calsfoundation@cals.org

Mississippi Alluvial Plain

aka: Mississippi Delta

aka: Arkansas Delta

aka: Delta

aka: Mississippi River Delta

aka: Mississippi River Valley

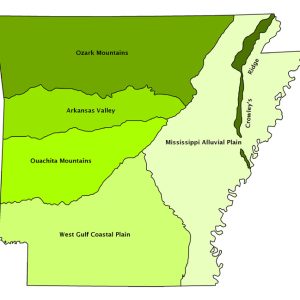

The Mississippi Alluvial Plain (a.k.a. Delta) is a distinctive natural region, in part because of its flat surface configuration and the dominance of physical features created by the flow of large streams. This unique physiography occupies much of eastern Arkansas including all or parts of twenty-seven counties. The Alluvial Plain, flatter than any other region in the state, has elevations ranging from 100 to 300 feet above sea level. In Arkansas, the Alluvial Plain extends some 250 miles in length from north to south and varies in width from east to west from only twelve miles in Desha County to as much as ninety-one miles measured from Little Rock (Pulaski County) to the Mississippi River.

The work of large rivers (including the Mississippi, Arkansas, White, and St. Francis rivers) and other smaller rivers and streams has played an important role in forming the character of the landscape. These rivers eroded older deposits and built up deep layers of soil, gravel, and clay transported from slopes as far away as the Rocky Mountains to the west and the Appalachians to the east. The result of these alluvial processes is a terrain and soil suitable for large-scale farming. In fact, the Mississippi Alluvial Plain is one of the most agriculturally productive regions in the world.

Alluvial (stream-deposited) material covers almost the entire region. Interestingly, terraces are found throughout the Alluvial Plain, frequently paralleling streams but at a slightly higher elevation than the adjacent stream banks. These terraces are older than present bottomlands and represent former levels of bottomland through which streams have now eroded. The so-called recent alluvium has been deposited over the last 12,000 years and contains fertile “water-washed” material, especially silt.

The deep, fertile soils of the Mississippi Alluvial Plain are sometimes extremely dense and poorly drained. The combination of flat terrain and poor drainage creates conditions suitable for wetlands. Wetlands, areas where the periodic or permanent presence of water controls the characteristics of the environment and associated plants and animals, now cover approximately eight percent of Arkansas’s land surface. While some wetland areas remain intact, many have been drained and converted to agricultural land uses. Protecting the remaining wetlands and encouraging the restoration of some former wetland areas are significant natural resource conservation issues.

At one time, wetlands were very abundant across the Mississippi Alluvial Plain. The decline in wetlands began years ago when the first ditches were dug to drain extensive areas of the Alluvial Plain. Clearing bottomland hardwoods for agriculture and other activities has resulted in the loss of more than seventy percent of the original wetlands.

The majority of Arkansas’s wetlands, occupying a diverse physiographic setting, are often riverine and depressional wetlands associated with the floodplains of the Mississippi River and its major tributaries. Some of the most significant wetlands are referred to as “bottoms” or “bottomland hardwood forests.” Of particular importance is the Cache River and lower White River area, where impressive stands of bottomland hardwoods are found. It represents the largest continuous expanse of bottomland hardwoods in the Lower Mississippi Valley. Nearly one-third of the remaining bottomland hardwoods in the Arkansas Delta are found within the ten-year floodplain of the Cache and lower White rivers.

The wetlands of the Delta offer an internationally important winter habitat for migratory water fowl. The White River National Wildlife Refuge alone is a temporary home to between 3,000 and 10,000 Canada geese and up to 300,000 ducks per year. These large numbers account for one-third of the total found in Arkansas and ten percent of the Mississippi Flyway total.

Wetlands of Arkansas serve many important functions in addition to being a vital wildlife habitat, including flood storage and flood prevention, natural water quality improvement (sediment traps, for example), shoreline erosion protection, groundwater recharge, recreational opportunities, and aesthetic beauty.

The original natural vegetation of the region was significantly different from the other natural regions in Arkansas in part because of the region’s wetland characteristics. It was largely southern floodplain forest suited to the wet, poorly drained soils. Cypress-tupelo-gum types occupied the wettest sites. The willow oak and overcup oak were found on flat and poorly drained locations, and oak-hickory on higher and better drained terrace sites of the floodplain.

Currently, the Mississippi Alluvial Plain has been widely cleared and drained for cultivation. The widespread loss or degradation of forest and wetland habitat has impacted wildlife and reduced bird populations. Relatively small plots of natural vegetation remain along streams, in areas unsuitable for agriculture, or within areas protected from clearing and development. The most significant of these protected areas are the Big Lake National Wildlife Refuge, the Sunken Lands Wildlife Management Areas, the Wapanocca National Wildlife Refuge, the St. Francis National Forest, and the White River National Wildlife Refuge.

A rather unique feature of this region is the Grand Prairie, an area of prairie soils and grasses that are found primarily in Arkansas and Prairie counties in eastern Arkansas. These prairie soils, with their very compact clay subsoil, are more suitable for grass than trees as the natural vegetation cover. The Grand Prairie is an extremely productive agricultural region and is noted for its high yields of rice. Stuttgart (Arkansas County) is known as the rice capital and duck capital of the world.

Another important characteristic of the Alluvial Plain is related to a significant natural hazard, earthquakes. These may occur along the New Madrid Seismic Zone. This seismic zone is a prolific source of intra-plate earthquakes (earthquakes within a tectonic plate) in the southern and mid-western United States. This seismic zone was responsible for the 1811–1812 New Madrid Earthquakes and has the potential to produce large earthquakes in the future. Several relatively small earthquakes have been recorded in the region since 1812, but an important question remains concerning the next “big” earthquake in terms of when it will occur and at what magnitude. As of 2011, according to some experts, there is a ten percent chance of a magnitude 7.0 quake within the next fifty years along the fault that extends from New Madrid, Missouri, to Marked Tree (Poinsett County) and beyond.

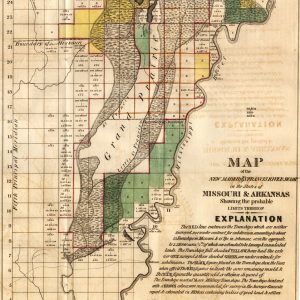

In addition to a unique physical landscape, the Mississippi Alluvial Plain has a number of distinctive cultural/demographic characteristics. In an article titled “Delta Population Trends: 1990–2000,” Jason Combs discusses the significant population decline that has occurred within counties bordering the Mississippi River. Population decline, economic depression, and other negative socioeconomic factors characterize many of these Delta counties. Data released from the 2010 census shows that the population decline is continuing within several Arkansas counties that are adjacent to or near the Mississippi River. The most significant population declines (between -10.1 and -20.5 percent) from 2000 to 2010 were in Mississippi, Lee, Phillips, Desha, Chicot, Monroe, and Woodruff counties. These counties have relatively high rates of unemployment and few or no positive features to reverse the trend of population decline, according to Combs.

These and other Delta counties have experienced population decline for a variety of reasons, in addition to high unemployment. According to Combs, part of the problem is the image of the Delta. Strained race relations, poverty, and resistance to social change have “tarnished” the Delta’s image and contributed to the absence of substantial economic development. Moreover, most Americans perceive the Delta as “flat and uninteresting, not a place to go for recreation, retirement, or a glamorous job,” according to an article by Richard Lonsdale and J. Clark Archer. Another contributing factor to the population loss in the Delta is agricultural mechanization. Improvement in mechanization and modern science allowed fewer farmers to produce as much or more agricultural output on the same amount of land with far less labor. The need for fewer farm workers coupled with the absence of other job opportunities has been a significant contributing factor to the population decline and the economic depression that many Delta counties are experiencing.

In summary, the Mississippi Alluvial Plain is a natural region with several distinguishing characteristics, including an extremely flat surface topography; deep alluvial soils; poor drainage; wetland areas; widely scattered bottomland and hardwood forests; large and highly productive farms; counties plagued by economic depression and population loss; and the Mississippi Flyway, with ideal locations for hunting, fishing, and other water-related sports activities. The result is a region marked by sharp social contrast: pockets of prosperity and wealth exist aside poverty and economic despair.

For additional information:

Arkansas Department of Planning. Arkansas Natural Area Planning. Little Rock: State of Arkansas, 1974.

Bryan, Colgan Hobson Jr. “Breaking the Poverty Cycle: An Investigation into the Correlates of Propensity for Change among the Rural Impoverished in the Mississippi Delta.” PhD diss., Louisiana State University, 1968. Online at https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1432/ (accessed May 18, 2022).

Collins, Janelle, ed. Defining the Delta: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on the Lower Mississippi River Delta. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2015.

Combs, Jason. “Delta Population Trends: 1990–2000.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 34 (April 2004): 26–35.

“Delta Is.” Delta Cultural Center. http://www.deltaculturalcenter.com/Learn/the-delta-is (accessed January 20, 2022).

Giggie, John M. After Redemption: Jim Crow and The Transformation of African American Religion in the Delta, 1875–1915. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Greene, Alison Collis. No Depression in Heaven: The Great Depression, the New Deal, and the Transformation of Religion in the Delta. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Hagge, Patrick David. “The Decline and Fall of a Cotton Empire: Economic and Land-Use Change in the Lower Mississippi River ‘Delta’ South, 1930–1970.” PhD diss., Pennsylvania State University, 2013.

———. “From Mule to John Deere: Elements of Rural Landscape Change in the Mississippi Delta, 1930–1970.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 49 (April 2018): 25–39.

Jolliffe, David A., Christian Z. Goering, Krista Jones Oldham, and James A. Anderson Jr. The Arkansas Delta Oral History Project. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2016.

Laurent, Brookshield, and Lauri Umansky, eds. “The Arkansisters Project: Self-Help Activism in the Delta through Grassroots Initiatives.” Special issue, Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 54 (December 2023).

Lonsdale, Richard, and J. Clark Archer. “Emptying Areas of the United States, 1990–1995.” Journal of Geography 97 (1998): 108–122.

Pierce, Michael, and Calvin White, eds. Race, Labor, and Violence in the Delta: Essays to Mark the Centennial of the Elaine Massacre. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2022.

Probasco, Susan E. “Delta Memories and Delta Days: Facets of Ladies’ Lives as Revealed to a Southern Daughter.” MA thesis, Louisiana State University, 2003. Online at https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2384/ (accessed June 13, 2022).

Richards, Eugene. Few Comforts or Surprises: The Arkansas Delta. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1973.

Schieffler, George David. “Civil War in the Delta: Environment, Race, and the 1863 Helena Campaign.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2017.

Simpson, Stephen. “Banker: Capacity Needed.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 28, 2021, pp. 1A, 7A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/dec/28/banker-capacity-needed/ (accessed January 20, 2022).

———. “Delta’s Cities Show Its Plight.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 27, 2021, pp. 1A, 4A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/dec/27/deltas-cities-show-its-plight/ (accessed January 20, 2022).

———. “Depression Poses Major Health Risk.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 27, 2021, p. 4A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/dec/27/depression-poses-major-health-risk/ (accessed January 20, 2022).

———. “State’s West Is a World Apart.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 26, 2021, pp. 1A, 6A, 7A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/dec/26/states-west-is-a-world-apart/ (accessed January 20, 2022).

———. “Towns in Delta Losing People, Hope for Change.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 26, 2021, p. 7A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/dec/26/towns-in-delta-losing-people-hope-for-change/ (accessed January 20, 2022).

———. “With Covid, Government’s Role in Delta Clearer.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, December 28, 2021, pp. 1A, 6A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/dec/28/with-covid-governments-role-in-delta-clearer/ (accessed January 20, 2022).

Stone, Jayme Millsap. “‘They Were Her Daughters’: Women and Grassroots Organizing for Social Justice in the Arkansas Delta, 1870–1970.” PhD diss., University of Memphis, 2010. Online at https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/etd/130/ (accessed June 21, 2022).

Stroud, Hubert B., and Gerald T. Hanson. Arkansas Geography: The Physical Landscape and the Historical-Cultural Setting. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1981.

Whayne, Jeannie, and Willard B. Gatewood, eds. The Arkansas Delta: Land of Paradox. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1993.

Hubert B. Stroud

Arkansas State University

Arkansas System of Natural Areas

Arkansas System of Natural Areas Geography and Geology

Geography and Geology Military Farm Colonies (Arkansas Delta)

Military Farm Colonies (Arkansas Delta) Bayou Bartholomew

Bayou Bartholomew  Mississippi River

Mississippi River  Natural Divisions Map

Natural Divisions Map  New Madrid/St. Francis River Swamp

New Madrid/St. Francis River Swamp

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.