calsfoundation@cals.org

Mexican War

aka: U.S.-Mexican War

aka: Mexican-American War

The Mexican War was triggered by American expansionism and President James K. Polk’s desire to annex the Republic of Texas as a state. As a frontier state, Arkansas was called upon early to supply troops after war against Mexico had been declared on May 13, 1846. By war’s end, about 1,500 Arkansans had served, and Senator Ambrose Sevier of Arkansas had helped settle the peace.

With Texas’s victory over Mexican general Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna’s troops in 1836, the former Mexican territory became an independent republic. For a decade, U.S. leaders had seen Texas’s independence as a first step to it joining the United States, part of a broader American view of “Manifest Destiny.” Mexico, however, never recognized Texas’s independence. American annexation of Texas in 1845 and the stationing of U.S. troops under General Zachary Taylor near the Rio Grande River in 1846 triggered war between the two countries.

In April and May 1846, Mexican and U.S. armies clashed along the Rio Grande. While Taylor’s army won battles at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma, a small force under Major Jacob Brown, a former president of the Arkansas State Bank, held off a siege by Mexican forces at Fort Texas, across the river from Matamoros, Mexico. Brown was killed in the siege. Shortly after Taylor’s forces drove Mexican troops from the area, Fort Texas was renamed Fort Brown, and the town of Brownsville, Texas, in time grew up around it. Brown’s death fanned the flames of patriotism in Arkansas and coincided with President Polk’s call for volunteers.

In May 1846, Polk wrote Governor Thomas Drew seeking two groups of volunteers with enlistment for one year. Volunteers elected their immediate officers but, unlike state militias, were required to take orders from U.S. Army superiors. The first group, a battalion—five companies of men from Clarksville (Johnson County), Dover (Pope County), Fort Smith (Sebastian County), and Smithville (Lawrence County), totaling about 380 men—was sent to Indian Territory to keep peace and allow U.S. forces there to enter the war. This infantry battalion was under the command of Lieutenant Colonel William Gray.

The second group recruited was a mounted regiment, known today as cavalry. These 870 volunteers were bound for Mexico and were formed into ten companies—two from Pulaski County; one each from Crawford, Franklin, Independence, Johnson, Phillips, Pope, Sevier counties; and one company from both Saline and Hot Spring counties. The companies rendezvoused at Washington (Hempstead County) and, on July 4, 1846, elected regimental officers. Archibald Yell, the state’s only sitting U.S. congressman, was elected colonel. John Selden Roane, a former speaker of the House in the state legislature, was elected lieutenant colonel. Solon Borland, a prominent physician, was elected major.

The regiment was ordered to march to San Antonio, Texas, to receive arms and supplies. While at San Antonio, the troops were put under the command of General John Ellis Wool, a War of 1812 hero, whom the Arkansans nicknamed “Old Granny” for his strict discipline. Mingling with troops from around the nation, the Arkansans suffered the first waves of often deadly disease, with combinations of the measles, the common cold, water-borne diseases, and dehydration likely killing somewhere between 100 and 200 people.

Under Wool, the Arkansans and other regiments were ordered to Chihuahua to take control of that important Mexican trade center. The troops crossed the Rio Grande near modern-day Del Rio, Texas, on October 8, 1846, on a bridge designed by Captain Robert E. Lee. At about that time, Wool learned that General Taylor’s troops had taken Monterrey, Mexico, and that an armistice had put the war on hold for weeks. Wool’s troops continued their march into Mexico, traveling up to thirty-five miles per day in the desert. In December 1846, Wool’s Army of the Central made a brutal march of 115 miles in three days from Parras to Agua Nueva, a few miles south of Saltillo. Taylor stopped the Chihuahua expedition because he needed Wool’s men for reinforcements due to the threat of Santa Anna’s Mexican army to the south.

At Agua Nueva, small groups of mounted soldiers were sent on patrols. Some thirty-four Arkansans under Major Borland were captured on January 23, 1847, at Encarnacion due to the lack of guards at the rancho where they and their Kentucky counterparts slept. Also captured there was Kentucky lieutenant Thomas J. Churchill, later an Arkansas governor.

While at Agua Nueva, the occupying Americans were preyed upon by rancheros, who stole horses and gear and attacked lone soldiers. When one of the Arkansans, Private Samuel Colquitt, was dragged to death by rancheros, the Arkansas volunteers retaliated. Soldiers from Captain C. C. Danley’s Pulaski County company and the Sevier County company found the civilians believed to be guilty and shot between seventeen and thirty. Taylor was infuriated by the atrocity and threatened to send the two companies back to the Rio Grande to perform hard labor. Before he acted, Santa Anna’s forces arrived in the area, and those troops were needed.

On February 21, 1847, the Arkansas regiment was ordered to remove supplies from Agua Nueva ahead of Santa Anna’s approaching army. As the Mexican forces arrived in the area, the Arkansans burned the remaining supplies and fell back to Taylor’s position at Buena Vista to await battle.

The Mexican forces had totaled 21,000 men when leaving San Luis Potosi, but that number shrank to about 15,000 from desertion during the desert march. Taylor’s position at Buena Vista was a plateau about two miles long facing south with high mountains on his left and deep ravines on his right down to the Saltillo road. Taylor’s forces on February 22, 1847, were some 4,700 men, most of them untested volunteers like the Arkansas mounted regiment.

The Arkansans, whose numbers had dwindled to 479 due to disease, were divided into three forces based on training and weaponry. Captain Albert Pike’s well-trained squadron (two companies) was assigned to guard Saltillo on the first day of battle. On the plateau to the left, Colonel Yell’s mounted volunteers, about 200, were put alongside Kentucky mounted troops. On the mountainside to the left, Lieutenant Colonel Roane had some 200 dismounted Arkansans armed with rifles. It was there that Mexican infantry launched early attacks but made no headway.

On February 23, Pike’s squadron was attached to the U.S. dragoons (cavalry) and served as reinforcements around the battlefield. That morning, due to a mistaken call to retreat by an Indiana colonel, the left gave way, and Roane’s forces fled from the mountain. Roane rallied some soldiers, but many Arkansans ran to the safety of the rancho Buena Vista and others.

Later that morning, the Kentuckians and forces under Yell, about 400 combined, observed a force of about 2,000 Mexican lancers threatening a U.S. wagon train. In desperation, the Kentucky and Arkansas forces charged the lancers, splitting and dispersing them, but Yell and Captain Andrew Porter (Independence County) were killed.

Pike’s men saw some further action that day, but for the Arkansans, the worst of the fighting was over. It was not until the next morning that U.S. forces awoke to find Santa Anna’s army had retreated south. Arkansas casualties were eighteen killed and twenty-three wounded, with most of the dead buried on the battlefield.

The Arkansas Regiment, under the command of Colonel Roane, saw no more battles and returned to Arkansas in June 1847. The bodies of Yell and Porter were disinterred and among the few shipped back to Arkansas. Also disinterred and returned to American soil was the body of Arkansas native Erastus Burton Strong, a graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point who served in the U.S. Army until his death on September 8, 1847, at the Battle of Molino del Rey.

Late in 1846, the United States recruited ten regiments of regulars to launch a mission against Vera Cruz and inland to Mexico City. Captain Allen Wood of Carroll County raised a company of Arkansans for the Twelfth Infantry and joined the forces of General Winfield Scott in the summer of 1847. Wood’s Arkansans fought in the battles of Contreras and Churubusco on August 19 and 20, 1847, on the outskirts of Mexico City. In a matter of weeks, Mexico City fell to Scott’s forces. Shortly thereafter, the surviving Encarnacion prisoners were released.

One other company was recruited, that of Captain Stephen Enyart, whose northwestern Arkansas troops served at Meir, Mexico, guarding supply wagons.

Arkansas senator Ambrose Sevier played a prominent role in the negotiation of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Sevier shepherded the treaty through its U.S. Senate ratification, and Polk called upon Sevier to serve as a commissioner to guarantee its ratification in the Mexican congress. On June 12, 1848, Sevier left Mexico City with the last occupying U.S. troops, carrying the ratified treaty in his saddle bag.

There were ill feelings among some of the Arkansans due to their newspaper correspondence during the war, leading to a duel between Pike and Roane near Fort Smith in 1847, though neither was wounded. Pike had blamed Yell (and, by inference, Roane) for the poor training that led to many Arkansans running and some dying. Roane had (mistakenly) said in a newspaper account that Pike’s squadron did not fight in the battle at all.

The war helped the political careers of two Arkansans: Roane was elected governor in 1849, and Borland succeeded Sevier in the U.S. Senate. Roane and Pike became generals in the Confederacy, as did James F. Fagan, who had enlisted for Mexico as a private from Johnson County. Arkansas officers likely were acquainted, too, with later Confederate Civil War notables such as Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, and Braxton Bragg, dating to their service together under Wool and Taylor.

For additional information:

Allen, Desmond Walls. Arkansas’ Mexican War Soldiers. Conway, AR: Arkansas Research, 1988.

Bauer, K. Jack. The Mexican War, 1846–1848. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co. Inc., 1974.

Brown, Walter Lee. A Life of Albert Pike. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Buhoup, Jonathon H. Narrative of the Central Division or Army of Chihuahua, Commanded by Brigadier General Wool. Pittsburgh: M. P. Morse, 1847.

Chamberlain, Samuel E. My Confession. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1956.

Frazier, Donald S. The United States and Mexico at War. New York: Simon and Schuster Macmillan, 1998.

Frazier, William A., and Mark K. Christ, eds. Ready, Booted, and Spurred: Arkansas in the U.S.-Mexican War. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2009.

Fulton, Maurice Garland, ed. Diary & Letters of Josiah Gregg; Excursions in Mexico and California, 1840–1847. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1941.

———. Diary & Letters of Josiah Gregg; Excursions in Mexico and California, 1847–1850. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1944.

Hughes, William W. Archibald Yell. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1988.

Mexican-American War Collection. Old State House Museum Online Collections. Mexican-American War Collection (accessed August 10, 2023).

“Try Us: Arkansas and the U.S.-Mexican War.” Old State House Museum, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Bill Frazier

Memphis, Tennessee

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860 Military

Military Battle of Buena Vista Memorial

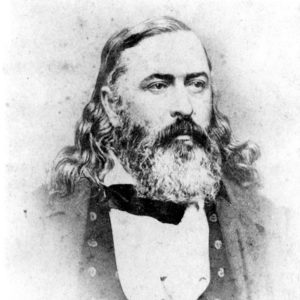

Battle of Buena Vista Memorial  Solon Borland

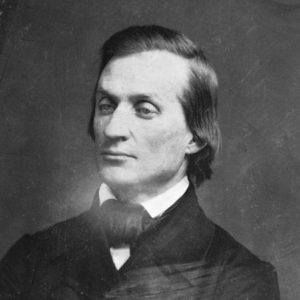

Solon Borland  Albert Pike

Albert Pike  Pike's Little Rock Guards Battle Flag

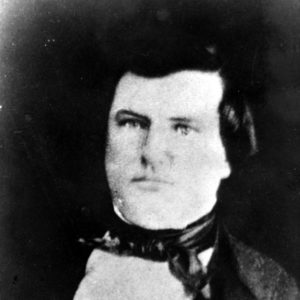

Pike's Little Rock Guards Battle Flag  John Roane

John Roane  Ambrose Sevier

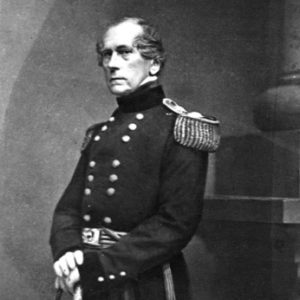

Ambrose Sevier  John Wool

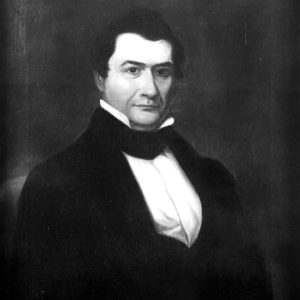

John Wool  Archibald Yell

Archibald Yell

This piece is a mix of good information on the ORGANIZATION of Yell’s Arkansas Mounted Infantry (thanks!) and a whitewash on that regiment’s horrible performance in Texas and northern Mexico in 1846 and 1847. Yell, Roane, and Borland, their own poor preparation, lack of discipline, and pride (or politics, alcoholism, and chivalry) were largely at fault, according to Zachary Taylor and most of the Army of Observation. Albert Pike, the disciplinarian whose squadron from the Arkansas regiment performed so well with May’s regular Dragoons at Buena Vista and throughout the campaign, and who constantly differed with Yell and his minions, gets little of the credit he deserves.