calsfoundation@cals.org

Civil Rights and Social Change

What exactly constitutes “rights” and who holds them has changed over time. The 1776 Declaration of Independence famously declared “that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” This is a very broad conceptualization of what are often termed “natural” or “human” rights. The idea of civil rights has a much narrower definition, being those rights specifically ascribed to citizens by governments. This entry examines the evolution of civil rights in the United States and how they have impacted Arkansans since the Civil War. Its particular focus is on how civil rights and citizenship were expanded through the social changes that occurred in the period.

Civil War through Reconstruction

At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, civil rights were largely defined by the Bill of Rights, the first ten amendments added to the U.S. Constitution in 1791. These granted specific personal freedoms and limited the power of federal government over individuals. Crucially, the question of what it meant to be a citizen of the United States—an important factor in determining who possessed civil rights—was still ill-defined. Certain groups were specifically excluded from citizenship. African-American slaves were considered property rather than people. Most Native Americans were also not considered citizens of the United States. Whether women’s rights were guaranteed under the Constitution was a hotly debated topic.

Much of the modern concept of civil rights stems from the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution, often referred to collectively as the Reconstruction or Civil Rights Amendments. The Thirteenth Amendment (ratified in 1865) outlawed slavery in the United States. The Fourteenth Amendment (ratified in 1868) guaranteed that no state could “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law” and assured “equal protection of the laws.” It also for the first time defined U.S. citizenship as encompassing “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” The Fifteenth Amendment (ratified in 1870) guaranteed the right to vote without “account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

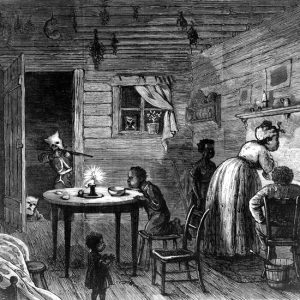

The primary aim of the Reconstruction Amendments was to ensure the civil rights of freed slaves, of which there were an estimated 110,000 in Arkansas. One of the earliest efforts to manage the transition from slavery to freedom, and to help African Americans to exercise their newfound rights, was the creation of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (a.k.a. Freedmen’s Bureau) in 1865.

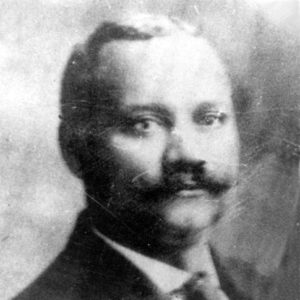

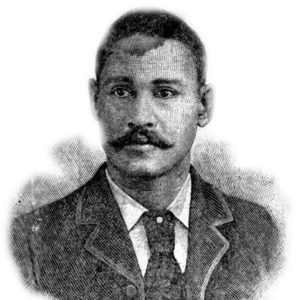

A number of African Americans won prominent political positions during Reconstruction through the right to participate in politics. William Hines Furbush was elected to the Arkansas General Assembly. Isaac Taylor Gillam was elected to the city council of Little Rock (Pulaski County), the Arkansas General Assembly, and as Pulaski County coroner. Prominent lawyer Miffiln Wistar Gibbs was appointed as a Little Rock police judge. Ferdinand Havis was elected as a Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) alderman, state representative, assessor, and county clerk. Joseph Carter Corbin served as Arkansas’s superintendent of public instruction.

Nevertheless, the rights of African Americans were limited. The vast majority of the state’s black population has resided in the Arkansas Delta since 1861. Economically disadvantaged, many were forced into exploitative sharecropping and tenant farming contracts with white landowners. White violence such as whitecapping, nightriding, and lynching, sometimes orchestrated by white terror groups such as the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), provided extralegal means of denying African Americans the ability to exercise their civil rights in a number of ways—from, for example, preventing or dissuading them from voting, to the ultimate denial of civil rights by unlawful murder. The education system set up in Arkansas during Reconstruction was segregated by race, a forerunner of a more pervasive expansion of Jim Crow laws in the post-Reconstruction era.

Following the Fifteenth Amendment’s guarantee of voting rights to African Americans, women also fought for the right to vote. However, when the idea of women’s suffrage was proposed at the Arkansas Constitutional Convention in 1868, it was emphatically rejected. Black women and their male partners used their newfound freedom to have their marriages legally recognized for the first time, thereby stabilizing and strengthening their families. While denied the right to vote, black women also benefitted from political and social changes by holding prominent roles during Reconstruction. Charlotte Andrews Stephens was appointed as the first black teacher in the Little Rock schools in 1869, the first of many such women to enter the profession in that city and across the state.

For Native Americans, the Civil War and Reconstruction only extended their previous disruption and displacement in Arkansas and underscored their lack of citizenship and thereby their lack of civil rights. General Albert Pike was appointed by Confederate president Jefferson Davis as commissioner to the Indian Territory tribes. Pike organized a Confederate Indian army of Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek (Muscogee), and Seminole Indians. The slave-owning history of those tribes aligned them with the Confederate cause. When Confederate promises of support and protection in return for service failed to materialize, many fled to Union-held Kansas. Returning at the end of the war, Native American tribes often found their former lands destroyed. During Reconstruction, U.S. Indian agents imposed harsh penalties on tribes in retaliation for alliances with the Confederacy.

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

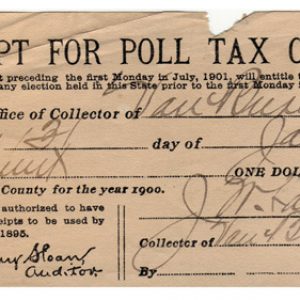

The return of the Democratic Party to political power in Arkansas in 1874 effectively brought Reconstruction to an end. This, in turn, led to a gradual erosion of African Americans’ civil rights. Disfranchisement was achieved by two means. The first was a secret ballot law passed in 1891 that required illiterate voters to have election judges mark their ballots. This handed power to people who were not predisposed to uphold black voting rights. The second was a one-dollar poll tax that placed a financial burden on the poorest segments of the population, including many African Americans. The poll tax was established by an amendment to the state constitution in 1892. After it was voided by the courts, a new poll tax amendment was introduced in 1908.

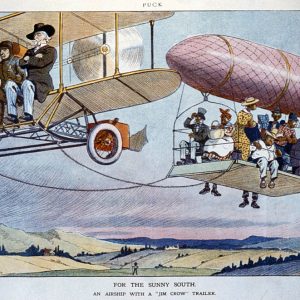

Jim Crow laws in Arkansas began with the Separate Coach Law of 1891. Other laws soon followed requiring the segregation of African Americans and whites in virtually every aspect of life. In the case of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the U.S. Supreme Court mandated the use of racial segregation, claiming that it did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of “equal treatment” under the law. The Court ruled that facilities for the races could be kept “separate” so long as they remained of “equal” standard. In reality, this was hardly ever the case, and separate facilities remained distinctly unequal. The threat and reality of extralegal white violence underpinned the enforcement of segregation laws. The number of lynchings in Arkansas reached its peak in the 1890s.

African Americans responded to disfranchisement and segregation in various ways. Some left the United States as the Back-to-Africa Movement gained popularity. Many of those who could afford to left the South for other parts of the United States. Those who stayed had two options. One was to protest and to fight injustice through direct action and the courts. The other was to accept the limitations placed upon them in a society where they were outnumbered and outgunned by whites. African Americans formed and sustained networks of self-support through schools, churches, fraternities and sororities, businesses, groups, civil associations, and political organizations. These groups provided help and sustenance in times when African Americans lacked formal civil rights and protection under the law. One of the most prominent of these organizations was the Mosaic Templars of America based in Little Rock, a fraternal organization offering mutual aid to the black community. In rural areas, agricultural workers joined various farm movements to fight for better conditions.

Arkansas women continued to fight for the right to vote. In 1881, Eureka Springs (Carroll County) resident Lizzie Dorman Fyler founded and led the Arkansas Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). It disbanded in 1885, a month before Fyler’s death. In 1888, Kansas City lawyer Clara McDiarmid organized the Arkansas Equal Suffrage Association (AESA). She wrote articles for Little Rock’s women’s suffrage magazine Woman’s Chronicle and attended National Women’s Suffrage Association meetings. However, with her death in 1899, the movement for women’s suffrage in Arkansas was left leaderless, and the AESA disbanded soon after.

The passage of the Dawes Act of 1887 by the U.S. Congress was a pivotal turning point in Native American rights. Known also as the Indian Allotment Act, it subdivided reservation lands into parcels of about 160 acres and allotted them to individual families. Remaining parcels of land were publicly sold. The act broke up large Indian landholdings, bringing to an end the multi-family networks of cooperation that were at the heart of Indian communities. A concerted effort to assimilate Native Americans into American society led to a widespread attack on Native American life and culture. Native languages, social systems, political institutions, religious beliefs, and even clothing and hairstyles all came under assault. Although there were no large Native American landholdings in Arkansas covered by the Dawes Act, displaced Arkansas tribes in other states were affected by this legislation.

The struggle of workers for the right to organize, a right not formally recognized by the U.S. government until the 1930s, developed sporadically in Arkansas. It gained a boost in the mid-1880s with the arrival of the national Knights of Labor union. By 1886, the Knights had almost 3,000 members in Arkansas, concentrated mostly in the larger railroad towns. Although the Knights then went into decline nationally, in Arkansas they continued to grow with the addition of coal miners in the western part of the state and black agricultural workers in the Delta, raising membership to almost 5,400. Although officially nonpartisan, the Knights’ leaders joined with the Agricultural Wheel and the Union Labor Party in 1888 in calls for regulation of mines and trusts, the elimination of convict labor, currency and bank reform, and the expansion of the state’s education system. This cost the Knights support and members, and their position was further eroded in the 1890s when they lost out to the increasingly popular Farmers’ Alliance.

Early Twentieth Century

African Americans found themselves increasingly subject to Jim Crow laws at the start of the twentieth century. The Streetcar Segregation Act of 1903 provided for separate sections on city streetcars. Black riders in Little Rock, Pine Bluff, and Hot Springs (Garland County) boycotted streetcars in protest. Although lynching abated somewhat, episodes such as the St. Charles Lynching of 1904 attested to the continuing use of violence as a means of controlling the African-American population. In 1919, the Elaine Massacre led to possibly hundreds of black men, women, and children being killed by an armed white mob. By no means was all racial violence limited to rural areas, as the 1906 Argenta Race Riot and the 1927 lynching of John Carter in Little Rock demonstrated. The formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909 provided the first national civil rights organization. NAACP lawyers, with the help of black Little Rock lawyer Scipio Africanus Jones, helped defend twelve black men sentenced to death for their alleged role in events at Elaine (Phillips County). The first NAACP branch in Arkansas was set up in Little Rock in 1918.

The exclusion of black voters from meaningful participation in state politics was completed in 1906 when all-white party primaries were established by Arkansas’s Democratic Party. Since Arkansas was virtually a one-party state, exclusion from the primaries had dire consequences. It meant that, even if they could afford the one-dollar poll tax to vote at a general election, black voters could no longer have any say in the choice of the Democratic candidate who would invariably win it. In 1928, Little Rock physician Dr. John Marshall Robinson helped to found, and became president of, the Arkansas Negro Democratic Association (ANDA). Robinson and ANDA challenged the all-white Democratic Party primaries in the courts in Robinson v. Holman (1928). The Arkansas Supreme Court ruled in favor of the all-white primaries, and the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the case on appeal.

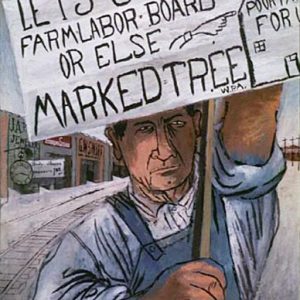

The onset of the Great Depression and the initial response of the New Deal made things worse for many black and white tenant farmers and sharecroppers in the Arkansas Delta. The Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA)—from 1942 called the Agricultural Adjustment Agency—targeted landowners rather than farmers for compensatory payments. The National Labor Relations Act of 1935 and other New Deal legislation explicitly excluded agricultural workers. In a rare show of interracial unity, black and white farmers banded together to form the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU) in 1934. Although ultimately unsuccessful in achieving its goals, the STFU brought the plight of Delta farmers to national attention.

The mechanization and urbanization of Delta agriculture precipitated by New Deal policies led to African Americans moving off the land and into growing towns and cities. Larger urban black communities and the networks of support that developed within them were important precursors to later civil rights struggles. Among the first to build upon these developments was Pine Bluff lawyer William Harold Flowers, who formed the Committee on Negro Organizations (CNO) in 1940 to coordinate voter registration drives in the state.

Women’s suffrage advocates won landmark victories, gaining the right to vote in primary elections in 1917 and in general elections in 1920. In part, this success followed the political mobilization of people, predominantly churchwomen, in Prohibition campaigns. It also followed the rejuvenation of the women’s suffrage movement in 1911 with the founding of the Political Equality League (PEL). Initial efforts to gain the franchise by an amendment to the Arkansas state constitution were opposed by liquor interests, who believed that women’s votes would threaten their operation. In 1914, the Arkansas Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) formed, and the PEL merged the following year with the Arkansas Federation of Women’s Clubs (AFWC). In 1915, a women’s suffrage amendment to the Arkansas state constitution was passed but not adopted.

In 1917, the legislature passed a bill allowing women to vote in primary elections. The following year, more than 40,000 women voted in statewide primaries, and over fifty female delegates were elected to the Democratic State Convention. After another failed attempt to amend the state constitution, with the support of Governor Charles Hillman Brough, in 1919, the legislature ratified the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which granted women the right to vote. It became law on August 26, 1920. This success led to the formation of the Arkansas League of Women Voters (ALWV), which became the leading advocate for women’s rights in the state. The period also marked another notable first in Arkansas women’s history when Hattie Caraway became the first woman elected to the U.S. Senate.

In 1924, the Indian Citizenship Act paved the way for all Native Americans to be considered citizens of the United States. The New Deal further extended Native Americans’ rights. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 shaped the Indian New Deal. Albeit with some constraints, the act marked a significant policy change by devolving responsibilities for governance back to tribes. John Collier, appointed commissioner of Indian Affairs by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, oversaw much of the Indian New Deal. He actively promoted tribal heritage and culture. Under the New Deal, the Caddo and Quapaw tribes adopted new constitutions and organized new governing councils. The Osage and Cherokee revised previously created constitutions and governing bodies. Although the Indian New Deal represented an improvement on the policies promulgated by the Dawes Act, it still left Native Americans with difficulties in adapting to new tribal structures. As with the Dawes Act, the depleted number of Native Americans in Arkansas meant that the Indian New Deal had a more profound impact on displaced Arkansas tribes residing in other states.

The New Deal also marked a turning point for the labor movement. An Arkansas State Federation of Labor (ASFL) had formed in 1904 and affiliated with the national American Federation of Labor (AFL). It won a number of legislative successes, including the passage of a minimum wage for women, restriction of child labor, regulation of prison labor, and prohibition of the blacklisting of union members. It also banned the payment of wages in scrip and established the Arkansas Bureau of Labor and Statistics. It met with violent opposition. In 1923, civic leaders in Harrison (Boone County), in partnership with the Ku Klux Klan, hanged a striking railroader and marched nearly 200 strikers to the Missouri line in the Harrison Railroad Riot.

New Deal legislation fulfilled the long struggle for workers’ right to organize. The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 and the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 promised federal protection for industrial workers to organize and required collective bargaining by employers. By 1939, the number of organized workers in the state stood at 25,000. Building on this support, the ASFL launched successful campaigns to create unemployment and workmen’s compensation programs. In 1936, a national split developed between the national AFL, representing mainly skilled trade workers, and the Committee on Industrial Organization (the CIO, formed in 1935 and in 1938 renamed the Congress on Industrial Organization), representing mainly unskilled industrial workers. The following year this split was replicated in Arkansas when CIO unions broke with the ASFL to form the Arkansas Industrial Council (AIC).

World War II through the Faubus Era

Increasingly assertive presidential action and a U.S. Supreme Court shaped by Roosevelt’s appointments and sharing the New Deal’s socially progressive outlook, together with national calls for greater freedom and equality, led African Americans in Arkansas to fight for civil rights with enhanced expectations of change. In 1942, the Arkansas State Press won the appointment of the first black police officers in Little Rock following an outcry after a white city policeman shot and killed a black army sergeant. The same year, black teacher Sue Cowan Williams (then known by the last name Morris), with the assistance of the NAACP, sued for equal teachers’ salaries with whites. She won the case on appeal in 1945. In 1944, the Texas case of Smith v. Allwright ruled an end to the all-white Democratic Party primaries. The Little Rock NAACP branch successfully sued for the rights of African Americans to stand as Democratic Party candidates in 1950. That year, the Democratic Party dropped all barriers to black membership and participation. African Americans also benefited from wartime employment gains in defense industries through the Fair Employment Act of 1941. Many black soldiers served in a segregated U.S. military both at home and abroad, which in many cases allowed them to experience life outside of the state beyond the bounds of Jim Crow. The U.S. military was desegregated in 1948 by President Harry S. Truman’s Executive Order 9981. Also in 1948, under pressure from local black activists and national court rulings, the University of Arkansas School of Law admitted Silas Hunt, its first black student since Reconstruction. Edith Irby became the first black student to enroll at the School of Medicine of the University of Arkansas (now the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences) in Little Rock later that year.

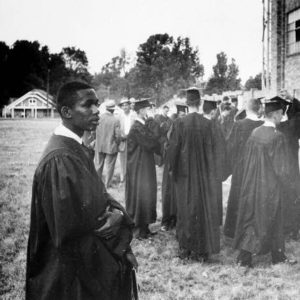

The civil rights struggle intensified after the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954) school desegregation ruling. Fayetteville (Washington County) and Charleston (Franklin County) in northwest Arkansas were the first districts in the South to desegregate. Similar attempts in Sheridan (Grant County), closer to the Arkansas Delta, were quickly reversed. In 1955, Hoxie (Lawrence County), a small town in northeast Arkansas, encountered difficulties when it desegregated schools. The school board won a landmark court ruling to keep schools integrated.

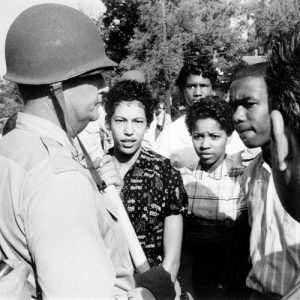

Events came to a head in Little Rock in September 1957 when Governor Orval Faubus’s decision to call out the Arkansas National Guard prevented the entry of the Little Rock Nine into Central High School. The Little Rock crisis ended with President Dwight D. Eisenhower federalizing the National Guard and sending in federal troops to escort and protect the nine students, who were mentored locally by state NAACP president Daisy Bates and her husband, L. C. Bates. The following year, Faubus closed all of the city’s schools, and white voters mandated his actions in a referendum. Only when moderate candidates won places on the school board did Little Rock schools reopen on a token integrated basis in 1959. Concerted efforts to desegregate schools statewide did not begin until after the U.S. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Little Rock was an important base for the expansion of the civil rights movement in the 1960s. Philander Smith College students held sit-ins in 1960, but harsh fines and stiff jail sentences swiftly ground the movement to a halt. The 1961 Freedom Rides had a limited impact. In late 1962, the interracial Arkansas Council on Human Relations (ACHR) looked to revive sit-ins by requesting assistance from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in Atlanta. The SNCC sent white student William Hansen. Together with Philander Smith student Worth Long and others, Hansen ran sit-ins that finally brought a response from downtown merchants. Over the first six months of 1963, most downtown facilities quietly desegregated. A new community organization of black professionals, the Council on Community Affairs (COCA), helped to oversee the process.

Hansen went on to establish SNCC project centers in Pine Bluff, Forrest City (St. Francis County), Gould (Lincoln County), and Helena (Phillips County). From those bases, SNCC conducted voter registration drives and direct action protests before disbanding in 1967. Although facing greater opposition and hostility in these places, they were successful in helping to raise the number of registered black voters. They were helped in this by the Twenty-Fourth Amendment (ratified in 1964), which prohibited payment of a poll tax as a voting qualification, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Their efforts were also boosted by the active courting of the African-American vote by wealthy reformist Republican Winthrop Rockefeller in his successful 1966 and 1968 campaigns for governor.

Wartime industries brought new opportunities for Arkansas women, though on a lesser scale than nationally. Despite union membership, women’s wages remained less than those of their male counterparts. Women also played important roles in the civil rights struggles in the state. Pro-desegregation forces were most visible in the Women’s Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools (WEC), led by women such as Adolphine Terry and Vivion Brewer, which campaigned to reopen closed schools in Little Rock in 1958–59. Anti-desegregation forces were most visible in the Mother’s League of Central High School. Many women in the WEC remained politically active and played an important role in Winthrop Rockefeller’s successful campaigns for governor. A reflection of women’s growing political influence in the state, Dorathy Allen of Brinkley (Monroe County) was the first woman to be elected to the Arkansas State Senate in 1964.

Wartime production led to increased union membership in Arkansas, standing at 43,000 in 1944. By 1955, it rose to 75,000. With increased membership came growing opposition. In 1943, the Christian American Association (CAA) was successful in passing legislation limiting the rights of union members to picket during strikes. The following year, it joined forces with the Arkansas Free Enterprise Association to pass a “right-to-work” law forbidding union membership as a condition of employment.

In 1955, the AFL and CIO merged at a national level. The ASFL and AIC followed suit in March 1956. The resulting Arkansas State Federated Labor Council (later the Arkansas AFL-CIO) set out an ambitious legislative agenda. According to Arkansas labor historian Michael Pierce, “The labor movement took the lead in the creation of a liberal coalition that convinced the General Assembly to pass measures that helped all workers regardless of union affiliation: increases in workers’ compensation and unemployment benefits, replacement of the poll tax with a voter registration system, and passage of a minimum wage law.” The Arkansas AFL-CIO, however, failed in attempts to overturn to state’s right-to-work law and to win collective bargaining rights for public employees.

The wartime experience did not enhance everyone’s civil rights. In 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which created exclusion zones in the interests of national security. In practice, this meant the relocation of approximately 110,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast. By the end of the year, around 17,000 internees were relocated to Arkansas camps at Rohwer (Desha County) and Jerome (Drew County), abrogating their civil rights. In 1943, Governor Homer Adkins signed a bill to prohibit Japanese-American property ownership in Arkansas. Many chose to leave the state at the end of the war. Internees were issued a national apology in 1988 during President Ronald Reagan’s administration, and reparations were paid to survivors and heirs.

In 1953, federal policy toward Native Americans took another dramatic shift. Termination Policy ended the Bureau of Indian Affairs and its programs. Tribal property was distributed among its members, tribal self-government was curtailed, and many Native Americans were relocated to urban areas where jobs were available. Termination also ended federal responsibility for social services such as education, health, and welfare. This policy lasted into the 1960s. Again, this had a dramatic impact on displaced Arkansas tribes outside of the state.

Modern Era

The growing political power of black Arkansans during the 1960s came to fruition in the 1970s. In 1972, Arkansas had ninety-nine black elected officials, the second highest number of any Southern state. The same year, Little Rock optometrist Dr. Jerry Jewell became the first black member of the Arkansas Senate in the twentieth century. Dr. William Townsend became one of three African Americans elected to the Arkansas House of Representatives. Lawyer Perlesta A. Hollingsworth became the first black member of the city directors’ board in Little Rock. Throughout the state, African Americans won elective offices as aldermen, mayors, justices of the peace, school board members, city councilors, city recorders, and city clerks. These gains further stimulated black voter registration. By 1976, ninety-four percent of Arkansas’s voting-age African Americans were registered, the highest proportion of any state in the South.

But there are limits to change. Despite the gains in politics, Arkansas has still not elected a black governor or member of Congress. While public facilities are now comprehensively desegregated, after a period of busing in the early 1970s, schools in many parts of the state began to resegregate. This occurred for a number of reasons, including white flight from urban school districts and the construction of predominantly white private schools. On most quality of life indicators, including income, blacks still trail behind whites.

Women have continued to break down barriers to their advancement. In 1975, Elsijane T. Roy became the first female justice on the Arkansas Supreme Court. Jimmie Lou Fisher followed Nancy J. Hall as state treasurer from 1981 to 2002, and she became the state’s first woman gubernatorial candidate in 2002. Blanche Lambert Lincoln was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1998 and reelected in 2004. Hillary Rodham Clinton served as first lady from 1993 to 2001 during husband William Jefferson Clinton’s presidency. Her own campaigns for the presidency in 2008 and 2016 (as well as her service as a U.S. senator and U.S. secretary of state) made her the most successful woman candidate in U.S. history.

Again, there are limits to change. Arkansas was one of fifteen states that failed to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution in the 1970s. Women have continued to fight for reproductive rights after the landmark U.S. Supreme Court Roe v. Wade (1973) decision. While women in Arkansas earn the national average for women in the U.S., they remain less well paid than men. African-American women in particular are underrepresented in higher-earning jobs. In 1974, a Little Rock chapter of the National Organization of Women (NOW), an affiliate of the national organization founded in 1966, was founded to continue the fight for women’s rights.

The 1970s saw a return to a stress on Native American self-determination in federal policy. In 1975, the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, which increased tribal control on reservations and helped to fund new schools. The American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 expanded cultural freedoms of expression. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 permitted Indian tribes to reclaim artifacts and skeletal remains from museums and other federally funded institutions. Some Native American archaeological properties in Arkansas were designated as sacred sites under President Clinton’s 1996 Executive Order 13007 (“Accommodation of Sacred Sites”). As a result of these measures, modern Caddo, Cherokee, Osage, Quapaw, and Tunica tribes are beginning to reclaim their ancestral ties to Arkansas. However, continuing problems of poverty and alcoholism on reservations attest to the debilitating effects of ever-shifting federal policies.

As at a national level, the labor movement’s power in Arkansas peaked in the 1960s and declined thereafter. This was due to a number of factors, including foreign competition, a conservative ascendency in U.S. politics as the Democratic Party’s liberal agenda began to wane, and the emergence of anti-union or non-union companies such as Arkansas-based Walmart Inc. and J. B. Hunt. However, in 2018, voters approved a ballot measure to raise the minimum wage in the state from $8.50 per hour to $11 an hour by the beginning of 2021.

Latinos have figured in Arkansas’s history for centuries, but their rapid growth in numbers since the 1980s, particularly in northwest Arkansas, has made them a significant presence in recent decades. Civil rights issues have involved allegations of racial profiling over stops, searches, and investigations. In 2001, Latino residents in Rogers (Benton County) filed a class-action lawsuit against the city and police department that was settled out of court in 2003. Immigration has also been an important issue, especially in relation to undocumented Latino workers residing in the state. Arkansas Latinos have joined calls for the normalization of the status of such workers, of which there are an estimated 12 million in the United States. At present, undocumented Latino workers play a vital role in the state’s economy, but, without citizenship, they have no civil rights under the law.

Civil rights in terms of sexual orientation have become more prominent since the 1960s. The record on these issues in Arkansas has been mixed. Efforts to change the state’s sodomy laws were successful in Jegley v. Picado (2001). In 2003, a fourteen-year-old boy from Jacksonville (Pulaski County) won a right-to-privacy case after being “outed” by school officials. In 2004, Arkansas became one of eleven states with a law banning same-sex marriage. In 2006, the Arkansas Supreme Court lifted the ban on gays as foster parents. Arkansas is still one of only three states without hate-crime laws that cover gays and lesbians or laws prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation.

New civil rights organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) have succeeded old ones in the state. In some cases, there are palpable continuities in activism. For example, Little Rock businessman Fred K. Darragh was a founding member of both the Arkansas Council of Human Relations, which ceased to exist in 1974, and the ACLU of Arkansas, which was organized in 1969. The ACLU has been involved in a number of cases in the state concerning issues such as First Amendment rights to freedom of speech, press, religion, and assembly; the freedom to teach evolution in schools as with the landmark case of McLean v. Arkansas Board of Education (1981); women’s rights; gay and lesbian rights; and the rights of people with disabilities.

For additional information:

Adams, Julianne Lewis, and Tom DeBlack. Civil Obedience: An Oral History of School Desegregation in Fayetteville, Arkansas, 1954–1965. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

“Arkansas Women: Race, Reform, and the Right to Vote.” Special issue, Arkansas Historical Quarterly 79 (Autumn 2020).

Blevins, Brooks R. “The Strike and the Still: Anti-Radical Violence and the Ku Klux Klan in the Ozarks.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 52 (Winter 1993): 405–425.

Brewer, Vivion Lenon. The Embattled Ladies of Little Rock, 1958–1963: The Struggle to Save Public Education at Central High. Fort Bragg, CA: Lost Coast Press, 1999.

Buckelew, Richard. “Racial Violence in Arkansas: Lynchings and Mob Rule, 1860–1930.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 1999.

Cahill, Bernadette. Arkansas Women and the Right to Vote: The Little Rock Campaigns, 1868–1920. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2015.

Dougan, Michael A. “The Arkansas Married Woman’s Property Law.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 46 (Spring 1987): 3–26.

Finley, Randy. “Crossing the White Line: SNCC in Three Delta Towns, 1963–1967.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 65 (Summer 2006): 117–137.

Froelich, Jacqueline Ann. “The Gay and Lesbian Movement in Arkansas: An Investigation Study.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 1995.

Gordon, Fon Louise. Caste and Class: The Black Experience in Arkansas, 1880–1920. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995.

Graves, John William. Town and Country: Race Relations in an Urban-Rural Context, Arkansas, 1865–1905. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

Grubbs, Donald H. Cry from the Cotton: The Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union and the New Deal. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1971.

Haiken, Elizabeth. “‘The Lord Helps Those Who Help Themselves’: Black Laundresses in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1917–1921.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 49 (Spring 1990): 20–50.

Hild, Matthew. Arkansas’s Gilded Age: The Rise, Decline, and Legacy of Populism and Working-Class Protest. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2018.

———. Greenbackers, Knights of Labor, and Populists: Farmer-Labor Insurgency in the Late-Nineteenth-Century South. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007.

Holmes, William F. “The Arkansas Cotton Pickers Strike of 1891 and the Demise of the Colored Farmers’ Alliance.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 32 (Summer 1973): 107–119.

Jacoway, Elizabeth. Turn Away Thy Son: Little Rock, the Crisis That Shocked the Nation. New York: Free Press, 2007.

Jacoway, Elizabeth, and C. Fred Williams, eds. Understanding the Little Rock Crisis: An Exercise in Remembrance and Reconciliation. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1999.

Jones-Branch, Cherisse. Better Living by Their Own Bootstraps: Black Women’s Activism in Rural Arkansas, 1914–1965. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2021.

Kirk, John A. “Battle Cry of Freedom: Little Rock, Arkansas, and the Freedom Rides at Fifty.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 42 (August 2011): 76–103.

———. Beyond Little Rock: The Origins and Legacies of the Central High Crisis. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2007.

———. Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940–1970. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

Kirk, John A., ed. An Epitaph for Little Rock: A Fiftieth Anniversary Retrospective on the Central High Crisis. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2008.

Kousser, J. Morgan, ed. “A Black Protest in the ‘Era of Accommodation’: Documents.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 34 (Summer 1975): 149–175.

Lewis, Suzanne S. “The Wheelbarrow Strike of 1915: Union Solidarity in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 43 (Autumn 1984): 208–221.

Lewis, Todd. “Mob Justice in the ‘American Congo’: ‘Judge Lynch’ in Arkansas during the Decade after World War I.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 52 (Summer 1993): 56–184.

Lewis, Todd E., “Race Relations in Arkansas, 1910–1929.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 1995.

McGee, Holly Y. “‘It Was the Wrong Time, and They Just Weren’t Ready’: Direct-Action Protest in Pine Bluff, 1963.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 66 (Spring 2007): 18–42.

Miller, Laura A. “Challenging the Segregationist Power Structure in Little Rock.” In Throwing Off the Cloak of Privilege: White Southern Women Activists in the Civil Rights Era. Edited by Gail S. Murray. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004.

Moyers, David B. “Trouble in a Company Town: The Crossett Strike of 1940.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 48 (Spring 1989): 34–56.

Murphy, Sara. Breaking the Silence: Little Rock’s Women’s Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools, 1958–1963. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Riffel, Brent. “In the Storm: William Hansen and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Arkansas, 1962–1967.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 63 (Winter 2004): 404–419.

Riva, Sarah. “The Shallow End of the Deep South: Civil Rights Activism in Arkansas, 1865–1970.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2020. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3797/ (accessed August 30, 2022).

Ross, James D., Jr. “‘I Ain’t Got No Home in This World’: The Rise and Fall of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union in Arkansas.” PhD diss., Auburn University, 2004.

Sizer, Samuel A. “‘This is Union Man’s Country’: Sebastian County, 1914.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 27 (Winter 1968): 306–329.

Smith, C. Calvin. “The Politics of Evasion: Arkansas’ Reaction to Smith v. Allwright, 1944.” Journal of Negro History 67 (Spring 1982): 40–51.

———. “The Response of Arkansas to Prisoners of War and Japanese Americans in Arkansas, 1942–1945.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 53 (Autumn 1994): 340–364.

Stephan, Stephan A. “Desegregation of Higher Education in Arkansas.” Journal of Negro Education 27 (Summer 1958): 243–252.

Stockley, Grif. Daisy Bates: Civil Rights Crusader from Arkansas. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2005.

———. Ruled by Race: Black/White Relations in Arkansas from Slavery to the Present. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2008.

Stockley, Grif, Brian K. Mitchell, and Guy Lancaster. Blood in Their Eyes: The Elaine Massacre of 1919. Rev. ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020.

Stone, Jayme Millsap. “‘They Were Her Daughters’: Women and Grassroots Organizing for Social Justice in the Arkansas Delta, 1870–1970.” PhD diss., University of Memphis, 2010.

Taylor, Elizabeth A. “The Woman Suffrage Movement in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 15 (Spring 1956): 17–52.

Taylor, Kieran. “‘We Have Just Begun’: Black Organizing and White Response in the Arkansas Delta, 1919.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 58 (Autumn 1999): 265–284.

Thompson, Brock. “The Un-Natural State: Exploring Same-Sex Desire and Gender Identity in Arkansas from the Depression through the Clinton Era.” PhD diss., King’s College, University of London, 2006.

Turner, Ralph, and William Rogers. “Arkansas Labor in Revolt: Little Rock and the Great Southwestern Strike.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 24 (Spring 1965): 29–46.

Vervack, Jerry. “The Hoxie Imbroglio.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 48 (Spring 1989): 17–33.

Vinikas, Vincent. “Specters in the Past: The Saint Charles, Arkansas, Lynching of 1904 and the Limits of Historical Inquiry.” Journal of Southern History 65 (August 1999): 535–564.

Whayne, Jeannie M. A New Plantation South: Land, Labor and Federal Favor in the Twentieth-Century Arkansas. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996.

Wheeler, John M. “The People’s Party in Arkansas, 1891–1896.” PhD diss., Tulane University, 1975.

Williams, Johnny E. “Vanguards of Hope: The Role of Culture in Mobilizing African-American Women’s Social Activism in Arkansas.” Sociological Spectrum 24 (March/April 2004): 129–156.

Williams, Johnny E. African-American Religion and the Civil Rights Movement in Arkansas. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2003.

Woodruff, Nan Elizabeth. American Congo: The African American Freedom Struggle in the Delta. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003.

Zajicek, Anna M., Allyn Lord, and Lori Holyfield.“The Emergence and First Years of a Grassroots Women’s Movement in Northwest Arkansas, 1970–1980.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 62 (Summer 2003):153–181.

John A. Kirk

Royal Holloway

University of London

Arkansas Association of Colored Women

Arkansas Association of Colored Women Arkansas Civil Rights Act of 1993

Arkansas Civil Rights Act of 1993 Black Power Movement

Black Power Movement Civil Rights Movement (Twentieth Century)

Civil Rights Movement (Twentieth Century) Education Reform

Education Reform Great Migration

Great Migration Hodges v. United States

Hodges v. United States Jerome Relocation Center

Jerome Relocation Center Just Communities of Arkansas (JCA)

Just Communities of Arkansas (JCA) Lowery, Henry (Lynching of)

Lowery, Henry (Lynching of) Lucie's Place

Lucie's Place Multiculturalism

Multiculturalism Negro Boys Industrial School Fire of 1959

Negro Boys Industrial School Fire of 1959 Pharr, Suzanne

Pharr, Suzanne Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Right to Work Law

Right to Work Law Rohwer Relocation Center

Rohwer Relocation Center Rudd, Daniel

Rudd, Daniel United States v. Waddell et al.

United States v. Waddell et al. Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA)

Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) Urban Renewal

Urban Renewal Women's Library

Women's Library Young, Rufus King

Young, Rufus King Daisy Bates with Bill Clinton

Daisy Bates with Bill Clinton  Daisy Bates

Daisy Bates  BLM March

BLM March  John Bush

John Bush  Central High School Desegregation Commemorative Book

Central High School Desegregation Commemorative Book  Eldridge Cleaver

Eldridge Cleaver  Florence Cotnam

Florence Cotnam  Desegregation Protest at Capitol

Desegregation Protest at Capitol  Desegregation Protest at Capitol

Desegregation Protest at Capitol  Elizabeth Eckford Denied Entrance to Central High

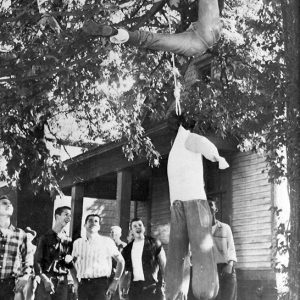

Elizabeth Eckford Denied Entrance to Central High  Effigy Hanging

Effigy Hanging  Elaine Massacre Newspaper Article

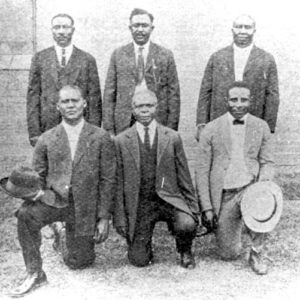

Elaine Massacre Newspaper Article  Elaine Massacre Defendants

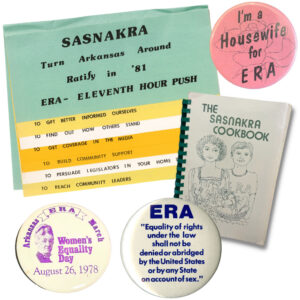

Elaine Massacre Defendants  ERA Ephemera

ERA Ephemera  Ernest Green

Ernest Green  Bill Hansen

Bill Hansen  Jim Crow Laws Cartoon

Jim Crow Laws Cartoon  Scipio Jones

Scipio Jones  Lena Lowe Jordan

Lena Lowe Jordan  Ku Klux Klan

Ku Klux Klan  Ku Klux Klan Rally

Ku Klux Klan Rally  Lest We Forget by Ben Shahn

Lest We Forget by Ben Shahn  Little Rock Nine Monument

Little Rock Nine Monument  Little Rock Nine Thanksgiving

Little Rock Nine Thanksgiving  John Gray Lucas

John Gray Lucas  Arrest of Bliss Anne Malone

Arrest of Bliss Anne Malone  Mosaic Templars Headquarters

Mosaic Templars Headquarters  National Guardsman Confronts Students at Central High

National Guardsman Confronts Students at Central High  Poll Tax Receipt

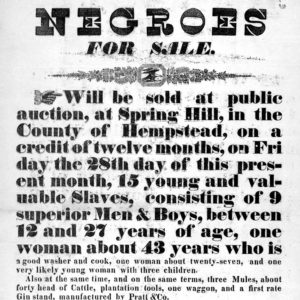

Poll Tax Receipt  Slave Auction Notice

Slave Auction Notice  Slavery Resolution

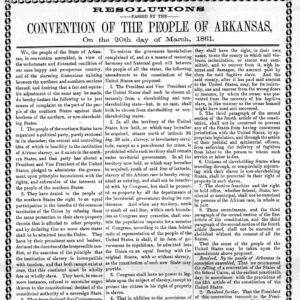

Slavery Resolution  Southern Tenant Farmers' Union

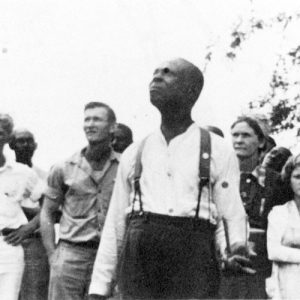

Southern Tenant Farmers' Union  Ozell Sutton

Ozell Sutton  Three of the North Little Rock Six

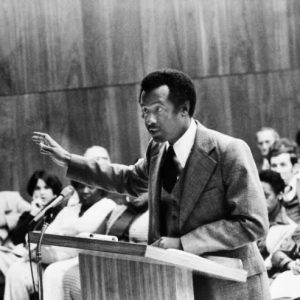

Three of the North Little Rock Six  John Walker

John Walker  WEC Members Brewer, Terry, and House

WEC Members Brewer, Terry, and House

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.