calsfoundation@cals.org

Thomas Dale Alford (1916–2000)

Thomas Dale Alford was a prominent Arkansas ophthalmologist, Episcopalian, radio announcer, civic leader, and politician remembered largely as a leader of opposition to federally mandated desegregation during the crisis at Central High School in Little Rock (Pulaski County). Alford’s role as a leading segregationist came first through his seat on the Little Rock School Board and then as the “Segregation Sticker Candidate” who upset incumbent Democratic U.S. Representative Brooks Hays after a notorious ten-day write-in campaign in the 1958 election for the Fifth Congressional District of Arkansas.

Dale Alford was born near Murfreesboro (Pike County) on January 28, 1916, the son of T. H. Alford and Ida Womack Alford, both of whom were itinerant school teachers. His father ultimately became one of the most prominent educators in the state’s history, serving as president of the Arkansas Education Association and then later as State Commissioner of Education under Governor Carl Bailey in the 1930s; in the 1950s, he served as superintendant of North Little Rock Schools and as principal of Jacksonville Public Schools, in which capacity he accepted hundreds of Little Rock public school students during the infamous “Lost Year” of 1958–59.

Dale Alford graduated from Rector High School at the age of sixteen during his family’s tenure in Clay County. He earned a BS from Arkansas State Teachers College (now the University of Central Arkansas) and, in 1939, graduated from the University of Arkansas Medical School (now the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences). While studying ophthalmology in medical school, Alford worked as a radio announcer for businessman and political leader Colonel Thomas H. Barton, hosting Pigskin Parade, which initiated the statewide fan base for the Razorbacks football team.

Alford married L’Moore Fontaine Smith of Sardis, Mississippi, on July 27, 1940. The couple had three children.

Following an internship at Saint Anthony Hospital in Oklahoma City and residency at the University of Illinois at Chicago, Alford served in the U.S. Army Medical Corps from 1940 to 1946, primarily in Europe. After World War II, Alford became one of the leading ophthalmologists of his generation, nationally recognized and widely respected within the medical profession. He briefly practiced in Atlanta, Georgia, while teaching at Emory University Medical School from 1947 to 1948, and then returned to Arkansas to establish a highly successful medical practice in Little Rock that catered to both white and black patients. Alford also served on the staffs of area hospitals and as a faculty member of his alma mater. He was active within professional circles, being named as a fellow of the American College of Surgeons, while taking leading roles within the American Medical Association, the Arkansas Medical Society, the International College of Surgeons, and the American Academy of Ophthalmology. His civic engagements included terms as president of both the Arkansas State Opera Company and the Little Rock Civitan Club, as well as membership in the American Legion, Disabled American Veterans, the Lions Club, and the Masons. He also served as senior warden of his church, where he expressed favorable views toward the desegregation of the Episcopal Diocese of Arkansas.

After his election to the Little Rock School Board in 1955, Alford quickly established a reputation as an intransigent segregationist. Alford was the only board member to oppose Superintendant Virgil T. Blossom’s desegregation plan and spoke out against any form of public school desegregation just before the arrival of the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division in September 1957. Alford further distanced himself from other board members when he publicly denounced their censure of Governor Orval Faubus in the summer of 1958. On September 26, 1958—the night before Little Rock voters were to consider a referendum on whether to close their schools rather than accept desegregation—Alford made a televised speech in which he endorsed privatized segregated education. He charged that desegregation was part of the international communist conspiracy, whereby black Southerners were used as propaganda pawns by communists in their ultimate quest to defeat the United States in the Cold War. Alford’s speech helped convince voters to approve the referendum.

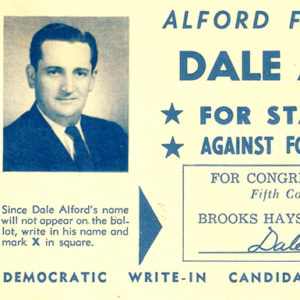

Alford decided to run for Congress in the 1958 general election as a write-in candidate after he received hundreds of letters of support for his opposition to desegregation, as well as a petition soliciting him to run against the increasingly unpopular Brooks Hays. Faubus’s aide, Claude Carpenter Jr., directed Alford’s write-in campaign. Alford, therefore, received the de facto endorsement of the popular governor, even though Faubus publicly distanced himself from the campaign.

Alford declared his candidacy on October 27, 1958, and quickly received key endorsements and support from prominent segregationist groups in the Fifth District. Although Hays never formally endorsed desegregation of public accommodations, Alford and Carpenter successfully portrayed the incumbent as the less militant segregationist. Carpenter bought three primetime television appearances for Alford to cover the district quickly. They also ran newspaper advertisements with a photograph of Hays worshiping with African Americans at a Baptist assembly under the headline “We Know You Brooks!” Thousands of flyers with this picture and caption were also anonymously dropped from an airplane on election day throughout the district.

On election day, Alford’s campaign staff distributed stickers and rubber stamps marked with his name and an “X” to every poll station in the district in order to make it easier for voters to write his name. Through the use of these stickers, Alford won the election with 30,739 votes to Hays’s 29,483, with an overwhelming majority in Pulaski County. Hays lobbied the U.S. Congress to investigate fraud in the election and declare his former congressional seat vacant, but the Democratic majority seated Alford as a regular member of the U.S. House of Representatives.

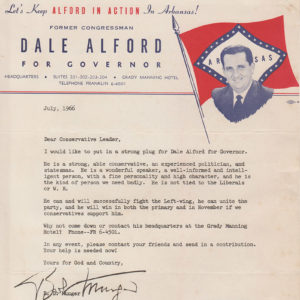

In 1959, Alford became a member of the Committee to Retain our Segregated Schools (CROSS), organized to continue the private school system in Little Rock. He won reelection to Congress in 1960, but redistricting thereafter placed him in the same congressional district as the formidable Democratic U.S. Representative Wilbur Mills, whose segregationist credentials were beyond reproach. Alford decided to run for governor in 1962, a race he lost. In 1966, he also failed in a second attempt to win the Democratic nomination for governor. After he left the U.S. House of Representatives, Alford resumed both his medical practice and his active civic life. In 1984, Alford made one final attempt to win the now Second District congressional seat but finished last among five candidates in the Democratic primary.

Alford died on January 25, 2000, of congestive heart failure and is buried in Little Rock’s Mount Holly Cemetery. The legendary Arkansas financier Witt Stephens summed up Alford’s impact on state politics with the quip that the ophthalmologist-turned-politician was like a wasp: “When he is first born, he is bigger than he will ever be again.”

For additional information:

Alford, Dale, and L’Moore Alford. The Case of the Sleeping People. Little Rock: Pioneer, 1959.

———. The Constitutional Crisis: Its Threat to the Liberty and its Remedy. New York: R. Speller, 1960.

Ault, Larry. “Alford, Write-in House Winner of Central Era, Dies.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. January 27, 2000, pp. 1A, 5A.

Day, John Kyle. “The Fall of Southern Moderation: The Defeat of Brooks Hays in the 1958 Congressional Election for the Fifth District of Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 1999.

———. “The Fall of a Southern Moderate: Congressman Brooks Hays and the Election of 1958.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59 (Autumn 2000): 241–264.

Johnson, Ben F., III. Arkansas in Modern America since 1930. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2019.

John Kyle Day

University of Arkansas at Monticello

Alford, Boyce

Alford, Boyce Health and Medicine

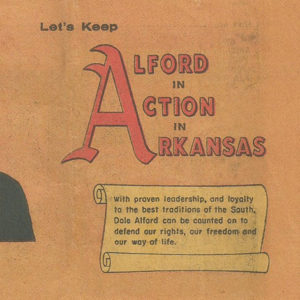

Health and Medicine Alford Campaign Comic

Alford Campaign Comic  Alford Support Letter

Alford Support Letter  Dale Alford

Dale Alford  Alford Campaign Headquarters

Alford Campaign Headquarters  Thomas and L'Moore Alford

Thomas and L'Moore Alford  Thomas Alford

Thomas Alford

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.