calsfoundation@cals.org

Harry Lewis Miller (1870–1943)

Harry Lewis Miller was a photographer active in Arkansas at the turn of the twentieth century. His White River landscapes and scenes of daily life throughout the north-central region of the state form an important aesthetic and social history legacy. While some of Miller’s images were familiar, they were generally unattributed until staff at the Museum of Discovery in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and Old Independence Regional Museum in Batesville (Independence County) researched his work and mounted exhibits in 1998 and 2003, respectively.

The oldest of nine children, Harry Miller was born on April 1, 1870, in Dodge County, Minnesota, to Anton and Mary (Lewis) Miller, who were farmers. By 1880, they had moved their growing family to North Dakota, near Fargo. Neither family stories nor Upper Midwest research has uncovered the sources of Miller’s photographic training. Many photographers of the time learned their craft through apprenticeships, as well as from magazines and books such as Octave Thanet’s An Adventure in Photography (1893).

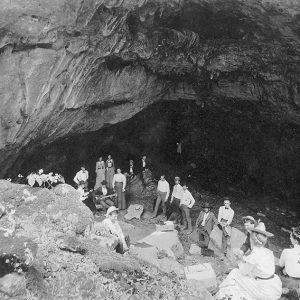

The 1900 Census lists Miller in Batesville boarding at a downtown Main Street address and operating a photographic studio a few blocks away. Surviving images—portraits, public event photos, postcards, and railroad souvenir booklets—document an active photographic practice. In his spare time, he roamed the White River country recording scenic views and images of people collecting mussels or picking cotton, and white and black residents at all sorts of daily activities from picnicking to drawing water. Miller arranged these pictures in personal albums, three of which survive. The majority of his photographs were made using a view camera and glass plate negatives, though there is evidence that he used the new roll film technology as well. Miller’s work is uniformly distinguished by a general excellence in execution, attention to formal composition, and by the amount of social information the images contain.

Miller married a young Batesville widow, Birdie Kennard McDearmon, on January 16, 1902. Their only known child, a boy named Kennard, died during the first year of their marriage.

Approximately 150 original Miller photographs are known to exist. Most are found in the personal albums created and arranged by him, now held by Old Independence Regional Museum, and in glass plate negatives held at the Museum of Discovery. Old Independence also holds photographs from his Batesville studio and examples of commercial souvenir work he produced. Additional images appeared in the Arkansas Sketch Book, a fine arts quarterly published by cultural entrepreneur Bernie Babcock. Several Arkansas repositories hold copies of Miller photographs.

Miller’s images are among the few depicting the actual landscape of the White River country and the Delta at the turn of the twentieth century. Miller made documentary images of the construction of both the locks and dams on the White River and the Missouri Pacific Railroad line built alongside the river in 1902–1905. He created a visual record of African Americans in north-central Arkansas, photographing children in particular, at chores and at play. Miller made dozens of images of everyday people going about daily activities. Though clearly stylized for artistic purposes, these images are also an informative record of small town and rural life circa 1900. Miller was especially skilled at capturing both overview and detail in his pictures. For example, in a cotton-picking scene, he shows the field, the workers, the overseers, and the background farmstead layout (quite unusual); he captures the coffer dam and entire stretch of river in a lock-and-dam construction image. Details of facial expression, clothing, and conveyance (ferries, wagons, and so on) are characteristically shown in both group and individual images. While many of the Miller photographs published in Arkansas Sketch Book and later in Babcock’s Little Rock Board of Commerce publication Yesterday and Today in Arkansas (1917) were captioned with phrases that perpetuated racial and hillbilly stereotypes, the photographer did not use similar phrases in his albums.

By 1910, the Millers had relocated to Little Rock (Pulaski County), renting an apartment and establishing a photographic studio in the capital city. Shortly afterward, they left Arkansas for the Upper Midwest and Canada, where he continued his photographic career. His activities between 1911 and 1920 are unknown. The Millers moved from North Dakota to Los Angeles, California, in the 1920s, participants in a large national migration. Miller did not work as a photographer in California. His initial employment was as a salesman for a diamond distributor, later as a dealer in secondhand goods. His wife took in fine sewing. According to grandniece and family researcher Marilyn Brewer, his nieces and nephews remembered Miller as a somewhat frightening person who drank heavily.

Miller died on January 14, 1943, at age seventy-two. He is buried in Rosedale Cemetery in Los Angeles.

For additional information:

“Batesville, 1904: Photographs Recall a Lively Time.” Arkansas Gazette. January 17, 1954, p. 2F.

Blatti, Jo, ed. Harry Miller’s Vision of Arkansas, 1900–1910. Batesville, AR: Old Independence Regional Museum, 2003.

Harry Miller Photograph Series, AR 2577. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Harry Miller Photographs in the Ottman, Edmundson, Brewer, Independence County Historical Society, and Blatti collections. Old Independence Regional Museum, Batesville, Arkansas.

Hewitt, Vonnie. “Batesville People Curious about Mysterious H. L.” Arkansas Gazette. October 16, 1980, p. 1D.

Miller Collection. Museum of Discovery, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Jo Blatti

Batesville, Arkansas

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Harry Miller Photo

Harry Miller Photo

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.