calsfoundation@cals.org

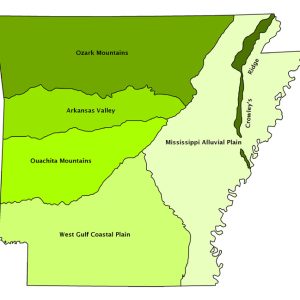

Arkansas Valley

aka: Arkansas River Valley

The Arkansas Valley, one of the six natural divisions of Arkansas, lies between the Ozark Mountains to the north and the Ouachita Mountains to the south. It generally parallels the Arkansas River (and Interstate 40) for most of its length. Its largest city is Fort Smith (Sebastian County), but many other cities are located there, including Van Buren (Crawford County), Alma (Crawford County), Ozark (Franklin County), Booneville (Logan County), Clarksville (Johnson County), Russellville (Pope County), Dardanelle (Yell County), and Morrilton (Conway County). Conway (Faulkner County), Heber Springs (Cleburne County), and Searcy (White County) are located near its boundary.

The Arkansas Valley is up to forty miles wide and includes geological features typical of both the Ozarks and the Ouachitas, including dissected plateaus like those of the Ozarks and folded ridges like those of the Ouachitas. However, some features are characteristic of the Arkansas Valley itself, including isolated, flat-topped, steep-sided mesas like Petit Jean Mountain, Mount Nebo, and Mount Magazine. Even though it is within a valley, Mount Magazine is the highest point in Arkansas at over 2,753 feet, and also by some definitions it is the only “mountain” in the state, since it is more than 2,000 feet from its base to its summit.

Precipitation declines noticeably along the length of the valley from east to west. The eastern end of the valley experiences the fifty to fifty-two inches of rainfall per year that is considered typical for Arkansas. However, the western end of the valley near the Oklahoma state line receives only about forty-one inches per year. The western Arkansas Valley lies in the rainshadow of the tallest mountains of the Ouachitas, and that end of the valley is open to the dry western winds from Oklahoma. This combination results in a significant drop in precipitation. The natural vegetation of the valley responds to this precipitation gradient by changing from forest at the eastern end to open woodland, savanna, and prairie at the western end.

The Arkansas Valley was originally formed by downwarping of a broad area as the Ouachitas were pushed northward and warped upward by continental collision toward the south. However, the Arkansas River and its tributaries have given it a truly distinct character by eroding away thousands of feet of sediment and creating the isolated mountains surrounded by broad, rolling uplands that are typical today. The Arkansas River also formed wide bottomlands and flat terraces that contribute further to the distinctive character of the valley. In fact, the valley has often been termed the Arkansas River Valley with considerable justification.

Tributary streams of the Arkansas that cross the valley tend to have low gradients and substantial bottomlands, even though they may be upland, even “white water,” streams nearer their headwaters. Streams like the Mulberry, Illinois Bayou, and Big Piney, which are favorite canoeing streams in the Ozarks, flow more gently and take on a more lowland character as they cross the valley toward their mouths at the Arkansas.

The Arkansas River has not only played a major role in developing the physical form of the valley, but it also contributes importantly to its biological distinctiveness by serving as a migration corridor for birds in their annual north-south passage. As migrating birds intersect the northwest-to-southeast-trending course of the river, they sometimes alter their route to follow its course. Pelicans, ducks, geese, and swallows may be seen moving in groups or singly along the river during spring and fall migration periods. Holla Bend National Wildlife Refuge, east of Dardanelle, offers outstanding opportunities for observation of these movements. It is likely that in earlier times, bison and elk may have similarly used the valley as a travel corridor.

People also have used the Arkansas Valley as a travel corridor, since it offers a relatively easy route through this generally mountainous area. The number of cities along its corridor is evidence of the importance of the valley for settlement and urbanization. Today, most of the valley is developed for various human uses, with few large forested areas remaining, other than on the steeper mountainsides.

There are distinctive subdivisions of the Arkansas Valley that share the general characteristics of the natural division as a whole but differ from each other in sometimes subtle, but important, ways. North and east of the Arkansas River is the Arkansas Valley Hills subdivision, characterized by low hills eroded from ancient plateaus. This area is similar in many ways to the Ozark Mountains to the north, in that the hills are flat-topped and streams have cut valleys into dendritic (tree-branched) patterns. However, the hill tops are usually distinctly lower in the Arkansas Valley than in the Ozarks. A good example of this is along U.S. Highway 65 north of Bee Branch (Van Buren County), where the highway climbs a steep hill, which is actually an escarpment from the Arkansas Valley to the Boston Mountains, part of the Ozark Mountains. However, just to the east at Heber Springs, the Little Red River has dissected this boundary so intricately that it is impossible to tell where the Arkansas Valley ends and the Ozarks begin. The Little Red River adds scenic beauty to the area, and it furnished a good damsite for Greers Ferry Lake. Some maps extend the valley to the north in this area, almost to Batesville (Independence County). The Arkansas Valley Hills subdivision has been less affected by the Arkansas River than the rest of the valley and is the only part where some streams, like the Little Red River, are not tributaries to the Arkansas but instead flow eastward to the White River. The trout fishery of the Little Red River below the Greers Ferry Dam is the most significant outdoor recreational resource of the subdivision. Because the hills that are common in this subdivision are fairly rugged, it is more forested than is typical of the rest of the valley, and the towns are smaller. Other than Heber Springs, Searcy, and Clarksville, all of which are on the edge of this subdivision, the largest towns are Greenbrier (Faulkner County) and Dover (Pope County).

Along the Arkansas River and toward the south, the landscape of the Arkansas Valley is much different. There, the Arkansas and its tributaries have eroded the mountains to level plains, interspersed by high mountains. The mountains have been protected from being eroded away by highly erosion-resistant sandstone caps. Thousands of feet of more erodible sandstone and shale have been removed between the scattered mountains. This gently rolling topography was once covered by open forests, woodlands, or savannas, surrounding small to large prairies. Many of the mountains are flat-topped remnants of ancient plateaus that may have been continuous at one time with the Boston Plateau of the Ozarks to the north. Others are folded ridges, often covered with shortleaf pine forest and woodland like those of the Ouachitas to the south. Some of these ridges are isolated within the valley, like one in Yell and Pope counties that was cut through by the Arkansas, creating a formation known as Dardanelle Rock that, according to some sources, reminded early travelers of the Dardanelles Strait in the Aegean Sea off Turkey. However, other such ridges to the south merge imperceptibly with the similar ridges of the Ouachitas. This combination of hardwood-covered plateau remnants merging with the Ozarks and folded piney ridges blending with the Ouachitas has led some to describe the Arkansas Valley as transitional between the two mountain systems. However, the broad prairies and wooded plains that make up the bulk of the landscape give the Arkansas Valley, and particularly this subdivision, a distinct character. The broad bottomlands along the Arkansas River, sometimes more than ten miles wide, add to its distinctiveness.

The streams and rivers that flow through these Arkansas Valley plains reflect their character: they flow gently, are bordered by broad bottomlands, and are often muddy (clayey from the erosion of shale). The Petit Jean River is the largest river to flow entirely with the valley from its head to its mouth at the base of Petit Jean Mountain.

People found the Arkansas Valley to be a practical travel route and a hospitable environment to live in from the time it was populated by Native Americans, who had large villages in some areas such as Carden Bottom along the lower Petit Jean River in Yell County. Travelers in the early nineteenth century and earlier passed through, such as the military expedition under Major Stephen Long, which returned east in 1817 from exploring the eastern Rocky Mountains. They described the landscape and the residents of the valley, including the Cherokee, some of whom had relocated there and had farms and orchards (only later were others forced to travel the “Trail of Tears” through the valley). Major Long selected the site for Fort Smith, on the edge of a prairie overlooking the Arkansas River, where it could serve as an outpost on the far western frontier.

Thomas Nuttall traveled by boat up and then back down the river in 1819, soon after the creation of Arkansas Territory, and kept a journal that described the region at that time. He provided vivid descriptions of the prairies and wooded ridges in the vicinity of Fort Smith. Interestingly, he did a sketch of the mountain he called “Mt. Magazine,” named as he said by the French because of its resemblance to a barn (magazine in French). The sketch is obviously of the mountain known today as Mount Nebo. It is unresolved whether the name of the mountains changed later or whether he misidentified them.

American settlers soon cleared much of the prairies and plains for pasture and crop land and founded towns that prospered with the diverse economy of the region. The Butterfield Overland Mail Company traversed the length of the valley, and, today, a stage house survives as a museum in Pottsville (Pope County). Railroads and highways, including I-40, took advantage of the ease of passage through the valley. The Arkansas River itself has been developed as the McClellan-Kerr Arkansas River Navigation System. The numerous cities are growing, and the valley has significant potential for population growth and industrial development.

For additional information:

Benson, Maxine. From Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains: Major Stephen Long’s Expedition, 1819–1820. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing, 1991.

Foti, Thomas. The Natural Divisions of Arkansas, A Classroom Guide. Little Rock: Arkansas Ecology Center, 1978. Online at http://www.naturalheritage.com/Education/ecoregions-natural-divisions-of-arkansas (accessed April 4, 2022).

Foti, Thomas, and Gerald Hansen. Arkansas and the Land. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1992.

Nuttall, Thomas. A Journal of Travels into the Arkansas Territory during the Year 1819. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

Thomas Foti

Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission

Arkansas System of Natural Areas

Arkansas System of Natural Areas Fayetteville Shale

Fayetteville Shale Geography and Geology

Geography and Geology Mount Magazine State Park

Mount Magazine State Park Arkansas River Valley

Arkansas River Valley  Cedar Falls

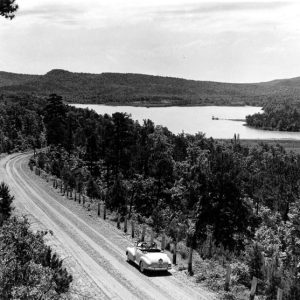

Cedar Falls  Cove Lake

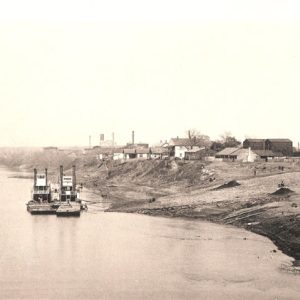

Cove Lake  Fort Smith; 1890s

Fort Smith; 1890s  Fort Smith Drawing

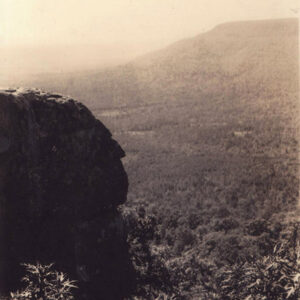

Fort Smith Drawing  Indian Head Rock

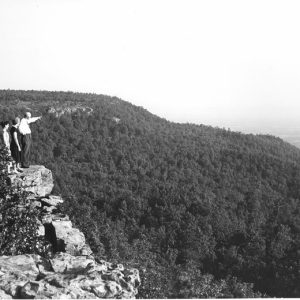

Indian Head Rock  Lake Dardanelle State Park

Lake Dardanelle State Park  Magazine Street Scene

Magazine Street Scene  Mount Nebo Hang Gliding

Mount Nebo Hang Gliding  Mount Nebo State Park

Mount Nebo State Park  Natural Divisions Map

Natural Divisions Map  Petit Jean State Park

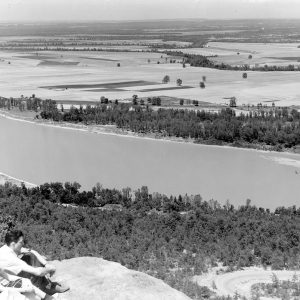

Petit Jean State Park  Petit Jean State Park View

Petit Jean State Park View  Petit Jean State Park

Petit Jean State Park  Petit Jean State Park

Petit Jean State Park  Springfield-Des Arc Bridge

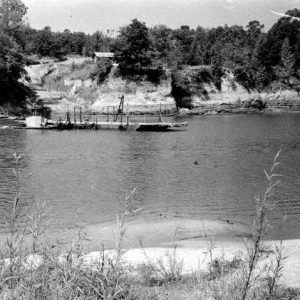

Springfield-Des Arc Bridge  Toad Suck Ferry

Toad Suck Ferry

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.