calsfoundation@cals.org

Treaty of Council Oaks

On June 24, 1823, Acting Governor Robert Crittenden of Arkansas Territory met with a group of Arkansas Cherokee; the place of their meeting been described in many sources on the south side of the Arkansas River in the vicinity of modern Dardanelle (Yell County), though this is debatable, as the agent for the Cherokee, Edward W. DuVal, was likely headquartered north of the river, the land south of the river having been reserved for the Choctaw. The leaders present included John Jolly (who was likely the most influential member of the group and would soon be elected principal chief of the Arkansas Cherokee), Black Fox, Wat Webber, Waterminnow, Young Glass, Thomas Graves, and George Morris. Each group came to the meeting with a different agenda, and neither group left the meeting satisfied. Both parties subsequently pressed their cases in writing to Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, who at the time had supervisory authority over Indian affairs throughout the country.

Although this meeting is referred to as the “Treaty of Council Oaks,” it was actually not a treaty-making event. Crittenden, who did not in any event have the authority to initiate treaties with Indian tribes on behalf of the U.S. government without direction from Washington DC, supported the popular desire among non-Indians in the territory to see all Indian lands opened for white settlement and all tribes removed from the territory as soon as possible. In 1823, a large portion of northwest Arkansas, including the north bank of the Arkansas River from Point Remove to an uncertain point near Fort Smith (Sebastian County) and northeastward to the south bank of the White River, was Arkansas Cherokee land. In addition, a second tract, referred to as Lovely’s Purchase, upstream from Fort Smith, was intended as an outlet for Arkansas Cherokee to travel in safety west to the game-rich grasslands. A nearly equal portion of Arkansas territory between the Cherokee lands and the Red River had been given to the Choctaw in 1820 in anticipation of their removal from homelands in Mississippi to lands in Arkansas. Although the Choctaw had repudiated the treaty, this tract remained theirs even though no Choctaw people resettled within it. Instead, more than 1,000 Cherokee, and an unknown number of whites, squatted south of the Arkansas River and along the lower reaches of tributary creeks.

The 1817 treaty establishing the Arkansas Cherokee reservation described the intended boundaries and linked the size of the reservation to the area surrendered by the Cherokee back east. Although a boundary survey and demarcation had been carried out early in 1819, Arkansas Cherokee were unsatisfied with the reservation size and shape. They felt that the written description of the tract on which the survey had been based had shortchanged them, and they wished the boundaries to be re-drawn. One important issue was the Cherokee desire to maximize the amount of alluvial valley land within the reservation by formalizing the west boundary of the reservation parallel to the east boundary, thereby including a maximum amount of land along the north bank of the Arkansas River. In addition, the Cherokee felt that the acreage within the reservation described in the treaty was less than the amount they had negotiated for in 1817.

Crittenden wished to minimize lands under Indian control, and he was looking for leverage useful for hastening the removal of Indians from the territory. He informed the Cherokee leaders that the boundary had to be drawn according to the written treaty descriptions.

Another lingering issue with both territorial and federal authorities was the presence of Cherokee settlers south of the Arkansas River on rich farmland highly desirable to white settlers. At first, this land was potentially available for purchase and settlement, but in 1820 it became Choctaw land, and the U.S. government ordered all squatters removed. Crittenden felt that it would be easier for the U.S. government to rescind the Choctaw Reservation south of the Arkansas River if the Cherokee could be removed from the land. He informed the Cherokee that some of their members were living illegally south of the River and that he had the authority to have them removed to reservation land on the north bank. No doubt to Crittenden’s surprise, the Cherokee responded that neither the territorial nor the U.S. government had any say in whether they lived south of the river, because it was Choctaw lands and the Choctaws did not care if the Cherokee lived there. This situation held true until December 1824, when a Choctaw delegation that had traveled to Washington DC agreed to a treaty redrawing the boundaries of their lands west of the Mississippi River and doing away with the reservation tract in Arkansas Territory.

As the Dardanelle meeting drew to a close, the Cherokee leaders dictated a letter to Secretary of War Calhoun describing their concerns, had Crittenden sign it in their presence, and then gave it to him to send on to Washington DC. After a three-month delay, Crittenden sent the letter along with one of his own to Calhoun. Crittenden related his interpretation of the Dardanelle meeting events and reiterated his arguments on behalf of territorial citizens that the Cherokee, Choctaw, Quapaw, as well as a number of newly arrived Indian groups residing in the upper White River region, be removed as soon as possible.

The Arkansas Cherokee were unable to secure changes in their reservation boundary and were equally frustrated in attempts to get guarantees and clarification of the tribe’s clear control of their lands. In 1826, the U.S. government opened the Lovely Purchase tract to white settlement without consulting the Cherokee. These were two factors, among many, that led to the 1828 treaty in which the Arkansas Cherokee surrendered their Arkansas land for a new tract in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). When the western boundary of Arkansas was finally surveyed, however, a majority of the Lovely Purchase land remained in Indian Territory and fell under Indian control. Crittenden and his supporters got most of what they were hoping from the meeting in Dardanelle, but years later than the event and as a result of subsequent events.

The meeting held between the Arkansas Cherokee and Crittenden in 1823 was a notable diplomatic event between the Cherokee and territorial authorities, even if it did not answer the needs of either party at the time. Today, some Dardanelle residents believe that an old oak tree situated near the Arkansas River marks the setting of this encounter.

For additional information:

Bolton, S. Charles. “Jeffersonian Indian Removal and the Emergence of Arkansas Territory.” In A Whole Country in Commotion: The Louisiana Purchase and the American Southwest, edited by Patrick G. Williams, S. Charles Bolton, and Jeannie M. Whayne. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. 2005.

Carter, Clarence Edwin, ed. The Territorial Papers of the United States. Vol. 19, The Territory of Arkansas, 1819–1825. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1953.

Ann M. Early

Arkansas Archeological Survey

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860 Council Oaks Tree

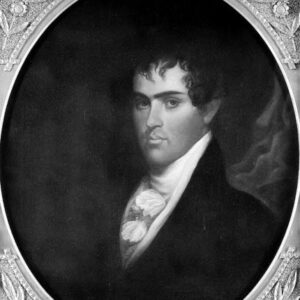

Council Oaks Tree  Robert Crittenden

Robert Crittenden

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.