calsfoundation@cals.org

Nelson Hackett (1810?–?)

Nelson Hackett was an Arkansas slave whose 1841 escape to Canada (then a colony of Great Britain) led to a campaign by his owner to have him extradited to the United States on charges of theft as a way of getting around the legal sanctuary that Canada provided to fugitive slaves. Hackett’s extradition aroused the ire of abolitionists on both sides of the border and ultimately resulted in a limitation of the 1842 Webster-Ashburton Treaty’s extradition provision.

Nelson Hackett enters the historical record in June 1840 when he was acquired by Alfred Wallace, a wealthy Washington County plantation owner, storekeeper, and land speculator. Hackett was described as “a Negro dandy” of about thirty years of age. Slaves in the Arkansas uplands did a wider variety of labors than did their lowland counterparts; they grew cotton but also were used for loading boats and in various public works projects.

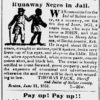

Hackett served as Wallace’s valet and butler and escaped from his owner while Wallace was visiting central Arkansas in mid-July 1841. He set out for Canada, taking with him Wallace’s fastest horse, as well as a gold watch, a coat, and a saddle. Six weeks after his escape, he crossed into Canada and soon reached the southwestern Ontario town of Sandwich.

Shortly after Hackett’s escape, Wallace set out in pursuit of him, along with his associate George C. Grigg, and he soon learned of Hackett’s destination. Following Hackett to Upper Canada, Wallace gave depositions against the escaped slave for theft and succeeded in having him arrested near Chatham and jailed at Sandwich. Originally, Hackett confessed to the crimes but later claimed that he had been beaten during his interrogation.

In mid-September, Wallace and Grigg traveled to Michigan to begin extradition proceedings against Hackett, and Michigan’s acting governor, J. Wright Gordon, issued a formal request to the Canadian government for Hackett’s surrender to U.S. authorities. However, William Henry Draper, attorney general for Upper Canada, refused, noting that the state of original jurisdiction, Arkansas, had not made the request. Therefore, Wallace and Grigg returned to Arkansas, initiating criminal charges in Fayetteville (Washington County). On November 26, 1841, a grand jury indicted Hackett for grand larceny, and Governor Archibald Yell, to whom Wallace was well connected, made a formal request to Canadian authorities for Hackett’s extradition four days later. In a petition, Hackett begged to be allowed to remain in Canada, stating that in Arkansas he would be “tortured in a manner that to hang him at once would be a mercy.” However, in mid-January 1842, Sir Charles Bagot, governor general of Canada, ordered that Hackett be extradited.

On the night of February 7, 1842, Hackett was bound and gagged and secretly spirited across the border. He was brought to a Detroit jail, where he spent two months in solitary confinement while his captors waited for winter’s passing to allow for further travel. Detroit abolitionists initially hoped to use his case in their campaign against slavery, but Hackett’s ostensible theft of Wallace’s property complicated the matter.

In the spring, Onesimus Evans and Lewis Davenport, who were responsible for transporting Hackett back to Arkansas, conveyed the fugitive to Chicago and caught a stagecoach to Peoria, Illinois. On May 21, 1842, during an overnight stop in Princeton, Illinois, Hackett escaped once more. He was captured two days later by a farmer from whom he had sought food. On May 26, he was temporarily kept in a Missouri jail, and by the next month, he was back in Fayetteville.

Hackett’s case provoked a public furor in Canada, which had long been a haven for those who had fled slavery in the United States, and many abolitionists worried that the case set a precedent by which the American slaveocracy would seek the return of their human property by means of extradition requests. Indeed, the Canadian Western Herald reported that the legal and other fees incurred by Wallace came to some $1,500, far more than Hackett’s market value, and that Wallace’s motive was to “deter other slaves from running away” to Canada. The return of Hackett to his owner also went counter to Canadian traditions regarding fugitive slaves. Previous extradition laws did not mention escaped slaves. Likely as a consequence of the Hackett case, Article 10 of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, approved by the British and American governments on August 9, 1842, carefully limited extradition to criminals, thus protecting fugitive slaves from automatic surrender to their owners.

Little is known of Hackett’s fate. He was never actually tried on the charges that secured his extradition. Another slave who escaped from Wallace reported that, upon Hackett’s return to Fayetteville, he was bound and flogged several times, the first time in front of all the slaves. Hackett was then sold to someone in the Texas interior. Abolitionist societies in Britain attempting to purchase and free him could find no trace of him after this transaction.

For additional information:

Abbott-Namphy, Elizabeth. “Hackett, Nelson.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography. http://www.biographi.ca/EN/ShowBio.asp?BioId=37541 (accessed January 25, 2023).

Nelson Hackett Project. University of Arkansas. https://nelsonhackettproject.uark.edu/ (accessed January 25, 2023).

Pierce, Michael. “‘Adventures. Escape of a Slave.’: An Account of the Flight of Nelson Hackett, May 27, 1842.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 79 (Summer 2020): 133–141.

Ryburn, Stacy. “Fayetteville Marker to Share Story of Slave’s Quest for Freedom.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, March 27, 2022, pp. 1B, 6B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/mar/27/marker-to-tell-story-of-enslaved-man-who-fled/ (accessed January 25, 2023).

———. “Fayetteville Looks at Renaming Street.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 4, 2022, p. 3B. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/sep/04/yell-to-hackett-proposal-would-change-street-name/ (accessed January 25, 2023).

Zorn, Roman J. “An Arkansas Fugitive Slave Incident and Its International Repercussions.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 16 (Summer 1957): 139–149.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood, 1803 through 1860 Slave Resistance

Slave Resistance

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.