calsfoundation@cals.org

Recreational and Retirement Communities

Land developers have long capitalized on the American dream of owning real estate or a home in the sun by mass-marketing vacation and retirement home sites to a distant clientele. Land was subdivided into relatively small lots within amenity-based subdivisions and sold as future retirement home sites or as an investment. During the 1950s, property in suburban subdivisions became popular. Lots were mass-marketed by a few large land development corporations, principally in Florida, Texas, Arizona, and California. The companies created a nationwide market for property sold on the installment plan by mail, often sight unseen. This type of land development soon became a national phenomenon; raw or partially developed acreage was “improved,” subdivided into small parcels, and offered for sale on liberal terms. From this boom was born the present-day recreational land development industry.

Sales of vacation and retirement home sites in recreational subdivisions totaled more than $5 billion a year in the United States in the early 1970s. A large market and high profit margin prompted some of the nation’s largest corporations, such as AT&T and General Acceptance Corporation (GAC), to enter the installment land sales business. The most successful companies and their stockholders reaped very large profits. Unfortunately, most of the customers, representing people from all walks of life, did not share in these benefits. High-pressure sales tactics by unscrupulous developers primarily interested in generating profits from sales of raw land produced thousands of virtually uninhabited subdivisions across the United States.

Major recreational land development activities began in Arkansas by the early 1900s. These activities all but disappeared during the Depression and did not reemerge in a substantial manner until the 1950s. This most recent and significant round of retail land sales activity began in Arkansas at Diamond Acres (Boone County) along Bull Shoals Lake and Cherokee Village (Sharp County) west of Hardy (Sharp County). Cherokee Village, the state’s first major amenity-oriented subdivision, was the first of several large recreational and retirement communities created by Cooper Communities, Inc.

Although Arkansas is not among the leading land development states, it has hundreds of small recreational subdivisions and thirteen projects that exceed 1,000 acres in size. The state ranks tenth among the fifty states in the total number of lots within amenity-based subdivisions. The largest subdivisions, those that exceed 1,000 acres, are found in clusters across the Ozark Mountains of northern Arkansas and in the west-central portion of the state within the Ouachita Mountains. These land developments include Cherokee Village, Horseshoe Bend (Izard County), and Ozark Acres (Sharp County) near Hardy; Briarcliff-by-the-Lake south of Mountain Home (Baxter County); Diamond Acres and Gaither Mountain Estates near Harrison (Boone County); Ozarks Wildlife Estates in Newton County; Holiday Island north of Eureka Springs (Carroll County); Bella Vista Village and Lost Bridge Village near Rogers (Benton County); Fairfield Bay (Van Buren County) northwest of Heber Springs (Cleburne County), and Hot Springs Village and Diamondhead Community in Garland and Saline counties near Hot Springs (Garland County). While some of these land developments are inactive, several of the more successful land developments—such as Cherokee Village, Bella Vista, Hot Springs Village, and Fairfield Bay—currently host relatively large seasonal and permanent populations, offer a wide variety of recreational and retirement opportunities, and have become an important part of the local economy.

Cooper Communities was in its infancy when founder John A. Cooper created Cherokee Village in 1954. The development site is located in the foothills of the Ozark Mountains west of U.S. Highway 62 in Sharp and Fulton counties. John Cooper marketed his property using direct mail to contact a widely scattered clientele in several Midwestern states. Within only a few years, he had sold enough lots and generated sufficient income to expand the development. It now includes more than 15,000 acres of land, seven lakes, a town hall, a shopping center, two eighteen-hole golf courses, six swimming pools, a private beach, tennis courts, nature trails, and other outdoor activities. Cherokee Village is fairly representative of the average amenity-based subdivision. On the one hand, it provides vacation and retirement home sites, numerous recreational opportunities and an active lifestyle for its residents and visitors, affordable housing opportunities, and a relatively low crime rate. On the other hand, the development also entails environmental degradation associated with the installation of a dense network of roads across steeply sloping terrain, a high concentration of septic systems, and difficulties associated with the distribution of basic services, such as central water and sewer services and police and fire protection to more than 3,000 permanent residents within a subdivision that sprawls across 15,000 acres within two counties.

Cooper Communities, with its headquarters in Rogers, has created several other significant land developments including Bella Vista and Hot Springs Village in Arkansas; Tellico Village in eastern Tennessee; Stonebridge Village in Branson, Missouri; Escapes to the Tropical Breeze in Panama City, Florida; and Escapes of Galveston, Texas. This large company employs approximately 600 people in land developments across eight states and has attracted more than 125,000 owner families to its planned communities and resorts.

Bella Vista, the second large land development created by Cooper Communities, began in 1965 on 16,000 acres of scenic real estate in Benton County. The planned recreational and retirement community, which grew to 36,000 acres, is located on U.S. Route 71 near the Missouri state line. Amenities include seven golf courses, seven lakes, tennis courts, a marina, a club house, walking trails, and many other outdoor activities. Bella Vista’s Property Owners Association continues its active role even after Bella Vista incorporated as a first-class city in November 2006. It collects dues and operates and maintains the amenities and much of the infrastructure within this sprawling subdivision. As is evident by its population growth, Bella Vista has become an attractive community for widely varying age groups. When the development began, the property owners were primarily affluent retirees. More recently, however, the demographics have changed. Younger couples and families are discovering that Bella Vista offers affordable housing and an active lifestyle all within a relatively short commuting distance to jobs in Rogers and Bentonville (Benton County). While its total population in 2000 was only 16,582, estimates as of 2010 by the Property Owners Association indicate a population of approximately 26,000.

Equally impressive is Cooper Communities’ Hot Springs Village, which began in 1970. It is nestled in the foothills of the Ouachita Mountains on 26,000 acres of land north of Hot Springs. With 34,044 property owners and a year-round population of 13,826, it is one of the largest gated communities in the United States; access is available only through security gates. More than 7,500 homes have been built, eighty-six percent of which are single-family dwellings, while fourteen percent are townhouses and timeshare units. Mobile homes are not allowed. Hot Springs Village is governed by the HSV Property Owners Association (POA), a private, tax-exempt home owners’ association. The roads, amenities, and water and sewer system are owned and maintained by the POA. The creation of a POA is a common practice employed by developers to shift the responsibility of facilities maintenance and management to the property owners. Funding for the POA is by monthly property owner assessment fees and nominal fees for the use of most of the facilities such as golf courses and tennis courts.

Fairfield Bay was one of twenty-three planned recreational communities owned by Fairfield Communities, Inc., a company that had landholdings in ten states. Fairfield Bay is used as a case study to illustrate some of the more significant positive and negative impacts of recreational and retirement communities. After rapid growth during the 1980s, Fairfield Communities began to experience financial difficulties and filed for bankruptcy in October 1990. The company emerged from bankruptcy two years later and continued to operate its resort properties until it sold all of its assets to Wyndham Vacation Resorts in the early twenty-first century. Wyndham has a global network of properties ranging from individual hotels to recreational and retirement communities.

Fairfield Bay, Fairfield Communities’ first land development project, began in 1966 along the north shoreline of Greers Ferry Lake in Arkansas on a 4,300-acre tract of land. Subsequently, the development increased in size to more than 14,000 acres in Van Buren and Cleburne counties. Initially, the developers provided little in the way of services; a sales office and a network of roads were the first changes made to this little-disturbed portion of rural Van Buren County. After numerous amenities were added, Fairfield Bay, now referred to as Wyndham Resort at Fairfield Bay, became one of the region’s most popular destinations. The resort, in addition to its beautiful natural setting, offers two top-flight golf courses, sailing, a tennis and fitness center, a shopping district, a full-service marina, horseback riding, hiking trails, and many other outdoor activities. The “Bay” is located along Arkansas Highway 16, east of Clinton (Van Buren County).

When a land development such as Fairfield Bay becomes a new community with a sizable permanent and seasonal population, it has a significant impact on the local economy. One of the most important economic benefits of recreational subdivisions is the increased tax revenues as land increases in value. Prior to the development of Fairfield Bay, rural land in Van Buren County was selling for only $50 to $100 per acre. The small one-quarter- to one-third-acre lots that were created within Fairfield Bay were sold at highly inflated prices. Lake-front and golf course lots sold for from $20,000 to $30,000, while more remote and less desirable lots frequently sold for from $5,000 to $6,000. As a result, the county has received millions of dollars in revenues that it would not have received if the project did not exist. In 2008, for example, the county received slightly more than $1.3 million in taxes from property owners at Fairfield Bay.

Another important impact is on employment. Fairfield Bay provides employment for people who do construction work, work in administrative offices, and perform many other jobs required to maintain the community. As these employees spend most of their salaries locally, additional jobs are created in trade and service establishments, which then purchase supplies from other businesses. This multiplier effect increases the economic impact of the development on both the county and the state. Since Fairfield Bay moved beyond the raw land sales stage, the nature of its employment structure has shifted from the sale of raw land to lot resale and management of existing facilities.

Unfortunately, there is also a significant negative impact. An important part of Fairfield Bay’s appeal is its location in one of the most beautiful locations in the entire Ozark region. This scenic landscape has several important environmental limitations, including steep slopes and thin mountain soil. One significant environmental problem is created by the 200 miles of unpaved roads that have been superimposed on steep slopes. Many of the roads, constructed years or even decades before they will be needed by lot owners, were used to show prospective customers the small lots that were for sale. Although some of the roads follow the natural contour, some have slopes exceeding fifteen percent and may always remain unpaved. The heavy rainfall common to the area easily washes out these roads and dumps sediment into Greers Ferry Lake and nearby streams. In addition, the roads themselves reduce the scenic beauty of the terrain, particularly where cut-and-fill is used.

Fairfield Bay is, in many respects, similar to a suburban subdivision, except its standards are not as high. For example, septic systems and individual wells are widely accepted among recreational developers. A high concentration of small lots with septic systems, particularly where aquifers are near the surface, may have a devastating impact on water quality and groundwater supplies. While developers continue to extend services outward from the core of the project, water and sewer lines are available only along a limited number of roads. Property owners wishing to build a home on their lot before services are provided must drill a well, install a septic system, and make arrangements to have electric lines extended to the property. Some homes are as far as three or four miles from areas where basic service facilities are available. Property owners could be stuck with inadequate services for years, especially those with lots located several miles from the core area.

The most significant consumer problems that are common throughout the industry include unauthorized promises made by lot sales personnel during high-pressure promotional tours, installment contract terms that are unfair to the buyer, inadequate basic services, and poor resale performance. Lot owners receive a warranty deed to their property after the lot is paid for in full. The greatest consumer-related problem is the promise of profits from the resale of lots, because it is unlikely that lots purchased at highly inflated prices will resell at a profit. Resale may be especially difficult if the developer still has unsold lots on hand.

While there are many recreational and retirement communities that are well planned, implemented to conform to the environmental limitations of the areas in which they are located, and designed to operate using sound land use practices, many are not. There are numerous poorly planned, substandard subdivisions whose developers have shown no concern for the environment and have made no attempts to use sound land-use practices. Problems associated with such subdivisions are abundant and widespread. The blame for these problems does not rest entirely with the developer, however. Governmental officials, whose responsibility it is to regulate the use of land resources, as well as the public at large who help to establish public policy and who purchase this property, must share some of the responsibility for the negative impact. These problems and many others point to the need for planning, regulatory controls, or alternatives for developmental operations to prevent the indiscriminate disruption of a region without first considering future ramifications or alternatives. One of the most basic and important steps to resolving problems is to require development to occur in relatively small and controlled phases. This approach would require developers to provide basic services to existing lots before expanding to other areas. In Florida, for example, this approach is referred to as concurrency. This means that basic services must be provided (already available) before or when the lots are sold.

Obviously, recreational and retirement communities have had and are continuing to have a tremendous impact on the areas in which they are located. Whether or not the positive features outweigh the negative impact is difficult to determine. Clearly, the more extensive projects have become dominant features of landscapes that once were sparsely populated rural environments. Ironically, while properties within these subdivisions are often promoted as places where individuals and families can “get away from it all,” the housing densities often become higher than those found in many urban settings as lots become owner occupied. These and other unanticipated problems are characteristic of the recreational and retirement land development industry. Whether or not the projects meet the needs of their residents all too often is dependent upon long-term decisions made by corporate officials. Some developers operate under the guise of creating “new communities” but are only interested in generating income from sales of lots. Others are much more legitimate and follow through with commitments to create viable recreational and retirement communities. Even these efforts are not without problems, but at least property owners are not stuck with a worthless parcel of land in an obsolete or abandoned subdivision. Such unsuccessful projects contrast sharply with the situation at Hot Springs Village and the other more viable land developments in Arkansas that have become recreational and retirement meccas for thousands of people and dominant features of what were once virtually uninhabited and little disturbed landscapes within the Natural State.

For additional information:

Fite, Gilbert C. From Vision to Reality: A History of Bella Vista Village, 1915–1993. Rogers, AR: RoArk Printing, Inc., 1993.

Miller, Wayne P. “Economic and Fiscal Impact of Hot Springs Village.” Little Rock: University of Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service, 2005.

Morgenson, Gretchen. “Suckering the City Bumpkins.” Forbes, December 26, 1988, pp. 39–40.

Paulson, Morton C. The Great Land Hustle. Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1972.

Self, Jason. “The Environmental Impact of Amenity-Based Subdivisions: A Case Study of Cherokee Village.” PhD diss., Arkansas State University, 2008.

Stroud, Hubert B. The Promise of Paradise: Recreational and Retirement Communities in the United States since 1950. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995.

Talbot, Tish. “John A. Cooper, Sr.: A Vision of the Future.” Arkansas Times, March 1983, pp. 30–33, 36–40.

Hubert B. Stroud

Arkansas State University

Bella Vista

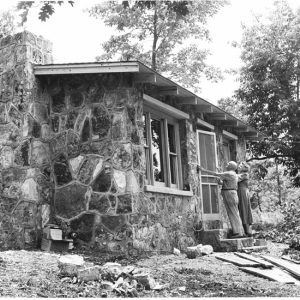

Bella Vista  Native Stone House

Native Stone House

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.