calsfoundation@cals.org

Philanthropy

Nonprofit and volunteer organizations in Arkansas, from religious groups in the territorial period to the charitable foundations of today, have contributed greatly to the economic wellbeing of the state. Charitable giving by private groups to benefit persons outside their own membership—the definition of philanthropy used here—has been an essential feature of the economic landscape of Arkansas. This has been the case because of the state’s long-term experience with poverty and with a reluctance, until fairly recently, to use government programs to alleviate human suffering and expand educational opportunities for the people of Arkansas.

Rise of Organized Philanthropy

Organized charitable giving first grew out of church, women’s, and fraternal groups. In the absence of state-sponsored educational institutions, churches in pre–Civil War Arkansas focused most of their charitable efforts on the establishment of schools and colleges. Organized religion sought to administer elements of social stability where possible, through such efforts, for example, as the Dwight Mission among the Cherokee by Presbyterian missionaries in 1820, which provided some rudimentary educational opportunities, as well as the creation of church buildings that represented significant investments at the time. But aside from schools, which were essentially extensions of evangelistic efforts, churches provided little in the way of systematic charitable efforts toward disadvantaged people.

Chronic poverty and the lack of charitable assistance to deal with it caused many social problems for the state. In the years leading up to the Civil War, poverty only worsened. Between 1850 and 1860, the number of people officially defined as “paupers” in Arkansas almost tripled. The Civil War brought further economic hardship to the state’s disadvantaged people and to the private institutions that were trying to serve public needs. The struggles of pre–Civil War colleges founded by churches, such as Cane Hill College (founded by Cumberland Presbyterians) and Arkansas College (founded by Disciples of Christ)—both in Washington County—and St. Johns’ College in Little Rock (Pulaski County), showed the good intentions but limited resources of church and fraternal organizations. Of the more than 100 academies and colleges founded between 1849 and 1861 in Arkansas, only a few reopened briefly after the Civil War; most never reopened at all. In a move that foreshadowed post–Civil War actions, missionary organizations raised money from Northern benefactors and sent teachers and funds to Arkansas to create schools for former slaves, even prior to the end of the war. The Town Colored School in Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), which opened in November 1864, grew out of the Home Farm School, which began the previous February.

After the war, Arkansas received financial and volunteer help from former abolitionists, as individuals and as members of organizations, who became involved in various parts of the former Confederacy as part of the general Northern spirit of Reconstruction of the South. Within thirty years of the war’s end, Northern philanthropists had sent an estimated $15.7 million to Southern states, including Arkansas, mainly to provide educational opportunities for freed slaves and their families. The American Missionary Association contributed $6 million; the Freedman’s Aid Society (Methodist), $2.2 million; the Baptist Home Mission, $2 million; the Presbyterian Home Mission, $1.5 million; women’s societies, the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and other groups, $1 million; and individual donors, a total of $3 million.

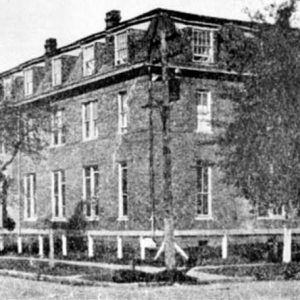

Religiously affiliated institutions of higher education founded after the war fared better on the whole than those begun before the war as church sponsorship increasingly involved regular appropriations of funds. Among schools for African Americans, the most enduring were Southland College, founded in 1864 by Quakers; Philander Smith University, founded in 1883 by the Freedman’s Aid Society (Methodist); Arkansas Baptist College, founded in 1884 by the Negro Baptist State Convention of Arkansas; and Shorter College, founded in 1886 as Bethel University by the Arkansas Conference of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Southland College closed in 1925, but the others are still operating. Church-affiliated colleges that began as all-white institutions in the first decades after the Civil War included Arkansas College (now Lyon College), which was founded by Presbyterians in 1872; Hendrix College, founded in 1876 by Methodists; and Ouachita Baptist College (now Ouachita Baptist University), founded in 1886 by Baptists.

As in most of the South, banking and other financial institutions in Arkansas remained weak in the Reconstruction era, so it was difficult to generate sufficient business activity and tax revenue to fund public institutions. Additionally, state spending on education and public welfare had always been low because of philosophical objections to spending large amounts of state money on education and social problems, along with a persistent opposition to increased taxes. To make matters worse, the state legislature passed a law in 1871 that severely limited the ability of local governments to tax their citizens to provide sufficient funding for extensive public schooling. The result of that legislation was that only about one tenth of the school districts of Arkansas were able to keep schools open for as much as three months a year. Private individuals and organizations in Arkansas were unable to fill the gaps in funding created by such public policies.

As business activity developed in the Gilded Age—the years between the end of Reconstruction and the end of the nineteenth century—new opportunities appeared for office workers and mid-level managers, and a stronger middle class arose. Also, the “social gospel” movement and other reform efforts ushered in a number of progressive initiatives in U.S. society, and civic groups in Arkansas sought to follow national trends toward using the growing wealth of the middle class to bring about social improvement. Arkansas’s approach to philanthropy began to change, especially with regard to the increased involvement of women’s and church organizations in assistance to the poor and other services intended to help provide the means for poorly educated, low-income persons to be more successful and economically secure.

Increasing numbers of women in Arkansas combined evangelical impulses, temperance activism, and advocacy of voting rights for themselves at various times during the nineteenth century, but as the century came to a close, they became particularly interested in social “uplift” for the poor, helping them find a place on the economic ladder that many believed led to the fulfillment of the American Dream. To help coordinate their efforts, whites-only women’s groups in the state founded the Arkansas Federation of Women’s Clubs (now the General Federation of Women’s Clubs of Arkansas) in 1897. Delegates at the first conference included, among others, the Pacaha Club of Helena (Phillips County), the Mothers’ Half Hour Club of Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), the Woman’s Cooperative Association of Searcy (White County), and the Woman’s Library Association of Van Buren (Crawford County), as well as various chapters of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), which had begun a chapter in Arkansas in 1879. African-American women formed their own groups to raise money to provide for the basic needs of destitute former slaves.

Many middle-class business leaders in Arkansas formed local chapters of national civic groups. These organizations, such as the Rotary Club of Helena, which began in 1905, engaged in unified charitable aid in Arkansas communities. The Rotary Club of Little Rock performed its first public charitable act in the fall of 1915 with a gift of $8,000 to the United Charities. The next year, the organization gave shoes, stockings, and bags of candy and fruit to 108 underprivileged children. The Lion’s Club of Little Rock was organized in 1916 and the Kiwanis Club in 1919, the same year the Lion’s Club and the Rotary Club of Jonesboro formed. In 1927, the Young Business Men’s Association came into being in Little Rock for the purpose of “civic betterment.”

Organized charitable giving in the 1910s and 1920s received a boost from the 1917 U.S. Revenue Act, which enabled taxpayers to deduct a portion of charitable gifts from their income taxes, especially to encourage giving during the country’s participation in World War I. Additionally, noteworthy organizations devoted to the encouragement of charity in Arkansas included the American Association of Societies for Organizing Charity and the Charity Organization Department of the Russell Sage Foundation. The chief aim of the charities at this time was “the rehabilitation of families in distress,” focusing especially on widows with children, deserted wives with children, families in which the wage earner had tuberculosis, single women with children, low-income married couples with children, and homeless men.

Reformers attempted to pressure state and local governments to aid the poor, especially children, usually with little effect. Help for disadvantaged African Americans was particularly lacking. In the last two decades of the nineteenth century and first two decades of the twentieth, most black children in Arkansas had few schools to attend. In 1910, only fifty-eight percent of black elementary-age children attended schools. Of those attending, only four percent received instruction in relatively better-run private schools.

On the other hand, private organizations in the state attempted to aid African Americans. The Mosaic Templars of America (MTA), a black fraternal organization, arose in Little Rock in 1892 and spread to more than half of the United States and a number of other countries, providing its members with various services but also serving the needs of the black population in general by encouraging self-help measures. The state’s Prince Hall Masons began an endowment to aid African Americans during this period, and more than twenty private schools for black students were begun by Northern philanthropists and African Americans in Arkansas. Arkansas chapters of the National Association of Colored Women organized and funded self-help and social-welfare efforts for low-income African Americans in the state.

The disastrous Flood of 1927 demonstrated the inability of state-based charities, as well as state and federal government, to deal with massive economic disruption and human loss. Most of the burden of response to the flood fell on the national Red Cross organization and its affiliates in Arkansas, as it did during an almost equally disastrous drought beginning in 1930. Still, civic groups participated in increasingly visible charity. Following the Arkansas legislature’s 1939 bill whereby blind people were given the opportunity to operate vending stands inside government buildings, the Little Rock Lions International contributed $2,500 for the first vending stands. This action led directly to the establishment of the Lions’ Southwest Rehabilitation Center (now Lions World Services for the Blind) in 1947 for job training for the blind in Little Rock.

Rise of the Foundations

Far and away, however, foundations performed the greatest philanthropy. In the period between the Civil War and World War I, great industrial fortunes were made in the northern United States, frequently generating well-funded foundations to perform charitable work in the name of the industrial philanthropists. Few such foundations arose in the South during this period, Arkansas included, because the wealth that created them in the North was not as great in the South. Industrialization had come to Arkansas through railroads, the timber industry, and a general economic trend toward a less agriculturally based economy. But Arkansas’s version of the fortunes that built the great national foundations did not develop until the post–World War II period, rising with the tide of national prosperity that accompanied wartime spending and postwar development.

Prior to the formation of philanthropic foundations in Arkansas, several well-known national foundations funded nonprofit causes in the state. For instance, although Andrew Carnegie gave money to numerous public libraries, beginning with those in Fort Smith (Sebastian County) and Little Rock in 1906, and paid for church organs in Arkansas as a private individual, the Carnegie Corporation (founded in 1911) made its first grant to an Arkansas institution, the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County), in 1930. In 1913, John D. Rockefeller’s Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease sponsored a conference in Little Rock on eliminating the disease in the South, the same year as the founding of the Rockefeller Foundation, before the commission’s absorption into the foundation in 1915. UA received the state’s first Rockefeller Foundation grant in 1950. One of the most significant out-of-state donors to projects in Arkansas has been the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation, headquartered in Las Vegas, Nevada; this foundation was based upon the fortune Donald W. Reynolds had built in part through newspaper and advertising enterprises in Arkansas. The foundation has given hundreds of millions of dollars for construction projects at numerous Arkansas institutions, especially those devoted to higher education, including the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS).

By the end of the twentieth century, personal, family, and corporate foundations in Arkansas had matured to the point that they were making sizeable contributions to nonprofit efforts in Arkansas. They also somewhat reversed the former flow of philanthropic dollars from foundations outside Arkansas into the state by making gifts to organizations outside of Arkansas. Many of the state’s leading foundations made significant grants both within and outside Arkansas to educational, healthcare, and social-welfare institutions. The state’s largest foundation, according to 2005 reports (which also provided the following figures), both in assets and giving was the Walton Family Foundation, with $1.3 billion in assets—half the total of all Arkansas foundations—and gifts totaling $157 million. The foundation, established by Sam Walton and wife Helen Walton, was based on the fortune generated by Walmart Inc. The company itself also created a foundation, whose giving is sometimes supplemented by funds raised from customers for specific projects. The Wal-Mart Foundation was second among Arkansas foundations in giving in 2005, with $155 million dispensed, though it ranked seventeenth in the state in total assets with $18.8 million because of its practice of dispersing more of its total funds than foundations do ordinarily. The Walton family also supports the Walton Family Charitable Support Foundation, which ranked eleventh in gifts. The Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation, named for the former Arkansas governor and grandson of John D. Rockefeller, had assets of almost $140 million, ranking second in the state, and gifts of almost $7 million, ranking fifth. A separate Rockefeller-funded charity, the Winthrop Rockefeller Trust, was third in assets and sixth in giving. The Charles A. Frueauff Foundation ranked fourth in assets and eighth in giving. The Arkansas Community Foundation was fifth in Arkansas in assets and seventh in giving, followed by the Ross Foundation, sixth in assets; the Walton Family Charitable Support foundation, seventh in assets; the Harvey and Bernice Jones Center for Families, eighth in assets; the Murphy Foundation, ninth in assets; and the Windgate Charitable Foundation, tenth in assets.

Founded in 1976, the Arkansas Community Foundation represented a new approach for the state’s philanthropic efforts, one seeking to stimulate giving around the state through the creation of local and regional endowments to support nonprofit efforts. Created with a Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation gift of $258,000, the Arkansas Community Foundation attracted gifts from individuals and from other foundations, including $19 million in matching gifts from the Walton family. As a public charity, the Arkansas Community Foundation receives charitable gifts from individuals, other nonprofit organizations, and corporations. By the time of its thirtieth anniversary, it had become both a grant-making organization and a network of affiliated entities in thirty-three Arkansas counties, creating endowments for charitable purposes in partnership with local benefactors. The foundation is especially involved in promoting planned giving whereby people can put provisions in their wills for some or all of their estate to go into funds for charitable giving, especially endowments whose investment income will be spent, preserving the principle of the original gift. The foundation also works with youth advisory groups around the state to encourage future generations of philanthropists.

Along with the work of the foundations in Arkansas, the state’s charitable involvements brought it attention at the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first. Arkansas became noted not only as a charitable state but also as the home base of a number of nationally and internationally prominent charitable organizations. Between 1997 and 2004, Arkansas consistently was ranked among the top seven states in individual charitable contributions while being among the five least wealthy states. Additionally, nonprofit groups in Arkansas performed large-scale charitable work on behalf of others, with hunger relief a special concern for Arkansas philanthropies. Heifer Project International, headquartered in Little Rock, operates in dozens of countries to eliminate the threat of starvation by enabling low-income people throughout the world to feed themselves on a sustained basis. Potluck Food Rescue for Arkansas is an organization that redirects otherwise wasted food to low-income persons in Arkansas and organizations that serve them. Arkansas Foodbank Network and Arkansas Rice Depot, among other organizations, work to relieve hunger and malnutrition.

Arkansas’s philanthropic past has always paralleled the state’s development. When the state’s economic fortunes suffered, philanthropy was also slow to develop. As the economy matured, diversified, and became more globally connected, the state’s philanthropic efforts not only grew but also became nationally and internationally significant. Charities benefited from the state’s growing prosperity, but they also contributed to it by helping create a healthier, better-fed, better-educated population, essential for the state’s continued advancement.

For additional information:

“Arkansas Community Foundation Turns 30.”Arkansas Times, November 9, 2006, pp. 14, 16.

Ettling, John. The Germ of Laziness: Rockefeller Philanthropy and Public Health in the New South. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981.

Hanger, Frances Marion. History of the Arkansas Federation of Women’s Clubs, 1897–1934. Van Buren: Arkansas Federation of Women’s Clubs, 1935.

History of Philanthropy Collection. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Jones, Thomas Jesse. Negro Education: A Study of the Private and Higher Schools for Colored People in the United States. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1917.

Kennedy, Thomas. “Southland College: The Society of Friends and Black Education in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 42 (Autumn 1983): 207–238.

Kittler, Glenn D. The Dynamic World of Lions International: The Fifty-year Saga of Lions Clubs. New York: M. Evans, 1968.

Knight, Edgar Wallace. Public Education in the South. New York: Ginn and Co., 1922.

McDonald, Erwin L. Sixty Years of Service: History of the Rotary Club of Little Rock. Little Rock: Rotary Club of Little Rock, 1974.

Minton, Mark. “Charitable Foundations in Arkansas Robust, Donating Millions of Dollars.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. January 9, 2005, pp. 1A, 12A.

———. “Foundations’ Contributions Hit New High in Arkansas.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. January 14, 2007, pp. 1A, 12A.

Otken, Charles H. The Ills of the South: or, Related Causes Hostile to the Prosperity of the Southern People. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1894.

Pearce, Larry Wesley. “The American Missionary Association and the Freedmen in Arkansas, 1863–1878.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 30 (Summer 1971): 123–144.

Pratt, Erin C. “Walmartland: Music and Corporate Philanthropy in Northwest Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2019.

Southern Sociological Congress, and James E. McCulloch. The South Mobilizing for Social Service: Addresses Delivered at the Southern Sociological Congress, Atlanta, Georgia, April 25–29, 1913. Nashville, TN: Southern Sociological Congress, 1913.

Works Projects Administration. A Directory of Civilian Organizations in the State of Arkansas, 1942. Little Rock: Historical Records Survey, 1942.

David Stricklin and Chris Stewart

Butler Center for Arkansas Studies

Ben Altheimer

Ben Altheimer  Arkansas Community Foundation Former Headquarters

Arkansas Community Foundation Former Headquarters  Harvey Couch with Will Rogers

Harvey Couch with Will Rogers  Fred Darragh

Fred Darragh  Heifer Project International World Headquarters

Heifer Project International World Headquarters  Sarah Elizabeth Mitchell

Sarah Elizabeth Mitchell  Gus Ottenheimer

Gus Ottenheimer  Donald Reynolds

Donald Reynolds  John D. Rockefeller and John D. Rockefeller Jr.

John D. Rockefeller and John D. Rockefeller Jr.  Win Rockefeller

Win Rockefeller  Shorter College

Shorter College

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.