calsfoundation@cals.org

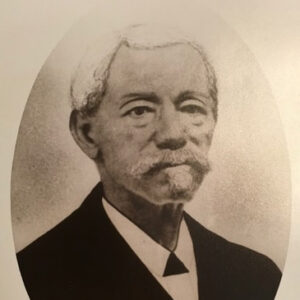

Nathan Warren (1812–1888)

Nathan Warren was one of the few free black businessmen in antebellum Arkansas, as well as a noted musician and the founder of the state’s first African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) congregation.

Nathan Warren was born into slavery in 1812 in Versailles, Kentucky, on the Crittenden Plantation. John Crittenden, brother of Robert Crittenden (and later Kentucky governor, U.S. congressman, and U.S. attorney general), was likely Warren’s father. Robert Crittenden brought Warren to Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1819, around the time Crittenden was appointed by President James Monroe as the first secretary of the Arkansas Territory. Crittenden and Warren lived at the present-day site of the Albert Pike Hotel on 7th Street, between Scott and Cumberland streets, in a large brick home that Crittenden built for himself and his wife.

Crittenden died in 1834 without a will and was declared to be insolvent. His wife was forced to sell her valuables, including her brick home. Daniel Greathouse bought Nathan Warren from her in 1835. Greathouse penned a note that would “grant Warren his freedom 3 years and 6 months after May 27, 1835.” Greathouse died in 1836. In 1837, Isaac C. Cooper went to court and testified that the manumission papers from Greathouse emancipating Nathan “Nase” Warren were authentic. The papers stated: “This is to certify that my yellow boy Nase is to be free after serving me three years and six months after the twenty seventh of May eighteen hundred and thirty five.” The court granted Nathan Warren his freedom, which came exactly one year later—and twenty months earlier than promised. After acquiring his freedom, Warren went to work as the personal carriage driver for Chester Ashley, a prominent attorney and wealthy landowner.

Nathan Warren began a close relationship with Ashley’s house slave Anne Lewis, the “quadroon” daughter of the Ashleys’ head cook, Rebecca or “Mammy Beck.” Before she married Warren, Anne Lewis already had a son, Bill Archy (W. A.) Rector, who was born in 1833 and fathered by a white man. Anne and Nathan were married around 1836; they had nine children. Warren continued to work for Ashley and lived at the Ashley Mansion, either in the “Big House” on Markham Street or in the slave quarters. Under the rules of Southern slavery, even though Warren was a free man, the children of Anne Warren remained slaves. Although Warren saved enough of his earnings to purchase his brother James Warren’s freedom later, Anne and her children were never freed.

In the 1840s, Warren opened a confection shop on Markham Street. The shop was first owned by Henry Jackson, another free black man. Warren took over the shop after Jackson invented a cooking stove and moved to Evansville, Indiana, to manufacture his invention. Warren became famous for his pastries, cookies, cakes, tea cakes, and other delicacies. He was known as “Little Rock’s Confectioner” and also catered weddings and other social events. His store was just down the street from the Ashley Mansion; a two-story business house, the store occupied a portion of the land on which the Capital Hotel was later built. Warren continued to work as Ashley’s carriage driver as well as serving as barber and general handyman. He was also an exceptional fiddler, and many of his children played in the Ashley Band, a string and brass band organized by Ashley.

Warren remained successful throughout the 1840s and the 1850s. He and his brother Henry Warren, also a free man, put their money together and bought their brother James Warren from Timothy Crittenden on July 9, 1844. Based on an Arkansas law passed in 1843, as well as a standing Little Rock city ordinance, no “free Negro” could enter the state of Arkansas as a resident, and those already in Arkansas had to post a $500 bond guaranteeing their good behavior and their self-support; therefore, when fourteen-year-old James Warren came to Little Rock to live with his brother, he arrived as a slave, co-owned by his free brothers.

On January 15, 1850, Nathan Warren purchased Henry Warren’s interest in their brother James for the sum of ten dollars. On February 5, 1850, Warren filed emancipation papers, thus freeing James “from servitude and confer[ing] upon him the rights and privileges of a free man.” According to the 1850 census, James was living in Nathan Warren’s household in Little Rock. It is assumed that James worked in Nathan’s confectionary and learned the trade from his brother.

Warren’s store caught fire just after midnight on March 19, 1852. The Arkansas Gazette reported that the fire was an accident, but Warren always believed it was arson. The fire was quickly extinguished before it could destroy the building or harm the nearby business houses, and Warren continued to operate his business from this location until the growing discontent about the presence of free blacks in Arkansas grew too strong.

Sometime after 1852, James Warren left Little Rock. Nathan Warren’s first wife, Anne, died around 1853, likely from complications following the birth of their daughter Ellen (Ella). A short time after Anne’s death, Warren married another one of Ashley’s slaves, Mary Elizabeth, a “quadroon.” On October 26, 1856, he bought Mary Elizabeth and their daughter, Ida May, from the widow of Chester Ashley.

In 1857, members of the Arkansas General Assembly tried to pass legislation expelling all free African Americans from the state but failed. Finally, the opposition to free blacks culminated in an act passed by the state legislature and approved on February 12, 1859, requiring all free blacks to leave the state—their only alternative being to become slaves. Consequently, Warren and his free family left Little Rock for Xenia, Ohio, while his enslaved children had to remain behind. During his time in Xenia, Nathan and Mary Elizabeth had at least five children living with them.

While living in Ohio, Warren became deeply involved in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and was ordained by Bishop H. M. Turner as a church elder, with all the rights and privileges of an AME pastor. Warren returned to Little Rock shortly after September 10, 1863, the date Little Rock fell to Union troops. Around November 1863, Warren founded Campbell Chapel AME Church in Little Rock in the home of Anthony and Lucy Elrod at 10th and Spring streets. The name was changed to Bethel AME Church, and Warren was the first pastor from its founding through 1868. Warren also composed spirituals, including one of his most famous, the “Resurrection Song.”

Following the end of the Civil War, Warren helped to organize and served as a delegate for the Convention of Colored Citizens of Little Rock, which was held between November 30 and December 2, 1865. As Little Rock’s premier fiddler at that time, he also played at major social events, weddings, and parties, for both black and white audiences.

On the night of January 31, 1866, the stern-wheeler steamship Miami, commanded by Captain E. A. Levy, running as a regular packet between Little Rock and Memphis, Tennessee, exploded and caught fire in the Arkansas River about six miles above Napoleon (Desha County). Over 200 lives were lost; among the dead were four members of the Ashley Band, including Warren’s sons George, Frank, John, and his daughter Maria’s husband, Wash Phillips. The only surviving members of the band were Nathan Warren’s son Isaiah and his stepson W. A. Rector, who escaped unharmed. The Ashley Band members who survived recruited other musicians, and after about six months, the band began performing again.

In 1868, Warren’s wife bought a one-and-a-half-story house at 1012 Ringo Street in Little Rock. (The house is still standing and occupied in the twenty-first century.) Warren was a successful businessman throughout his life, owning retail stores in different locations in downtown Little Rock. He was listed in the 1872 city directory as a baker at 110 West 5th Street. In 1873, he had a fruit stand in the next block west. In 1878, he worked in Francis Ditter’s Confectionery. In 1880, he owned a confectionery shop with W. C. Gibbons, called Gibbons and Warren, at 902 Main Street. By 1881, he was full owner of the shop.

On November 19, 1882, at Morrilton (Conway County), Warren was made an elder of the AME church.

Nathan married a third time, and his wife, Louisa Taylor, was thirty-one years his junior. They eventually separated.

Warren died on June 3, 1888, at 813 Arch Street in Little Rock. He was memorialized the next day “under the auspices of the Richmond Masonic Lodge No. 1,” as he was not only a charter member but also rose to the rank of thirty-third-degree Mason in the Prince Hall Masons. The funeral was held at Bethel AME on the corner of 9th and Broadway streets.

Warren was buried in Mount Holly Cemetery in Little Rock in the Chester Ashley plot. An obelisk was placed as a headstone on his grave by Bethel AME Church and the Richmond Masonic Lodge No. 1. During the Jim Crow era, the headstone was either removed from his gravesite by cemetery authorities or stolen by vandals. Over time, the exact location of the grave was lost to memory, but in 2013, Warren’s gravesite was thoroughly researched and again located.

For additional information:

“Died.” Arkansas Democrat, June 4, 1888, p. 4.

Lack, Paul D. “An Urban Slave Community: Little Rock, 1831–1862.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 41 (Autumn 1982): 258–287.

“Local Items.” Arkansas Gazette, June 5, 1888, p. 5.

Ross, Margaret Smith. “Nathan Warren, a Free Negro for the Old South.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 15 (Spring 1956): 53–61.

Taylor, Orville W. Negro Slavery in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

James Medrick “Butch” Warren

Historic Arkansas Museum Commission

Business, Commerce, and Industry

Business, Commerce, and Industry Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860 Nathan Warren

Nathan Warren

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.