calsfoundation@cals.org

Arkansas Tech University

Arkansas Tech University is a public, coeducational, regional university located in Russellville (Pope County). The university offers programs at both baccalaureate and graduate levels.

The institution that became Arkansas Tech University had its origins in an early twentieth-century program known as the Country Life Movement. Designed to reverse the decline in rural life in America, the movement was part of the larger Progressive movement. The driving force for the establishment of agricultural schools in the state was the Farmers Educational and Cooperative Union, a more moderate heir to the Populists and associated agrarian organizations of the late nineteenth century. Spurred on by the Farmers’ Union, the Arkansas legislature in 1909 passed Act 100 to establish a “State Agricultural School” in four districts around the state. Competition for the site of the Second District School was intense. Interested towns had to pledge a minimum of $40,000 and a site of not less than 200 acres. On February 10, 1910, Russellville was chosen over Ozark (Franklin County), Fort Smith (Sebastian County), and Morrilton (Conway County). The decision may have been influenced in part by the town’s pledge to offer free electricity and water for three years. The sites chosen for the other district schools were Jonesboro (Craighead County), Magnolia (Columbia County), and Monticello (Drew County).

The schools were initially known by their district designations. The Jonesboro school (today’s Arkansas State University) was the First District Agricultural School, Russellville (today’s Arkansas Tech University) was the Second District Agricultural School, Magnolia (today’s Southern Arkansas University) was the Third District Agricultural School, and Monticello (today’s University of Arkansas at Monticello) was the Fourth District Agricultural School. All the institutions were initially secondary schools (the equivalent of today’s high schools), but unlike many other Southern agricultural schools, which were essentially regular high schools that provided some agricultural education, the Arkansas schools from the beginning devoted themselves largely to advancing agricultural education.

The Second District Agricultural School opened for classes in the fall of 1910 with 186 students. Enrollment jumped to 350 by the 1913–14 academic year. But the institution’s early years proved to be difficult ones. Funding problems and declining enrollment, particularly during the years of American involvement in World War I, plagued the school. The institution rebounded in the postwar years under the energetic leadership of President Hugh Critz, who took over as president in August 1918 and served until the spring of 1923. College classes were added in 1922, and by the 1924–25 school year, the Second District School was providing instruction to students from the rank of high school freshmen to college seniors.

In February 1925, the legislature decided to change the names of the four agricultural schools. All others became Agricultural and Mechanical (A&M) schools, but the Second District School, in an effort to remain free from the normal (education) courses being offered at Conway (Faulkner County), became Arkansas Polytechnic College (called “Tech” for short). The word “polytechnic” denoted an institution of higher education offering courses at degree or below, especially in vocational subjects. Despite the name change and the desire to be distinct from its neighboring institution in Conway (what is now the University of Central Arkansas), the focus of education at the Russellville campus gradually changed from agricultural education to teacher training and the liberal and fine arts. In 1929, the school was officially accredited as a junior college by the nation’s principal accrediting agency, the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools.

The onset of the Great Depression adversely affected the already precarious financial condition of the state’s institutions of higher learning. After a brief fall-off, enrollment at the Russellville school increased under the leadership of James Richard (J. R.) Grant and even more during the latter years of the Great Depression, growing from its previous all-time high of 482 students in 1929–30 to 758 by the fall of 1940. In 1932, Joseph W. Hull began his lengthy tenure as president of the college. Hull was an accomplished vocational agriculture teacher at Danville High School who had previously been named Master Teacher of Vocational Agriculture in Arkansas and whose Future Farmers of America chapter had been named the best in the nation.

Hull took over as president in the midst of troubled times for the institution. Because of financial difficulties associated with the Depression, the legislature had discussed abolishing the agricultural schools it had created barely twenty years earlier. Under Hull’s leadership, the college weathered that storm only to be confronted by a different but equally dangerous threat with the onset of American involvement in World War II. Even before the United States entered the war, 104 members of Tech’s two National Guard units (one out of every four male students on campus) were ordered to mobilize for a year’s training at Fort Bliss, Texas, beginning in January 1941. The group included twenty-five members of the football team, all but one letterman on the basketball team, the entire track team, and eleven of fourteen student councilmen. In February 1941, Life magazine ran a pictorial feature article on the group’s last day on campus and the school’s efforts to honor them.

The war took a devastating toll on Tech. Enrollment dipped to a mere 133 students in the fall of 1943, the second lowest total in the institution’s thirty-three-year history. To offset the dramatic drop in tuition revenue, the college actively sought government contracts to serve as a military training facility. The effort succeeded when the institution was awarded generous contracts to train elements of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAACs) and naval air personnel.

The end of World War II and the subsequent passage of the GI Bill resulted in a sharp increase in enrollment in the immediate postwar period. In the fall semester of 1946, 1,493 students were enrolled, more than doubling the previous year’s figure of 687. Enrollment stayed above 1,000 for the remainder of the decade but fell off again in the first half of the 1950s. In March 1951, Arkansas Polytechnic College was accredited as a four-year college by the North Central Association.

By 1955, enrollment once again topped 1,000 and increased slowly but steadily throughout the next decade, topping 2,000 for the first time in 1965. Two years later, Hull announced his resignation, ending thirty-five years as president of the institution. During his tenure, the school grew from seventeen major buildings to forty-six, and enrollment increased from 447 to 2,466.

In April 1967, the board of trustees selected George L. B. Pratt, director of institutional research at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County), to be the school’s ninth president. Pratt quickly announced his intentions to focus the school’s curriculum on technology and leisure science and to change some long-standing policies regarding faculty relations. Faculty opposition to Pratt’s plans soon developed, and his five-year tenure was marked by controversy and conflict. His resignation in 1972 and the subsequent election of Kenneth Kersh as president in December of that year helped quiet the controversy. Kersh had been the chairman of the Department of Education at Hendrix College. In 1976, Arkansas Polytechnic College officially became Arkansas Tech University, and the school awarded its first graduate degrees the next year. But neither the new president, the name change, nor the granting of graduate degrees alleviated the institution’s chronic financial problems. Enrollment growth also remained relatively static through the mid-1970s, only reaching 3,000 in the fall of 1980 and remaining flat throughout much of the subsequent decade. Kersh’s tenure as president ended in 1993, making it the second-longest tenure in the institution’s history.

That same year, Robert C. Brown, vice president of academic affairs at Missouri Southern State University in Joplin, became Tech’s eleventh president. Enrollment continued to decline, bottoming out at 4,238 in the 1997–98 school year. Under Brown’s leadership, the university initiated its first systematic attempt at recruiting students. By the fall of 1999, the school reached a record enrollment of 4,840. Arkansas Tech established a new enrollment record in each subsequent year through fall 2012. Enrollment passed the 5,000 level for the first time in 2000 and 6,000 only three years later. Arkansas Tech’s enrollment went over 7,000 in 2006, 8,000 in 2009, 9,000 in 2010, and 10,000 in 2011. A more selective admissions policy also resulted in a dramatic rise in the ACT scores of entering freshmen, with those scores exceeding both the state and national averages for eighteen consecutive years through fall 2012. After Brown’s retirement, Robin Bowen became the twelfth president in 2014. Bowen was the first woman to lead a four-year public college in Arkansas. Also in 2014, the university was granted the ability to offer doctoral programs by the Arkansas Department of Higher Education (ADHE). In 2023, Bowen was fired (terminated without cause) by the board of trustees two months after beginning a medical leave of absence.

Arkansas Tech sponsors intercollegiate athletic programs that participate in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division II Gulf South Conference. The men’s teams are known as the Wonder Boys, and the women’s teams as the Golden Suns.

Since 1995, the university has invested more than $210 million in construction, renovations, and instructional equipment, resulting in a complete overhaul of the school’s physical appearance. One of the most significant improvements was the addition of the Ross Pendergraft Library and Technology Center, which opened in June 1999. Other new facilities constructed since 1995 include the Doc Bryan Student Services Building (named for legislator and alum Doc Bryan), University Commons on-campus apartments, Norman Hall (home of the Arkansas Tech Department of Art), Baswell Techionery (a new student union), three new residence halls (Baswell Hall, Nutt Hall, and the M Street Residence Hall), Thone Stadium at Buerkle Field, the Chartwells Women’s Sports Complex, and Rothwell Hall—a new 60,000-square foot classroom building that also houses the College of Business and the Roy and Christine Sturgis Academic Advising Center. In 2003, Arkansas Valley Technical Institute in Ozark merged with Arkansas Tech, becoming Arkansas Tech University-Ozark Campus.

Arkansas Tech is home to the first emergency management degree programs in the world to be accredited by the Foundation on Higher Education in Disaster/Emergency Management and Homeland Security. Tech is one of only two public universities in Arkansas to offer accredited programs in both mechanical engineering and electrical engineering. Every degree program at Arkansas Tech that is eligible for accreditation has either achieved accreditation or is in the process of doing so. In 2015, Tech began offering a Doctor of Education degree program in school leadership.

In the fall of 2020, 10,866 students were enrolled at Arkansas Tech.

For additional information:

Arkansas Tech University. http://www.atu.edu/ (accessed June 15, 2023).

DeBlack, Thomas A. A Century Forward: The Centennial History of Arkansas Tech University. Marceline, MO: Walworth Publishing Co., 2016.

Walker, Kenneth R. History of Arkansas Tech University, 1909–1990. Russellville: Arkansas Tech University, 1992.

Willis, James F. “The Farmers’ Schools of 1909: The Origins of Arkansas’s Four Regional Universities.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 65 (Autumn 2006): 224–249.

Thomas A. DeBlack

Arkansas Tech University

Arkansas Tech University Museum

Arkansas Tech University Museum Caraway Hall (Arkansas Tech University)

Caraway Hall (Arkansas Tech University) Education, Higher

Education, Higher Girls Domestic Science and Arts Building (Arkansas Tech University)

Girls Domestic Science and Arts Building (Arkansas Tech University) Hall, B. C.

Hall, B. C. Hughes Hall (Arkansas Tech University)

Hughes Hall (Arkansas Tech University) Williamson Hall (Arkansas Tech University)

Williamson Hall (Arkansas Tech University) Wilson Hall (Arkansas Tech University)

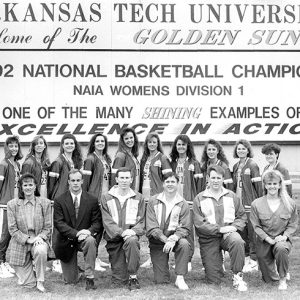

Wilson Hall (Arkansas Tech University) Arkansas Tech's Women's Basketball Team

Arkansas Tech's Women's Basketball Team  Arkansas Tech University

Arkansas Tech University  Arkansas Tech University Museum

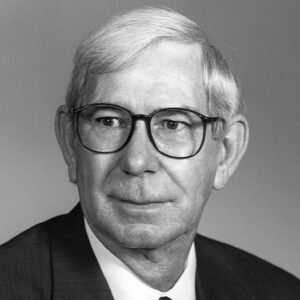

Arkansas Tech University Museum  Robert C. Brown

Robert C. Brown  Caraway Hall

Caraway Hall  Caraway Hall

Caraway Hall  Hugh Critz

Hugh Critz  Girls Domestic Science and Arts Building

Girls Domestic Science and Arts Building  J. W. Hull

J. W. Hull  Kenneth Kersh

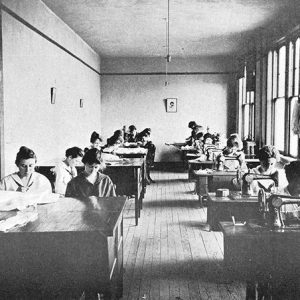

Kenneth Kersh  Second District Agricultural School Domestic Science

Second District Agricultural School Domestic Science  Second District Agricultural School Football Team

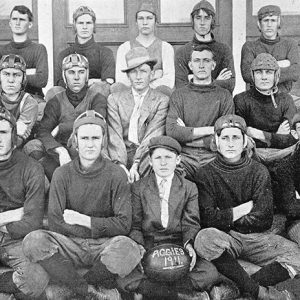

Second District Agricultural School Football Team  Second District Agricultural School Main Building

Second District Agricultural School Main Building  Tech 1934 Homecoming

Tech 1934 Homecoming  Tech Campus in 1960

Tech Campus in 1960  Tech Farm

Tech Farm  Tech Men's Basketball

Tech Men's Basketball  Tomlinson Hall

Tomlinson Hall  Williamson Hall

Williamson Hall  Wilson Hall

Wilson Hall

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.