calsfoundation@cals.org

Far West Seminary

In the mid-1840s, the Far West Seminary, a planned collegiate-level educational institution in northwest Arkansas, failed due to political and religious factionalism, economic hard times, and a major fire. However, the effort proved to be a seedbed for other northwest Arkansas educational endeavors prior to the Civil War that helped Fayetteville (Washington County) earn the nickname “the Athens of Arkansas.”

After the state failed to use its federal seminary grant to create a state university, northwest Arkansas educators and promoters in 1840 began discussing the need for a facility for higher education. On August 12, 1843, a group of interested citizens gathered at the Mount Comfort Meeting House, located three miles northwest of Fayetteville. This meeting resulted in the creation of a committee of seven persons to recommend a plan, fundamental principles, a name, and a location. Subsequently, prominent members included the Reverend Cephas Washburn, Isaac Murphy, David Walker, and Alfred W. Arrington. A founder of the Cherokee school Dwight Mission and its successor in Indian Territory, Washburn relocated to northwest Arkansas and was the person most closely identified with the project. Murphy, a future governor, taught school and later practiced law. Walker, the leading lawyer in the region, served on the Arkansas Supreme Court. Arrington, who had come to Arkansas as a Methodist minister, later switched to law and then literature.

The committee made its report on September 27, 1843. They chose the name “Far West Seminary” in order to emphasize the western location of the planned institution. The site chosen was near a spring on land donated by Solomon Tuttle. The committee also drew up a constitution for the proposed school. While the Bible was declared to be “the standard of Morals and Religion,” the school was never to “possess a sectarian character in religion or a party character in politics.” The founders envisioned not only the traditional classical education but also instruction in agriculture and the mechanical arts.

The committee also created a board of visitors that reflected the wide range from which the school hoped to draw. From outside of Arkansas came Springfield, Missouri, Democratic congressman John Smith Phelps; from the Cherokee Nation, Jesse Busheyhead. Seven Arkansas counties were represented on the board. The overwhelming membership consisted of Whigs and Presbyterians. George Washington Paschal of Van Buren (Crawford County) was one notable Democrat.

One opponent of the school attacked its plan to avoid sectarianism; another asserted that education fostered “pride and ambition” and so was “dangerous to our liberties.” In response, Paschal chaired a committee that published a strong letter of support. One argument was the claim that establishing a seminary would encourage good primary schools to start up. Another argument—doubtless in response to the raising of the sectarian issue—was that the school was needed to offset “the dangerous strides of Popish and Jesuitical influence.”

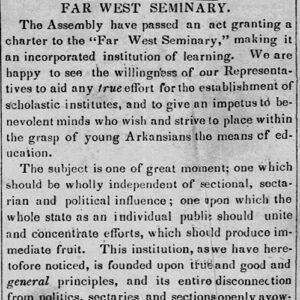

After opening subscription books, backers sought a state charter. At this point, Democratic opposition, probably based mostly on sectarian and partisan grounds, surfaced, with five northwest Arkansas legislators voting against giving the school a charter. The Whig editor of the Arkansas Gazette concluded that Democrats were just ignorant: “[I]t is a principle with them never to encourage institutions of learning.”

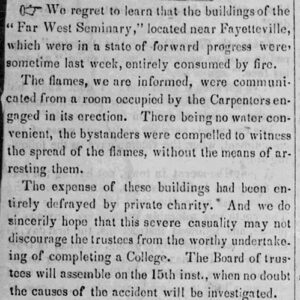

Despite sectarian and political opposition, the charter bill passed. The project’s timing could not have been worse. The collapse of Arkansas’s banking system (the State Bank and the Real Estate Bank) limited contributions. Enough money did come in, however, to get construction under way. On February 27, 1845, an accidental fire destroyed the nearly finished building. Some board members were determined to rebuild, and Washburn went on a tour in hopes of raising money. However, the deepening depression ended these hopes. Paschal decamped for Texas, and in 1847, the school’s creditors filed suits that ended with the liquidation of the property.

The role the school played as a seedbed for education in northwest Arkansas has been much misunderstood, especially on historical markers. Far West Seminary is arguably the most important school that Arkansas never had, given that those involved with it later participated in other educational ventures. Board member Robert W. Mecklin anticipated the establishment of the Far West Seminary by establishing his own primary school at Mount Comfort (Washington County). Mecklin later purchased the former seminary lands, where his Ozark Institute flourished in the 1850s. Far West Seminary supporter David Walker, writing Mecklin’s obituary in 1871, recalled that Mecklin “was far in advance of us” and that his Ozark Institute was the “best High School in the State.” One of Mecklin’s assistants was the Reverend Robert Graham, who founded Arkansas College in Fayetteville in 1852. Cane Hill College was not far distant, and after the Civil War, Fayetteville successfully won the bid for the state public university.

For additional information:

Arkansas Intelligencer (Van Buren), January 13, 1844, p. 2; January 27, 1844, p. 3; February 3, 1844, p. 2; February 17, 1844, p. 2; May 4, 1844, p. 2.

Carter, Dean G. “Some Historical Notes on Far West Seminary.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 29 (Winter 1970): 345–360.

Lemke, W. J. Early Colleges and Academies of Washington County. Fayetteville, AR: Washington County Historical Society, 1954.

Michael B. Dougan

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Far West Seminary Story

Far West Seminary Story  Far West Seminary Story

Far West Seminary Story

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.