calsfoundation@cals.org

St. Charles Lynching of 1904

Over the course of four days in the first week of spring 1904, a succession of white mobs terrorized the black population of St. Charles (Arkansas County). They murdered thirteen black males in this town of about 500. Given the death toll, it was one of the deadliest lynchings in American history. The murderers were never identified in either public reports or eyewitness accounts, and the scant surviving evidence in newspapers and manuscripts lists only the victims, not the killers or their possible motives.

On Monday, March 21, on the dock at the White River crossing in St. Charles, Jim Searcy, a white man, argued over a game of chance with a black man named Griffin, with whom he was gambling. The disagreement escalated to blows. A policeman arrested Griffin for assault and informed the black man that he was about to be hanged. Griffin struck the officer, grabbed his gun, and fled.

Griffin went into hiding, but angry white mobs were determined to find him. Whites summoned from surrounding towns and the countryside arrived from DeWitt (Arkansas County), Clarendon (Monroe County), Ethel (Arkansas County), and Roe (Monroe County). On the afternoon of Wednesday, March 23, whites on horseback roamed the countryside, accosting black citizens on sight. Those who resisted were shot. Between sixty and seventy black men, women, and children were driven from their homes and fields and then penned into a warehouse. That night, white mobs around the structure demanded to torch the building and burn all the black people imprisoned inside it. As a white witness later testified to the mob’s intent, “[T]hey wanted to exterminate the negro race.” According to a manuscript source, leaders of the mob insisted on restraint. Some of the rioters began to plead for “special negroes” who should be spared. Others urged caution on behalf of the good name of the town of St. Charles.

Around 3:00 in the morning of Thursday, March 24, the whites stormed the building, took six black men from the scores of captives, and marched them to the high point on the highway from St. Charles to DeWitt, the county seat. They made the men stand in a line and then shot them dead.

On Sunday, March 27, the Arkansas Gazette, in the most detailed coverage of the killings, published a list of the dead men: Abe Bailey, Mack Baldwin, Will Baldwin, Garrett Flood, Randall Flood, Aaron Hinton, Will Madison, Charley Smith, Jim Smith, Perry Carter, Kellis Johnson, Henry Griffin, and Walker Griffin; the man originally arrested and his brother were murdered on Saturday. The Griffins bring the number killed to thirteen.

If the killings at St. Charles are viewed as a single episode, with a body count of thirteen, then the incident is one of the single deadliest mass lynchings in American history. But for a homicide to qualify as lynching, according to the standard scholarly definition of lynching, a minimum of three perpetrators had to participate in each murder—it is in that sense that lynching is a public event. Because the number of murderers associated with each killing in St. Charles remains unknown, some of the fatalities may not be classified as victims of lynching.

For additional information:

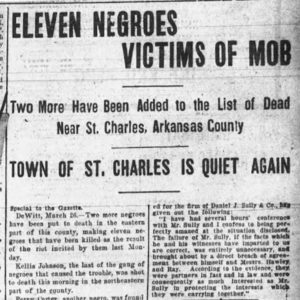

“Eleven Negroes Victims of Mob.” Arkansas Gazette. March 27, 1904, p.1.

Hennigan, Mary. “The Arkansas Racial Massacre Almost No One Remembers.” Howard Center for Investigative Journalism, December 13, 2021. https://lynching.cnsmaryland.org/2021/12/12/incomplete-coverage-of-1904-st-charles-arkansas-massacre-leaves-gap/ (accessed December 13, 2021).

———. “Media Erasure: A 1904 Lynching in St. Charles, Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2022.

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889–1918. New York: Arno Press, 1969.

“13 Negroes Were Slain: Wholesale Killing Occurred in Arkansas Co. Race War Last Week.” Arkansas Democrat. March 29, 1904, p. 5.

Vinikas, Vincent. “Specters in the Past: The Saint Charles, Arkansas, Lynching of 1904 and the Limits of Historical Inquiry.” Journal of Southern History 65 (August 1999): 535–564.

Vincent Vinikas

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

St. Charles Lynching Article

St. Charles Lynching Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.