calsfoundation@cals.org

Blue Laws

Arkansas’s first blue laws, also called Sunday-closing laws, were enacted in 1837, only a year after Arkansas’s statehood. Though no blue laws have been in effect since 1982, they influenced the state’s culture and commerce for nearly a century and a half.

Blue laws have been part of American history since people began emigrating from Europe, where the laws were common. Virginia established the first blue law in the American colonies in 1610. The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution forbidding the establishment of religion may have called into question the legality of Sunday-closing laws, but it did not stop nearly all states from adopting them.

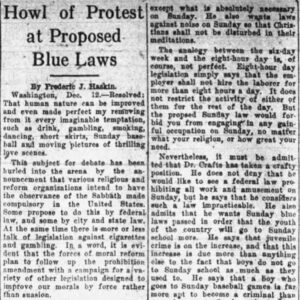

Historically, courts have ruled that state legislatures could proclaim a weekly day of rest for laborers for the promotion of the public welfare, and that it was appropriate for that day to be the one preferred by the majority of the state’s citizens. In 1961, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, in McGowan v. Maryland, that state legislatures could enact blue laws so long as they had a secular purpose and would not advance any particular faith. A legislature could make such regulations in pursuit of the health, safety, and welfare of the public.

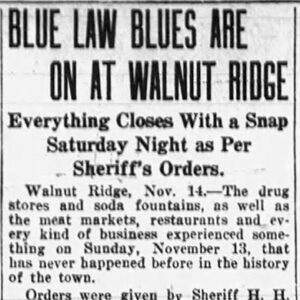

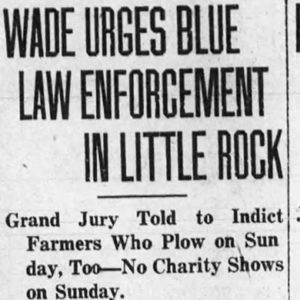

Arkansas’s first blue law “prohibited not only all sales on Sunday, but also all labor on Sunday with some minor exceptions for acts of daily necessity and charity.” However, a person who wasn’t a Christian could open a store on Sunday if he closed it on another day of the week. Legislative revisions in the 1850s added prohibitions against card games, hunting, horse racing, and baseball on Sunday. Although some gradually were done away with, much of the statewide blue laws remained on the books until they were repealed in 1957. After the U.S. Supreme Court ruling of 1961, the Arkansas General Assembly again adopted Sunday-closing laws in Act 135 of 1965, which specified that the purpose of the act was to provide for a uniform day of rest. It prohibited the sales of many commodities, ranging from clothing, house wares, and building materials to radios and televisions.

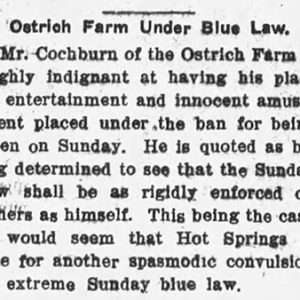

During the 1960s and 1970s, and throughout the period until the act was struck down in 1982, the Arkansas Gazette and other newspapers argued on their editorial pages against the state blue laws and local ordinances that allowed the arbitrary sale of items such as fishing hooks but not light bulbs; in some instances, one could buy film but not cameras. Prohibited items were covered by cloth or restricted by signs. Richard Allin, the late Gazette columnist, often ridiculed silly blue laws.

Act 135 was struck down by the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1982 in the case of Handy Dan Improvement Center Inc. v. Charles G. Adams on the issue that it was constitutionally vague. The bottom line was that the blue laws were not enforced equitably, and that lack of parity led to unfair competition, causing some to prosper and others to suffer. After the ruling, an editorial in the Arkansas Gazette commented thusly: “Let the free market govern. The hours of opening and closing on Sunday or any other day should be set by decisions made in the marketplace, not in the legislature.”

Arkansas Code, however, allows the city council or board of directors of any city to have the authority to create ordinances that regulate the operation of businesses within such cities on Sundays, which some still do, particularly in the area of liquor sales.

Two socio-economic factors have been credited for bringing an end to most of the laws and making Sunday the second-busiest shopping day of the week—the labor movement and women entering the workforce. Although the state legislature is free to adopt blue laws again, Arkansas currently has no state blue law. Local communities are free to pass their own blue laws, but much of what remains is simply tradition. Many stores, for instance, voluntarily will not open on Sunday until after noon to allow their employees time to attend church or rest.

The state still maintains separate laws that control the sale of alcoholic beverages on Sunday as well as throughout the week, though many have been loosened. Although they might be labeled “kissing cousins” to blue laws that regulated commerce, alcohol laws are regulated by a commission that establishes its own regulations apart from the blue laws.

In July 2018, the city of Fort Smith (Sebastian County) repealed a 1953 ordinance that prohibited a person or business from operating a dance hall or other establishment that allowed dancing on Sundays. Police records showed that no one had been charged with Sunday dancing in Fort Smith for the previous twenty years, illustrating some blue laws may remain on the books long after active enforcement has ceased.

For additional information:

Hartley, Jillian. “Arkansas Sunday Laws in the Nineteenth Century.” MA thesis, Arkansas State University, 2001.

Henry, John. “Sunday Has Become a Day of Business-As-Usual.” Arkansas Business, October 29–November 4, 2001, pp. 23–24.

Hughes, Dave. “City Dumping Outdated Laws, Panels.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, July 16, 2018, pp. 1B, 6B.

Kennon, Charles L., III. “Constitutional Law-Due Process-Arkansas’ Sunday Closing Law is Declared Unconstitutionally Vague.” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Journal 6.2 (1983): 305–319.

John Henry

White Hall, Arkansas

Havis, Ferd

Havis, Ferd Blue Law Closings

Blue Law Closings  Blue Laws

Blue Laws  Blue Laws Article

Blue Laws Article  No Plowing Allowed

No Plowing Allowed

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.