calsfoundation@cals.org

Music and Musicians

Arkansas has long been among the most significant contributors to the nation’s musical foundation, serving as fertile ground for the development of multiple genres as well as being native home to some of the best-known and influential musicians, singers, songwriters, and songs that the world has known. Much of this is due to the state’s geography—both its diverse landscape and populace and its proximity to key musical hubs and regions in the nation.

Pre-European Exploration through the Nineteenth Century

“From the first, music mattered. You can even see it in what the archaeologists find…fragments of cane flutes and whistles older than Columbus,” wrote Robert Cochran in his history of Arkansas music, Our Own Sweet Sounds: A Celebration of Popular Music in Arkansas. “But you can’t hear this music, and until the first explorers published their accounts in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, you couldn’t even read about it. The Osage drums, the leg rattles of Caddo dancers, the voices of Quapaws raised in song—all is silence.”

Cochran traced what could be the earliest reference to Arkansas music to European explorers encountering Native Americans in the state on multiple occasions in the 1680s. Other accounts are sparse and isolated to settlements such as Arkansas Post, Washington (Hempstead County), and scattered outposts along trade routes such as the Arkansas River and the Southwest Trail.

Perhaps the most famous piece of music from this period referencing the state is “The Arkansas Traveler.” The tune may or may not have been written in Arkansas, but, as Cochran wrote, “By 1845 it was known as a fiddle tune and in 1849 it was reported as the name of a race horse and the most popular dance tune in [the resort town of] Hot Springs.” The tune eventually spawned a popular dialogue as well as a stage drama of the same name and, later, famous Currier & Ives engravings of two paintings by Arkansas painter Edward P. Washbourne: The Arkansas Traveler and The Turn of the Tune.

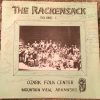

Cochran also noted that there were strong Ozark Mountain folk music and African-American musical traditions in Arkansas in the 1800s, but very little of either was documented. Exceptions include Emma Dusenbury of Baxter County, who recorded 116 songs with the Library of Congress and sang at the Arkansas centennial celebration in 1936, and vaudeville star Essie Whitman of Osceola (Mississippi County), who was one of the Whitman Sisters.

Early Twentieth Century and Radio

The advent of radio in the 1920s enabled musicians, in Arkansas and around the world, to make their marks far from home. Music was a natural fit for the aural medium, and, by 1925, Arkansas had stations licensed in Little Rock (Pulaski County), Fayetteville (Washington County), Hot Springs (Garland County), and Fort Smith (Sebastian County), joining the original WOK in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County).

Plenty of early talent found fleeting fame on the airwaves of stations that, by the 1930s, were scattered around the state. Programs found on 10,000- to 50,000-watt “clear channel” AM radio stations with far-reaching signals proved most influential on the future artists from Arkansas, often musicians and singers who chose musical performance as a way out of the cotton fields.

The National Barn Dance on WLS out of Chicago, Illinois, gave Ruby Blevins (a.k.a. Patsy Montana) of Beaudry (Garland County) her first taste of national fame. WLS would also pick up the Lum and Abner program starring comedians Chester Lauck and Norris Goff of Mena (Polk County), and it hosted comedian, radio host, and banjo player Benjamin “Whitey” Ford of Little Rock—perhaps best known as the Duke of Paducah.

Shreveport radio station KWKH’s Louisiana Hayride served as a showcase for famed Arkansas singers and musicians such as Johnny Cash of Kingsland (Cleveland County), Lefty Frizzell of El Dorado (Union County), and Floyd Cramer of Huttig (Union County), while The Grand Ole Opry aired on WSM out of Nashville, Tennessee.

These and other programs of the day served as something of a model for Arkansas’s most famous and longest-standing radio broadcast. In November 1941, Helena (Phillips County) businessman Sam Anderson and a group of business partners put KFFA on the air. They were soon approached by blues musicians Sonny Boy Williamson of Helena and Robert Lockwood Jr. of Turkey Scratch (Phillips County) about the possibility of letting them play live on the air as a way to advertise nightly appearances around the area. Anderson told them they would need a sponsor and put them in touch with Interstate Grocery Company owner Max Moore, who had been considering an advertising campaign for one of his products, King Biscuit Flour.

The fifteen-minute King Biscuit Time program aired live from the Floyd Truck Lines building with Lockwood, Williamson, and a rotating cast of musicians performing as the King Biscuit Entertainers. The program was so popular that Moore soon re-branded another product as Sonny Boy Cornmeal. As of 2013, the program airs daily from the Delta Cultural Center in Helena-West Helena (Phillips County) on KFFA with longtime host “Sunshine” Sonny Payne.

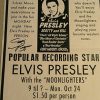

Later in the 1940s, Williamson briefly migrated upriver to KWEM in West Memphis (Crittenden County), a station that hosted musicians who would pay to play live in the studio. The exposure worked to boost the careers of many musicians, including James Cotton of West Helena (Phillips County), Pat Hare of Cherry Valley (Cross County), and Robert Nighthawk of Helena. The station also influenced future trends. Noted figures from Elvis Presley to the Memphis Horns’ Wayne Jackson of West Memphis to Albert King of Osceola have said that the music they heard on KWEM influenced their own careers.

The blues music that was a staple for these and many other radio stations around the Mississippi Delta region was highly influential and helped define the sounds of other genres. These include rhythm and blues (R&B), rock and roll, and country music, all of which would frequently borrow the song structure and phrasing of early Delta blues heard on recordings by the likes of Peetie Wheatstraw of Cotton Plant (Woodruff County)—best remembered for his direct influence on Robert Johnson, who, in turn, served as a musical mentor to Robert Lockwood Jr. when Johnson lived with Lockwood’s mother near Helena, which served as the de facto capital of blues music in the Delta for roughly three decades, beginning in the 1920s.

Gospel also had an impact on these genres of music, and it is the style in which “Sister Rosetta” Tharpe of Cotton Plant got her start. She was four years old when she began performing as a singer and guitarist alongside her mandolin-playing mother at tent revivals around the South. It was only after moving north that she began to play blues, jazz, and R&B publicly. Her 1945 hit “Strange Things Happening Every Day” is often cited as the first rock and roll record. The song was later covered by Johnny Cash, who said Tharpe was his favorite singer when he was a child.

By this time, one of the most important figures in the history of Arkansas music was in New York paying his dues. Songwriter, musician, band leader, and jump blues pioneer Louis Jordan of Brinkley (Monroe County) was born in 1908 into a musical household and studied at Arkansas Baptist College in Little Rock before he left the state to pursue a career that—for nearly a decade beginning in 1942—would see him dominate the R&B charts as the “King of the Jukebox.”

With his 1943 hit “Ration Blues,” Jordan became the first Black musician to achieve “mainstream” crossover success on both the pop and country charts. Jordan’s influence was as broad as it was deep. He has been called the “Father of Rhythm & Blues” and the “Grandfather of Rock ’n’ Roll” by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (he was inducted in 1987) and has been cited as a key influence by fellow musical legends including Chuck Berry, B. B. King, Bob Dylan, and James Brown.

In 1937, a central Arkansas songwriter penned the lyrics one of the best-known and most-covered songs ever written. Luther G. Presley was born in rural Faulkner County and wrote hundreds of songs for Little Rock’s Central Music Company. His most famous contribution to the world of music would be the words to the song “When the Saints Go Marching In,” written while working in Pangburn (White County) for the renowned Stamps-Baxter Music Company, based in Dallas, Texas.

Popular Music in the Post–World War II Era

The roughly three decades following World War II became the most important period for music in Arkansas, both in terms of the number of artists and other musical figures hailing from the state as well as the music they produced during this time.

Journalist and Arkansas music historian Stephen Koch, host of the NPR-affiliated radio program Arkansongs, wrote, “It’s literally impossible to overstate the significance of this period—both in terms of the product of our fellow Arkansawyers as well as the deep and lasting marks they left—on the music world. The number of important players in the music industry rivaled that of nearly any other state, and their impact and significance may exceed it. The global influence that they had is truly staggering, especially when one considers how little credit the state has traditionally gotten. It cannot be denied that Arkansas has had a tangible and disparate role in shaping the record collection of almost anyone who has one.”

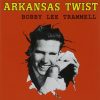

It was across the Mississippi River in Memphis, Tennessee, that artists began building upon the foundation of Tharpe’s early work, laying the groundwork for rock and roll. Much of this was done at Sun Records, where artists like Cash, Billy Lee Riley of Pocahontas (Randolph County), and Sonny Burgess of Newport (Jackson County) found a home, however briefly. Riley and Burgess continued to perform rockabilly music, often in venues along a storied stretch of Arkansas highway now known as Rock ’n’ Roll Highway 67.

Cash, who had moved to Dyess (Mississippi County) with his family as a young boy, joined fellow Memphis-based Sun Records alumni Charlie Rich of Colt (St. Francis County) and Conway Twitty of Helena (who had already sat atop the rock and pop charts) in pursuing their ambitions in Nashville, Tennessee, as country singers. All three achieved legendary status, while Cash transcended boundaries to become a cross-cultural icon to his generation and those to come. He was the recipient of twenty Grammy Awards (most coming late in his career and some awarded posthumously), Kennedy Center honors, and the National Medal of Arts. He is a member of the Country Music, Rockabilly, Gospel, Rock and Roll, and Songwriters Halls of Fame; as of 2013, he is the only person ever inducted into all five.

Given its largely rural population during this period, Arkansas had no shortage of native musicians who decided to pursue country music. In the early part of the postwar era, the trade publications referred to the music of rural America as “folk,” while the music industry used the “hillbilly” label. Either moniker would have been embraced by Jimmy Driftwood of Timbo (Stone County), who used his grandfather’s homemade guitar in the process of penning literally thousands of songs over the course of his life. Driftwood’s chosen career was as a teacher, and after earning his degree in education from Arkansas State Teachers College (which later became the University of Central Arkansas), he began writing songs as a way to make learning more interesting for his students. Driftwood’s greatest success as a songwriter and musician came relatively late in life. He became a member of the Grand Ole Opry in the 1950s and was in his fifties when he charted six songs simultaneously on the pop and country charts in 1959. Five Driftwood songs would eventually earn Grammy Awards, including “The Battle of New Orleans”—a song written in 1936 as a lesson for his students—which was named Song of the Year in 1959.

Conway Twitty, born Harold Lloyd Jenkins, was one of the top country artists of the twentieth century. In 1943, when he was about ten, his family moved to Helena from Louisiana. He formed his own band, the Phillips County Ramblers, and, after serving in the military, went to Memphis to pursue his music career. It was here that he took his stage name by combining Conway (Faulkner County), Arkansas, and Twitty, Texas. By 1958, his rock and roll recording “It’s Only Make Believe” was number one. But even with his success as a rock and roll performer, Twitty preferred country music. By 1965, he had changed genres. His 1968 recording “Next in Line” became his first country number-one single. Twitty released dozens of top-rated singles in his rock and country careers, recording some 110 albums. In the 1970s, Twitty and fellow country star Loretta Lynn collaborated on a number of highly successful duet recordings. He was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1999.

Future country legend Glen Campbell of Billstown (Pike County) hailed from southwestern Arkansas, meaning that a migration to Memphis and then Nashville was less natural. He picked up the guitar as a youth, and, in the mid-1950s, moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, to play in a band with his uncle; he later formed his own band. While honing his skills, Campbell became friends with fellow Arkansas expatriate and guitarist Louie Shelton of Little Rock, and then moved to Hollywood, California, in 1960 to work as a session musician. Campbell was quickly recognized as a formidable guitar player and found plenty of work (along with Shelton) as part of the renowned Wrecking Crew group of studio players. During this period, he played on records for a varied list of artists that included Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley, Merle Haggard, Jan and Dean, and Nat King Cole. For a time, he was also a key component of producer Phil Spector’s famed Wall of Sound. Campbell’s session work was also heard on the Beach Boys’ landmark Pet Sounds album, and, for a period in the mid-1960s, Campbell was a touring member of the Beach Boys, filling in for Brian Wilson, who had tired of the road.

Campbell also worked to launch his own solo career and struck gold in 1967 with “Gentle on My Mind” and “By the Time I Get to Phoenix”—performances that earned him five of his nine Grammy Awards. Eventually, Campbell’s listener-friendly brand of country pop topped the charts nine times on the way to his 2005 induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame.

Campbell is just a single example of an influential musical artist from Arkansas for whom the lines between country and rock were blurred. This was also the case with Levon Helm of Elaine (Phillips County), who picked up the guitar at an early age and performed in talent shows around Helena with his sister. What he described as the “hambone” elements of their act may have played a role in Helm’s fascination with the drums. It was the drumming that led to his hiring on as a teenager with rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins of Huntsville (Madison County), known for his wild stage antics. It was through Hawkins and his connections north of the border in Canada that Helm would meet the members of the group of multi-instrumentalists and singers that eventually became known simply as the Band. Often credited as being the progenitors of the Americana genre, the Band was adored by fans and critics alike, and Helm became one of the most respected drummers of the era. The Band’s active period with its original lineup began in 1967 and ended less than a decade later amid differences in creative vision between Helm and singer/guitarist Robbie Robertson. Their final concert in their original configuration was chronicled in the acclaimed Martin Scorsese documentary The Last Waltz—a project that Helm never truly embraced due to creative and logistical conflicts, again, with Robertson. The remaining members of the group reunited in 1983, releasing several studio albums, touring intermittently, and playing at their induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994—all without Robertson. The Band called it quits for good in 1999 following the death of Helm’s dear friend—bass player and singer Rick Danko. Helm was already battling throat cancer by this time, which severely marred his distinctive singing voice. He played several years with his own band, leaving the vocal duties to others, including his daughter Amy Helm. By 2004, he was singing again and later released two studio albums and one live album, all of which won Grammy Awards. Helm died of cancer in 2012.

Straightforward, “Southern fried” rock and roll was the style of Black Oak Arkansas (BOA), led by the flamboyant front man “Jim Dandy” Mangrum of Black Oak (Craighead County). His onstage mannerisms and vocal trademarks were unabashedly copied by David Lee Roth of the more successful Van Halen (with Mangrum’s evident but unsolicited approval). All of the members of BOA originally hailed from Craighead County but spent some time based in New Orleans, Louisiana, and Memphis, where they signed with the mostly R&B-oriented Stax Records as the Knowbody Else. The band finally signed with Atlantic subsidiary Atco and settled at a compound in the Ozark Mountains, where many of their antics were chronicled by manager and future central Arkansas concert promoter Butch Stone. BOA was prolific, releasing fourteen live and studio records between 1971 and 1978. The band’s popularity had peaked by that time, as the record-buying public became more enamored of the disco and “urban cowboy” fads. Still, BOA continued to release albums despite frequent personnel changes, even involving Mangrum. As of 2013, the group was still playing occasional concerts as Jim Dandy’s Black Oak Arkansas.

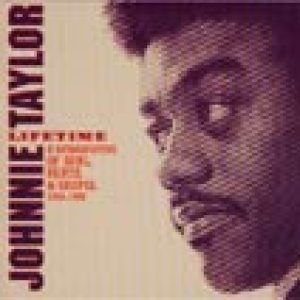

The disco craze would prove to be the high point in the already distinguished career of Johnnie Taylor of Crawfordsville (Crittenden County). Even though he was well established as a respected blues, soul, gospel, and R&B singer and one of the biggest artists charting hits for Stax, Taylor was perhaps best known for his 1976 hit “Disco Lady,” which spent four weeks at the top of the pop chart and was the first single ever certified platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America for sales of two million copies. Much of Taylor’s tenure at Stax was spent while the label was being run by Al Bell of Brinkley, who made Taylor a marquee artist at the label along with icons like Isaac Hayes and the Staple Singers. Bell is the writer of “I’ll Take You There,” arguably the Staples’ signature song.

The R&B talent from Arkansas was prodigious. “Little Willie” John of Cullendale (Ouachita County) had a short but extraordinary career as an R&B artist. He was the first to cut the song “Fever,” which went on to be recorded numerous times by Peggy Lee, Barry Gibb, and Madonna, to name a few. The John recording, produced by Henry Glover of Hot Springs (who was also a trusted friend of Levon Helm throughout his career) hit the top of the R&B chart in 1956. John’s personal demons caused his star to fade, and he charted his last hit in 1961. He died in prison in 1968, but the significance of his contributions did not go unrecognized; he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996.

Al Green of Forrest City (St. Francis County) was one of the world’s brightest musical stars in the early 1970s when he released a string of number-one albums, until a domestic incident with a girlfriend at his Memphis home pushed him into the ministry. While preaching, Green found middling success exclusively as a gospel singer but gravitated back to R&B in the late 1980s and went on to release a number of secular albums that did well but never achieved the success he enjoyed at the peak of his career.

The blues continued to thrive in Arkansas in the post-war years in the hands of such musicians as Williamson, Lockwood, and Nighthawk. It was with the latter that a young Frank “Son” Seals of Osceola got his start as a drummer. He soon picked up the guitar and began tearing up the Chicago blues scene. His contemporary, Luther Allison of Widener (St. Francis County), taught himself to play guitar and went on to share the stage with the likes of Howlin’ Wolf and Freddie King.

Jazz, Opera, and Classical Music in the Modern Era

Arkansas is not commonly associated with jazz, opera, or classical music even though recognition is warranted. Pharoah Sanders, born in Little Rock, worked as a sideman for John Coltrane and Don Cherry before setting out on his own. He became one of the most admired saxophone players in jazz, moving from avant-garde to hard bop and post-bop. He became a free jazz pioneer, eventually influencing his former mentor, Coltrane, with his dissonant style. Sanders earned a Grammy Award in 1988 for his part in a collaborative tribute to Coltrane.

Cool jazz and bebop pianist and singer Bob Dorough of Cherry Hill (Polk County) became an influential figure, first achieving success in the 1950s. His biggest influence may have been as the composer and singer for many of ABC’s Saturday morning Schoolhouse Rock! cartoons produced in the 1970s and 1980s.

Singer and actress Gretha Boston of Crossett (Ashley County) is the first Arkansan to win a Tony Award. The mezzo-soprano was recognized in 1995 as the Best Featured Actress in a Musical for her role as Queenie in the Broadway revival of Show Boat.

Some of the most prominent names in American opera are among the alumni of Opera in the Ozarks at Inspiration Point, a training program and festival located on a mountainside overlooking the White River west of Eureka Springs (Carroll County).

Barbara Hendricks of Stephens (Ouachita County) is one of the biggest stars in opera, as well as a noted humanitarian. Known for her interpretations of French and Scandinavian composers over the usual German and Italian fare, the soprano won competitions in New York, Switzerland, and France—and all prior to her graduation from Juilliard and her Paris, France, recital debut in 1973. In 2001, Hendricks performed at the Nobel Peace Prize concert in Oslo, Norway. In 2006, she started her own record label.

Robert McFerrin of Marianna (Lee County) received international acclaim as a baritone opera singer and a music teacher—and for fathering a subsequent generation of musicians, including Grammy Award–winning pop vocalist Bobby McFerrin. He moved to New York City in 1948 and made his operatic debut the following year in Verdi’s Rigoletto. McFerrin also sang in the world premiere of Troubled Island at the City Center of Music and Drama in New York City in 1949.

Troubled Island happened to be one of more than 150 pieces written by William Grant Still, who grew up in Little Rock. In 1931, Still became the first Black composer to have his work performed by a major symphony orchestra in the United States, when the Rochester Philharmonic performed his Afro-American Symphony. The same symphony was performed by the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall in 1935. In 1936, Still became the first African American to conduct a major symphony orchestra when he directed the Los Angeles Philharmonic during a performance of his own work at the Hollywood Bowl. Still’s body of work transcended racial barriers, however, and he is widely regarded as one of the most important and influential American-born composers.

Arkansas State University (ASU) professor Michael Dougan noted in his book Arkansas Odyssey that Scott Joplin, born in Texas and raised in Texarkana (Miller County), was the first major musical figure to hail from Arkansas and the first African American to gain acclaim in American musical history. “Born in 1868 near the present site of Texarkana, he studied with his violinist father and played piano in honky-tonks and brothels,” wrote Dougan. “By the turn of the century, he had become the preeminent figure in an essentially Black musical idiom known as Ragtime of which he was the accomplished king. Joplin’s own piano playing was preserved on piano rolls, and he composed perhaps the first opera by a Black composer, Treemonisha. Set in Reconstruction Arkansas to libretto of his own devising, the opera celebrated the victory of education over superstition and ignorance.” The work is said to be influenced by both Joplin’s mother, Florence, and his second wife, Freddie, whom he married in her hometown of Little Rock just weeks before her death in 1904 from pneumonia at the age of twenty.

The prolific composer Francis McBeth, who lived most of his life in Arkadelphia (Clark County), was a native Texan who found his home in Arkansas when he accepted the position of band director at what is now Ouachita Baptist University (OBU) in 1957, where he would remain as a distinguished professor and resident composer until his retirement in 1996. McBeth served as conductor of the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra from 1971 to 1973 and is credited with making the ensemble a viable and financially stable entity with its own permanent venue and professional musicians. In 1975, McBeth was named composer laureate of Arkansas—the first composer laureate in the United States.

Late Twentieth Century and Looking Forward

The 1980s saw far less Arkansas music finding national attention; the careers of the postwar luminaries were either slumping or in permanent decline. Little Rock’s Ho-Hum flirted with mainstream rock and roll success, even seeing a song of theirs used in an episode of the popular television program Melrose Place. Little Rock band Ashtray Babyhead found some interest from major labels with its brand of hook-laden power-pop but ultimately never achieved success as a group even after re-branding themselves with the radio-friendly moniker the Kicks. Member Jeff Matika eventually joined Arkansas native Jason White of North Little Rock (Pulaski County) in the ranks of popular rock band Green Day as a touring member.

The future of Arkansas music remains bright, however. For example, Trout Fishing in America of Prairie Grove (Benton County) combined keen talent, hard work, and high-mileage vehicles in building a loyal audience stretching from coast to coast. Between 1979 and 2010, the duo, consisting of bassist Keith Grimwood and guitarist Ezra Idlet, released nearly two dozen albums—most on their own Trout Music label—as well as two books and at least two full-length concert videos. Almost half of the albums were marketed as “family” releases because of their kid-friendly content. As a result, many of the dates on their full touring schedule consist of daytime concerts for families, followed the same evening by more adult-oriented concerts in clubs. The band has been nominated for four Grammy Awards.

Multi-platinum-selling rock band Evanescence of Little Rock won Grammy Awards for Best New Artist and Best Hard Rock Performance in 2004 while being nominated for three others, including Album of the Year. The group, led by singer and multi-instrumentalist Amy Lee, is still producing music and touring as of 2013 despite numerous personnel changes.

Country singer Joe Nichols of Rogers (Benton County) signed his first record deal at age nineteen and, between 2003 and 2011, became a Music Row veteran with eight studio albums including a greatest hits compilation that included three number-one singles.

Shaffer Smith of Camden (Ouachita County), better known by his stage name Ne-Yo, is a singer/songwriter, producer, and actor known for collaborations with some of the biggest names in R&B and hip-hop music. By 2013, he had been nominated for more than a dozen Grammy Awards and had won three.

Memphis-based Americana and southern alt-country-rock band Lucero, fronted by Ben Nichols of Little Rock, was formed in 1998 and has released a number of acclaimed albums, including Nobody’s Darlings, which was produced by legendary pioneer of the “Memphis Sound” Jim Dickinson of Little Rock and released in 2005 on their own Liberty & Lament label, as well as 1372 Overton Park (2009), Women & Work (2012), and All a Man Should Do (2015).

A line can be drawn from Arkansas artists such as Louis Jordan and even comedian Rudy Ray Moore of Fort Smith to hip-hop and rap music. Jordan made copious use of the spoken word in his work, and his music is seen by many as a forerunner to rap and hip-hop. Later in his career, Moore appeared on records with pioneers of the genre, including Big Daddy Kane, Luther Campbell and 2 Live Crew, and Busta Rhymes. Arkansas’s own rap/hip-hop scene began bubbling under the surface in the 1980s and is active in the twenty-first century with a substantial number of prolific artists. No Arkansas rappers, however, have yet managed to gain the notoriety of their counterparts in other southern cities such as Memphis, New Orleans, and Houston, Texas.

The talent pool of Arkansas musicians is seemingly not as wide nor deep as it was during the postwar heyday, but the soil has been turned, and the influential seeds of the pantheon of Arkansas music are planted in fertile ground, leaving a rich legacy for those who will come after.

For additional information:

Arkansongs. https://www.ualrpublicradio.org/programs/arkansongs (accessed June 26, 2025).

Cochran, Robert. Our Own Sweet Sounds: A Celebration of Popular Music in Arkansas. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2005.

Dougan, Michael B. Arkansas Odyssey: The Saga of Arkansas from Prehistoric Times to the Present. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Co., 1995.

George-Warren, Holly, and Patricia Romanowski. The Rolling Stone Encyclopedia of Rock and Roll. New York: Rolling Stone Press, 2001.

Hansen, Gregory. “KASU FM 91.9’s ‘Bluegrass Monday’: Performing Intangible Cultural Heritage and Fostering Historic Preservation in Arkansas, USA.” In Sustaining Support for Intangible Cultural Heritage, edited by Shihan de Silva Jayasuriya, Mariana Pinto Leitão Pereira, and Gregory Hansen. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2022.

Harvey, Paul. Southern Religion in the World: Three Stories. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2019.

Kingsbury, Paul, ed. The Encyclopedia of Country Music. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Koch, Stephen. From Almeda to Zilphia: Arkansas Women Who Transformed American Popular Song. Little Rock: Et Alia Press, 2024.

Palmer, Robert. Deep Blues. New York: Penguin Books, 1982.

Welky, Ali, and Mike Keckhaver, eds. Encyclopedia of Arkansas Music. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2013.

Keith Merckx

Arkansongs

"I Won't Tell a Soul I Love You," Performed by Al Hibbler

"I Won't Tell a Soul I Love You," Performed by Al Hibbler  "Arkansas Traveler"

"Arkansas Traveler"  "Big Bill Blues," Performed by "Big Bill" Broonzy

"Big Bill Blues," Performed by "Big Bill" Broonzy  Gretha Boston

Gretha Boston  Brockwell Gospel Music School

Brockwell Gospel Music School  "Big Bill" Broonzy

"Big Bill" Broonzy  The Browns

The Browns  Albert E. Brumley

Albert E. Brumley  Roy Buchanan

Roy Buchanan  Sarah Caldwell

Sarah Caldwell  Johnny Cash

Johnny Cash  Earl Cate

Earl Cate  Floyd Cramer

Floyd Cramer  "Crépuscule," Performed by Barbara Hendricks

"Crépuscule," Performed by Barbara Hendricks  CeDell Davis

CeDell Davis  Iris DeMent

Iris DeMent  Diamond State Chorus

Diamond State Chorus  Jimmy Driftwood

Jimmy Driftwood  Evanescence

Evanescence  "Fattening Frogs for Snakes," Performed by "Sonny Boy" Williamson

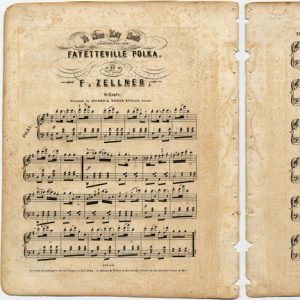

"Fattening Frogs for Snakes," Performed by "Sonny Boy" Williamson  "Fayetteville Polka" Sheet Music

"Fayetteville Polka" Sheet Music  Fiddle Player

Fiddle Player  Lonnie Glosson

Lonnie Glosson  Al Green

Al Green  Dale Hawkins

Dale Hawkins  Ronnie Hawkins

Ronnie Hawkins  Barbara Hendricks

Barbara Hendricks  Violet Hensley

Violet Hensley  Al Hibbler

Al Hibbler  Fred High

Fred High  "I Believe in You (You Believe in Me)," Performed by Johnnie Taylor

"I Believe in You (You Believe in Me)," Performed by Johnnie Taylor  "I Want to Be a Cowboy's Sweetheart," Performed by Patsy Montana

"I Want to Be a Cowboy's Sweetheart," Performed by Patsy Montana  "If You've Got the Money Honey (I've Got the Time)," Performed by Lefty Frizzell

"If You've Got the Money Honey (I've Got the Time)," Performed by Lefty Frizzell  "Jim Dandy," Performed by Black Oak Arkansas, Featuring Ruby Starr.

"Jim Dandy," Performed by Black Oak Arkansas, Featuring Ruby Starr.  Scott Joplin

Scott Joplin  Judsonia Army Band Performance

Judsonia Army Band Performance  Albert King

Albert King  "Kisses Sweeter Than Wine," Performed by the Weavers, Featuring Lee Hays

"Kisses Sweeter Than Wine," Performed by the Weavers, Featuring Lee Hays  Sleepy LaBeef

Sleepy LaBeef  "Last Date," Performed by Floyd Cramer

"Last Date," Performed by Floyd Cramer  Marjorie Lawrence

Marjorie Lawrence  Tracy Lawrence

Tracy Lawrence  Mary Lewis

Mary Lewis  Robert Lockwood Jr.

Robert Lockwood Jr.  "Luther's Blues," Performed by Luther Allison

"Luther's Blues," Performed by Luther Allison  Robert McFerrin Sr.

Robert McFerrin Sr.  "Moanin' at Midnight," Performed by "Howlin' Wolf"

"Moanin' at Midnight," Performed by "Howlin' Wolf"  "Moondog Monologue," Performed by Moondog

"Moondog Monologue," Performed by Moondog  Museum of the Arkansas Grand Prairie Exhibit

Museum of the Arkansas Grand Prairie Exhibit  Conlon Nancarrow

Conlon Nancarrow  K. T. Oslin

K. T. Oslin  Twila Paris

Twila Paris  "Peter Gunn," Performed by Roy Buchanan

"Peter Gunn," Performed by Roy Buchanan  Florence Price

Florence Price  Vance Randolph with Musicians

Vance Randolph with Musicians  Wayne Raney and Lonnie Glosson

Wayne Raney and Lonnie Glosson  "Red Headed Woman," Performed by Sonny Burgess

"Red Headed Woman," Performed by Sonny Burgess  "The Most Beautiful Girl in the World," Performed by Charlie Rich

"The Most Beautiful Girl in the World," Performed by Charlie Rich  Almeda Riddle

Almeda Riddle  "Rock Me," Performed by Sister Rosetta Tharpe

"Rock Me," Performed by Sister Rosetta Tharpe  Pharoah Sanders

Pharoah Sanders  "Your Love is Like a Cancer," Performed by Son Seals

"Your Love is Like a Cancer," Performed by Son Seals  Ruby Starr

Ruby Starr  William Grant Still

William Grant Still  There's a Star Spangled Banner Waving Somewhere

There's a Star Spangled Banner Waving Somewhere  Top of the Rock Chorus

Top of the Rock Chorus  Alphonso Trent Orchestra

Alphonso Trent Orchestra  Trout Fishing in America

Trout Fishing in America  Conway Twitty

Conway Twitty  T. Texas Tyler

T. Texas Tyler  William Warfield

William Warfield  Jimmy "Spoon" Witherspoon

Jimmy "Spoon" Witherspoon

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.