calsfoundation@cals.org

Red Scare (1919–1920)

aka: First Red Scare

In the United States, the First Red Scare (1919–1920) began shortly after the 1917 Bolshevik Russian Revolution. Tensions ran high after this revolution because many Americans feared that if a workers’ revolution were possible in Russia, it might also be possible in the United States. While the First Red Scare was backed by an anti-communist attitude, it focused predominately on labor rebellions and perceived political radicalism.

While Arkansas was not immune to the Red Scare, it did see comparatively little labor conflict. Nationally, 7,041 strikes occurred during the 1919–1920 period; Arkansas contributed only twenty-two of those strikes. This was not because Arkansas had a weak labor movement. In fact, Arkansas was home to the Little Rock Typographical Union, railroad unions, and sharecropper unions, among others. The lack of strikes was due in part to the positive labor legislation that existed in the state at that time. For example, in 1889, the state government forced railroad employers to pay wages in full to workers after they completed a day’s work. Laws such as this created a more progressive work environment for union workers—most of whom tended to be white, as non-whites were typically not allowed to join. Also, farms in Arkansas were generally small and family owned. While they did employ a system of sharecropping and tenant farming, most of the farms in Arkansas were too small to see the industrial strife that came with larger farms and big businesses across the rest of the country. Too, labor disputes in the agricultural sector, due to the prevalence of African Americans in the workforce, were easily racialized and, as a consequence, often brutally suppressed. A noteworthy example of this was the Elaine Massacre of 1919, during which members of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America were systematically killed and persecuted for attempting to resist labor exploitation.

Anti-Bolshevik Legislation

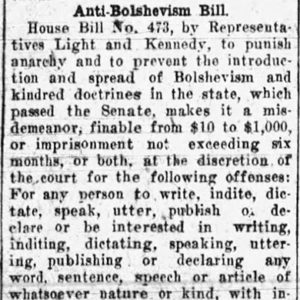

Though Arkansas did not exhibit the same level of labor conflict as the rest of the nation during the First Red Scare, it did follow the national trend of passing anti-Bolshevik or Criminal Anarchy laws.On March 28, 1919, Arkansas joined the majority of states in the union by passing Act 512, which read:

“An act to define and punish anarchy and to prevent the introduction and spread of Bolshevism and kindred doctrines, in the State of Arkansas.

§1. Unlawful to attempt to overthrow present form of government of the State of Arkansas or the United States of America.

§2. Unlawful to exhibit any flag, etc., which is calculated to overthrow present form of government.

§3. Laws in conflict repealed; emergency declared; effective after passage.”

Such a crime was a misdemeanor, punishable by a fine of between $10 and a $1,000, and the perpetrator could be imprisoned in the county jail for up to six months. This anarchy bill was originally introduced as House Bill Number 473, and, on March 6, 1919, it was read in the House of Representatives. The House moved that the bill be placed back upon second reading for the purpose of amendment. The motion was passed, and the following amendment was sent up: “Amend House Bill No. 473 by striking out the words ‘association of individuals, corporations, organization or lodges by any name or without a name,’ as found in lines 2 and 3 of section 2, of the bill.”

This amendment was suggested for the protection of labor unions. The bill was then placed on final passage. This bill passed the House with little opposition. Eighty-two legislators voted in the affirmative, and only one voted in the negative. Only forty-two votes were necessary to pass the bill, and with eighty-two affirmative votes, the bill was passed.

On March 12, 1919, House Bill 473 was read the third time and placed on final passage in the Senate. None voted in the negative, although ten were absent. There were twenty-five votes in the affirmative, with only thirteen necessary for the passage of the bill, and thus it passed. On March 28, 1919, Governor Charles Hillman Brough signed the bill, making it Act 512. Brough was a popular speaker at the time and spoke often of his dislike for Germans and radicals.

Criminal syndicalism laws were also commonplace during the First Red Scare. Criminal syndicalism addressed and punished acts of violence or acts of advocating violence as a means of bringing political change. Many of these laws were in response to the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, or Wobblies) and their attempts to organize minorities working in the fields. However, Arkansas was not one of the states that passed anti-syndicalism legislation.

Effects of Anti-Bolshevik Legislation

Though the First Red Scare ended in 1920, both the state and federal legislation passed during that time lasted much longer. These anti-Bolshevik laws were used against socialist, communist, and union organizers in Arkansas a number of times in the 1930s and in 1940. The Communist Party of Arkansas reached its peak in the 1930s. Some examples include the 1934 arrest of George Cruz, who was an activist involved in an organization called the Original Independent Benevolent Afro-Pacific Movement of the World (OIBAPMW); the 1935 arrest of Ward Rodgers, who was a member of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU); the 1935 arrest of Horace Bryan, a labor organizer; and the 1940 arrest of Nathan Oser, who was the director of Commonwealth College.

Due to some positive labor legislation that existed in the state, the rural isolation of many of the state’s citizens, and the focus on racial issues rather than ideological conflict, the scare in Arkansas did not turn into the hysteria felt by most of the rest of the nation, despite the anti-Bolshevik laws and resulting arrests.

For additional information:

Dowell, Elderidge Foster. A History of Criminal Syndicalism Legislation in the United States. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1939.

Franklin, F. G. “Anti-Syndicalist Legislation.” American Political Science Review 14 (1920): 291–298.

McCarty, Joey. “The Red Scare in Arkansas: A Southern State and National Hysteria.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 37 (1978): 264–277.

Kern, Jamie. “The Price of Dissent: Freedom of Speech and Arkansas Criminal Anarchy Arrests.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2012. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/475/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

Jamie Kern

Fayetteville, Arkansas

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Anti-Bolshevism Act

Anti-Bolshevism Act

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.