calsfoundation@cals.org

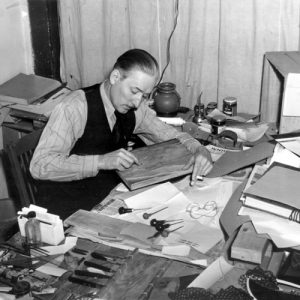

Adrian Louis Brewer (1891–1956)

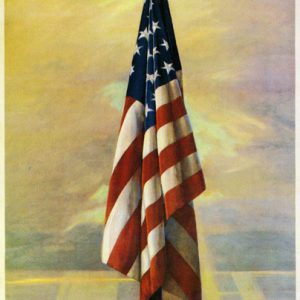

Adrian Louis Brewer, a native of Minnesota, is known in Arkansas primarily for his portraits of prominent citizens, but his artistic genius lay in pastoral landscape paintings of the Southwest and rural scenes of Arkansas, his adopted state. Brewer’s work was influenced by the American Impressionists and reflected the restlessness of modern artists. David Durst, a professor of art at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County), credited him with contributing to the “healthy stature” of art and art activities in Arkansas and keeping “the spark of aesthetic sensibility alive during the difficult years of cultural neglect.” Probably his most famous painting is the 1941 “Sentinel of Freedom,” which has been reproduced millions of times and has received wide distribution in America and abroad.

Adrian Brewer, born on October 2, 1891, in St. Paul, Minnesota, was one of six sons of artist Nicholas Richard (N. R.) Brewer and Rose Koempel Brewer. He was named after the seventeenth-century Flemish artist Adriaen Brouwer. Brewer was greatly influenced by the life and art of his father, who was known in the art communities of New York, Minneapolis, Chicago, California, and the Southwest as a portrait painter. He had been represented in exhibitions of the National Academy of Design in New York since 1885.

The Brewer family moved back and forth between Minnesota and New York several times during Brewer’s childhood. In 1909, he attended St. Thomas College, a preparatory school in St. Paul, now a university, but soon left because the strict Catholic curriculum did not afford him the luxury of reading and studying the books he wanted. He enrolled as an art student at the University of Minnesota (UM) in 1911.

While attending classes at UM, Brewer began art studies at the Art Institute of St. Paul under Delle E. Randall. He enrolled for a short time at the Art Students’ League in New York City, where he was able to learn from well-known artists in their studios. He learned more about art from some of his father’s associates than from his classes.

Though he did not earn a degree, he went back to St. Paul around 1915 and taught for two years at the art institutes in both St. Paul and Minneapolis. He then opened a commercial art studio in Minneapolis and did advertising work for a number of companies.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, Brewer enlisted in the 444th Aero Construction Squadron. Because of his artistic talent, however, he was assigned to what one national periodical termed “the most unique advertising campaign in America,” advertising for patriotism. His posters, cartoons, and paintings were distributed throughout the Pacific Coast states to enlist popular support for the war effort. His artwork for the 444th Aero Squadron publications and his portrait of Brigadier General Brice Disque led to his commission as a second lieutenant.

In 1917, he was also traveling with his father to various regions of the United States as his father’s business manager and assistant while painting landscapes, which he was able to do during wartime as he had a desk job that allowed him to leave at different intervals. He won a bronze medal for his entry Mississippi in Winter in a 1917 competition at the St. Paul Institute of Art.

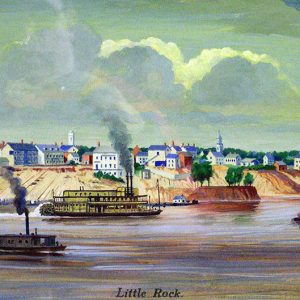

Brewer continued his studies with a number of prominent artists in Chicago. In 1920, Brewer, just discharged from the military, accompanied his father to Hot Springs (Garland County) to help him with commissioned portraits; the elder Brewer had, the previous year, come to Little Rock (Pulaski County) for an exhibition of his paintings sponsored by the Art Association of Little Rock. While helping his father in a portrait studio they set up in the Eastman Hotel, Brewer met Edwina Cook and spent the winter in Hot Springs courting her. He returned to Minneapolis to teach for a year as instructor of drawing and painting at the Minneapolis and St. Paul art institutes. He also became a faculty art critic for the Federal Schools Inc., writing critiques for The Federal Illustrator. He returned to Hot Springs in 1920 to marry Cook on February 15, 1921. They eventually had children.

Soon after his marriage, Brewer moved back to Minneapolis, where he took a job as sketch artist for the Thomas Cusack Company. He soon grew dissatisfied with advertising and became manager of his father’s exhibitions in the South and Midwest during the next few years, while still painting landscapes. He traveled extensively through Texas, Arkansas, and New Mexico, perfecting his style and trying to support his family. Patrons in Texas and Arkansas who had been made wealthy by the oil boom provided him a living from portrait painting and also afforded him time to experiment with plein air painting—that is, painting outdoors.

After a trip to Austin, Texas, with his father in April 1928 to paint the fields of bluebonnets, Brewer received the Edgar B. Davis first prize of $2,500 for his painting In a Bluebonnet Year at an exhibition sponsored by the San Antonio Art League, which still has the bluebonnet painting in its collection. After exhibiting and selling bluebonnet paintings in Texas and New York, he decided to go in a different direction. He went to Arizona, Texas, and New Mexico, where he produced 126 western landscapes. Brewer’s ability to take almost destitute settings and transform them into dreamlike, romantic places became his trademark.

During the late 1920s and early 1930s, Brewer also painted Arkansas landscapes, frequently choosing a high vantage point, such as Petit Jean Mountain (Conway County) or Mount Gaylor (Crawford and Washington counties), for panoramic vistas of lush river valleys or Ozark hills. Experience gained on his trips to Texas and New Mexico affected the Arkansas landscapes. The quasi-impressionist style remained, but in the Arkansas paintings, the light and colors changed less, and the natural detail is almost photographic; dabs of strong color indicate a more romantic approach to nature.

In 1933, Brewer established the Adrian Brewer School of Art in downtown Little Rock, with the help of Powell Scott, a painter and lithographer at the Chicago Art Institute who had met Brewer there in 1930. The school, located at 105 West 8th Street, enrolled about thirty students the first year. During lesson breaks, students were entertained by accomplished artists in other fields: John Gould Fletcher would recite poetry, or Josef Rosenberg would play the piano, or Max Mayer would lecture on architecture or play his violin. Though the school was academically successful, the economic conditions of the Depression caused it to close in 1933.

Though he had painted portraits before, in 1929, Brewer began portrait painting in earnest to support himself, painting over 300 Arkansans in his lifetime. In 1934, he painted the portrait of U.S. Senator Joseph T. Robinson that now hangs in the Arkansas State Capitol. Senator Robinson secured an invitation for Brewer to paint a portrait of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, but he surrendered his opportunity and gave the appointment to his seventy-seven-year-old father. Brewer later painted the portraits of many Arkansas notables, including politicians and university presidents.

In 1935–36, Brewer went to New York to produce portraits of society notables, including Mr. and Mrs. Allan Bond, who gave him an entire floor of the Bond Building to use as his studio for a year. In 1940, he painted a portrait of an Ozark man entitled Hillbilly; for this he received a medal and cash prize from International Business Machines (IBM). This portrait also won the John Flannagan Gold Medal from the Gallery of Science and Art at the San Francisco Golden Gate International Exposition that same year.

During World War II, Brewer’s talent was again used in the war effort. In 1942, he produced a print used for the cover of an autographic roster and record. U.S. service personnel carried copies of this book as mementos of service. Brewer was also in charge of the art classes for servicemen at the United Service Organization (USO) in Little Rock. Gene Kelly, the dancer and actor, was among the members of his class. Brewer and Adele Guckert, who went on to form the Arkansas Arts Center (now the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts), took the students on tours to paint watercolors of famous Arkansas homes and structures. His USO class was photographed by Life magazine while on one of the tours. Brewer supervised the soldiers in painting a giant mural at the USO club on Third and Main in Little Rock.

It was also during the war that Brewer embarked on a project to bring Arkansas art to the state’s average citizens. He created a series of woodcuts of well-known Arkansas landmarks, produced as postcard-type prints with the help of his young twin sons, Adrian Jr. and Edwin. Brewer was determined to use only Arkansas-produced paper and frames made from local lumber. The prints were sold in retail stores and gift shops throughout the state.

After the war, Brewer moved his studio from downtown Little Rock to his home at 510 North Cedar Street. He and his sons built the studio, designed by architects Max Mayer and George Trapp, in the back of his home.

In 1953, Brewer and his son Edwin organized the Arkansas Art League, which, with the Arkansas Power and Light Company as sponsor, held the Arkansas Art League competition, Portrait of Power, in 1954. In 1955, Brewer was among just a handful of artists invited to represent Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Oklahoma at the Contemporary Art Show of the Southwest, sponsored by Stephen F. Austin State College in Nacogdoches, Texas. For this exhibit, which was his last, he produced a somewhat abstract self-portrait, Mirrors.

Brewer died of lung cancer on June 23, 1956.

For additional information:

Fletcher, John L. “Adrian Brewer—The Portrait of an Artist.” Arkansas Gazette, January 11, 1953.

Halinski, Jolynda Hammock. “Adrian Louis Brewer (1891–1956): Visions of an Arkansas Painter.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 1997.

“Portraitist Left Mark with Efforts.” Arkansas Democrat, March 28, 1986.

Jolynda Hammock Halinski

Vicksburg, Mississippi

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment Adrian Brewer

Adrian Brewer  Harvey Couch

Harvey Couch  Arthur Harding

Arthur Harding  Jesse C. Hart

Jesse C. Hart  Little Rock

Little Rock  Sentinel of Freedom

Sentinel of Freedom

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.