calsfoundation@cals.org

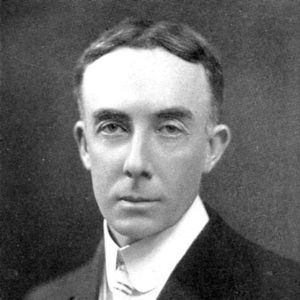

Hay Watson Smith (1868–1940)

Hay Watson Smith, a Little Rock (Pulaski County) Presbyterian minister, was a leading opponent of the movement to outlaw the teaching of biological evolution in Arkansas schools during the 1920s. His liberal viewpoints, both political and theological, brought him into conflict with traditional elements and resulted in charges of heresy by some within the southern Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS).

Hay Smith was born on February 18, 1868, the fifth of seven children, to J. Henry Smith and Mary Kelly Watson Smith in Greensboro, North Carolina. His father was a prominent Presbyterian minister. His brother, Henry Louis Smith, was later president of Davidson College in North Carolina, which Smith attended, graduating in 1890.

Smith then entered Union Theological Seminary in Virginia but did not stay long. Ill health and “doubts as to whether [he] had chosen the right profession” caused him to withdraw from Union. After teaching in the South Carolina schools for two years, Smith returned to Union in 1893 and graduated in 1897. He did postgraduate work at Union Theological Seminary in New York. In 1920, received a doctor of divinity degree from Oglethorpe University in Georgia.

In 1902, Smith married Jessie Alice Rose of Little Rock, daughter of the prominent lawyer Uriah M. Rose. They had five children.

The historical record is not clear as to why Smith decided to become a Presbyterian minister, for he was initially drawn to the avowedly liberal Congregational Church. Smith’s first ministerial appointment was as pastor at Parkdale Congregational Church in Brookline, New York. From 1906 to 1909, he pastored First Congregational Church in Port Chester, New York. Leaving Port Chester, Smith served for a year as president of the Selma Military Institute in Alabama in 1910.

In February 1911, Smith accepted a temporary appointment as a minister at Little Rock’s Second Presbyterian Church and was soon offered the position permanently. Applying to the Arkansas Presbytery for official credentials, he read a statement as to his acceptance of evolution, his inability to accept biblical inerrancy, and disagreements with parts of the Presbyterian Confession of Faith. He was accepted by the Presbytery with only one dissenting vote.

Smith was by all measures a success as pastor of Second Presbyterian. Membership grew dramatically from 200 to more than 965 by the time of his retirement, making it the largest Presbyterian church in Arkansas.

Remarkable success in the pulpit did not, however, insulate Smith from controversy. The southern Presbyterian Church had opposed Darwinian evolution since the 1880s, a stance that was reaffirmed in 1924. Smith opposed the denominational leadership, preaching two sermons in 1922 on the topic and concluding that evolution was indeed scientific truth but that it posed no threat to Christianity. He followed up by publishing his sermons, with the pamphlet being distributed widely. This soon brought on a petition of protest from the Ouachita Presbytery to the national Presbyterian General Assembly, but no actions were taken against him.

On January 13, 1927, in the aftermath of the “Scopes Monkey Trial,” state representative Astor L. Rotenberry of Pulaski County introduced a bill to prohibit the teaching in any state-funded educational institution of “the theory that mankind ascended or descended from a lower order of animals.” Smith preached a sermon the following Sunday attacking the proposed bill and calling Rotenberry and his colleagues “uninformed men, men ignorant of all the evidence on which evolution is based, legislating against the intelligence of the world.” For good measure, he also distributed a pamphlet on the widespread acceptance of evolution by eminent scientists—as well as former president Woodrow Wilson, a devout southern Presbyterian.

Smith was one of a small number of witnesses who testified against the bill before the House Committee on Education on January 28, 1927. When the state Senate later killed the bill, Benjamin M. Bogard, a Missionary Baptist preacher, and a coalition of conservative religious leaders immediately began a petition drive to refer the matter to a popular vote in the November 1928 general election in the form of a constitutional amendment. Smith joined the Committee Against Act No. 1, which included former governor Charles H. Brough, then president of Central Baptist College in Conway (Faulkner County), Arkansas Gazette editor John Netherland Heiskell, and a number of prominent educators. On November 6, 1928, Arkansas voters approved the proposed amendment by a vote of 108,991 to 63,406. Arkansas was the only state in the nation to outlaw the teaching of evolution by means of an initiated act.

During the campaign, Smith published a twenty-three-page pamphlet titled “Some Facts About Evolution,” which not only attacked the initiated act but also decried the actions of Presbyterian leaders in opposing evolution. He personally paid to distribute 3,000 copies of the pamphlet to Presbyterian clergymen throughout the South. This action aroused a predictable response from conservatives within the denomination.

The 1929 Presbyterian General Assembly, acting at the request of a Georgia presbytery, ordered the Arkansas Presbytery to investigate the orthodoxy of Smith’s faith. On November 12, 1929, the Arkansas Presbytery appointed a commission to investigate Smith. After a brief investigation, the commission decided that while Smith might not hold to all provisions of Presbyterian orthodoxy, he had stated his differences in 1912 when accepted into the Arkansas Presbytery. The commission concluded by a vote of five to two that Smith’s beliefs did not affect “the essential and necessary doctrines of the Church.” The Arkansas Presbytery as well as the overall Arkansas Synod approved the commission’s report, though not unanimously.

The action of the commission did not put an end to the conflict. In 1931, the General Assembly approved an appeal to consider the propriety of the commission report. Smith responded with a blistering sermon on June 28, 1931, in which he concluded that “the heresy of today is the orthodoxy of tomorrow.”

The controversy raged for another three years. The Arkansas Presbytery consistently supported Smith, and this support was accepted by the Arkansas Synod. Ultimately, in 1934, the General Assembly heard the case again and sustained the action of the presbytery and synod in refusing to place Smith on trial for heresy.

Having been in poor health for some time, Smith retired as pastor of Second Presbyterian on October 1, 1939. He died on January 20, 1940. Three days later, the Arkansas Gazette ran an editorial that eulogized Smith as having “the highest type of intellectual and moral courage….” Smith, the editorial concluded, “was no closet scholar. For him, to believe was to champion….”

For additional information:

Ledbetter, Calvin R., Jr. “The Antievolution Law: Church and State in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 38 (Winter 1979): 299–327.

Vinzant, Gene. “The Case of Hay Watson Smith: Evolution and Heresy in the Presbyterian Church.” Ozark Historical Review 30 (Spring 2001): 57–70.

Tom W. Dillard

University of Arkansas Libraries

Hay Watson Smith

Hay Watson Smith

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.