calsfoundation@cals.org

Lee Wilson & Company

Lee Wilson & Company, a diversified agribusiness headquartered in Wilson (Mississippi County), was founded by Robert E. Lee Wilson in 1885 and remained family owned and operated for approximately 125 years.

Robert E. Lee Wilson was born in 1865 in Mississippi County but moved with his mother to Memphis, Tennessee, at the age of seven after the sudden death of his father. He was orphaned at the age of thirteen when his mother died in a yellow fever epidemic; he was sent to live with an uncle. While attending school in Covington, Tennessee, he was introduced to land surveying and, through this, developed an eye for land. Wilson returned to Arkansas at the age of fifteen and worked as a wage laborer on a farm near Bassett (Mississippi County). He began farming the following year on land left to him by his father. Wilson realized the value in the hardwood forests that covered the Delta at that time and, after three years of farming, purchased a sawmill. In order to have timber for the mill, he traded a portion of his cleared land for 2,100 acres of timberland in Mississippi County. He continued farming as well, working more of the land that his father had left him.

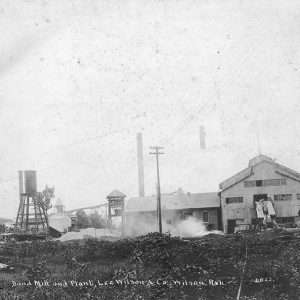

In 1885, Wilson and his new father-in-law went into business together, buying a sawmill at Golden Lake. By the following year, the business was incorporated as Lee Wilson & Company. As the partners cleared land farther away from the mill, they established logging camps, all of which were equipped with a company store, and towns quickly grew up around them. The Mississippi County towns included Marie and Victoria (named for two of Wilson’s family members), as well as Evadale, Keiser, and Wilson.

Unlike most timbering operations in the area that abandoned their cut-over land, Wilson cleared and drained his land and began growing cotton and, later, corn and alfalfa. Wilson also began building or buying railroads to lower the cost of exporting his goods and to aid in bringing people into the region. In addition to farming and railroads, he owned and operated banks, mercantile establishments in several towns, cotton gins, and a variety of manufacturing plants; for a while his company even produced and sold electricity.

Wilson’s record regarding labor relations is mixed. On the one hand, he treated his African-American laborers better than did many landowners in the Delta region, protecting them from abuse by managers within his company and by outsiders, including local law enforcement officials. On the other hand, employees were paid in scrip that was good only on the plantation, and property that they owned could not be removed from Wilson’s land. Those who chose to leave generally did so under the cover of darkness, relinquishing their homes and furnishings. The company was accused more than once of peonage—illegal hiring practices that held employees to their jobs against their will. In 1925, the Mexican consulate investigated charges that workers from Mexico had been promised wages of $1.50 an hour but were being paid sixty cents to a dollar an hour while being forbidden to leave. About the same time, Lee Wilson & Company was sued by an employee who claimed that he had been falsely accused of stealing from the company and then held in prison in Mississippi County until he agreed to work on the plantation picking cotton.

Wilson died in 1933, passing the company on to his son Robert E. Lee Wilson Jr. and a longtime employee, James Crain. The Wilson estate included more than 65,000 acres of farmland at that time. The company also operated most of the businesses and owned all of the houses in the town of Wilson, which the elder Wilson had created as a model town and which existed as a wholly owned subsidiary of the company. The company also owned and operated several businesses in five surrounding towns that had originally sprung up around his logging camps.

Wilson Jr. and Crain continued to operate the farming operation in a diversified manner, planting half of the land in cotton and the other half in corn and alfalfa that was primarily used to feed the thousands of mules used to pull the plows on Wilson land. They later added wheat to the crop mix.

Many changes occurred in the company after World War II. In the 1950s, the company passed into the hands of a new generation, with Robert E. Lee Wilson III taking command. The company town of Wilson, long operated by the business, began losing money. The company decided to sell the houses to their residents and incorporate the town, which would allow it to tap into badly needed tax dollars. The houses were sold at an average price of $4,000, and incorporation took place, although Wilson family members have always served as mayor. Lee Wilson & Company bought two agricultural implement dealerships, first Ford and then Case, and moved heavily into mechanization itself. A soybean oil facility was established, and the company entered the seed and agricultural chemical business.

After World War II, in an attempt to combat the labor shortage that occurred after thousands of Delta residents migrated to the urban areas, Lee Wilson & Company began importing Mexican nationals from the Bracero program to provide field labor. Each spring, the company would travel to processing facilities along the border, which were operated jointly by the United States and Mexican governments, pay a fee, and then bring the workers back for the season. Realizing an opportunity to move into other crops, especially with the amount of land allotted to row crops being reduced by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the company moved into vegetable production, growing and processing lettuce, spinach, cabbage, and other green vegetables, as well as sweet potatoes and strawberries. The company operated very successfully until the Bracero program was ended abruptly in 1964, at which point it could no longer find an adequate labor supply to maintain production.

Lee Wilson & Company subsequently returned to cotton production, adding rice and soybeans. The company continued processing seed oils and, for the first time, entered ranching. This diversification allowed the business to continue to prosper. The business continued into the twenty-first century with leadership in the hands of a fourth generation of Wilsons. At one time, the company employed thousands, but mechanization reduced the need for such a large amount of labor; the company at one point employed fewer than fifty people. In October 2010, it was announced that the Wilson family was selling the company; it was purchased in December 2010 by Gaylon Lawrence of Sikeston, Missouri, and his son, Gaylon Jr., of Nashville, Tennessee, for an estimated $150 million.

For additional information:

Lee Wilson & Company Archives. Arkansas Digital Library. http://libinfo.uark.edu/SpecialCollections/ardiglib/leewilson/default.asp (accessed February 14, 2022).

Lee Wilson and Company Collection. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas. Finding aid online at https://uark.as.atlas-sys.com/repositories/2/resources/1560 (accessed June 30, 2023).

Satterfield, Archie. Country Towns of Arkansas. Castine, ME: Country Roads Press, 1995.

Whayne, Jeannie. “The Changing Face of Sharecropping and Tenancy.” Historical Text Archive. http://www.historicaltextarchive.org/sections.php?action=read&artid=657 (accessed February 14, 2022).

———. Delta Empire: Lee Wilson and the Transformation of Agriculture in the New South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2011.

———. A New Plantation South: Land, Labor, and Federal Favor in Twentieth-Century Arkansas. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1996.

———. “Robert E. Lee Wilson and the Making of a Post Civil War Plantation System.” In The Southern Elite and Social Change: Essays in Honor of Willard B. Gatewood, Jr., edited by Randy Finley and Thomas DeBlack. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2002.

Woodruff, Nan Elizabeth. American Congo: The African American Freedom Struggle in the Delta. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003.

Cindy Grisham

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Staff of the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture

Lee Wilson & Co.

Lee Wilson & Co.  Lee Wilson & Company

Lee Wilson & Company  Lee Wilson & Company

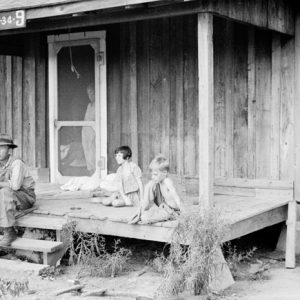

Lee Wilson & Company  Rickets Victim

Rickets Victim  Wilson Plantation Sharecroppers

Wilson Plantation Sharecroppers

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.