americans in Arkansas. However, after increasing conflict with the board of the school and the state legislature, he was dismissed in 1902. Isaac Fisher succeeded Corbin as principal, and he believed, as did Booker T. Washington, that industrial education was best for African Americans. This caused a shift in the school’s focus. The bachelor’s degree was removed because no faculty members held degrees; no student had received the degree since 1903. The school began to provide only elementary and secondary education to students, at which point the board redirected the college back to its original purpose—to train teachers.

Fisher resigned in June 1911, and William Stephen Harris, a white man, was named as supervisor of Branch Normal, while Frederick Venegar was named principal. Their tenure was unpopular. A student strike broke out on March 22, 1915, provoked by student outrage at the behavior of Harris, who had recently given a package containing black silk stockings to a female student—evidently part of a pattern of inappropriate behavior by Harris toward students for years. The board supported Harris and Venegar, but community leaders in Pine Bluff called for their ouster. Following their resignations, Jefferson Ish was elected as head of the college and, during his first year, he started a summer school for teachers. Legislative Act 568 of 1921 changed the name of the college to Agricultural, Mechanical, and Normal School, signifying a new emphasis upon agricultural studies.

When Ish resigned in 1921, Charles Smith became principal for one year; he was followed by Robert Malone, who was able to strengthen the curriculum so that, by 1926, 411 students were enrolled, twenty-one in junior college courses, and the school was granted junior college status. In 1927, the school became Agricultural, Mechanical, and Normal College (AM&N) and was made independent of UA, with Governor John Martineau appointing an independent board of trustees for the college.

Under the administration of the next superintendent, Dr. John Brown Watson, plans were completed for the new campus. He began a free “night school,” offering courses in cooking, sewing, woodworking, automobile mechanics, and arithmetic. When Watson died in 1942, the enrollment was 474.

Branch Normal became a standard four-year college in 1929. In 1933, residences for instructors and a gymnasium were built, and two more dormitories and a library were added in 1938. Twenty-five huts and five prefabricated dormitories were added. In the summer of 1947, a number of temporary buildings were constructed: an infirmary; a high school (which was also a laboratory school for education majors); music, science, agricultural, and mechanical arts buildings; and a dining hall.

Dr. Lawrence A. Davis was appointed the next president in 1943. Under his administration, the physical plant doubled. An agricultural laboratory was established, as well as a station of the Arkansas Archeological Survey. He expanded the academic programs and changed the organizational structure to three areas: agriculture and technology, arts and sciences, and teacher education. Accreditation from North Central Accreditation of Colleges and Schools was granted in 1950. In cooperation with UA and the Arkansas Archeological Survey, the college farm and agriculture lab expanded services and research facilities. A major addition was the aquaculture project. The music department added a degree in music technology.

The 1971 session of the state legislature ordered the merger of UA and AM&N into one system. On July 1, 1972, this merger was complete, and AM&N was designated the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. Fearing a loss of identity, many Black supporters, citizens, and faculty opposed the merger. They filed a suit challenging it on the grounds that it was unconstitutional because there was no requirement for educational opportunities and equal treatment under the all-white board of trustees at UA, but the suit was unsuccessful. Davis accepted the new position of chancellor in June 1972; he frequently had to adjust finances for the college to survive.

In November 1972, the university experienced campus turmoil when Student Government Association president John Crenshaw organized a boycott of classes in protest of the leadership of the college. He and other students believed that the interests of the African American student body were not being properly addressed by the administration. The leaders of the boycott called for the dismissal of Chancellor Davis and three additional administrative staff. The boycott lasted for approximately a week before the campus returned to normal. Davis resigned several weeks later.

Dr. Herman B. Smith Jr. was appointed chancellor in 1974. During his tenure, the school faced a lawsuit alleging that administrators perpetrated sexual discrimination against, and the sexual harassment of, the faculty. Smith resigned as chancellor in 1981, before the resolution of the suit in court. In August 1982, Judge Henry Woods ruled that the university illegally discriminated against female faculty members by “practices of sexual discrimination too blatant to overlook,” and he ordered several remedies for the situation. This decision was upheld by the U.S. Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Smith was replaced by Dr. Floyd V. “Vic” Hackley, who placed emphasis on students working to master the necessary exams to secure entrance into graduate school. He resigned in 1985 and was replaced by Dr. Charles Walker, who worked to allow research students to participate in off-campus training programs at such institutions as the National Toxicological Research Center (NTRC) and the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS). However, he was cited for financial mismanagement of the university. In his defense, he noted that the university had not received the necessary appropriations to cover increases in expenditures, especially when compared with other universities in the system, but an investigation by the joint legislative committee resulted in his resignation, as well as those of several key administrators and a citation against the athletic department for mismanagement. Dr. Carolyn Blakely served as interim chancellor from June until September 1991, when Lawrence A. Davis Jr., son of Lawrence A. Davis Sr., was named chancellor. He announced his retirement on March 22, 2012. Laurence B. Alexander was subsequently named chancellor, taking office on July 1, 2013.

UAPB, the mascot of which is the golden lion, operates off-campus sites at Lake Village (Chicot County), Marianna (Lee County), North Little Rock (Pulaski County), and Lonoke (Lonoke County). It offers bachelor’s degrees in agriculture, fisheries and human sciences, arts and sciences, business and management, education, and rehabilitation services. The graduate program awards the master of education and the master of science degrees, including aquaculture and fisheries and addiction studies. In 2011, the Arkansas Higher Education Coordinating Board approved a doctorate in aquaculture and fishers for UAPB, the first doctoral program at the university.

CHI St. Vincent announced in October 2022 that it was making a $1.1 million gift to UAPB’s nursing department to fund a five-year partnership to address the national nursing shortage.

Officials with the U.S. Department of Education and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) reported in September 2023 that a number of states, including Arkansas, had underfunded land-grant Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) like UAPB for decades, leading to a disparity of more than $12 billion with compared with historically white 1862 land-grant institutions in the nation. Six states—Arkansas, Florida, Maryland, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia—have not taken advantage of the one-to-one federal match funding for the 1890 land-grant HBCU institutions in recent years but did so for the 1862 land-grant institutions. From 1987 to 2020, UAPB was underfunded in state-appropriated funds by an estimated $330.9 million.

In the fall of 2023, the enrollment was 2,117.

For additional information:

Chambers, Frederick. “Historical Study of Arkansas Agricultural, Mechanical, and Normal College, 1873–1943.” EdD thesis, Ball State University, 1970.

Davis, Lawrence Arnett. “A Comparison of the Philosophies, Purposes, and Functions of the Negro Land-Grant Colleges and Universities with Emphasis upon the Program of the Agricultural, Mechanical, and Normal College, Pine Bluff, Arkansas.” EdD thesis, University of Arkansas, 1960.

McGee, Holly Y. “‘It Was the Wrong Time, and They Just Weren’t Ready’: Direct-Action Protest in Pine Bluff, 1963.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 66 (Spring 2007): 18–42.

Neal, Edna LaJoyce Devoe. “Changes at the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff Following Merger into the University of Arkansas System.” EdD thesis, Indiana University, 1978.

Rothrock, Thomas. “Joseph Carter Corbin and Negro Education in the University of Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 30 (Autumn 1971): 277–314.

“UAPB Honors 150 Years of Excellence with Professor Joseph Carter Corbin Day.” UAPB News, September 28, 2023. https://uapbnews.wordpress.com/2023/09/28/uapb-honors-150-years-of-excellence-with-professor-joseph-carter-corbin-day/ (accessed March 20, 2024).

University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. https://uapb.edu/ (accessed March 20, 2024).

Wheeler, Elizabeth L. “Isaac Fisher: The Frustrations of a Negro Educator at Branch Normal College, 1902–1911.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 41 (Spring 1982): 3–50.

Othello Faison

Little Rock, Arkansas

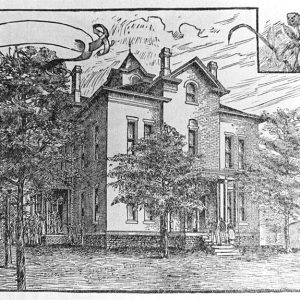

Branch Normal College

Branch Normal College  Caldwell Hall

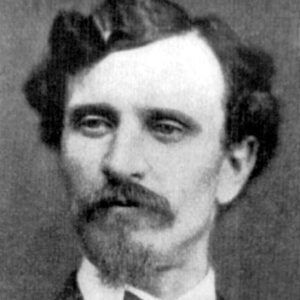

Caldwell Hall  John Clayton

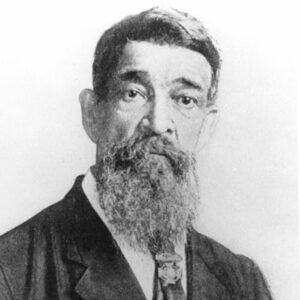

John Clayton  Joseph Corbin

Joseph Corbin  Joseph Carter Corbin Day

Joseph Carter Corbin Day  UAPB Campus Grounds

UAPB Campus Grounds  UAPB Clock Tower

UAPB Clock Tower  UAPB Dawson-Hicks Dorm

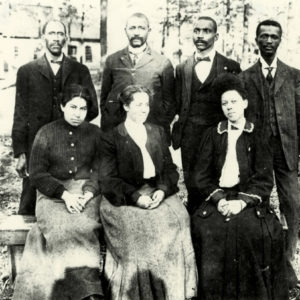

UAPB Dawson-Hicks Dorm  UAPB Faculty

UAPB Faculty  UAPB Lion

UAPB Lion  UAPB Sign

UAPB Sign  University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff Clock Tower

University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff Clock Tower  Walker Center

Walker Center  John Brown Watson

John Brown Watson

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.