calsfoundation@cals.org

National Grange of the Order of the Patrons of Husbandry

aka: The Grange

aka: Arkansas State Grange

aka: Patrons of Husbandry

In December 1867, Oliver Hudson Kelley, a former clerk in the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and six other men founded the National Grange of the Order of the Patrons of Husbandry in Washington DC. Intended as an organization that would unite farmers for the advancement of their common interests, the Grange claimed more than 760,000 members across the United States by 1875. The Grange entered Arkansas in 1872 and remained active in the state for about two decades. By then, the Grange had given way to larger farmers’ organizations in Arkansas such as the Agricultural Wheel and the Farmers’ Alliance. The National Grange still exists in the twenty-first century, but it has no chapters in Arkansas.

Origins, Growth, and Purposes

John Thompson Jones, a politically prominent planter who lived near Helena (Phillips County), served as the pioneer and first leader of the Granger movement in Arkansas. In June 1872, Jones contacted Kelley for information about forming local Grange chapters and a state organization. By August 1872, Jones had organized Arkansas’s first local Grange chapter, consisting of nine men (including himself) and five women. In June 1873, delegates from the state’s fifteen local Grange chapters met in Helena and founded the Arkansas State Grange.

The National Grange published a Declaration of Purposes in February 1874 that identified middlemen and monopolists as the economic enemies of farmers, urged farmers to engage in crop diversification and economic cooperation, and declared the Grange to be nonpartisan. The Declaration of Purposes received considerable press coverage in Arkansas and nationally, and by October 1875, the Arkansas State Grange claimed 20,471 members (apparently all white) in 631 local chapters. By October 1876, the Arkansas State Grange had combined with its counterparts in Tennessee, Louisiana, and Mississippi to form the Southwestern Co-operative Association, based in Memphis, Tennessee, which established and operated cooperative stores across those four states but, like many Grange cooperative enterprises, proved short-lived.

Politics

As was true in most late-nineteenth-century farmers’ organizations, not all members of the Grange respected the organization’s official position of nonpartisanship. In Arkansas, Simon P. Hughes, who served as the Worthy Master of the State Grange from 1877 to 1879, drew upon Grange support in his unsuccessful bid for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination in 1876; he sought that nomination again in 1878 and finally won election to the governor’s office in 1884, but by 1878 the Grange had declined so sharply in Arkansas that it no longer maintained enough members to be a political force. Other prominent Arkansas Grangers, such as Charles E. Tobey of Pope County and Charles E. Cunningham of Little Rock (Pulaski County), became actively involved in the Greenback Party as well as later third-party efforts, and many of the votes that Greenback candidates received in Arkansas during the late 1870s and early 1880s probably came from men who had been members of the Grange.

Demise and Legacy

By July 1876, the reported membership of the Arkansas State Grange had plummeted by forty-five percent (to 11,344) in a mere ten months, and by the end of the decade, the organization had waned almost to the point of obscurity, although it remained active until being absorbed by the Arkansas Farmers’ Alliance in the early 1890s. The Grange’s demise in Arkansas probably stemmed from its inability to solve farmers’ economic problems—as typified by the failure of the Southwestern Co-operative Association—and partisan strife that arose within the organization during the political campaigns of 1876. Nevertheless, the Grange made a significant impact in Arkansas, introducing better methods of farming to thousands of farmers and facilitating social and recreational activities for them as well. The Grange also helped pave the way for larger farmers’ organizations that would soon become active in Arkansas, such as the Brothers of Freedom, the Agricultural Wheel, and the Farmers’ Alliance, as well as the independent and third-party political movements that challenged the Democratic Party in the state from the 1870s through the 1890s, most notably the Greenback Party, the Union Labor Party, and the Populist Party.

For additional information:

Barjenbruch, Judith. “The Greenback Political Movement: An Arkansas View.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 36 (Summer 1977): 107–122.

Davis, Granville D. “The Granger Movement in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 4 (Winter 1945): 340–352.

Hild, Matthew. Greenbackers, Knights of Labor, and Populists: Farmer-Labor Insurgency in the Late-Nineteenth-Century South. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007.

Nordin, D. Sven. Rich Harvest: A History of the Grange, 1867–1900. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1974.

Saloutos, Theodore. “The Grange in the South, 1870–1877.” Journal of Southern History 19 (November 1953): 473–487.

Matthew Hild

Georgia Institute of Technology

Agriculture

Agriculture Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

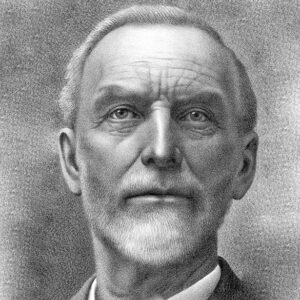

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Charles E. Cunningham

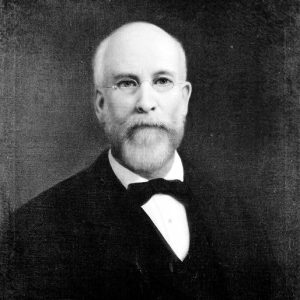

Charles E. Cunningham  Simon Hughes

Simon Hughes

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.