calsfoundation@cals.org

Streetcar Segregation Act of 1903

The Streetcar Segregation Act, adopted by the Arkansas legislature in 1903, assigned African American and white passengers to “separate but equal” sections of streetcars. The act led to boycotts of streetcar service in three Arkansas cities.

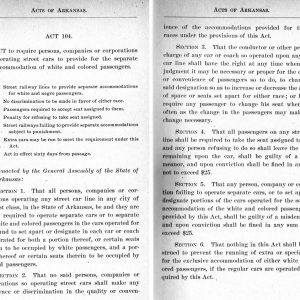

The Streetcar Segregation Act (Act 104), introduced by Representative Reid Gantt of Hot Springs (Garland County) and modeled after legislation in Virginia and Georgia, was a more moderate version of earlier segregationist legislation. The act did not require separate coaches for Black and white passengers but rather required segregated portions of streetcar coaches with separate but equal services.

On March 10, 1903, Black leaders assembled at the First Baptist Church in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and demanded the halt of legislative efforts aimed at segregating streetcars. Such protest meetings usually fell on deaf ears in the Arkansas General Assembly. No Black lawmakers remained in the legislature after post-Reconstruction disfranchisement. However, boycotts were organized to carry the protest of such meetings to the streetcar companies themselves.

Jeff Davis, elected governor in 1900 while politicking the continuance of Jim Crow–era racial segregation, approved Act 104 on March 27, 1903. After this approval, Black leaders encouraged the economic boycott of the streetcars in Little Rock, Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), and Hot Springs.

The first day of the law’s enforcement was May 27, 1903, and boycotts in the three cities began. The May 28, 1903, Arkansas Gazette explains the boycott in Little Rock: “The Negroes have organized a ‘We Walk’ league of which the porter at a Fifth Street saloon is president, and at a recent meeting there is said to have been a resolution adopted providing that any member found riding on a street car should be fined a stated sum, each ride to constitute a separate offense.” The boycott endured until at least June 17, 1903. On this date, Black citizens exiting Wiley Jones Park in Pine Bluff “paid no attention” to “a number of cars [that] were banked to carry them away.”

Black patronage on the streetcars dropped in Little Rock, Pine Bluff, and Hot Springs by as much as ninety percent. J. A. Trawick, general manager of a Little Rock streetcar line, defended his company by saying, “Not more than 10 percent of our regular Negro patrons are riding….They can gain nothing by such a course, for the streetcar company can do nothing to change the law which has been enacted by the legislature.” The May 29 Arkansas Gazette states: “A streetcar official stated last night that there was no perceptible falling off in the receipts for the first day on which the law was effective. It was thought that the receipts would show a slight decrease on account of the boycotts of the negroes.”

While Black passengers boycotted the streetcar lines to protest the law, white passengers also vented their frustration with it. In fact, Trawick announced, “all the trouble we have had was from whites.” Many white people were angered when the law required them to move out of streetcar sections reserved for Black passengers. City police were responsible for enforcing the law. An Arkansas Democrat editorial criticized the law for its “impracticability.”

The boycott lasted several weeks. Even with the decline in use of streetcars in the mid-twentieth century, Jim Crow laws defined public transit in Arkansas’s urban centers for another six decades.

For additional information:

Gordon, Fon Louise. Caste and Class: The Black Experience in Arkansas, 1880–1920. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995.

Graves, John William. Town and Country: Race Relations in an Urban-Rural Context, Arkansas, 1865–1905. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

Jamie Metrailer

Central Arkansas Library System

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Transportation

Transportation Streetcar Segregation Act of 1903

Streetcar Segregation Act of 1903

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.